While bacteria cause immunologic glomerular injury and glomerulonephritis, this topic is not discussed here (see Chapter 10).

TABLE 24.1 Clinical syndromes of acute pyelonephritis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

situation. There is an increased prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in older patients; in men, it is commonly caused by prostatic enlargement and loss of bactericidal activity of prostatic secretions (17). Poor bladder emptying due to uterine prolapse is considered important in women (18,19). Neuromuscular disease, increased instrumentation, and catheter use contribute in both sexes. Asymptomatic bacteriuria, or asymptomatic UTI, is defined by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force as isolation of a specified quantitative count of bacteria in an appropriately collected urine specimen obtained from a person without symptoms or signs referable to urinary infection (20). Asymptomatic bacteriuria is due to bacteria that lack virulence factors (discussed under pathogenesis).

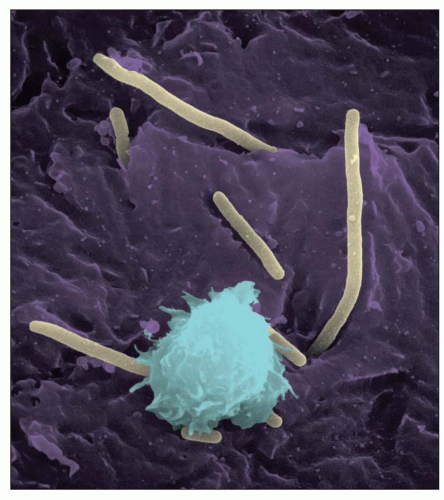

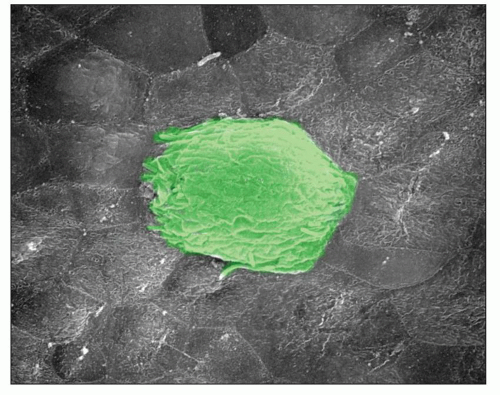

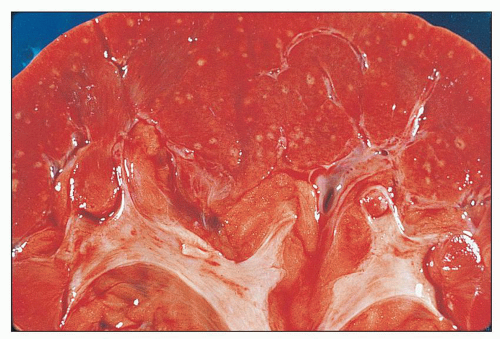

FIGURE 24.2 Acute pyelonephritis. Cortical abscesses are apparent and straight yellow streaks (thin arrows) and hyperemia in the medulla (thick arrow). |

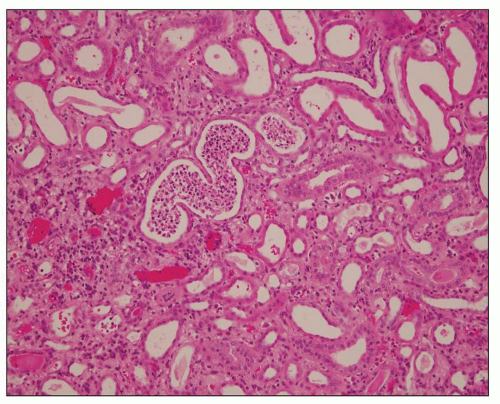

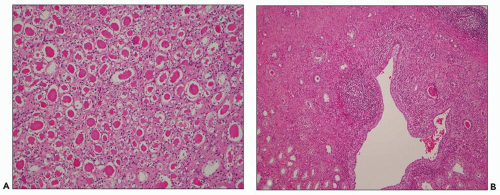

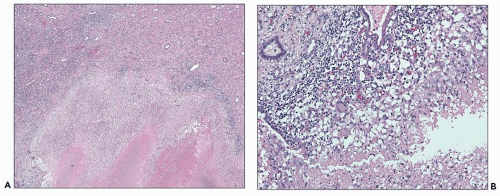

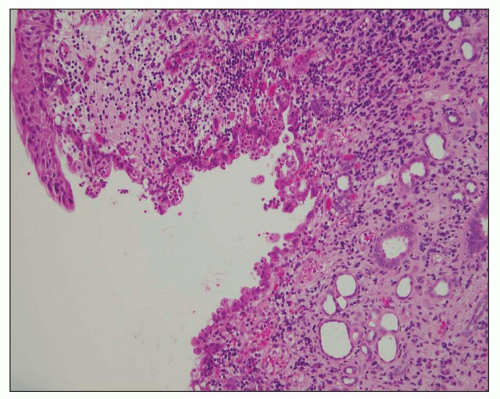

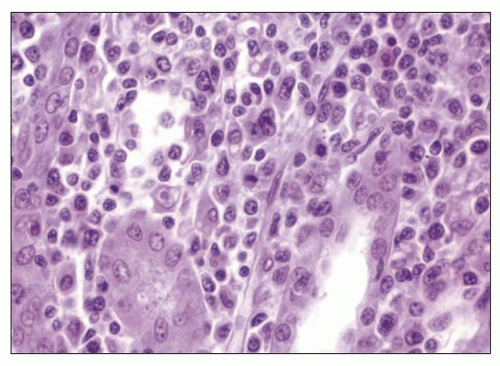

FIGURE 24.6 Acute pyelitis; neutrophils erode the lining epithelium forming microabscesses. (H&E; ×200.) |

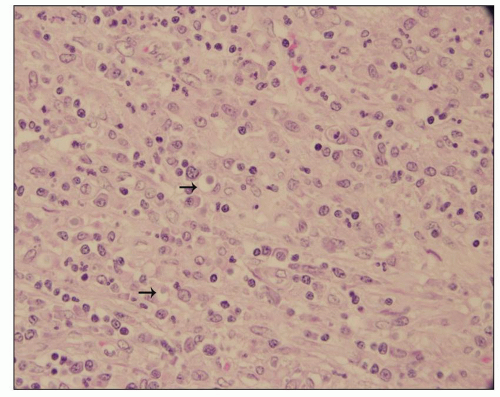

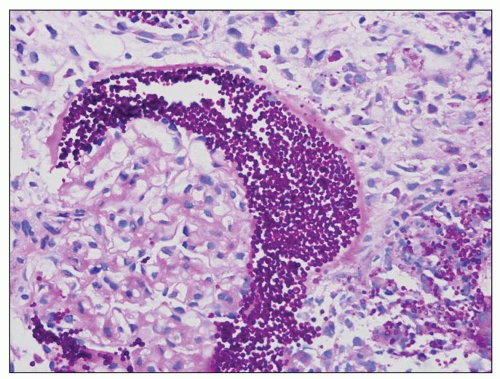

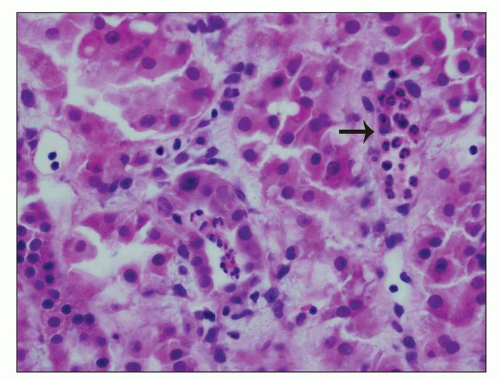

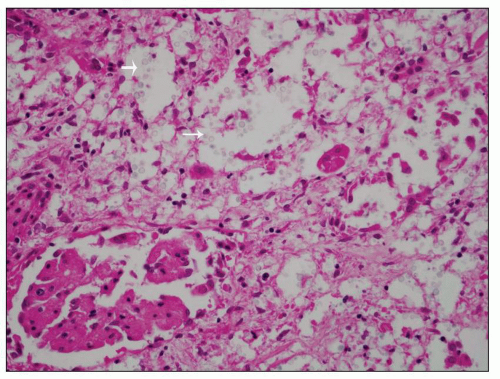

FIGURE 24.7 In acute pyelonephritis, neutrophils appear first in peritubular capillaries (arrow). (H&E; ×400.) |

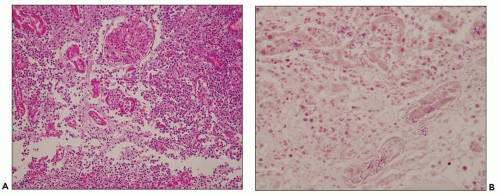

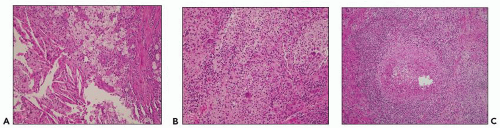

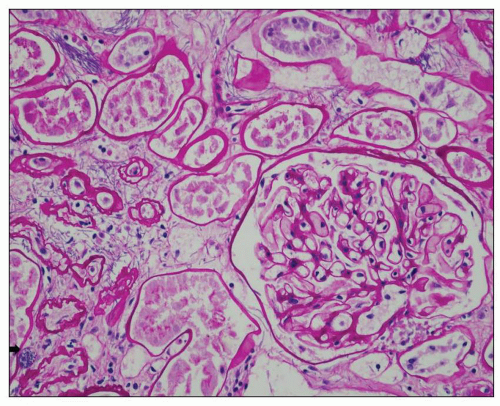

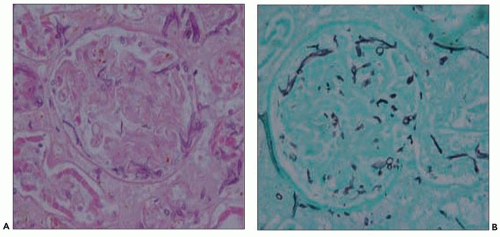

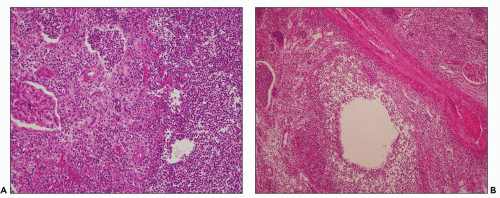

FIGURE 24.8 Acute pyelonephritis. A: Pools of neutrophils destroy tubules; glomeruli are remarkably unaffected. B: Abscess formation. (H&E; ×200.) |

and neutrophil recruitment to the kidney, which may worsen renal injury, but there is considerable controversy on the pathology of ATN in humans compared to animal models (38). Recent studies suggest that interstitial injury activates innate immunity and the inflammasome, a new concept to explain inflammatory responses in kidney disease in various conditions including ATN and obstruction (39,40). Innate immune response in the context of kidney infection is discussed further under pathogenesis of pyelonephritis.

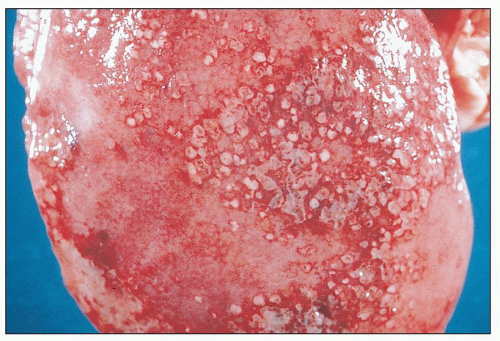

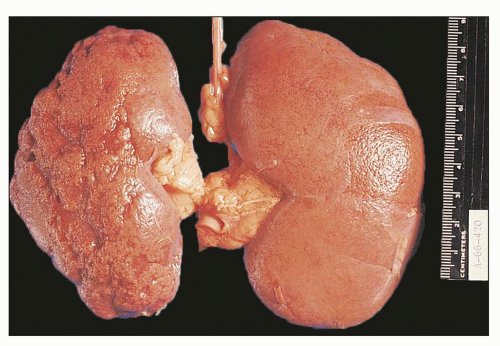

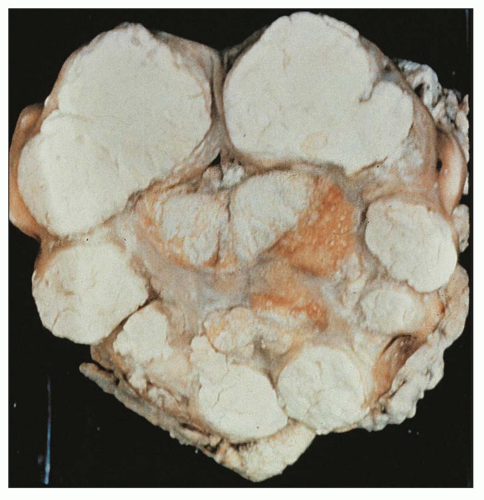

FIGURE 24.9 Diffuse suppurative nephritis. The subcapsular surface shows numerous discrete and focally confluent, whitish-yellow abscesses of variable size. |

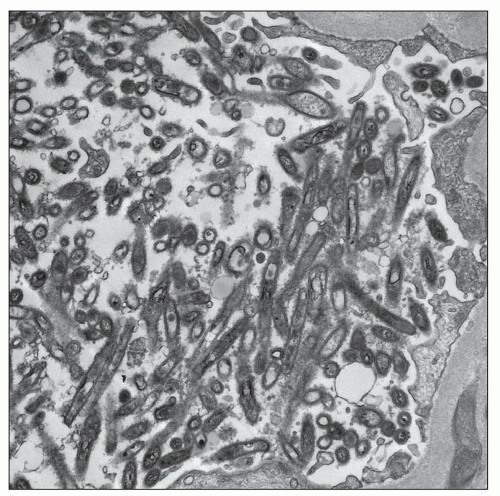

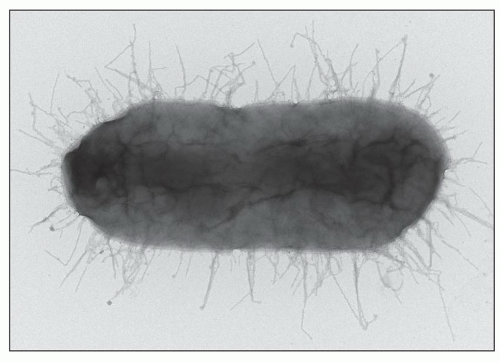

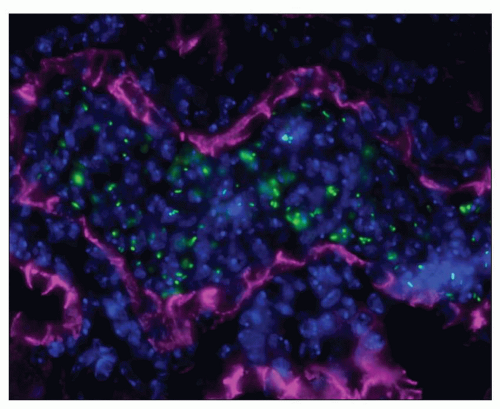

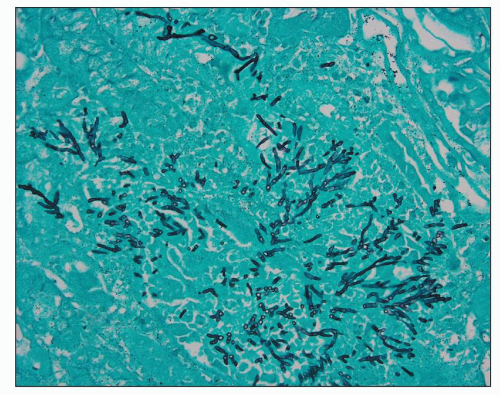

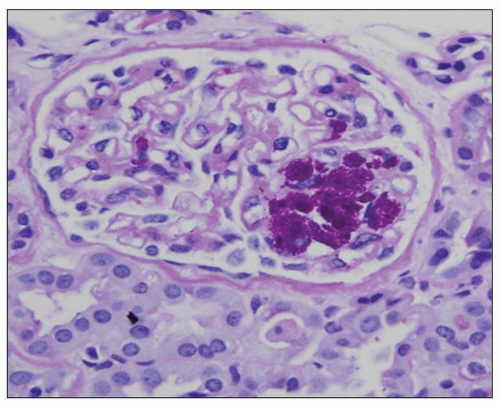

to hematogenously spread infection to the kidney. For example, the case shown in Figure 24.11 is from a 68-year-old man with history of weight loss, fatigue, weakness for 2 years, history of colon cancer, and documented blood infection. The glomeruli are filled with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive rod-shaped Tropheryma whippeli bacteria, better seen by electron microscopy (Fig. 24.12). Acute pyelonephritis was evident in the surrounding renal parenchyma, but the glomeruli are devoid of inflammation in spite of the presence of bacteria.

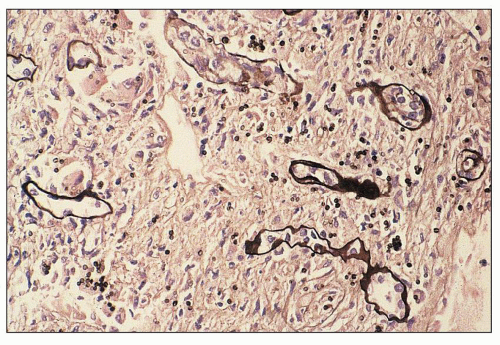

FIGURE 24.11 Acute pyelonephritis from an immunocompromised patient with Tropheryma whippeli infection. PAS-positive organisms are found within the glomerular tuft. (PAS; ×400.) |

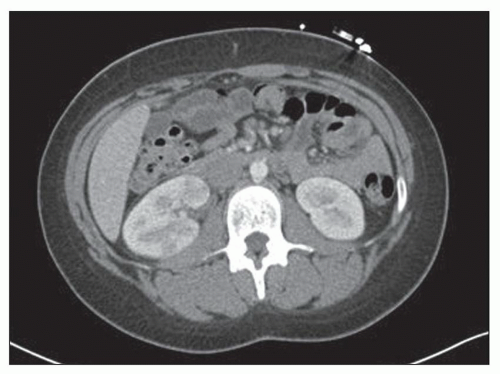

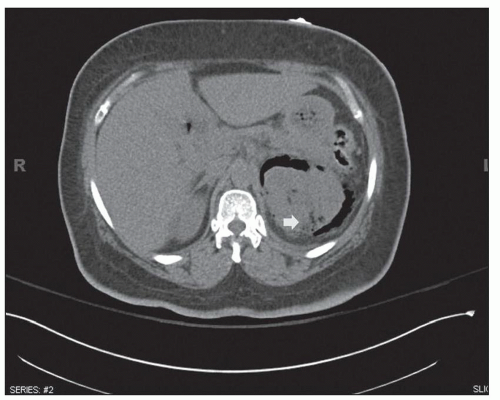

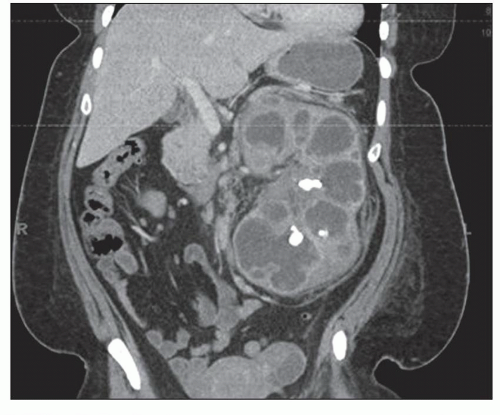

neurogenic bladder, alcoholism, and anatomic anomalies have also been found in association with this disease (43). Women are affected more often than are men, with a mean age in the sixth decade. Typically, only one kidney is involved, usually the left (3). Rarely, both kidneys are affected (3). Emphysematous pyelonephritis is associated with a 21% mortality rate (44). Patients may have nonspecific clinical symptoms including chills, fever, flank pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and pyuria. Patients may initially present with thrombocytopenia, acute renal failure, disturbance of consciousness, and shock, which are risk factors for poor outcome and mortality (44). Escherichia coli is the most common organism encountered, but others, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Proteus mirabilis, Candida spp., and Cryptococcus neoformans, have been described. Diagnosis can be made by CT, which also provides information for classifying the extent of the intrarenal and extrarenal disease, which has prognostic and therapeutic importance (2,3,26,27,44). Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a very serious condition that requires prompt and energetic treatment. Operative and nonoperative treatment with antibiotics is currently employed avoiding nephrectomy. The allograft kidney is rarely affected with only about 20 cases of emphysematous pyelonephritis reported in the literature (43). A new radiologic classification is proposed taking into account the extent of gas accumulation in the kidney (class 1 to 4) to help guide appropriate and timely management of patients (44). The pathogenesis of the condition is not clear, but many features are similar to those described in S. aureus infection, suggesting a blood-borne infectious etiology. Four factors involved in pathogenesis include gas-forming bacteria, high tissue glucose, impaired tissue perfusion, and a defective immune response (44,45,62). Successful medical therapy is possible in some cases (45).

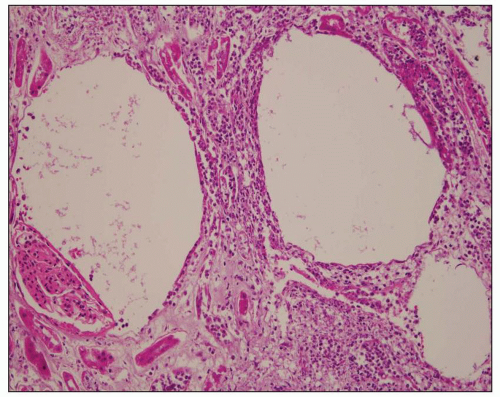

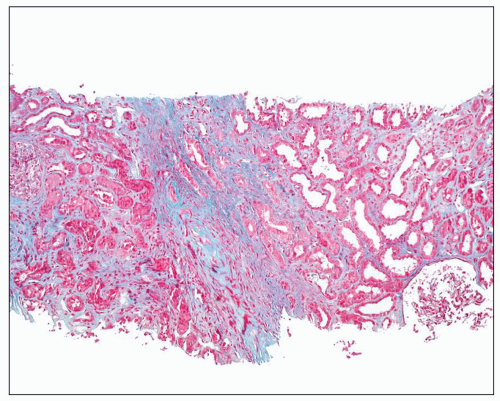

dilated as are all the calyceal systems. The pelvic wall is thickened and granular and often shows signs of congestion owing to active infection. Some cases are associated with stones, typically found in the pelvis and calyces. As a consequence of generalized dilatation of the collecting system, it is common to find a thinned parenchyma, particularly in areas aligned with dilated calyces (Fig. 24.17B). Blunting of the papillae is almost invariably a feature. In some cases, large, discrete scars are seen, as in kidneys with the back-pressure type of reflux nephropathy. Often, however, scars are not apparent, and parenchymal thinning is uniform.

calyces, the parenchyma also contains foci of yellowish material. In cases with significant pelvicalyceal dilatation, there may be considerable cortical thinning.

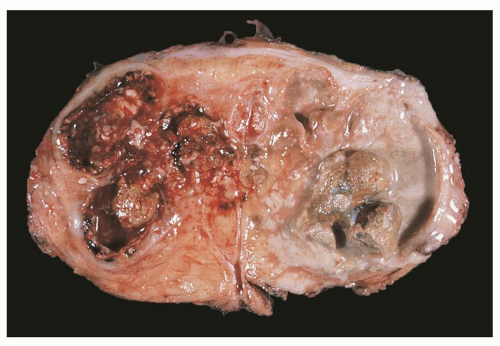

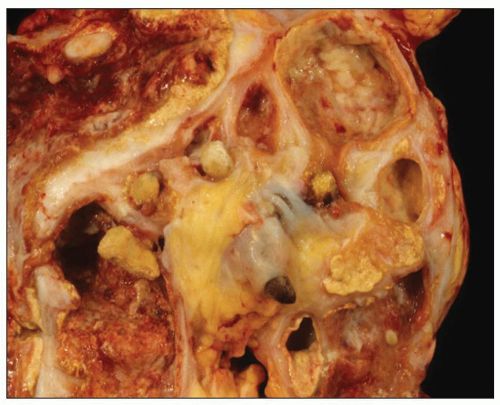

FIGURE 24.20 Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Friable, yellow tissue surrounds the dilated calyces. Numerous calculi are evident. |

follow-up analyzed in the review by Tam et al., six developed significant renal impairment with three requiring renal replacement therapy.

PAS. In contrast to malakoplakia, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies are conspicuously absent (63). Given the striking similarities to malakoplakia, it has been proposed that megalocytic interstitial nephritis is a prediagnostic phase of malakoplakia. The differential diagnosis of all entities above includes malignancy, particularly if the lesion is solitary.

TABLE 24.2 UTI pathogenesis: key facts | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UTIs, especially with regard to renal involvement. The receptorbinding adhesin at the tip of P fimbriae is pap G. There are three classes of G-tip proteins (87). Class II-tip adhesin is associated with pyelonephritis and class III-tip adhesin with cystitis.

caseous necrosis (Fig. 24.28). Organisms are usually found in such lesions. Often, a mononuclear infiltrate of lymphocytes, monocytes, and plasma cells is also present. The tubercle may be contained and heal, or the infection may expand. If the medulla is involved, the infection may reach the renal pelvis, allowing release of microorganisms into the urinary tract.

variable interstitial inflammation with lymphocytes and plasma cells amidst calcific foci, probably representing calcified tubercles.

is rare (136). In tissue sections, pseudohyphae and rounded yeast forms, 2 to 4 µm in diameter, predominate (Fig. 24.30). Although Candida can be seen in sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, they are more readily identified with PAS or Grocott methenamine silver stains.

tract and mucosal surfaces, cutaneous wounds, or intravenous access lines. Renal aspergillosis is frequently the result of hematogenous dissemination, usually from invasive bronchial infection, necrotizing pneumonitis, or infarct by aspergilli. Patients receiving corticosteroids, neutropenic patients, diabetics, and immunocompromised patients (26) are particularly at risk. Less frequently, the kidneys may be involved through the ascending route (141). Renal parenchymal infections may produce symptoms comparable to those of acute pyelonephritis. The urinary tract may be obstructed by growth of mycelium, and fungus balls may be passed into the urine.

immunosuppression. The disease is not contagious. Renal involvement is usually clinically silent, and compromise of renal function is uncommon.

FIGURE 24.33 Renal involvement in systemic cryptococcosis. Yeast within glomeruli and tubules are separated by clear halos corresponding to their thick capsule. (H&E; ×200.) |

encoded molecules and facilitate a TH1 response at the locale of the renal parenchyma. The subsequent inflammatory response may injure the kidney. As a phenotypic disease example of virally induced innocent bystander damage, the hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS), in which nonmalignant proliferations of activated macrophages infiltrate many organs, can cause acute renal failure. Viral triggers such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), parvovirus, and CMV have been described in HPS. Heterologous immunity, in which established memory T-cell responses to a previously encountered pathogen, can have a major impact on the course and outcome of a subsequent infection with an unrelated pathogen. Heterologous immunity is dependent on the sequence of infections, the prior T memory network at the time of the infection, and can be either beneficial or detrimental to the host in transplantation settings (149).

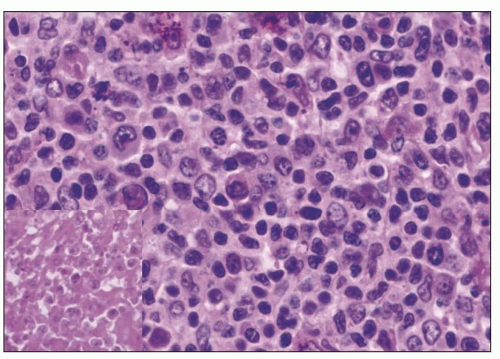

of small lymphoid cells, plasma cells, and rare immunoblasts (Fig. 24.36). In “polymorphous PTLD,” the mixed morphotype of the infectious mononucleosis-type reaction is repeated but with a greater number of immunoblasts, occasional atypical immunoblasts, cells with irregular nuclei resembling centrocytes, increased mitoses, and frequently, necrosis (Fig. 24.37). PTLD involving renal allografts does not show the lymphocytic tubulitis or vasculitis of cellular rejection.

TABLE 24.3 World Health Organization categories of PTLD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 24.36 Early mononucleosis-like infiltrate of PTLD. The interstitial infiltrate is mostly mature lymphocytes. Only rare immunoblasts are seen. (H&E; ×27.) |

FIGURE 24.37 Polymorphous PTLD. The number of transformed cells is increased, with many immunoblasts. Focal necrosis is seen (inset). (H&E; ×27.) |

for PTLD, including studies for EBV and C4d, should be undertaken in renal allograft recipients with dense lymphoid infiltrates showing atypia and/or interstitial hemorrhage.

adenovirus are well described in immunosuppressed patients including solid organ and bone marrow transplant patients and may present as disseminated infection (180). Adenovirus infection may also present as acute hemorrhagic cystitis in renal transplant patients (181). Adenovirus viremia is cited in approximately 7% of renal transplant patients (182), and the virus is excreted in approximately 11% (183). Serotypes 7, 11, 34, and 35 constitute most of the cases (184). Adenovirus has tropism for epithelial cells via coxsackievirus and AdV receptors, class I human leukocyte antigen molecules, and sialoglycoprotein receptors (185); CD46; and fiber knob gene protein (186). Secondary interactions with integrins may be needed for virus internalization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree