EPIDEMIOLOGY OF VASCULITIS

The incidence of vasculitis has been difficult to determine, largely because of an inconsistent classification strategy. The advent of the Chapel Hill Nomenclature System allowed for a more precise estimation of incidence and prevalence. The incidence of giant cell arteritis varies from 15 to 30 per million in individuals older than 50 years. There is an increased incidence with age and a female-to-male ratio of 2:1.

1 Giant cell arteritis is more common in Caucasians and is uncommon in African Americans. Takayasu arteritis has been described worldwide, but the disease is much more prevalent in Japan, where there are approximately 150 new cases per year. In Olmstead County, Minnesota, the incidence is 2.6 cases per mission per year.

The incidence of vasculitis associated with ANCA appears to be on the order of 10 to 20 cases per million.

1 In contrast, polyarteritis nodosa has become a rare disease. It is possible that the perceived increase in the incidence of microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) is a consequence of the development and widespread use of ANCA testing. Nonetheless, the incidence of MPA appears to have been more common in the 1990s than in the 1980s (19.8 versus 7 cases per million). Two interesting studies reported a much higher incidence of ANCA vasculitis. One study reported a much higher incidence in Alaskan Indians in which all cases were associated with hepatitis B.

2 The other report from Kuwait after the Gulf War found an increased incidence of 16 cases per million of polyarteritis nodosa and 24 cases per million of MPA.

3 The incidence of GPA was 0.7 per million per year from 1980 to 1986, increasing to 2.8 per million per year from 1987 to 1989. There was an increase in the annual prevalence from 28.8 per million in 1990 to 64.8 per million in 2005 in a primary care population.

4 In the 1990s the prevalence of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, was closer to 10.6 cases per million in the United Kingdom. The annual incidence of eosinophilic granulomatosis (EGPA) ranges between 0.5 and 6.8 cases per million.

5 The prevalence of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), MPA, GPA, and EGPA in a large multiethnic suburb of Paris based on a three-source capturerecapture method during the calendar year 2000 was estimated per 1,000,000 adults to be 30 for PAN, 25 for MPA, 24 for GPA, and 11 for EGPA. The overall prevalence was 2.0 times higher for subjects of European ancestry than for non-Europeans (

P = .01).

6

DIAGNOSTIC CLASSIFICATION AND PATHOLOGY OF VASCULITIDES

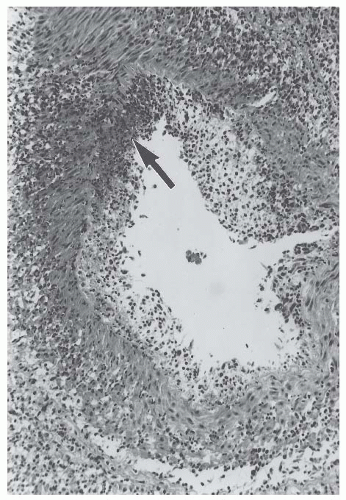

ANCA vasculitis can affect any vessel in the body and thus can cause various clinical signs and symptoms. Most of these manifestations are indicative of vessel involvement in a particular organ rather than a specific pathologic category of disease. Therefore, ANCA vasculitis cannot be accurately diagnosed on the basis of clinical features alone. Serologic and other laboratory data can be very helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis or providing additional support to a presumptive diagnosis, but data are rarely definitive. As with all tissues, vessels have a limited number of nonspecific patterns of response to injury. For example, many different inflammatory stimuli cause histologically indistinguishable acute and chronic inflammation with and without necrotizing or granulomatous features. To further complicate pathologic evaluation, vasculitic lesions evolve through various stages of active (

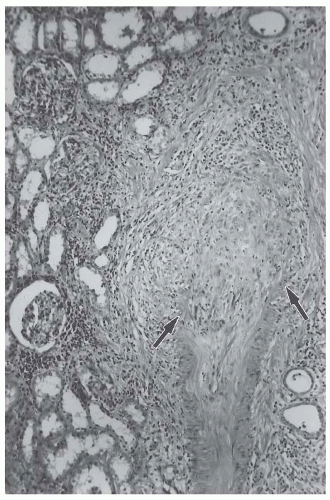

Fig. 48.1) and sclerosing injury (

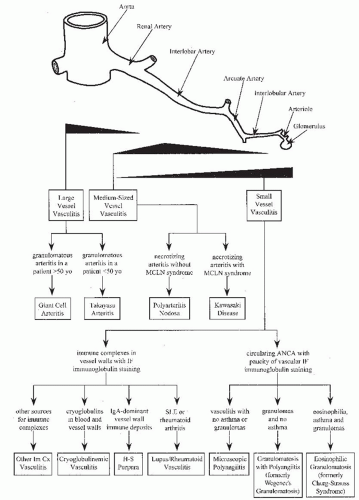

Fig. 48.2). Specific categories of vasculitis have a particular predilection for involvement of certain types of vessels, although there is so much overlap that type of vessel involvement alone does not provide adequate categorization (

Table 48.1,

Fig. 48.3). Therefore, vasculitis cannot be diagnosed accurately on

the basis of pathologic features alone, especially if these are evaluated only by routine light microscopy. Recently, a pathologic classification system for ANCA vasculitis has been validated for prognostication of renal outcomes based on renal biopsy,

7 but the best approach to a specific diagnosis continues to be a combination of clinical, laboratory, and histologic data to identify distinctive clinicopathologic categories of vasculitis. Vasculitis categorization schemes will continue to be improved in the future; however, current systems provide valuable guidance for prognostication and for determining the most effective management strategy.

There are a number of approaches to the categorization of vasculitis. The system used in this chapter is a proposed modification of the Chapel Hill Nomenclature System, a system agreed upon by an international group of clinicians and pathologists with a special interest in vasculitis (

Table 48.2).

8 There is a new nomenclature pending publication that recognizes a more specific categorization of vasculitides and abolishes eponyms.

Knowledge of the historical evolution of vasculitis categorization is helpful to understand the current diagnostic criteria for the classification of vasculitides. The following discussion of diagnostic classification includes a brief review of the historical events in the recognition of each category. The discussion is divided into sections discussing large-vessel vasculitis, medium-sized vessel vasculitis, and small-vessel vasculitis (

Tables 48.1,

Figs. 48.2 and

48.3). Large-vessel vasculitides were first recognized because of the reduced pulses and ischemic manifestations caused by chronic narrowing of major arteries. Medium-sized vessel vasculitides were first recognized because of the pseudoaneurysms caused by necrotizing lesions of medium-sized arteries, and small-vessel vasculitides were first recognized because of the glomerulonephritis and purpura caused by involvement of glomerular capillaries and dermal venules, respectively. Much of the discussion focuses on small-vessel vasculitides because these cause a higher frequency of renal disease.

TAKAYASU ARTERITIS AND GIANT CELL (TEMPORAL) ARTERITIS

Large-vessel vasculitis affects the aorta and its major branches, such as the arteries to the extremities and to the head and neck.

8 During the acute phase of disease, large-vessel vasculitis is characterized pathologically by inflammation that often

contains giant cells in the inflammatory infiltrates during the active phase of disease. The chronic phase is characterized by extensive vascular sclerosis with little or no active inflammation. Inflammatory and sclerotic thickening of the aorta and the arteries causes narrowing of lumina, which in turn causes ischemia and the resultant clinical manifestations. Involvement of the renal artery may cause renovascular hypertension. The two major categories of large-vessel vasculitis are Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis.

In 1856, William Savory described patients with diminished peripheral pulses who probably had Takayasu arteritis involving the major arteries to the extremities.

9 However, this category of vasculitis is named for Mikito Takayasu, a Japanese ophthalmologist who reported the ocular ischemic effects of this chronic granulomatous arteritis in 1908.

10 Takayasu arteritis, which also includes “aortic arch syndrome” and “pulseless disease,” most often involves the aorta and its major branches, although the pulmonary arteries may be affected.

11 Takayasu arteritis is most common in Asia, although it occurs worldwide. It rarely occurs in patients older than 40 years and is usually diagnosed during the second decade of life. Clinically, it often presents with reduced pulses, vascular bruits, claudication, and renovascular hypertension.

Giant cell arteritis rarely occurs in patients younger than 50 years and is most common in patients of northern European ethnicity.

12 Like Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis affects the aorta and its major branches; however, it has a much greater predilection for the extracranial branches of the carotid artery. Frequent clinical manifestations include headache, jaw claudication, blindness, deafness, tongue dysfunction, extremity claudication, and reduced peripheral pulses. Pathologic involvement of the renal artery is common in giant cell arteritis, but symptomatic renovascular hypertension is rare. This is in contradistinction to Takayasu arteritis, which often causes renovascular hypertension.

Giant cell arteritis has also been called “temporal arteritis,” partly because one of the earliest descriptions of this type of vasculitis in 1890 by Hutchinson emphasized temporal artery involvement.

13 However, the term “giant cell arteritis” is more appropriate than “temporal arteritis” because (1) not all patients with giant cell arteritis have temporal artery involvement and (2) vasculitides other than giant cell arteritis can cause temporal artery inflammation, such as polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

8 If a patient with clinical manifestations of temporal artery inflammation is found by temporal artery biopsy to have a necrotizing rather than a granulomatous arteritis, the differential diagnosis should include polyarteritis nodosa, MPA, GPA, and other forms of necrotizing vasculitis. The frequent association of polymyalgia rheumatica with giant cell arteritis is a useful diagnostic aid, although not all patients with giant cell arteritis have polymyalgia rheumatica and not all patients with polymyalgia rheumatica have giant cell arteritis.

Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis cannot be accurately distinguished on the basis of pathologic evaluation of involved arteries. Polymyalgia rheumatica and involvement of branches of the carotid artery are more in favor of giant cell arteritis, and preferential involvement of the aorta and arteries to the extremities is slightly in favor of Takayasu arteritis. However, the best diagnostic discriminator is age. If a patient with clinical or pathologic features of chronic granulomatous arteritis is older than 50 years, a diagnosis of giant cell arteritis is warranted, whereas a diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis is warranted if the patient is younger than 50 years.

8 The presence of renovascular hypertension in a child or a young adult is suggestive of Takayasu arteritis. In a patient older than 50 years, renal artery involvement by a chronic sclerosing process is more likely secondary to atherosclerosis than to giant cell arteritis, and Takayasu arteritis is essentially ruled out by the age of the patient.

Aortitis is a common feature of Takayasu and giant cell arteritis but is also associated with other vasculitides such as syphilis, tuberculosis, mycosis, Behçet disease, and Kawasaki disease. The most commonly involved vessels are the subclavian arteries in more than 90% of patients. Diagnostic differentiation between Takayasu and giant cell arteritis is largely based on age, with patients younger than 40 years having Takayasu arteritis and those older than 50 having giant cell arteritis. Aortic aneurysm rupture represents a morbid complication of giant cell arteritis. Aortitis may result in ischemic symptoms or infarction of the area supplied by the involved vessel. Asymptomatic aortitis may be a more common phenomenon than previously thought.

14

Clinical Presentation

According to the Giant Cell Arteritis Guideline Development Group

15 giant cell arteritis often presents with abrupt onset headache, which is classically temporal and unilateral but can be diffuse. Presenting complaints can also include scalp pain, jaw or tongue claudication, blurring of vision, diplopia or amaurosis fugax, fever, weight loss, fatigue, polymyalgic symptoms, or limb claudication. On physical exam, tender, thickened, or beaded temporal artery with diminished or absent pulse may be noted. Visual field defect, visual loss, or afferent papillary defect can be noted. Funduscopic exam classically reflects anterior ischemic optic neuritis with pale, swollen optic disc with hemorrhages. Central retinal artery occlusion, upper cranial nerve palsies, asymmetry of pulses and blood pressure, and bruits are also features of this disease.

Early presentation of Takayasu arteritis includes low-grade fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, arthralgia, and fatigue. Although clinical presentations vary significantly between patients, and Takayasu arteritis seems to be a relapsing and remitting syndrome, many patients have diminished or absent pulses, Reynaud phenomenon, vascular bruits, hypertension, mesenteric angina, retinopathy, aortic regurgitation, dizziness, seizures, or amaurosis fugax. Takayasu arteritis has been reported to accompany other autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus, Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and amyloidosis.

16,

17

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in large-vessel vasculitis include a mild anemia, elevated levels of C-reactive protein, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a generalized elevation in γ-globulin levels. Takayasu arteritis patients may be p- or c-ANCA positive. Other serologic results, including tests for lupus and infections, are typically negative. Patients typically present with only mild hematuria and proteinuria, except in patients with concomitant amyloidosis. The most common presentation is associated with hypertension and renal insufficiency, whereas renal failure is uncommon.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of giant cell and Takayasu arteritis is unknown. Current consensus is that large vessel vasculitis is likely autoimmune in origin. Chauhan et al. report that serum of patients with Takayasu arteritis contains antiaortic endothelial cell antibodies directed against 60 to 65 kDa heat-shock proteins.

18 Serum-containing antiaortic endothelial cell antibodies induced apoptosis of aortic endothelial cells. There is scant evidence for a direct link between antiaortic endothelial cell antibodies and the development of Takayasu arteritis, however.

There are several tantalizing clues that infectious agents may play a role in these diseases. In animals, there is evidence that gamma herpes virus 68 causes arteritis in mice lacking the interferon-

γ receptor. In humans, an association exists between giant cell arteritis and parvovirus B19 infection.

19 However, a study using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and immunohistochemistry techniques on 147 temporal artery biopsies found no evidence of parvovirus B19 DNA in the arteries of patients with giant cell arteritis.

20 A cyclic occurrence of disease, with a peak incidence occurring every 5 to 7 years, suggests an infectious cycle. Certain genetic factors are associated with the development of giant cell arteritis. This form of vasculitis is more common in individuals of Northern European descent living in Europe or the United States,

21 and there is clustering of cases among families.

22 The development of giant cell arteritis also correlates with the expression of HLA-DR4, which is also found in high frequency among patients with polymyalgia rheumatica.

23Giant cell arteritis may be a consequence of either or both the humeral and cellular immune responses. The clinical and experimental findings suggest that a cell-mediated process is most likely.

24 Most inflammatory cells that invade the vessel walls are CD4-positive T cells. Elevated levels of IL-6 correlate with the severity of the disease and decrease quite rapidly when glucocorticoids are administered.

25 Levels of several other cytokines and chemokines are similarly elevated. It is hypothesized that activated monocytes infiltrate the adventitia of large vessel walls via the vasa vasorum and become macrophages that then produce interferon-

γ and recruit additional leukocytes, including macrophages. Unfortunately, the antigen responsible for these interactions has yet to be elucidated.

Renal Involvement

Renal involvement in Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis is usually a consequence of inflammation and scarring of the aorta adjacent to the orifice of the renal artery, leading to stenosis of the renal artery and ischemic renal failure. One of the most common clinical presentations of this phenomenon is renovascular hypertension affecting more than 50% of patients with Takayasu arteritis. In Japan, Takayasu arteritis is an important cause of hypertension in adolescents.

Glomerular lesions and necrosis occurs in patients with large-vessel vasculitis, but this may be an overlap of a small-vessel vasculitis. Several cases of glomerulonephritis in the setting of Takayasu arteritis have been reported in the literature. The renal pathology in these cases varies from case to case, including focal segmental sclerosis, mesangial proliferation, membranoproliferative lesions, and crescentic lesions.

MEDIUM-SIZED VESSEL VASCULITIS: POLYARTERITIS NODOSA AND KAWASAKI DISEASE

The medium-sized vessel vasculitides are necrotizing arteritides that have a predilection for arteries that lead to major viscera and their initial branches. In the kidneys, the major targets are the interlobar and arcuate arteries, with less frequent involvement of the main renal artery and interlobular arteries (

Fig. 48.3). The two major categories of medium-sized vessel vasculitis are polyarteritis nodosa and Kawasaki disease. Pathologically, both are characterized in the acute phase by necrotizing arteritis with transmural inflammation that initially includes neutrophils and foci of fibrinoid necrosis (

Fig. 48.1). The acute necrotizing inflammation often erodes completely through the artery wall and into the adjacent perivascular tissue, thereby forming a pseudoaneurysm (

Fig. 48.4). Secondary complications of the arteritis include thrombosis, infarction, and hemorrhage. In only a few days, the lesions evolve from an acute neutrophil-rich inflammation to a “chronic” inflammation with predominantly mononuclear leukocytes. Sites of thrombosis and necrosis develop progressive scarring (

Fig. 48.2). By definition, medium-sized vessel vasculitides do not cause glomerulonephritis, although they can cause hematuria, proteinuria (usually less than 2 g per 24 hours), and renal insufficiency as a result of renal infarction. Pseudoaneurysms near the renal surface may rupture and cause severe, even fatal, retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal hemorrhage.

The meaning of the diagnostic term “polyarteritis nodosa” has evolved over the past century, and substantial confusion continues over how best to use it. The problem and the solution that we propose is best understood in historical context. Systemic necrotizing arteritis was first clearly described by Kussmaul and Maier in the mid-1800s.

39 They reported a patient with widespread visceral nodules caused by acute inflammation of arteries and called the process “periarteritis nodosa.” Ferrari introduced the term “polyarteritis nodosa,”

40 which is more appropriate because the inflammation is transmural rather than perivascular. For approximately 50 years, essentially all patients with any pattern of necrotizing arteritis were included in the polyarteritis nodosa category. During the early to mid-1900s, astute investigators recognized that many patients with necrotizing arteritis had distinctive distributions of vascular inflammation or characteristic pathologic processes that warranted their separation from patients with arteritis alone. For example, Kawasaki disease, GPA, EGPA, and MPA were initially included in the category of polyarteritis nodosa but now are recognized as distinct entities.

8 The removal of these vasculitides from the polyarteritis nodosa category is justified not only on the basis of different patterns and distributions of vessel involvement, but also because they have different natural histories, prognoses, and treatment requirements.

The reduction of polyarteritis nodosa to a more homogeneous and clinically useful category of vasculitis began when Arnaout, among others, recognized that some patients with necrotizing arteritis had lesions that could be seen only by microscopic examination.

41 Circa 1950, Zeek et al.

42,

43 and Godman and Churg

44 carried out careful evaluations of patients with arteritis and concluded that polyarteritis nodosa should be separated from the “microscopic” form of vasculitis that was characterized by involvement of not only small arteries but also venules and capillaries. As discussed later in the section on small-vessel vasculitis, Godman and Churg also concluded that polyarteritis nodosa was distinct not only from MPA but also from GPA and eosinophilic granulomatosis, and that MPA, GPA, and eosinophilic granulomatosis were related to one another.

The diagnostic approach that we advocate defines polyarteritis nodosa as necrotizing inflammation of medium-sized or small arteries without glomerulonephritis or vasculitis in arterioles, capillaries, or venules (

Table 48.2).

8 This allows the separation of polyarteritis nodosa from other types of vasculitis, such as GPA, MPA, and eosinophilic granulomatosis, which have necrotizing arteritis as a component of a systemic polyangiitis that affects capillaries, venules, and arteries. By using this approach, the presence of glomerulonephritis rules out a diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa and indicates the presence of some type of small-vessel vasculitis.

Table 48.3 compares some of the features of polyarteritis nodosa and MPA. Note that glomerular capillaritis (glomerulonephritis) or pulmonary alveolar capillaritis with pulmonary hemorrhage rule out a diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa and raise the possibility of MPA. Peripheral neuropathy is not a discriminator, because involvement of small epineural arteries in peripheral nerves may occur with polyarteritis nodosa or MPA. As discussed in more detail later, testing for ANCA is useful for distinguishing between polyarteritis nodosa and the ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitides.

45,

46,

47,

48,

49 In a patient with necrotizing arteritis, a positive ANCA result decreases the likelihood of polyarteritis nodosa and increases the likelihood of MPA, GPA, or eosinophilic granulomatosis (i.e., increases the likelihood that the patient has or will develop necrotizing inflammation of vessels other than arteries, such as pulmonary alveolar capillaritis or glomerular capillaritis [glomerulonephritis]).

Necrotizing arteritis that is pathologically indistinguishable from the necrotizing arteritis of polyarteritis nodosa can occur in patients with Kawasaki disease (

Figs. 48.1 and

48.3). Kawasaki disease is an acute self-limiting febrile illness, the second commonest vasculitis in childhood.

50 Kawasaki disease is characterized by the mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, which includes nonsuppurative lymphadenopathy, polymorphous erythematous rash, erythema of the oropharyngeal mucosa, erythema of the palms and soles, conjunctivitis, indurative edema, and desquamation of the extremities. A major cause for morbidity and mortality in patients with Kawasaki disease is the development of a necrotizing arteritis. This arteritis has a predilection for coronary arteries but can occur anywhere, including the kidney (

Figs. 48.1 and

48.3). Kawasaki disease is the most common cause of childhood-acquired heart disease.

50 Symptomatic renal involvement is rare in Kawasaki disease. Differentiation between the arteritis of Kawasaki disease and that of polyarteritis nodosa is very important because the treatment of Kawasaki disease differs from the treatment of polyarteritis nodosa (discussed in Treatment section).

The presence or absence of the mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome is an effective diagnostic discriminator between Kawasaki disease and polyarteritis nodosa.

Clinical Features

Patients with polyarteritis nodosa typically have constitutional symptoms, including fever and weight loss. The presence of mononeuritis multiplex, myalgias, and arthralgias, as well as skin lesions including nodules, ulcers, livedo reticularis, and digital ischemia in half of patients, characterize the disease. There is a spectrum of disease referred to as cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa associated with streptococcal infection.

50 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa has periodic exacerbations but is milder than classic polyarteritis nodosa. This presentation may be along the spectrum of systemic polyarteritis nodosa. Vasculitis of the coronary arteries may lead to cardiac symptoms. The renal disease seen in polyarteritis nodosa is primarily related to vasculitis of the renal arteries resulting in renovascular hypertension and/or renal parenchymal infarction. Patients with polyarteritis nodosa do not have evidence of small-vessel

vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, or pulmonary capillaritis. In fact, the lung is rarely injured in polyarteritis nodosa, in contrast to the frequency of pulmonary disease in patients with GPA, MPA, or EGPA. Although not distinguishing features, gastrointestinal complaints and peripheral neuropathy are more common among patients with polyarteritis nodosa than patients with MPA. The skin lesions of polyarteritis nodosa closely mimic cholesterol emboli and calciphylaxis and therefore histopathologic confirmation of diagnosis is required. The prognosis of polyarteritis nodosa is really a reflection of the involvement of the kidneys, heart, central nervous system, or gastrointestinal tract.

51Tc-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scanning of the kidneys can indirectly support the diagnosis of a medium-vessel vasculitis affecting the renal arteries by manifesting patchy areas of decreased isotope in the renal parenchyma.

52 Unquestionably, however, angiography of the renal, hepatic, and/or mesenteric vasculature via angiography is a superior approach for diagnosis of a medium vessel vasculitis. Demonstration of “aneurysms,” narrowing of arteries, or pruning of the peripheral vascular tree suggest medium-vessel vasculitis. Large pseudoaneurysms, stenosis of the renal arteries or large branches, and resultant areas of ischemia or infarct within the kidney can be demonstrated by magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography (CT) angiography.

Pathogenesis

The etiology of polyarteritis nodosa remains unclear, and most cases of polyarteritis nodosa are probably idiopathic. An association between polyarteritis nodosa and hepatitis B infection is evident by the fact that patients with hepatitis B antigenemia are at greater risk of developing polyarteritis nodosa. Hepatitis B virus has been implicated in up to one third of cases of polyarteritis nodosa.

54 A role for hepatitis B antigenemia in the pathogenesis of polyarteritis nodosa is further suggested by reports of vasculitis after hepatitis B vaccination.

55 Furthermore, treatment with antiviral agents and plasma exchange has led to resolution of the vasculitis in patients whose serology converts from being positive for the HBe or HBs antigens to the corresponding antibodies.

56,

57Polyarteritis nodosa has been associated with a number of cancers, especially hairy cell leukemia.

58 Treatment of hairy cell leukemia with interferon-alpha (INF-

α) may be associated with resolution of polyarteritis nodosa.

59 As opposed to patients with small-vessel vasculitis, patients with polyarteritis nodosa are ANCA-negative.

60

Renal Manifestations

Both polyarteritis nodosa and Kawasaki disease are medium-sized vessel vasculitides that affect the kidney. These arteritides result in necrotizing lesions in the major renal arteries and aneurysm formation with thrombosis and renal infarction. The aneurysms are not true aneurysms but rather pseudoaneurysms. The arteritis of Kawasaki disease most commonly involves the coronary arteries, but in at least 25% of patients the lesions also involve the kidney. Tubulointerstitial nephritis is a not uncommon renal presentation in Kawasaki disease.

50 Renal manifestations of Kawasaki disease can lead to renal failure. Kawasaki disease is distinguished from polyarteritis nodosa by the pathognomonic sine qua non feature of mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. Renal arterial involvement by polyarteritis nodosa, including interlobar and arcuate arteries, results in renal ischemia, infarction, and hemorrhage. One of the most painful and catastrophic consequences of this disease is rupture of an arterial pseudoaneurysm that causes retroperitoneal and sometimes intraperitoneal hemorrhage.

Outcome

Most studies examining patient outcome and predictors of patient survival in polyarteritis nodosa antedate the Chapel Hill consensus conference of 1994. These studies are based on cohorts of patients that include those with MPA, EGPA, and hepatitis B-associated classic polyarteritis nodosa. Earlier studies report a 5-year survival rate of approximately 55% in patients primarily treated with corticosteroids alone.

75 The addition of cyclophosphamide or immunosuppressive therapy to glucocorticoids seems to have improved the 5-year survival rate to about 80%. Patients with bowel infarction, serious gastrointestinal bleeding, or renal insufficiency had particularly poor prognosis. In a more recent prospective study including 342 patients, of whom 119 had classic polyarteritis nodosa without HBV (89 patients with HBV, 52 patients with MPA, 82 patients with EGPA),

51 proteinuria of 10 g per day, renal insufficiency, and gastrointestinal tract involvement were the major prognostic markers for a worse outcome.