ANCA positive compared with those who are ANCA negative (23). ANCA-associated pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis is the most common cause for the renal component of pulmonary-renal vasculitic syndrome (24,25). For example, in a study of 88 patients with pulmonary-renal syndrome by Niles et al. (24), 48 (55%) had ANCA, 6 (7%) had anti-GBM antibodies, and 7 (8%) had both. Thus, 63% of patients with pulmonary-renal syndrome had ANCA.

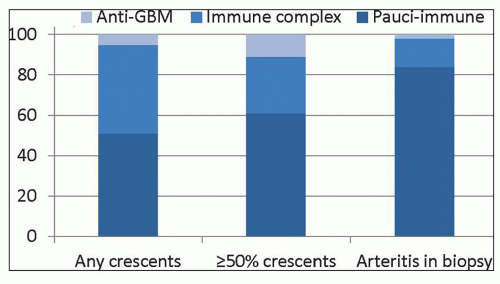

FIGURE 16.1 Frequency of immunopathologic categories of glomerulonephritis in native kidney biopsies evaluated by immunofluorescence microscopy in the University of North Carolina Nephropathology Laboratory. Data are derived from 540 patients with any crescents, 195 patients with ≥50% crescents, and 37 patients with arteritis in the biopsy (137). The anti-GBM patient with arteritis was ANCA positive. |

TABLE 16.1 Definitions of ANCA-associated vasculitis, microscopic polyangiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis based on the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitis | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

TABLE 16.2 Comparison of approximate frequency of manifestations of microscopic polyangiitis to several other forms of small-vessel vasculitis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

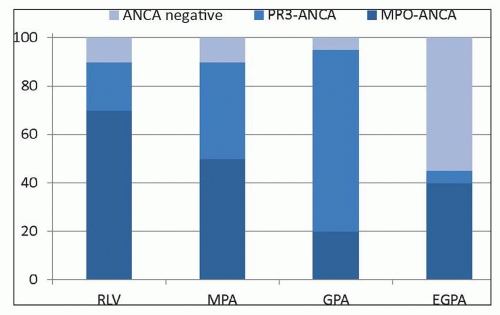

one third of patients with MPA, and pulmonary involvement occurs in about one half, although, by definition, it is caused by vasculitis alone (usually alveolar capillaritis) rather than by granulomatous inflammation. Thus, clinical signs and symptoms of respiratory tract disease alone are not adequate for distinguishing between MPA and GPA. In a given patient, it may be difficult or impossible to confirm or rule out granulomatous inflammation; thus, it is not always possible to distinguish confidently between MPA and GPA. This problem is offset by the knowledge that the treatment of both expressions of small-vessel vasculitis is similar in the presence of active major organ damage, such as crescentic glomerulonephritis or pulmonary capillaritis; therefore, if a diagnosis of ANCA-associated pauci-immune small-vessel vasculitis can be made, treatment can proceed even if it is not clear whether the patient has MPA or GPA. For clinical management, including selection of treatment regimen and prognostication, in addition to diagnostic classification of patients with ANCA disease based on clinicopathologic features into MPA, GPA, EGPA, and renal-limited disease, the ANCA antigen specificity should be included in the diagnosis (e.g., MPO-ANCA MPA, PR3-ANCA MPA, or ANCA-negative MPA) because the ANCA specificity correlates as well or better than the clinicopathologic category with clinical outcomes, such as response to treatment, likelihood of relapse, renal survival, and patient survival (27,50,57). In addition, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) revealed the strongest genetic associations with antigenic specificity of ANCA, not with the clinicopathologic syndrome (57). PR3-ANCA was associated with HLA-DP and the genes encoding α(1)-antitrypsin (SERPINA1) and proteinase 3 (PRTN3); and MPO-ANCA was associated with HLA-DQ (57).

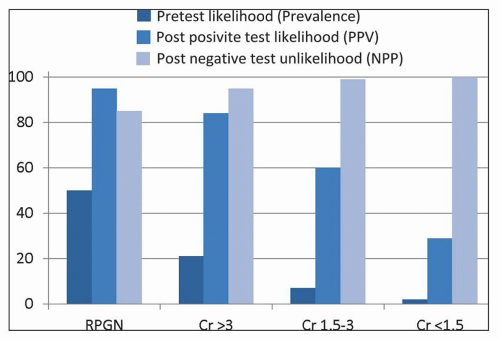

More precise determination of antigen specificity is accomplished by enzyme immunoassay. The most common cANCA specificity is for proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA) (93,94,95), and the most common p-ANCA specificity is for myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA) (6). p-ANCA that do not have specificity for MPO are associated with various inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Felty syndrome (18). Thus, a positive p-ANCA result in this context is a “false-positive” result with respect to pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis even though it is an analytically true positive result and is a true positive result for inflammatory bowel disease. Because of this and other instances in which a positive indirect immunofluorescence microscopy assay (IFA) result does not correspond to a positive MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA, an international consensus conference recommendation is to perform both IFA for p-ANCA and c-ANCA and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA when testing for the presence of pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis or small-vessel vasculitis (96). When both a positive IFA and positive ELISA are required to conclude that the ANCA serology is positive, this positive result has a sensitivity of approximately 81% and a specificity of approximately 96% for pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis (with or without systemic vasculitis) (16). Figure 16.2 shows the calculated predictive value of an ANCA serology result with this sensitivity and specificity. As with all diagnostic testing, the positive and negative predictive values of the test are dependent on the pretest likelihood of the disease, which in turn is determined by the prevalence of the disease in patients with the signs and symptoms of the patient being tested. As noted in Figure 16.1, pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis has a prevalence of approximately 50% in all patients with crescents and an even higher prevalence when there are more than 50% of glomeruli with crescents. Assuming a prevalence (pretest likelihood) of 50%, a positive ANCA result in a patient with signs and symptoms of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis would yield a posttest likelihood of the disease (positive predictive value) of 95%, and a negative result would yield a posttest likelihood of no disease (negative predictive value) of 85%. The negative predictive value in this instance is very close to the percentage of all patients with pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis who in fact are ANCA negative using first-generation ANCA immunoassays. When there is low pretest likelihood of pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis, for example, in patients with hematuria and proteinuria but no renal insufficiency, the major value of ANCA testing is to rule out ANCA disease or to increase the suspicion for ANCA disease to a level that will prompt more extensive and rapid diagnostic evaluation (e.g., renal biopsy). In this setting, a negative result provides a negative predictive value mathematically at essentially 100%. Although a positive result in this setting has a very low positive predictive value that certainly would not warrant immediate institution of immunosuppressive therapy, it does increase the likelihood of this life-threatening disease to a level that would warrant more careful and timely diagnostic evaluation.

with active disease reacted with a restricted set of epitopes that were not recognized by IgG from patients in remission. Interestingly, this assay method detected MPO-ANCA in ANCA-negative disease that reacted against a sole linear MPO epitope. This reactivity could only be detected using IgG rather than serum because serum contains a ceruloplasmin fragment that binds to MPO and blocks detection of these autoantibodies by routine serologic methods (97). Thus, some ANCA-negative patients appear to in fact have MPO-ANCA that is not detected by first-generation clinical ANCA assays; however, this experimental observation has not been confirmed, and an assay to detect these masked ANCA is not commercially available at this time.

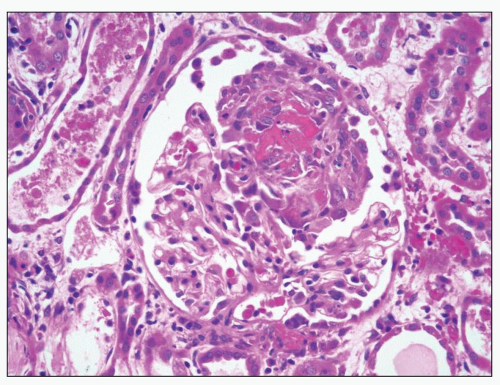

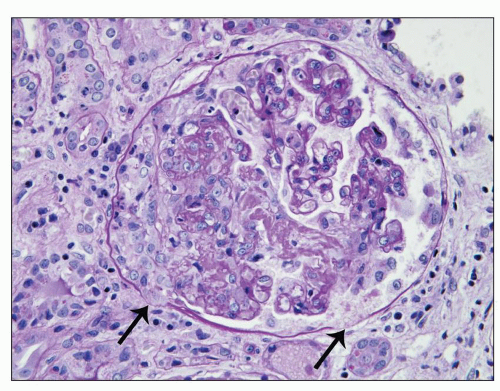

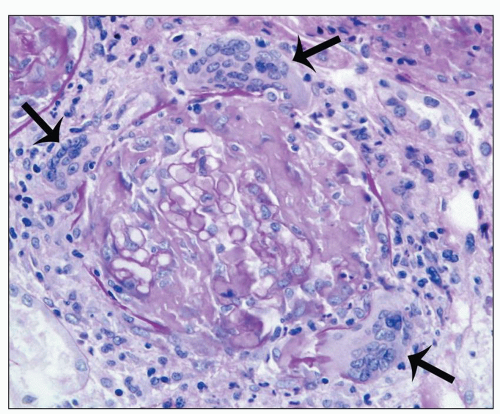

of the presence or absence of associated systemic vasculitis (2,3,11,12,21,22,36,70,71,107). The glomerular inflammation is accompanied by proportional nonspecific tubulointerstitial inflammatory lesions (107). In an analysis of 45 ANCA-positive patients with glomerulonephritis and systemic small-vessel vasculitis, renal biopsies demonstrated crescents in 93% of patients and glomerular necrosis in 98% (2). In a study of 32 renal biopsies from patients with MPA, Savage et al. (36) identified glomerular segmental necrosis in 100% and crescent formation in 88%. Likewise, in a study of 20 renal biopsies in MPA by D’Agati et al. (108), 80% of 20 specimens had segmental glomerular necrosis, and 85% had crescents. The severity of acute lesions ranges from focal segmental fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation affecting less than 10% of glomeruli to severe diffuse necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis with global necrosis of virtually all glomeruli. On average in a given renal biopsy specimen, 45% to 55% of glomeruli have crescents, and 20% to 25% of glomeruli have fibrinoid necrosis (12). The fibrinoid necrosis usually is accompanied by crescent formation. For example, Hauer et al. (109) identified fibrinoid necrosis in the absence of extracapillary hypercellularity in only 1 of 87 glomeruli from renal biopsy specimens of pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis that were examined by serial section. Eisenberger et al. (23) compared glomerular crescents, necrosis, and sclerosis in patients with ANCA-negative pauci-immune glomerulonephritis and patients with ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis and found no significant difference, which corresponds to our experience.

of fibrinoid necrosis in pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis often contain neutrophil granule constituents indicating that there has been extensive neutrophil activation and degranulation at these sites. For example, using double immunohistochemical staining procedures, Bajema et al. (111) identified PR3, MPO, elastase, and lactoferrin at sites of glomerular fibrinoid necrosis.

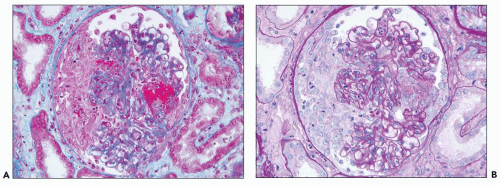

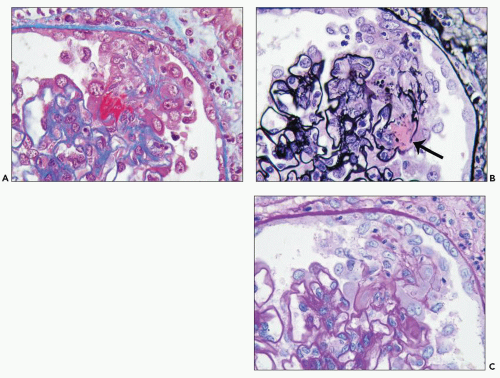

FIGURE 16.6 Glomerulus from the same patient as in Figure 16.5 stained with Masson trichrome (A), Jones silver methenamine (B), and PAS (C) showing a small focus of fibrinoid necrosis with adjacent early crescent formation. The fibrinoid material is bright red (fuchsinophilic) with the trichrome stain (A) and is associated with breaks in the glomerular basement membrane that can be seen best with the Jones stain (arrow in B). |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree