4 years (3). It is uncommon in the first 6 months of life and after 6 years of age. It is slightly more common in girls than in boys (3). It is bilateral in about 5% of cases (4). Wilms tumor may be associated with hemihypertrophy and aniridia and with genital anomalies, such as cryptorchidism and hypospadias (5). Patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Denys-Drash syndrome have an increased risk of developing Wilms tumor (5,6). Wiedemann-Beckwith syndrome is related to abnormalities on chromosome 11p15 and characterized by multiple craniofacial anomalies, abdominal wall defects, and tumors of the genitourinary tract, liver, adrenal gland, and central nervous system among other abnormalities. Denys-Drash syndrome, due to mutations of the WT1 gene, is also associated with a congenital nephropathy and disorders of sexual development. Wilms tumor is rare in adults (3). Wilms tumor is believed to arise from embryonic tissues called nephrogenic rests that fail to undergo normal involution (7).

TABLE 30.1 Modified 2004 WHO classification of renal tumors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

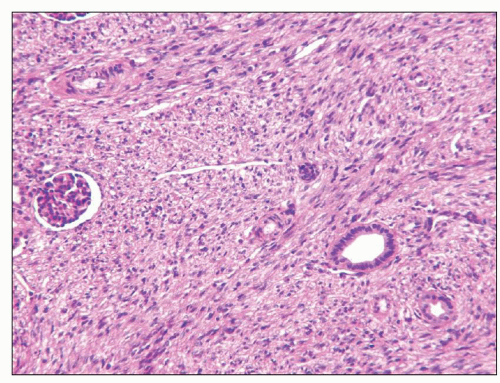

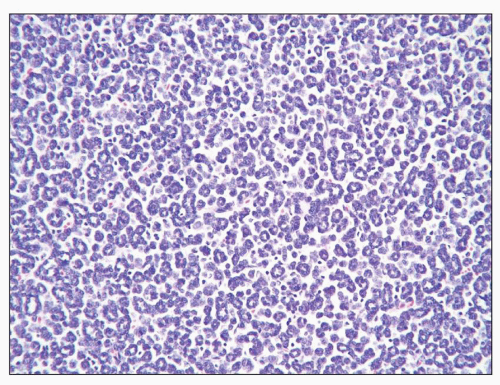

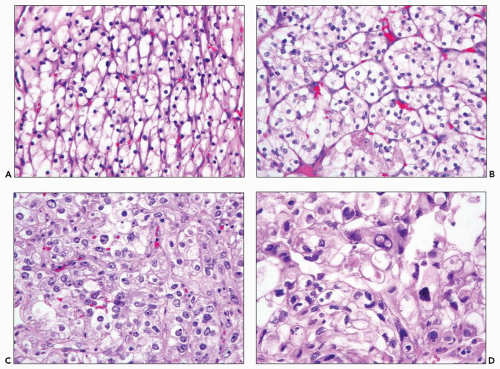

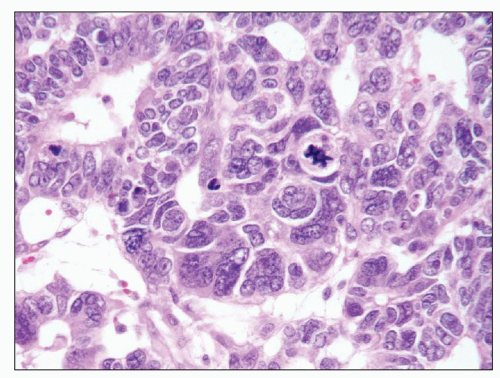

FIGURE 30.2 Wilms tumor. Typical triphasic histology with epithelial, blastemal, and mesenchymal elements. In this case, the mesenchymal component is primitive and undifferentiated. |

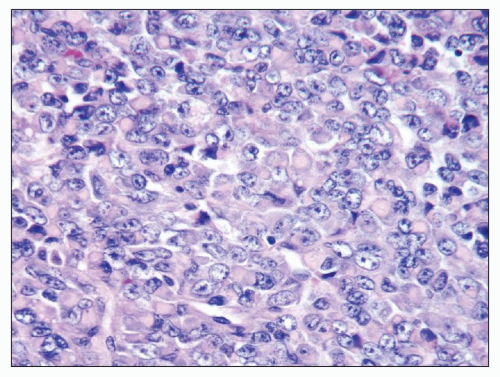

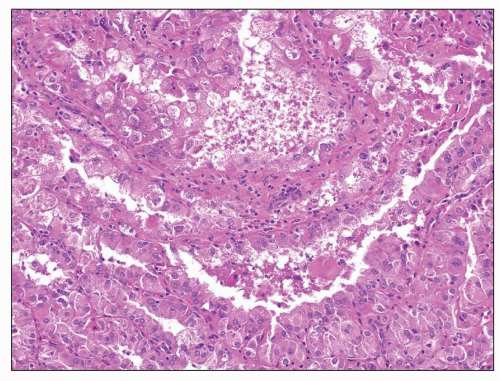

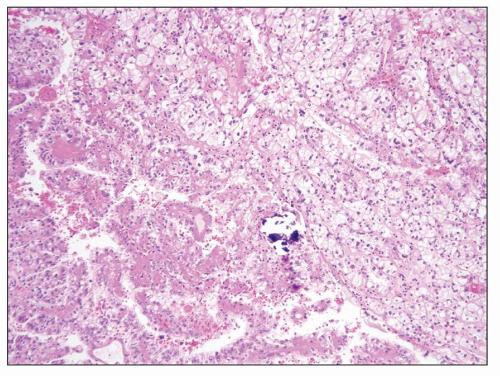

FIGURE 30.3 Wilms tumor. Focus of anaplasia in a Wilms tumor with nucleomegaly, hyperchromasia, and multipolar mitotic figure. |

an abdominal mass. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma was first recognized in 1966 (25), and subsequent studies have shown it to be a morphologically distinct tumor with a good prognosis (24).

TABLE 30.2 Staging system for renal tumors of childhood | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

spurious, and if there is definite differentiation toward skeletal muscle, the tumor is not a rhabdoid tumor. The cytoplasm commonly contains a large eosinophilic inclusion that forces the nucleus to one side. At the ultrastructural level, these inclusions are composed of whorled microfilaments (39). A variety of rare patterns have been recognized, including sclerosing, epithelioid, spindle cell, lymphomatoid, vascular, pseudopapillary, and cystic (39). These are usually mixed with the typical pattern and with each other and retain the characteristic nuclear features. It is important to recognize that a number of other primary kidney tumors including medullary carcinoma and RCC can have rhabdoid-like cells (43).

that developed metastases (61,62). Fewer than a handful of metanephric adenomas have been associated with psammoma bodies or even epithelial cells in lymph nodes draining the kidney with the metanephric adenoma; the nature of this process is unclear (63).

FIGURE 30.8 Xp11.2 translocation carcinoma. The tumor is composed of clear cells forming papillary and solid architectures. Note the large calcification. |

was published (86). A few similar looking tumors have also been reported in children treated with chemotherapy for other tumors (87).

tumor of cortical epithelium and consider all lesions composed of clear cells to be malignant regardless of size (1,10).

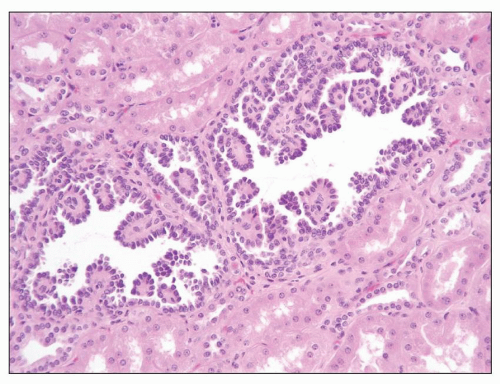

FIGURE 30.10 Papillary adenoma. A small papillary lesion merges imperceptibly with adjacent normal tubules; the cells have small uniform nuclei without significant atypia. |

Cysts may be associated with hemorrhage. Necrosis is absent. Nuclei are regular and round to oval, with granular chromatin and central nucleoli. The presence of cells with bizarre pleomorphic nuclei is well recognized and believed to be degenerative (Fig. 30.13). Mitotic figures are absent or rare, at most. Evidence suggests that oncocytoma originates from the intercalated cell of the collecting duct (123,124). Distinguishing oncocytoma from chromophobe RCC is important because the latter may show malignant behavior.

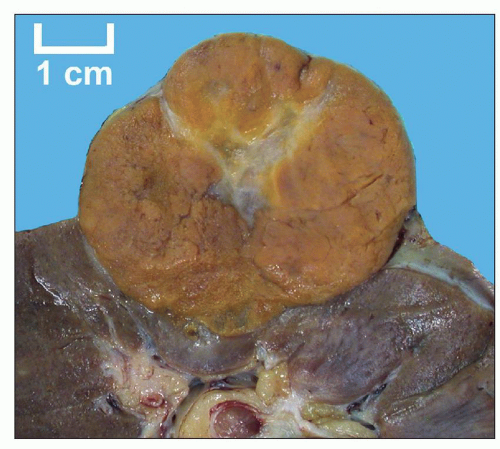

FIGURE 30.11 Oncocytoma. The tumor is well circumscribed and solid with a golden brown color and central patch of edematous stroma. |

in the relevant sections below. The classic triad of presenting symptoms consists of hematuria, pain, and flank mass, a combination that is generally associated with advanced stage (135). However, approximately 40% of patients lack all of these and present with systemic symptoms. A common constellation is weight loss, abdominal pain, and anorexia, which may suggest carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract (135). In up to 21% of patients, there is fever without infection (136,137). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is elevated in approximately 50% of cases (138). Although blood erythropoietin levels are elevated in almost two thirds of patients (139,140), erythrocytosis occurs in less than 2% (140). Hypochromic anemia unrelated to hematuria occurs in about one third of cases (137). Systemic amyloidosis occurs in about 3% to 8% of patients with RCC and is of the AA type (141).

TABLE 30.3 Hereditary renal cell carcinoma syndromes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 30.4 Fuhrman nuclear grading system | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

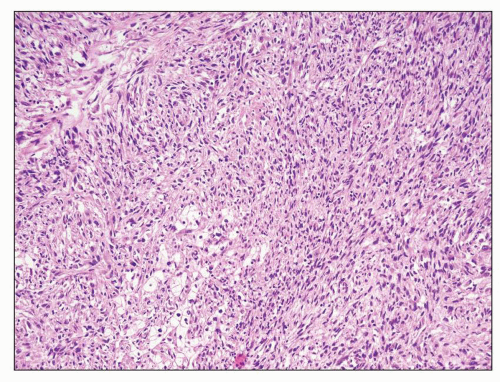

the types of RCC. Microscopically, these resemble fibrosarcoma or undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma (Fig. 30.16) (188). Heterologous differentiation toward osteogenic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or rhabdomyosarcoma is uncommon occurring in only 1% to 2% of cases (186,188,189,190). Patients with even small foci of sarcomatoid carcinoma have a much worse prognosis than those whose tumors do not have such foci (186,188), so thorough sampling of areas with differing gross appearances (especially firm, whitish areas) is important in evaluating RCC.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree