heavy proteinuria and frequent progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (1). Secondary causes of FSGS include genetic defects, viral infections, drugs, toxins, and adaptive responses mediated by altered glomerular hemodynamics (referred to as glomerular hypertension) (Table 6.1). Focal and segmental glomerular scarring also occurs as a nonspecific pattern of injury in the course of progression of diverse inflammatory, proliferative, and thrombotic glomerular diseases.

of primary FSGS has grown, and it is now the leading cause of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) in both children and adults (10) and the most common primary glomerular disease causing ESRD in the United States (11,12).

TABLE 6.1 Etiologic classification of FSGS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

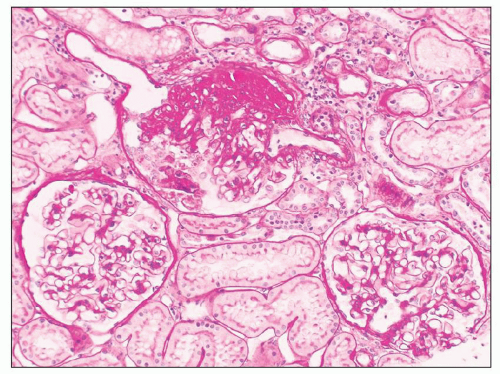

multiple individual lesions (Fig. 6.8) may exist in a given glomerulus, as revealed by serial sectioning and three-dimensional reconstructions (40). Juxtamedullary glomeruli appear to be more vulnerable to developing FSGS than superficial glomeruli, likely because of their greater single-nephron glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and higher glomerular capillary pressures and flow rates (41,42).

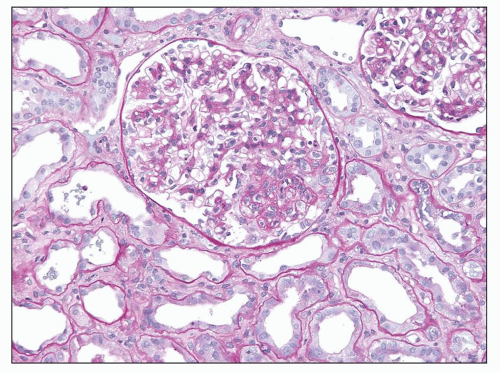

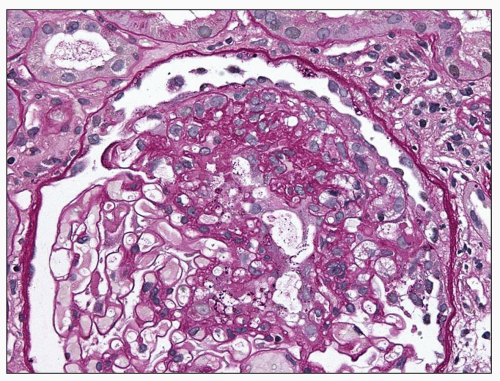

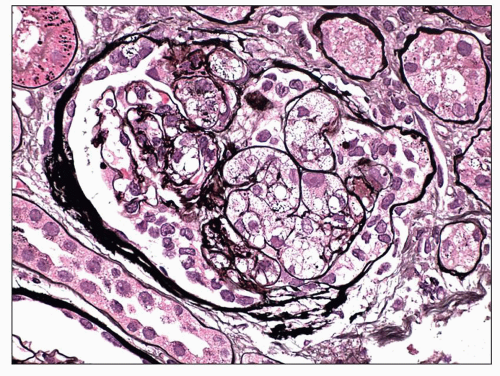

FIGURE 6.3 Primary FSGS, NOS. With a silver stain, the extracellular matrix is argyrophilic (black), whereas hyaline is pink. (Jones methenamine silver [JMS] stain, ×600.) |

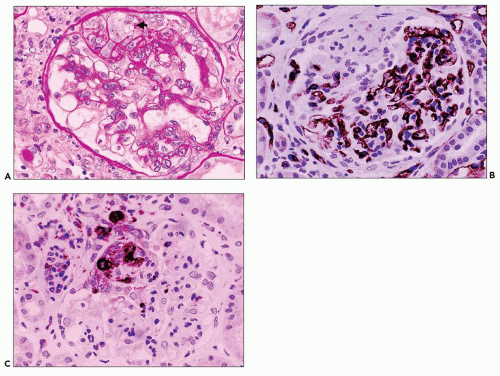

cells may be seen in areas of segmental sclerosis (Figs. 6.11 and 6.12) and are sometimes numerous, leading to expansion of the glomerular tuft (Fig. 6.13). These cells express monocyte markers, such as CD68, but it is unclear if they derive from circulating macrophages or from transdifferentiation of resident glomerular endothelial or mesangial cells.

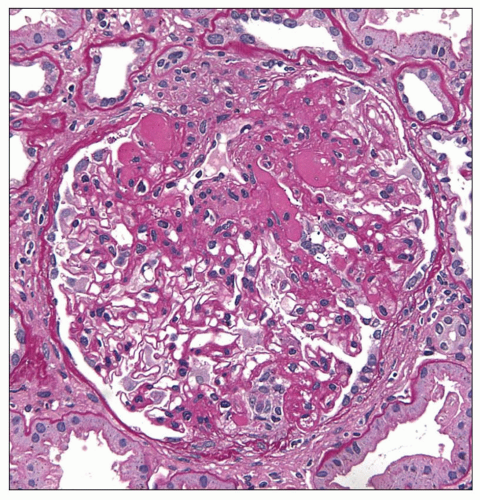

FIGURE 6.5 Primary FSGS. Hyalinosis and matrix both stain pink with PAS, but hyaline has a glassy appearance. (PAS, ×400.) |

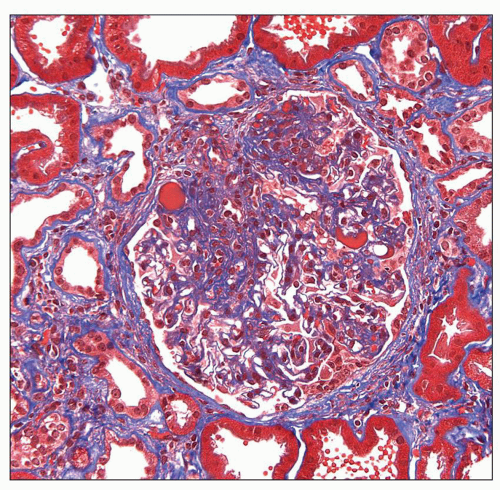

FIGURE 6.6 Primary FSGS. Hyalinosis stains bright red and extracellular matrix stains blue with trichrome stain. (Trichrome stain, ×400.) |

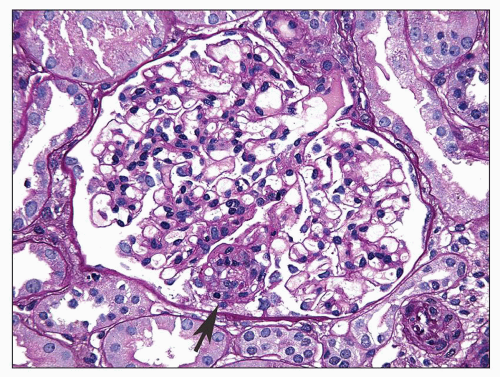

FIGURE 6.7 Primary FSGS. A single segmental lesion (arrow) with endocapillary hypercellularity and mild hyalinosis involves the periphery of the glomerular tuft. (PAS, ×400.) |

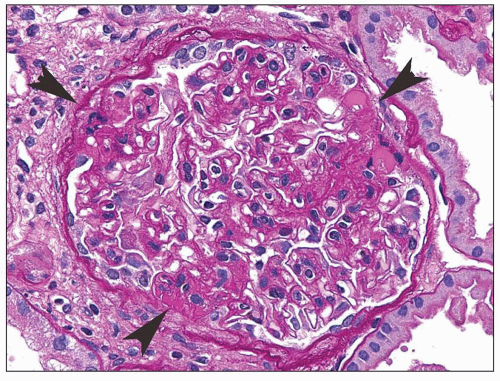

FIGURE 6.8 Primary FSGS. Three discrete lesions (arrowheads) of the matrix and/or hyaline are present in the same glomerulus. (PAS, ×400.) |

FIGURE 6.10 Primary FSGS. A segmental sclerosis lesion with “capping” of overlying visceral epithelial cells. (PAS, ×400.) |

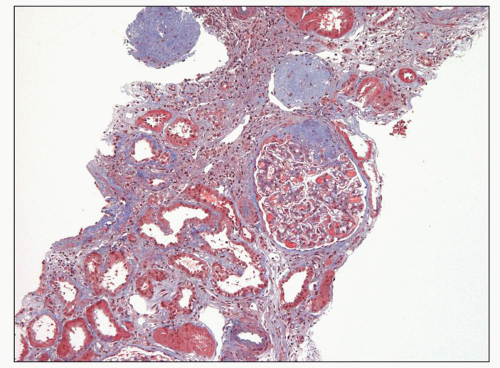

mild to severe, but are generally commensurate with the degree of glomerulosclerosis (Fig. 6.18). Interstitial foam cells may be seen, either singly or in aggregates, in cases with long-standing proteinuria. In the setting of severe unremitting nephrotic syndrome and marked hypoalbuminemia, proximal tubules may exhibit degenerative and regenerative changes resembling acute tubular necrosis (Fig. 6.19). Arterial vessels show changes related to hypertension and/or aging.

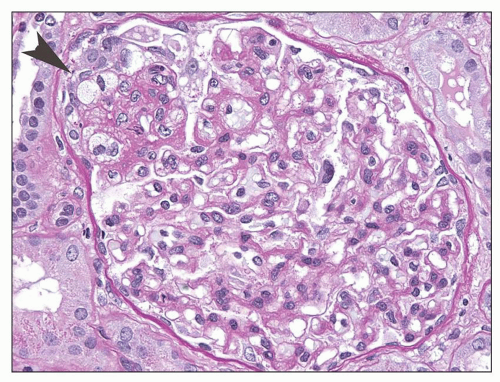

FIGURE 6.11 Primary FSGS. A segmental lesion contains endocapillary foam cells (arrowhead). (PAS, ×400.) |

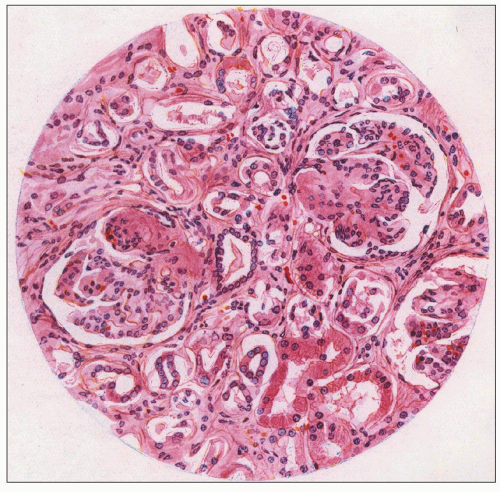

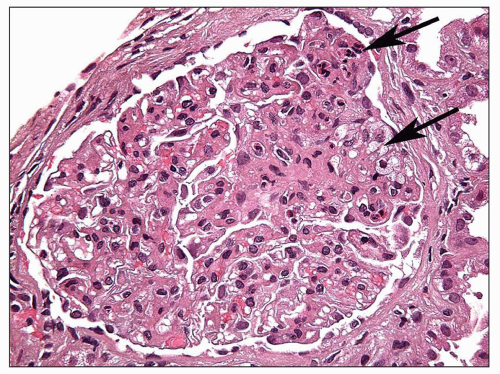

FIGURE 6.12 Primary FSGS. A segmental sclerosis lesion contains endocapillary foam cells, as well as some infiltrating leukocytes (arrows) (H&E, ×400) |

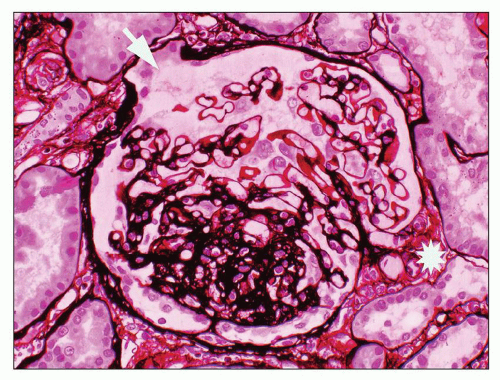

FIGURE 6.15 Primary FSGS, NOS. A segmental sclerosis lesion with a small adhesion involves neither the hilum (asterisk) nor the tubular pole of the glomerulus (arrow). (JMS stain, ×330.) |

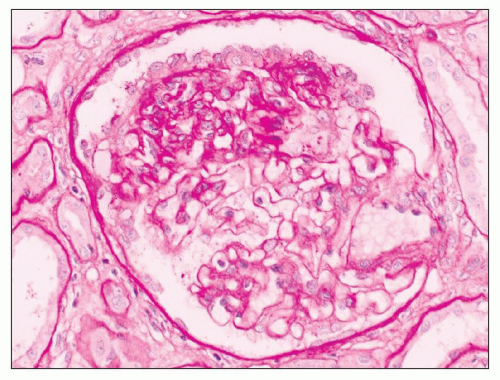

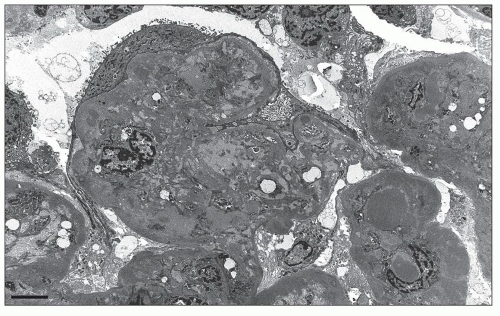

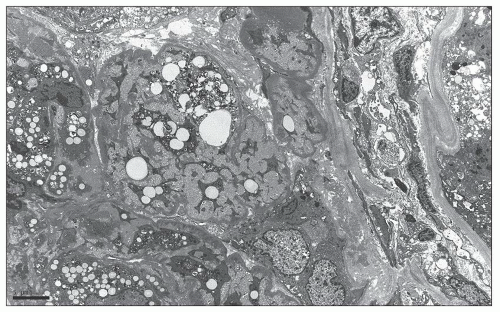

FIGURE 6.16 Primary FSGS, perihilar variant. Segmental sclerosis and hyalinosis located in the perihilar region (vascular pole). (PAS, ×600.) |

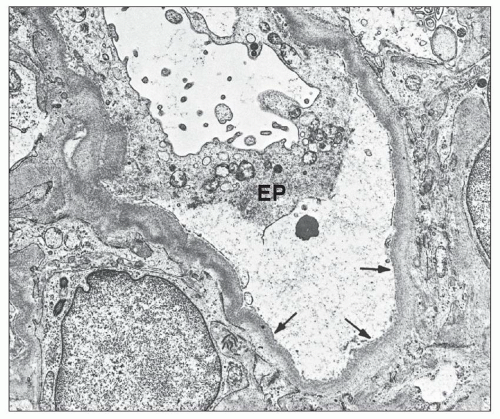

Many filtration slit diaphragms become displaced or lost. Podocyte actin filaments typically undergo rearrangement to form a dense cytoskeletal “mat” parallel to the direction of the GBM, in the basal cytoplasm above the effaced foot processes. Detachment and lifting of injured podocytes from the GBM may be seen (Fig. 6.23). These changes are often followed by the laying down of a lamellated neomembrane between detached visceral epithelial cells and the underlying GBM. Recent studies suggest that this looser matrix, which is less electron dense than the normal GBM, is derived from parietal cells that have replaced lost podocytes (43). Cytoplasmic electron dense protein droplets are common in cases with severe proteinuria. Hyalinosis lesions are characterized by accumulation of amorphous electron dense material, sometimes containing clear, rounded inclusions representing entrapped lipid and typically localize to the infra-membranous region (i.e., between the endothelial cell and the GBM). Endocapillary foam cells are rounded cells with electron-lucent lipid-rich cytoplasmic vacuolization (Fig. 6.24).

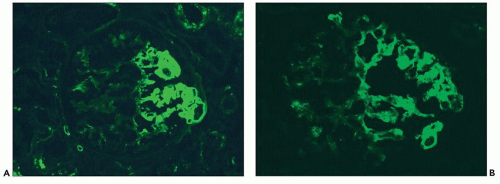

FIGURE 6.20 Immunofluorescence microscopy shows segmental glomerular tuft staining for IgM (A) and C3 (B). (FITC anti-human IgM [A] and FITC anti-human C3 [B], ×330.) |

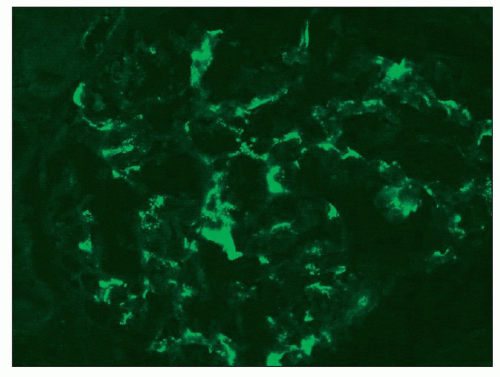

FIGURE 6.21 Immunofluorescence microscopy shows finely granular mesangial staining for IgM. (FITC anti-human IgM, ×330.) |

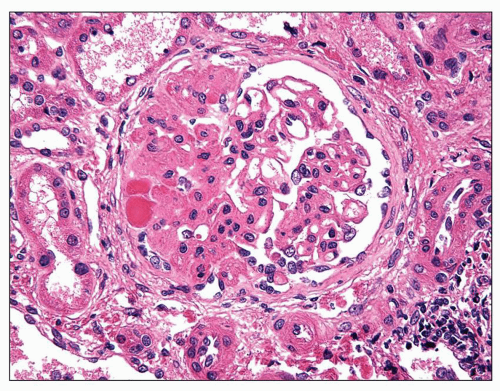

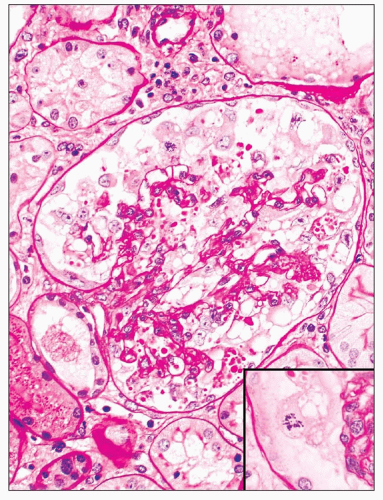

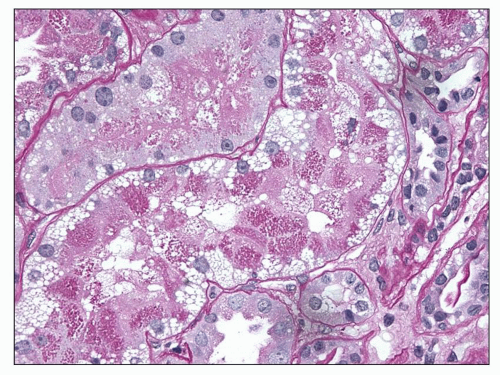

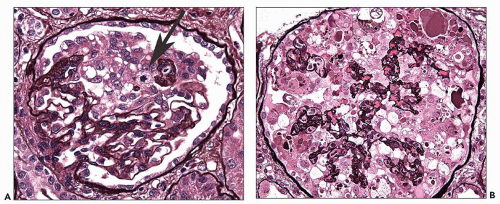

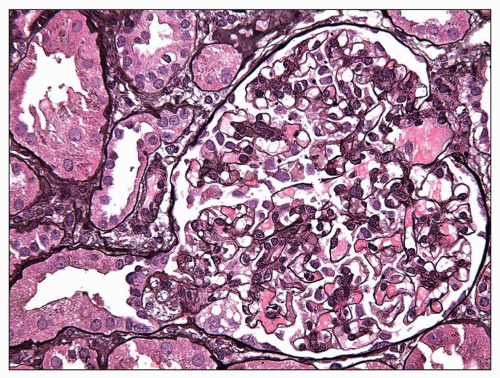

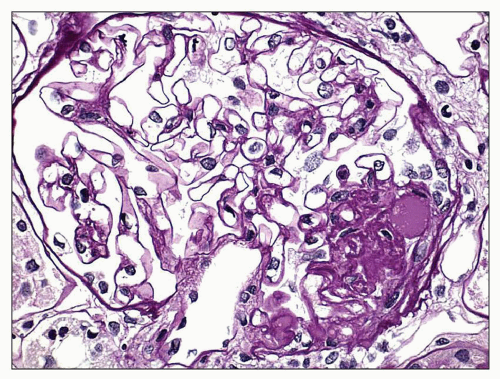

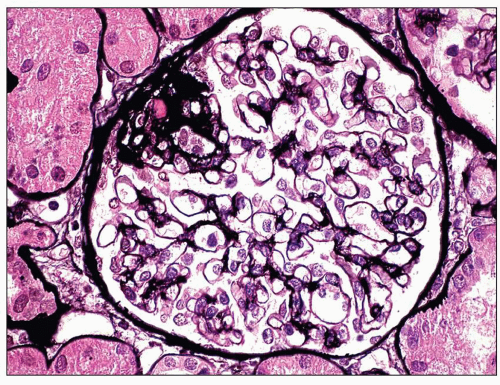

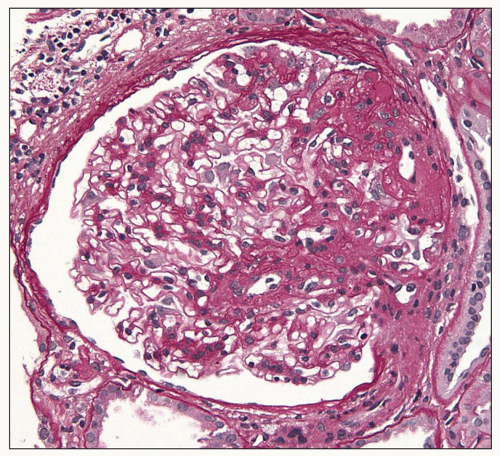

some residual patent capillaries,” whereas a global lesion affects the entire glomerular tuft (62). The finding of segmental (Fig. 6.26A) or global (Fig. 6.26B) glomerular capillary collapse with overlying visceral epithelial cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia in at least one glomerulus warrants a diagnosis of the collapsing variant of FSGS, irrespective of the findings in other glomeruli. Excluding collapsing lesions, the finding of a single segmental lesion involving the tip domain (outer 25% of the tuft next to the proximal tubule origin) where the tubular pole is identified is diagnostic of the tip variant (Fig. 6.27). After excluding collapsing and tip lesions, the finding of one glomerulus with segmental expansile endocapillary hypercellularity obliterating capillary lumina (with or without foam cells, hyalinosis, infiltrating leukocytes, karyorrhexis, and epithelial cell hyperplasia) is classified as cellular variant (Figs. 6.13 and 6.28). Perihilar variant is defined as segmental hyalinosis and sclerosis contiguous with the glomerular hilum affecting the majority (≥50%) of glomeruli with segmental lesions, excluding collapsing, cellular, and tip lesions (Fig. 6.29). All other cases are classified as FSGS NOS variant, which by default represents the common, “classic” or generic lesion of segmental sclerosis.

TABLE 6.2 Histologic variants of FSGS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

matrix accumulation in the acute collapsing lesions, but this may be present in other glomeruli. Hyalinosis lesions are rare in this variant. Capillary collapse is accompanied by prominent epithelial cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia within the Bowman space. The epithelial cells typically line the external surface of the glomerular tuft but may fill the Bowman space, forming a “pseudocrescent” (Fig. 6.31). Serial sections have shown that these lesions are often continuous with the parietal epithelial cell layer; however, these cells usually lack the spindled morphology, intercellular matrix, and pericellular

fibrin seen in true inflammatory crescents. Features of fibrinoid necrosis and ruptures of the GBM or Bowman capsule, which are often identified in crescentic glomerulonephritis, are absent. Visceral epithelial cell nuclei are typically enlarged and show vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli; rarely, mitotic figures or binucleated cells are evident (see Fig. 6.25) (56). The swollen epithelial cells often contain large cytoplasmic protein droplets, coarse cytoplasmic vacuoles, and lipid droplets; they may have prominent subpodocyte, tunnel-like spaces that raise the cell bodies off the underlying basement membrane (Fig. 6.32). Proximal tubules frequently show degenerative and regenerative changes (Fig. 6.33), and tubular microcysts (dilated tubules filled with proteinaceous casts) are commonly seen (Fig. 6.34). Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis are often severe and disproportionate to the degree of glomerulosclerosis. Foot process effacement is usually severe. Endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions (TRIs) are not a feature of primary collapsing FSGS but may be seen in secondary collapsing glomerulopathy associated with interferon therapy (71), HIV infection (60), or the podocytopathy of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (72).

FIGURE 6.28 Primary FSGS, cellular variant. There is segmental expansion of the glomerular tuft by endocapillary foam cells, occluding capillary lumina. (Jones stain, ×600.) |

tubulointerstitial scarring is not significantly worse in NOS compared to the other variants, implying that NOS is not just an advanced stage of the other variants (64). Thus, the NOS variant may occur ab initio or other variants may evolve into NOS over time.

TABLE 6.3 Frequency of Columbia Classification morphologic variants in primary FSGS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 6.4 Renal outcomes in primary FSGS by histologic variant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree