Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitis

Vasculitis is vessel wall inflammation. Perivascular leukocyte infiltration alone is not vasculitis. Diapedesis of leukocytes through the walls of vessels, usually postcapillary venules, that does not cause pathologic vessel wall injury is not vasculitis. The chronic phase of vasculitis may be characterized by sclerosis without inflammation; thus, in this instance, a diagnosis of vasculitis is made based on evidence indicating that the sclerosis was preceded by inflammation. Nonspecific chronic inflammation with infiltration by predominantly lymphocytes in the setting of arteriosclerosis should not be considered vasculitis.

Vasculitis can affect any type of vessel in any organ and thus results in a broad range of clinical signs and symptoms. Because the kidneys have numerous and diverse vessels, they are a frequent target for many types of vasculitis, especially those that affect predominantly small vessels such as capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries. The medullary vasa recta can be affected by small-vessel vasculitides. Renal veins are rarely if ever involved directly by noninfectious vasculitides.

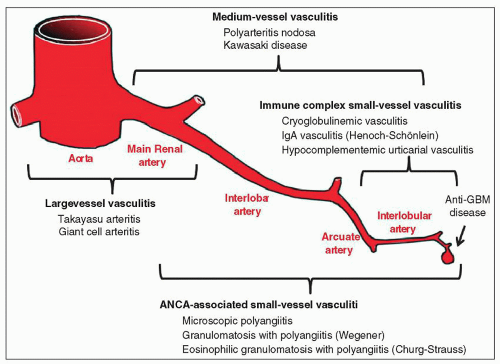

No approach to classifying vasculitides is universally accepted. Different names have been used for the same type of vasculitis, and specific types of vasculitis have been given multiple names. The approach used in this chapter is the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature System (

Table 17.1;

Fig. 17.1) (

1), which is a modification of the 1994 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature System (

2) that was used in the previous edition of this book. Three major categories of vasculitis are large-vessel vasculitis, medium-vessel vasculitis, and small-vessel vasculitis. Although these names imply that the size of the vessels affected by inflammation is the major basis for categorizing vasculitides, this is a gross oversimplification because many factors must be taken into consideration to classify a vasculitis precisely, including the type of vessel involved, the pattern of inflammatory injury, distribution of organ involvement, immunopathologic findings in the tissue and blood, and clinical features. As demonstrated in

Figure 17.1, substantial overlap exists among categories with respect to the size of involved vessels. Therefore, diagnostic categorization requires a relatively complex integration of not only pathologic data but also immunologic and clinical data to reach the most appropriate diagnosis.

In the kidney, small-vessel vasculitides, such as IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura), cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease,

microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (Wegener granulomatosis), most often affect glomerular capillaries and thus cause glomerulonephritis (

1,

3,

4). Renal involvement by small-vessel vasculitis usually manifests as nephritis with hematuria, proteinuria, and renal insufficiency. Different small-vessel vasculitides have different frequencies of arterial involvement; for example, IgA vasculitis and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis rarely affect intrarenal arteries, whereas MPA and GPA more often affect intrarenal arteries although this may not be sampled in a renal biopsy specimen. The interlobular arteries are the arteries most often affected by small-vessel vasculitis. The small-vessel vasculitides are discussed in detail in several other chapters in this book, including Chapter 16 (antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies [ANCA] small-vessel vasculitis), Chapter 12 (IgA vasculitis), and Chapter 22 (cryoglobulinemic vasculitis), and thus are mentioned in this chapter only in the context of the nomenclature and differential diagnosis of medium- and large-vessel vasculitis.

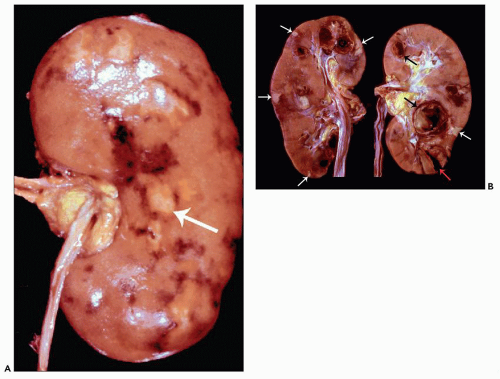

Medium-vessel vasculitis, such as polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and Kawasaki disease (KD), may affect any of the renal arteries but most often involves the interlobar and arcuate arteries (

2). Clinically significant renal involvement is more common with PAN than with KD; however, postmortem examinations reveal that both PAN (

5) and KD (

6) often affect the kidneys. PAN and KD are forms of necrotizing arteritis characterized by segmental transmural necrosis, often with aneurysm formation. This necrosis may result in rupture and hemorrhage, although partial or complete occlusion with resultant ischemia is more common and may cause infarction. The narrowing or obliteration of lumina is caused by various combinations of inflammation, thrombosis, and sclerosis. Renal involvement by medium-vessel vasculitides often causes abdominal pain from visceral inflammation and ischemia. Renal rupture with hemorrhage into the retroperitoneum or peritoneal space is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication. Hematuria (resulting from renal infarction and hemorrhage from inflamed arteries rather than glomerulonephritis) is a frequent consequence of renal involvement by medium-vessel vasculitis, but renal insufficiency and substantial proteinuria are less frequent than in the small-vessel vasculitides.

In literature prior to the 1990s, polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) was not uniformly separated from microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) (formerly called microscopic polyarteritis or microscopic periarteritis) (

2). In the Chapel Hill Nomenclature System approach to classification used in this book, the presence or absence of glomerulonephritis is a major distinguishing feature between PAN and MPA (

1,

2). According to this classification system, PAN affects only arteries and thus does not cause glomerulonephritis, whereas MPA has a predilection for vessels other than arteries (especially venules and capillaries) and frequently causes necrotizing glomerulonephritis. This approach of separating PAN from MPA is supported by the strong association of ANCA with MPA but not PAN (

7).

Large-vessel vasculitides, such as giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis, affect predominantly the main renal artery or its aortic ostium, although they also may involve intraparenchymal renal arteries (

8,

9). These chronic inflammatory and sclerosing vascular diseases often cause narrowing of arterial lumens with distal ischemia, but alternating segments with stenosis and dilation may occur. Pathologic involvement of renal vessels may be clinically silent or cause renovascular hypertension, especially in patients with Takayasu arteritis (

10). Before discussing in detail the pathologic features of vasculitides in the kidneys, some of the historical background that underlies our understanding of the pathology and classification of vasculitides is reviewed.

Historical Background of Necrotizing Arteritis

Most medium-vessel vasculitides and small-vessel vasculitides have extensive vascular necrosis during the acute phase, a finding that differs from the more indolent and granulomatous inflammation of the large-vessel vasculitides. In other words, the initial arterial involvement by small- and medium-vessel vasculitides is a necrotizing arteritis and that of the large-vessel vasculitides is a chronic granulomatous inflammation (

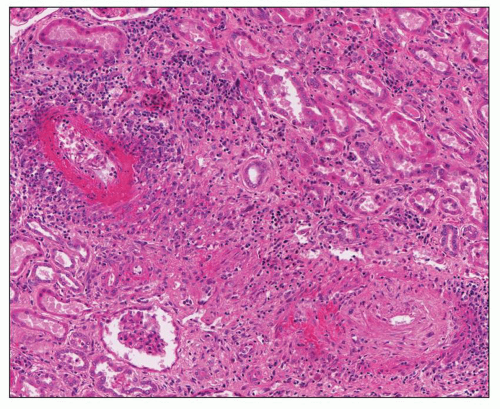

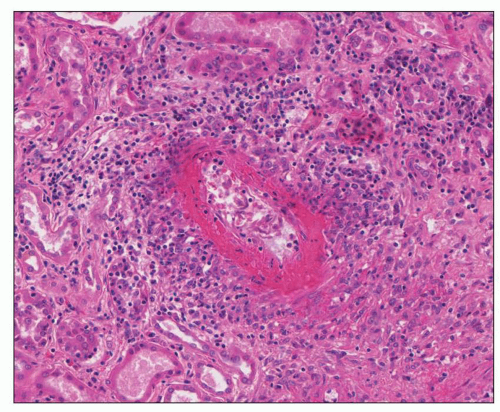

11). Unlike the large-vessel vasculitides, which rarely affect vessels within the kidney parenchyma that are sampled in renal biopsy specimens, the medium-vessel vasculitides and especially the small-vessel vasculitides often involve the kidney parenchyma, with the latter frequently causing significant renal dysfunction. The necrotizing vascular inflammation is characterized by segmental fibrinoid necrosis with neutrophilic infiltration (

11,

12). The neutrophils rapidly undergo apoptosis and necrosis with nuclear fragmentation (leukocytoclasia). This light microscopic lesion is similar in arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins (

12). By definition, a major distinction between the medium-vessel vasculitides and the small-vessel vasculitides is that the former involve only arteries, whereas the latter may involve arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and venules (

1,

2). Thus, in a patient with systemic vasculitis, the presence of glomerulonephritis is diagnostic for some form of small-vessel vasculitis.

Both infectious and noninfectious vasculitides cause acute necrotizing inflammation of vessels. Infectious vasculitis may affect any type of vessel, although particular infections have a predilection for certain types of vessels. Direct infection of vessel walls, for example, by

Rickettsia or

Neisseria, incites inflammation. Infections also can cause vasculitis by generating pathogenic immune complexes, for example, mixed cryoglobulin immune complexes induced by hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and resulting in cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (discussed in detail in Chapter 22). Infectious vasculitis caused by direct invasion of vessel walls is not discussed in this chapter. Noninfectious necrotizing inflammation of arteries was first recognized in the context of PAN (

13), whereas noninfectious necrotizing inflammation of vessels smaller than arteries (i.e., arterioles, capillaries, and venules) was first appreciated in patients with purpura (

14).

The initial recognition of necrotizing arteritis began with the gross observance of nodular aneurysmal lesions in arteries. Rokitansky (

15) gave one of the first gross descriptions of systemic necrotizing arteritis in a report on arterial aneurysms in 1852; however, Kussmaul, who was a clinician who studied pathology under Rokitansky and Virchow, and the pathologist Maier published the first definitive report in 1866 (

13). Their patient had fever, anorexia, muscle weakness, myalgias, paresthesias, abdominal pain, and oliguria. He died, and an autopsy revealed nodular inflammatory lesions in medium-sized and small arteries throughout the body. These authors observed white-yellow nodular arterial lesions in the kidneys that were most conspicuous at the corticomedullary junction. They also noted the presence of infarcts. Thus, their patient had features very similar to those in

Figure 17.2. Kussmaul and Maier (

13) named the disease

periarteritis nodosa to emphasize what they

perceived as predominantly perivascular inflammation that produced focal nodular vascular lesions.

In 1903, Ferrari (

16) introduced the term

polyarteritis to emphasize the involvement of multiple arteries and to do away with the misleading term

periarteritis because he recognized the transmural character of the disease and illustrated this beautifully with color drawings in his publication. This term was advocated further by Dickson in 1908 (

17), who also noted the frequency of renal involvement by arteritis resulting in thrombosis and infarction. Currently, the name

polyarteritis nodosa is generally used, rather than

periarteritis nodosa (

1).

Until distinctive subcategories of necrotizing arteritis were recognized, PAN became a wastebasket diagnostic category. In essence, any patient with necrotizing arteritis was said to have PAN, although many of these patients had different clinical and pathologic features (

18,

19,

20,

21). Unfortunately, for many years after the recognition of pathologically and clinically distinct subcategories of necrotizing arteritis, some pathologists continued to lump different variants of necrotizing arteritis under the term PAN. Many studies, however, have clearly demonstrated that histologically identical necrotizing arteritis occurs as a component of many clinically, pathologically, and pathogenetically distinct types of vasculitis, some of which have concurrent vasculitis in vessels smaller than arteries (i.e., the small-vessel vasculitides) (

1). The natural history, prognosis, and most appropriate treatment differ among these categories of necrotizing vasculitis. Thus, their recognition is not merely an academic exercise, but rather has major implications for prognosis and treatment.

By the 1920s, a variant of systemic necrotizing vasculitis with arteritis as well as inflammation of small vessels including small arteries, arterioles, venules, and capillaries was recognized (

20,

21). One of the earliest pathologic features found to distinguish among clinically distinctive categories of necrotizing vasculitis was glomerulonephritis. In 1930, Arkin (

5) published one of the best early pathologic descriptions of systemic necrotizing arteritis and observed two basic forms, one with a predominance of grossly visible vascular nodules and a second “microscopic form” in which the vasculitis could be identified only with the aid of microscopy. Arkin pointed out that the kidneys were a major target organ for both the gross and microscopic forms of arteritis. In a 1948 publication, Davson et al. (

22) focused on renal involvement in patients with necrotizing arteritis and concluded that an important feature that divided the microscopic form of arteritis from the form with conspicuous grossly identifiable arterial nodules was the presence in the former but not the latter of extensive necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Also in 1948, Zeek et al. (

23) published similar observations. These investigators noted that one group of patients had extensive necrotizing arteritis with grossly discernible nodules and no glomerulonephritis, whereas another group had

microscopic arteritis that was accompanied by necrotizing glomerulonephritis. They considered the former to be true PAN, and they called the latter

hypersensitivity angiitis because they thought it could be caused by an allergic response possibly to a drug (

23,

24). The term

hypersensitivity angiitis has subsequently been used for many different patterns of vasculitis, including relatively nonspecific cutaneous manifestations of drug hypersensitivity. As a consequence, this name has little diagnostic utility and probably should be abandoned as a diagnostic term.

Thus, by the 1940s, strong evidence indicated that patients with necrotizing arteritis could be divided into two major categories: those with systemic necrotizing arteritis with conspicuous gross nodular inflammatory arterial lesions but no glomerulonephritis and those predominant involvement of small arteries as well as involvement of vessels smaller than arteries, such as glomerular capillaries. This latter category was variable called

microscopic polyarteritis,

microscopic periarteritis, or

hypersensitivity angiitis. In an analysis of 38 autopsy cases with necrotizing arteritis, Heptinstall (

25) confirmed the usefulness of the presence or absence of glomerulonephritis as a criterion for separating PAN from microscopic polyarteritis. Using clinical, renal biopsy, serologic, and angiographic data, Guillevin et al. (

7,

26) have demonstrated that this distinction between PAN and MPA not only is possible and appropriate but also is of major value in guiding patient management.

While microscopic polyarteritis was emerging as a discrete diagnosis, two other variants of vasculitis were separated from PAN: Wegener granulomatosis and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Although these diseases frequently have vasculitis in vessels other than arteries, both had initially been included in the PAN category because patients often had necrotizing arterial lesions that were histologically identical to those in patients with PAN. Klinger (

27) initially reported granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) in 1931 as a “borderline type of periarteritis nodosa.” This disease subsequently was described in more detail by his former schoolmate Wegener (

28), which prompted widespread adoption of the term Wegener granulomatosis until this term was replaced by granulomatosis with polyangiitis (

29). In a landmark publication, Godman and Churg (

19) published the definitive description of GPA in 1954. They recognized the following triad of features: necrotizing “angiitis,” necrotizing inflammation of the respiratory tract, and necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Subsequently, patients with limited expressions of GPA were recognized who did not manifest all the features, such as patients with no glomerulonephritis (

30).

Another variant of necrotizing vasculitis was reported by Churg and Strauss in 1951 (

18). In this same article, the authors also pointed out that what was called

periarteritis nodosa was a heterogeneous group of vasculitides. They described 13 patients with asthma, eosinophilia, granulomatous inflammation, necrotizing vasculitis (including necrotizing arteritis), and focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis. They noted that similar patients had previously been reported as having PAN occurring in patients with asthma. This distinct variant of necrotizing vasculitis has been called Churg-Strauss syndrome, but the name proposed by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference is eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) (

1).

In their landmark 1954 article that elucidated the features of GPA, Godman and Churg (

19) concluded that MPA, GPA, and EGPA are closely related to each other and are distinct from PAN. More recent data support this conclusion, for example, the strong association of MPA, GPA, and EGPA (when glomerulonephritis is present), but not PAN, with ANCA and the strong association of a subset of PAN with hepatitis B infection (

7,

26,

31,

32,

33,

34), but not MPA, GPA, or EGPA.

The 1994 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference proposed that the term

microscopic polyarteritis be replaced with the term

microscopic polyangiitis because many patients with this category of vasculitis have inflammation in vessels other than arteries, such as arterioles, capillaries, and venules (

1). When this approach is used, MPA is a more frequent diagnosis than is PAN, especially in patients who are seen by nephrologists and nephropathologists.

The major necrotizing arteritis in the medium-vessel vasculitis category other than PAN is Kawasaki disease (KD). The mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MCLNS), which is the hallmark of KD, was first described by Tomisaku Kawasaki in 1967 (

33) and consists of polymorphous erythematous rash, erythema of the palms and soles, indurative edema of the extremities followed by desquamation, erythema of the oropharyngeal mucosa, conjunctivitis, and nonsuppurative lymphadenopathy (

34,

35). In a study of autopsy cases, Tanaka, Naoe, and Kawasaki determined that necrotizing arteritis involving medium and small arteries is an important component of KD and may affect the kidneys, especially the interlobar arteries (

6,

36). Because KD usually occurs in children younger than 5 years of age and is associated with necrotizing arteritis, some examples have been reported under the designation

infantile PAN (

34,

37). However, KD is easily separated from PAN by the characteristic MCLNS. Necrotizing arteritis caused by PAN, as well as arteritis as a component of a small-vessel vasculitis, such as MPA, occasionally occurs in children and should not be misdiagnosed as KD.

In summary, evaluation of patients with necrotizing arteritis has revealed multiple clinically and pathologically distinctive entities, some that affect predominantly, if not exclusively, arteries (i.e., medium-vessel vasculitides) and others that affect not only arteries but also vessels smaller than arteries (i.e., small-vessel vasculitides). In fact, many patients with small-vessel vasculitis have involvement exclusively of vessels other than arteries, for example, glomerulonephritis, pulmonary alveolar capillaritis, and cutaneous dermal venulitis.

Historical Background of Large-Vessel Vasculitis

Large-vessel vasculitides affect the aorta and its major branches more often than does small-vessel vasculitis or medium-vessel vasculitis (see

Fig. 17.1 and

Table 17.1) (

1,

38). Renal parenchymal involvement is less frequent with large-vessel vasculitis compared to medium- and small-vessel vasculitis. Nevertheless, large-vessel vasculitides can affect any type of artery in the kidney although the main renal arteries and their first- and second-order branches are affected most often. Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis are the two major categories of large-vessel vasculitis. Both cause chronic inflammation in arteries that is characterized by mononuclear leukocyte infiltration with a predominance of monocytes, macrophages, and T lymphocytes (

11,

38). Often, but not always, the inflammation has a granulomatous character with numerous macrophages, sometimes with multinucleated giant cells. Advanced disease is characterized predominantly by sclerosis rather than by inflammation, a finding that may complicate pathologic diagnosis because it can be confused clinically and pathologically with

arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis. The arterial inflammation and resultant scarring cause narrowing of lumina that, in turn, causes ischemic symptoms, for example, pulselessness, claudication, and renovascular hypertension.

A comprehensive clinical description of Takayasu arteritis was made by Savory in 1856 (

39), although patients with pulseless disease had been reported in the medical literature since the mid-eighteenth century (

40). The disease is named after Mikito Takayasu, a Japanese ophthalmologist who reported the ocular complications of this disease in 1908, even though he did not recognize the underlying vasculitic features (

41). The reduced vascular perfusion caused by the narrowing of arteries initially led to the realization that this disease affects arteries and also is the basis for another designation for this disease, “pulseless disease.”

The temporal artery involvement of GCA brought this disease to the attention of Hutchinson in 1890 (

42). Over the next 50 years, the widespread aortic and arterial distribution and the granulomatous nature of this disease became apparent (

43), and shortly thereafter, the association with polymyalgia rheumatica was recognized (

44,

45). The term

giant cell arteritis is more appropriate than

temporal arteritis for this category of vasculitis because not all patients with GCA have temporal artery involvement, and vasculitides other than GCA (e.g., PAN, MPA, GPA) can cause temporal artery inflammation (

2,

46). Glomerulonephritis is not a feature of GCA; thus, if a patient has clinical evidence of glomerulonephritis and temporal artery inflammation, the diagnosis is probably not GCA, but rather some form of small-vessel vasculitis with temporal artery involvement.

The subsequent sections of this chapter review the clinical and pathologic features of PAN, KD, Takayasu arteritis, and GCA, in this order, with an emphasis on the renal involvement. Various forms of immune complex small-vessel vasculitis are reviewed in multiple chapters, and ANCA small-vessel vasculitis is reviewed in Chapter 16.