(1)

Al Agouza, Cairo, PO, Egypt

12.1 Vaginal Atresia (VA)

The vagina originates from two embryonic structures: the upper part from Müllerian duct system and the lower third from the urogenital sinus. Canalization of the vaginal canal is complete by the 20th week. Misdevelopment presented as failure of fusion or canalization of these two systems in vertical plane may be clinically present with a spectrum of Müllerian duct anomalies. Vaginal atresia (VA) is one of them, where the missing portion of the vagina is replaced with fibrous tissue.

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) classification of Müllerian duct anomalies in 1998, vaginal atresia is categorized as Type IA (this will be discussed with uterine anomalies). Some authors believe that variants of VA, formerly called partial vaginal agenesis, are more correctly classified as variants of a transverse vaginal septum (discussed with hymenal anomalies).

In VA the appearance of the external genitalia can be normal or the vulva slightly retracted upward. This is why this abnormality cannot be detected without a careful examination of the genitalia.

Incidence

Vaginal atresia is a rare condition. It occurs in 1:4,000 to 1:10,000 females, and the prevalence of Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome has been reported at 1 in 4,000 to 1 in 5,000 live births [1].

Etiology

Most of the cases of vaginal atresia reported are syndromic; a lot of syndromes had vaginal atresia as a main manifestation; complete vaginal agenesis is discovered in 75 % of patients with Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome, which is a rare developmental failure of Müllerian ducts (described by Mayer in 1829) [2], with uterine anomalies (described by Rokitansky in 1838 and Kuster in 19103) [3]; it is defined as Müllerian aplasia with vaginal agenesis and uterine remnants; the patient karyotype is 46 XX. Approximately 25 % of patients have a short vaginal pouch. Some girls may have rudimentary uterine horns. The ovaries are normal, and the fallopian tubes are usually present. It is commonly associated with renal and sometimes vertebral and other skeletal anomalies. Others syndromes include Bardet–Biedl syndrome, Fraser syndrome, and Winter syndrome [4].

Clinically

Clinical findings vary depending on the anatomy of the vaginal outlet and the changes in the upper vagina and uterus. The upper vagina becomes enormously distended when the girl starts to menstruate, usually producing a palpable abdominal mass arising from the pelvis. The fallopian tubes can be normal, although they may be distended allowing escape of the fluid into the peritoneum. Other anomalies are occasionally seen with hydrometrocolpos.

The majority of the cases represented for the first time are usually with hydro- or hematocolpos.

The differential diagnosis of vaginal agenesis includes transverse vaginal septum, cervical agenesis, and androgen insensitivity syndrome (Figs. 12.1 and 12.2).

Fig. 12.1

A case of vaginal atresia with adrenogenital hyperplasia

Fig. 12.2

Vaginal atresia in adolescent girl without AGH

The diagnosis is usually made when symptoms of obstruction are obvious. Ultrasound, abdominal and endorectal, and other imaging studies confirm the physical examination. Urogram would demonstrate anterior and superior displacement of the bladder and, possibly, hydronephrosis and hydroureter. As Müllerian agenesis can be associated with other anomalies, particularly those of the kidneys and skeleton, further investigations are indicated. MRI is usually needed for confirmation of the uterovaginal anomalies and ovarian evaluation. In the laparoscopy, a fibrous tract or two solid rudimentary horns are generally observed.

Treatment

Therapy is directed to relieve the obstruction of the vaginal outlet and provide normal sexual life and reproductive function. Vaginal reconstruction is required, sometimes by an abdominoperineal approach, but stenosis and fistula formation could complicate the postoperative period.

In overview, the first therapy is time consuming but nonsurgical and requires the use of progressive vaginal dilators [5]. Surgical reconstruction of the vagina has many variations. The operations, for the most part, develop the potential space between the bladder and the rectum and replaced this space with a stent utilizing tissue, most commonly a split-thickness skin graft or synthetic materials. The latter procedure, developed by Abbe-McIndoe [6], is easy to perform but must be done only when the patient will use the vagina frequently. An alternative procedure, to build a neovagina, was devised by Williams. This procedure utilizes labial skin and results in a vaginal pouch whose axis is directly posterior. Other options include utilizing free skin graft over a mold and inserting it in a space created between the bladder and rectum (Figs. 12.3 and 12.4).

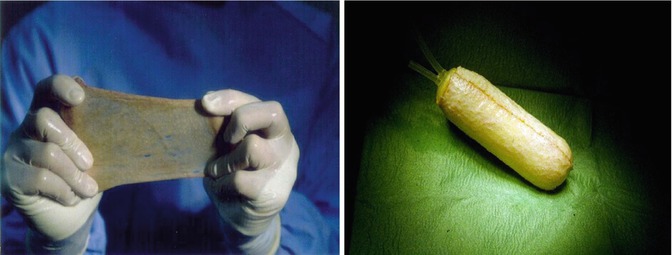

Figs. 12.3 and 12.4

Vaginoplasty by free skin graft and vaginal tube reconstructed over a mold

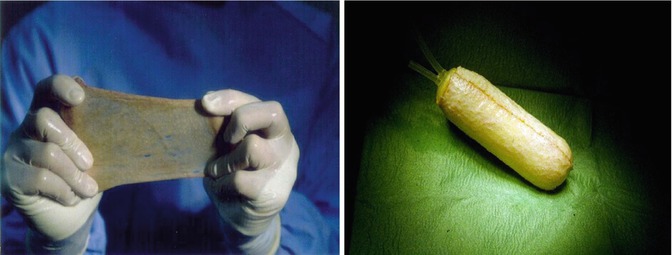

Also intestinal vaginoplasty is recently advocated with the use of sigmoid colonic pedicle graft with satisfactory results in different age groups [7] (Fig. 12.5).

Fig. 12.5

Vaginal reconstruction from sigmoid colonic graft

Vecchietti [8] developed a laparoscopic procedure for producing a neovagina. Sutures are placed laparoscopically in the peritoneal folds between the bladder and rudimentary uterus causing invagination over the course of 7–9 days.

12.2 Vaginal Polyps

Nomenclature

Vaginal adenosis

Vaginal polyps are very rare lesions especially in young girls. Most of them are fibroepithelial (stromal) polyps whose histological diagnosis is usually straightforward. A variety of other mesenchymal, epithelial, or mixed lesions may present as a polypoid mass of the vagina; these lesions include leiomyoma, superficial myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract, rhabdomyoma, and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (sarcoma botryoides).

Incidence

Vaginal polyps are very rare tumors with a polypoid or pedunculated appearance and not only may raise the specter of sarcoma botryoides in the clinician’s mind but also may have bizarre histological features suggesting malignancy, compounding the clinical confusion.

Etiology

There are several theories regarding the histogenesis of the tubulo-squamous vaginal polyp. The Müllerian and Wolffian origin as well as the origin from the urogenital sinus or from vaginal adenosis was hypothesized. Other possible theories include the derivation from mesonephric remnants or misplaced Skene’s glands. This theory is supported by the fact that some of the reported cases showed PSA and PSAP positivity. Müllerian elements invade the sinovaginal bulb [9].

It is possible that edematous polyps in newborn infants are a reflection of intrauterine hormonal stimuli, just as edema of the vulva [10]. Vaginal polyps are rare tumors with a polypoid or pedunculated appearance and not only may raise the specter of sarcoma botryoides in the clinician’s mind but also may have bizarre histological features suggesting malignancy, compounding the clinical confusion.

12.3 Vaginal Sarcoma Botryoides

Nomenclature

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the vagina, botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma

Definition

Sarcoma botryoides is a subtype of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma that can be observed in the walls of hollow, mucosa-lined structures such as the nasopharynx, common bile duct, urinary bladder of infants and young children, or vagina in females, typically younger than age 8.

Historical Background

The term botryoides (means shaped like a bunch of grapes) was first used by Pfannenstiel in 1892, although this case was first reported by Weber in 1867 [12].

Incidence

It is one of the most common soft tissue tumors in children. After the head and neck, vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma is the second most common site for embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma [13].

Clinical Picture

Sarcoma botryoides is a polypoid form of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, usually present with vaginal bleeding, discharge, and the appearance of a hemorrhagic grapelike mass protruding from the vaginal introitus. The anterior vaginal wall is more commonly involved than the posterior. Very few cases had been reported to originate from the cervix in young age, but this is not the case in older females. The tumor infiltrates widely under the intact vaginal epithelium and later invades the vesicovaginal or rectovaginal septa to involve the bladder or less commonly the rectum producing sometimes a fistulous tract (Figs. 12.7 and 12.8).

Fig. 12.7

A typical case of vaginal sarcoma botryoides

Fig. 12.8

Advanced and ulcerated case of vaginal sarcoma botryoides

Microscopically, the edematous myxomatous stroma contains pleomorphic cells; larger multinucleated cells with striated fibrils in the cytoplasm can be found in most tumors, and this has led to the conclusion that these tumors are embryonal rhabdomyosarcomata rather than mixed mesodermal tumors of Müllerian duct origin as considered previously. Differential diagnosis has been directed to a similar appearing benign tumor, the vaginal polyp. The role of ultrasound is to:

Define the origin of the mass.

Note any complications such as hydrocolpos.

Detect local nodal spread.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree