(1)

Al Agouza, Cairo, PO, Egypt

7.1 Embryology and Anatomy

Two distinct embryological pathways are suggested for the development of the distal glanular urethra. One theory supports the idea that fusion of the urethral folds extends all the way to the tip of the glans. It has been suggested that the entire penile urethra might differentiate from the fusion of the urethral plate via the mechanism of epithelial–mesenchymal interactions. Another hypothesis suggests that a solid ectodermal ingrowth of epidermis canalizes the glanular urethra (the fusion of urethral folds proximally and the ingrowth of ectodermal cells distally).

During the development of the phallic part of the urogenital sinus, the urethral plate tubularizes by midline meeting of its elongated folds. Simultaneously, the outer ectodermal genital folds fuse at the midline, which is demarcated by the perineal and penile raphe. As the proximal urethral folds close, a solid core of ectodermal tissue penetrates the glans of the penis to join the anterior urethral component. The contiguous walls of this ectodermal ingrowth and the newly tubularized urethra break down to establish urethral continuity. This natural anastomosis leads to the development of the fossa navicularis.

The male urethra may be subdivided into the anterior and posterior urethra. Starting at the bladder neck, the posterior urethra is lined with transitional epithelium and consists of the prostatic urethra and the membranous urethra. The prostatic urethra is characterized by the orifices of numerous prostatic ductules and by the verumontanum or seminal collicle at its posterior aspect. The latter represents a small mound that carries the orifices of the ejaculatory ducts at its lateral aspects and the prostatic utricle as a blindly ending diverticulum in its center. The membranous urethra crosses through the urogenital diaphragm, to connect the intracorporal part of the urethra to the extracorporal or anterior part. The anterior urethra, in turn, is lined with squamous cell epithelium and completely surrounded by the corpus spongiosum. It divides into the bulbous urethra and the pendulous urethra. The bulbous urethra is characterized by its covering by the bulbocavernosus muscle inferiorly and by the openings of the bulbourethral or Cowper’s gland ducts. Cowper’s glands are up to 4.5 cm long. In addition, numerous small lacunar Littre’s glands open into the anterior urethra. At the distal end of the urethra, close to its orifice, the navicular fossa represents a bulbous dilation of about 1 cm in length.

For imaging of the male urethra, conventional radiographic contrast studies including retrograde urethrography are most commonly utilized. They are best suited for delineating luminal abnormalities of the urethra and thus are commonly used as the primary imaging modality for patients with various urethral abnormalities such as trauma, inflammation, and stricture. More recently, the cross-sectional imaging techniques of ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging have been utilized increasingly for urethral and periurethral abnormalities. These studies are most valuable as an adjunctive tool in patients with the complex anatomical derangements such as congenital anomalies and posterior (or bulbomembranous) urethral injuries. These cross-sectional techniques can be performed during micturition or with retrograde injection of saline or jelly through the urethral meatus to improve visualization of the urethral luminal abnormalities [1].

7.2 Variant of Hypospadias

1.

Chordee without hypospadias (CWH)

2.

Megameatus intact prepuce hypospadias variant

Hypospadias is a developmental anomaly in which the urethra opens on the ventral side of the penis. It is the most common congenital defect of the genitalia and is often missed on prenatal ultrasound examination. It is a cause of concern and psychological trauma for the child and the parents. The estimated incidence of this malformation is between 0.2 and 4.1 per 1,000 live births, with wide variation from country to country, a greater frequency of hypospadias has uniformly been found in Caucasians than in other races, and birth defect surveillance systems reported transient 1.5- to 2-folds increases in the prevalence of hypospadias in Norway.

Historical Background

The earliest medical text describing hypospadias dates back to the second century AD and was the work of Galen, the first to use the term. During the first millennium, the primary treatment for hypospadias was amputation of the penis distal to the meatus [2].

The location of the abnormal urethral meatus classifies the hypospadias. Although several different classifications have been described, most physicians use the classification that was proposed by Barcat and modified by Duckett, which describes the location of the meatus after correction of any associated chordee [3].

As hypospadias is a common anomaly it will not be discussed, only its variants will be illustrated.

7.2.1 Chordee Without Hypospadias (CWH)

Definition

The term chordee means “curvature”; it was introduced into medical literature in the seventeenth century from the French in relation to gonorrhea. It was defined as a “painful downward curvature of the penis due to inflammation,” and commonly the term chordee without hypospadias (CWH) is used when the meatus is located at the tip of the glans penis, yet the prepuce is distorted, and ventral penile curvature is associated with abnormalities of the fascial tissues, corpus spongiosum, or both [4] (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1

Penile chordee without hypospadias resulting in ventral bent

Nomenclature

Penile bent, congenital ventral penile curvature, and congenital penile angulation

Incidence

Isolated CWH is a rare entity, which comprises 4–10 % of all congenital chordee, since a chordee is an iatrogenic anomaly that results from the failure of proper surgical repairs. The estimated prevalence of congenital chordee in all population is about 0.4/1,000 [5].

Historical Background

The major significance of chordee was fully appreciated by Galen in the second century AD and then almost forgotten until Mettauer in 1842. Who suggested multiple subcutaneous incisions to straighten chordee, but this entity was first described by Siever in 1962, and since then, various classifications were advocated for it [6].

Etiology

The precise etiology of congenital chordee has not been elucidated to date, although it is now well accepted that varied anatomical changes are related to chordee with and without hypospadias and various surgical procedures are required. It was advocated that chordee was due to a congenitally short urethra and that the urethra should be transected, but years later Devine and Horton raised their theory that chordee without hypospadias resulted from dysgenesis of fascia surrounding the urethra [7].

Three major theories are proposed for the cause of penile curvature:

Abnormal development of the urethral plate

Abnormal, fibrotic mesenchymal tissue at the urethral meatus

Corporal disproportion or differential growth of normal dorsal corpora cavernosa tissue and abnormal corporal tissue ventrally

Classification

The most widely accepted one is also modified by Devine and Horton [7]; they classified chordee into three groups according to the layers affected, namely:

Kramer et al. on 1982 [8] found that corporal disproportion was another principal cause of chordee, and they classified this condition as group IV chordee without hypospadias.

Dorsal or lateral curvatures of the penis, both with and without hypospadias, have also been described Chap. 2.

Management

It may be possible to achieve good correction by degloving the shaft and excising chordee tissue while preserving an intact urethra. At the time of operation, however, it may prove necessary to excise the abnormal urethra back to a healthy spongiosum-supported urethra and proceed to urethroplasty as if it were the corresponding degree of true hypospadias. Surgery should be recommended for this patient primarily because the penis is visibly bent and the urethra is basically only a thin tube. Correction of significant chordee in this setting may involve creation of hypospadias to straighten the penis. The hypospadias must then be repaired in the same or a second operation. In other instances, the bent part of the erectile portions of the penis must be plicated with permanent sutures in order to straighten the penis [9].

Other Variations of Chordee

Penile torsion (wandering raphe) consists of a counterclockwise rotation of the penis. It may be referred to as “wandering raphe” because the midline raphe of the penis may wrap around the penis in a counterclockwise fashion. When the raphe approaches 90°, there may be penile torsion underneath the foreskin. Penile torsion by itself is not usually corrected unless it approaches 90°. Penile torsion may also be seen in association with hypospadias and may be improved to varying degrees in the course of hypospadias repair.

7.2.2 Megameatus Intact Prepuce (MIP) Hypospadias Variant

Nomenclatures

Dorsal preputial hood, hypospadias hidden by a complete prepuce

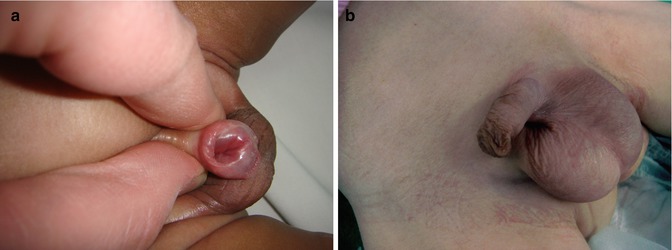

There are several differences between MIP and typical distal hypospadias; obviously MIP by definition is associated with a completely formed prepuce in contrast to the ventrally deficient foreskin in other cases of hypospadias, and furthermore, the meatus is abundantly large in the MIP variant, whereas many boys with distal hypospadias have a rather small-appearing meatus (Fig. 7.4). Ventral curvature is much less likely to occur in a patient with MIP than in those with other varieties of distal hypospadias. Correction basically involves tubularization of the urethral plate to move the meatus to the glans tip. Because the urethral plate is larger than usual in these boys, a relaxing incision is not generally needed as with TIP repair, although, when the plate is flat, incision will help “hinge” it to create a vertical and slit meatus. Some patients have a transverse web of skin distal to the meatus, and this should be excised to prevent deflection of the urinary stream. Care must be exercised when separating the glans wings from the urethral plate, since the plate in MIP patients sometimes extends more laterally than is usual in routine distal hypospadias patients.

Figs. 7.4, 7.5, and 7.6

Megameatus intact prepuce hypospadias variant

It is important to recognize that this is not the result of a “botched” circumcision. These boys have a normal-appearing penis, and so the defect is not encountered until the foreskin becomes retractable or circumcision is performed (Figs. 7.5 and 7.6).

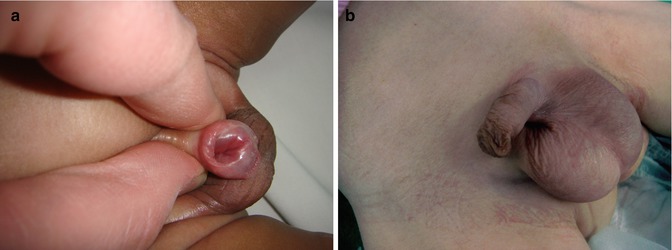

Because there is no external clue to the presence of this variant, it sometimes comes to light for the first time in a boy who is about to undergo circumcision. In this situation, the planned circumcision should be abandoned, the child returned to the ward, and the findings discussed with the parents (Fig. 7.7).

Fig. 7.7

(a, b) Hypospadias hidden by a complete prepuce

7.3 Epispadias

Incidence

Isolated epispadias without exstrophy is a rare anomaly, the incidence being 1 in 120,000 in males; the male-to-female ratio is 2.3:1 [10].

Historical Background

The first recorded case of epispadias is attributed to the Byzantine emperor Heraclius for his unknown disease. Isolated epispadias remained unknown and untreated until it was described by Morgagni in 1761. The initial attempts to treat this anomaly were restricted to controlling the incontinence. In 1869, Karl Thiersch described the etiology and anatomy of epispadias and reported on a case of epispadias reconstruction with a long-term follow-up of 11 years [11].

Definition

In primary penile epispadias, there is variable diastasis that tends to be less severe than in bladder exstrophy. The pelvic ring is often complete, with an apparently normal abdominal wall. The extent of the defect can vary from a mild glandular defect to complete defects as are observed in bladder exstrophy, diastasis of the pubic bones, or both. Simple epispadias occurs less commonly than the more severe form associated with exstrophy of the bladder. As a result the anus is appropriately sited and the scrotum also appears normal. The urethra opens on the dorsal aspect of the penis (Fig. 7.8).

Fig. 7.8

Male epispadias involving the whole penile urethra

Classification

Depending on the severity of the epispadias, the urethra may open distally on the glans (glanular epispadias), on the shaft (penile epispadias), or proximally at the junction with the anterior abdominal wall (pubic or penopubic epispadias). The penopubic type is the first being most frequent. Urinary incontinence is frequently observed with penopubic epispadias and occasionally with penile type, but it is not associated with glanular epispadias; underlying deficiencies of the bladder neck and proximal urethra and striated sphincter complex determine the degree of associated incontinence. In these cases, the posterior urethra merges with the bladder neck, and the verumontanum may lie at the level of the bladder neck or even within the bladder itself. The ureteral orifices often lie close together and are normal or narrowed in caliber, contrasting with the wide refluxing orifices seen in exstrophy.

In males, epispadias causes impotence, which results from the dorsal curvature of the penile shaft and incomplete urethra. Also reported are frequent ascending infections to the prostate or bladder and kidneys and psychological problems related to the deformity.

Etiology

Unlike hypospadias, epispadias can be explained by defective migration of the paired primordia of the genital tubercle that fuse on the midline to form the genital tubercle at the fifth week of embryological development. Epispadias and exstrophy of the bladder are considered varying degrees of a single disorder. Another hypothesis relates the defect to the abnormal development of the cloacal membrane.

Associated Anomalies

Associated congenital anomalies include diastasis of the pubic symphysis, bladder exstrophy, renal agenesis, and ectopic pelvic kidney, duplication of urethra is not rare with epispadias, and sometimes the child may have a normally positioned urethra and an epispadiac duplicated system with variable extent (Fig. 7.9) Chap. 7.5.

Fig. 7.9

Epispadias with an associated urethral duplication

Management

The treatment of this anomaly is far from trivial and repair can be challenging. There are two popular surgical techniques described well in the literature with their pros and cons: the first is the modified Cantwell technique [12], which involves partial disassembly of the penis and placement of the urethra in a more normal position, and the second and most recent evolution is the complete penile disassembly. The drawback of modified Ransley techniques is persistence of short penile length and residual dorsal chordee that is likely to be eliminated in complete penile disassembly. The major disadvantages of the Mitchell technique for epispadias repair are the necessity for aggressive dissection and occasional resultant of hypospadias meatus that require second-stage urethroplasty. This is because the urethral plate is usually shorter than the corpora cavernosa [13]. Correction of glandular epispadias with reposition of the distal urethra and creation of a symmetric glans (glanuloplasty) is indicated in childhood or adolescence at the patient’s request for cosmetic or psychological reasons.

Penile epispadias is corrected in childhood with penile straightening by resection of the chordee and creation of a new urethra of adequate caliber and length urethroplasty.

7.3.1 Female Epispadias

Female epispadias is a rare abnormality, not commonly recognized by most practitioners. The diagnosis is supported by a history of urinary incontinence and physical findings of bifid clitoris and patulous urethra. The condition can have serious physical and psychological consequences leading to a gross disruption of social function later on at adulthood (Fig. 7.10).

Fig. 7.10

Female epispadias

Incidence

Isolated epispadias without exstrophy is a rare anomaly, the incidence being 1 in 448,000 in female; it is 3–4 times less common than in males; patients with isolated epispadias present with various degrees of abnormalities [14].

Classification

A classification by Davis described three degrees of epispadias in female patients [15]:

In the mildest degree, the urethral meatus simply appears patulous.

In the intermediate degree, the urethra is dorsally split along most of the urethra.

Finally, in the most severe degree of epispadias, the urethral cleft involves the entire length of the urethra and sphincteric mechanism, and the patient is rendered incontinent.

The ureterovesical junction is inherently deficient in cases of epispadias. The incidence of reflux is reported to be 30–75 % [16].

Etiology

There is no evidence of a single-gene defect or common environmental factor associated with this syndrome. Possible reported associations include Caucasian race, advanced parental age, birth order, and in vitro fertilization. Most cases occur sporadically; however, to date, 23 families having at least two affected members have also been reported. There are also 28 reported cases of twin pairs.

In females, epispadias and normal genitalia appearance can be restored during adolescence.

7.4 Megalourethra

Congenital megalourethra is a rare form of functional obstructive uropathy caused by dysgenesis of the penile corpora cavernosa and spongiosa which results in extensive dilation of the penile urethra; it has been postulated that it may be caused by abnormal development or hypoplasia of the penile erectile tissue, secondary to distal urethral obstruction.

Incidence

Megalourethra is a very rare congenital anomaly of the male urethra with about 100 cases being reported till 2011 [22].

Historical Background

The first case of congenital megalourethra was reported by Obrinsky, in 1949, who also described its association with “prune-belly” syndrome, which been described subsequently by others [17]. Benacerraf et al., in 1989, were the first to report this condition prenatally, and so far only a handful of cases have been reported [18]. Techniques of surgical repair of the scaphoid megalourethra were first published by Nesbit and Baum more than 50 years ago [19].

Etiology

1.

Failure of urethral recanalization as a cause of megalourethra.

2.

Temporary obstruction during early development may be an etiologic factor in fusiform type

3.

Failure of development of erectile tissue may be an etiologic factor in scaphoid type

4.

Abnormal mesodermal development: developmental arrest of the mesenchymal elements of the penis would lead to severe laxity and defective development of the erectile tissue

The pathogenesis of the prune-belly syndrome (PBS) remains controversial but two theories predominate. The first theory supports an obstructive phenomenon early in gestation leading to irreversible damage to the genitourinary tract and abdominal wall. The second theory suggests mesodermal injury between the sixth and tenth weeks of gestation as the primary abnormality [20].

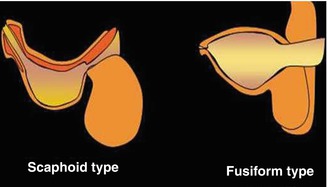

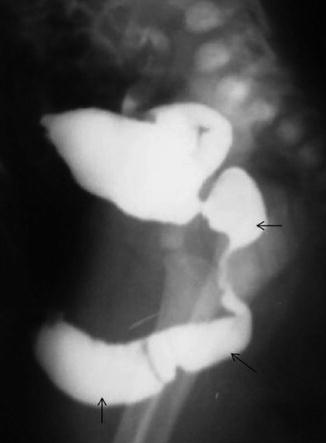

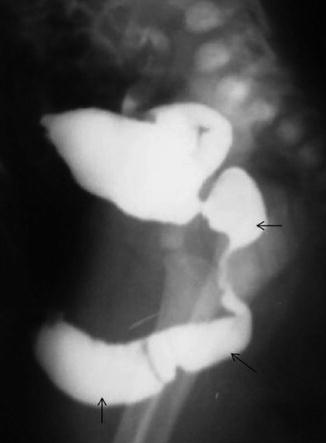

Classification

Based on the findings at urethrography, Dorairajan described two variants: scaphoid and fusiform. Babies with the scaphoid type were found to have hypoplasia of the corpus spongiosum, with bulging of the ventral urethra. Those with the fusiform variant were found to have a deficiency of both corpora spongiosa and cavernosa, with circumferential expansion of the urethra [21] (Fig. 7.11).

Fig. 7.11

Diagram of the types of megalourethra

However, this classification is neither pathological nor etiologic and does not help in prognostication, so another classification of this condition recently suggested by Amsalem et al. in 2011 [22] to:

(a)

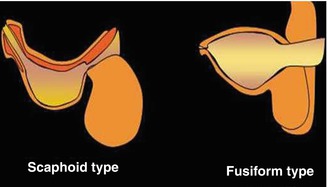

Primary (or ex-vacuo), caused by absence or hypoplasia of the corpora spongiosa and cavernosa, associated with normal amniotic fluid volume, usually preserved renal function and better outcome (Figs. 7.12 and 7.13).

Fig. 7.12

Scaphoid megalourethra

Fig. 7.13

Fusiform megalourethra with dilation of the prostatic urethra

(b)

Obstructive (secondary), which results in oligohydramnios with a higher incidence of renal failure, pulmonary hypoplasia, and thus mortality. In both types, the corpora are hypoplastic (either secondary to pressure in the obstructive type or the result of an initial absence of the corporal tissue in the primary type). The “primary” type can become obstructive if blocked by debris and can result in oligohydramnios later in gestation (Fig. 7.14).

Fig. 7.14

Primary type can become obstructive with a visible debris coming from the meatus

It has been postulated that isolated megalourethra represents a severe form of the “prune-belly” triad caused by a common initial insult (e.g., distal urethral obstruction) and resulting in abdominal distention and thus decreased development of the abdominal wall musculature (Fig. 7.15).

Fig. 7.15

Fusiform megalourethra

Recently, Sepulveda et al. [23] published the only series of cases diagnosed prenatally, of which one was terminated and three were live born. All of these cases were complicated by late-onset oligohydramnios and neonatal death due to pulmonary hypoplasia (Fig. 7.16).

Fig. 7.16

Megalourethra antenatally diagnosed at the 2nd trimester

The mortality is 13 % in the “primary/scaphoid” type and 66 % in the “secondary/fusiform” type; in babies that were live born, the main morbidities complicating in postnatal life did not differ from those of cases with lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO), regardless of the etiology: pulmonary hypoplasia due to oligohydramnios, which can result in death, and chronic progressive renal failure, which can result in end-stage renal disease. In megalourethra, further morbidity specific to the condition includes urethral dysfunction (voiding and possible erectile).

Management

Megalourethra should be considered in all male fetuses presenting prenatally with megacystis, and detailed fetal ultrasonography should look for an elongated and/or distended phallic structure as well as any associated anomalies. Techniques of surgical repair of the scaphoid megalourethra were first published by Nesbit and Baum more than 50 years ago, and the procedure is still currently in use with some modification. It involves the full-length degloving of the penile shaft, followed by a reconstruction of the neourethra over an appropriate-sized catheter after excising the redundant urethra. Excessive skin is also excised and the edges are reapproximated.

Proximal urinary diversion is optional. Recently, an alternative approach which involves staged correction has been proposed. In the first stage, marsupialization of the megalourethra is done ventrally to prevent stasis, bacterial colonization, and infection. This is followed by closure of the defect when the child grows older. The prognosis in the fusiform variety is poor, and since all the corpora are affected, the chances of creating a functional phallus are minimal. These patients may benefit from penile reconstruction at a later date.

However, urologic repair is almost impossible when there is a lack of supportive corporal tissue, although successful cosmetic and functional repairs have been reported. This technical difficulty has even led some urologists to suggest early sex reassignment to female.

Antenatally detected cases could be managed by fetal bladder shunting (vesico-amniotic) to overcome the functional urinary obstruction which had been tried with limited success. However, unlike other causes of LUTO, patients with megalourethra also suffer from dysfunction in urination and probably erection and ejaculation, and all live children in series had several urologic procedures. So the goal of early prenatal diagnosis of this condition is to provide parents with an accurate diagnosis and prognosis, thus allowing them to make an informed decision regarding continuing or terminating the pregnancy [23].

7.5 Urethral Duplication

Nomenclature

Accessory urethra

Definition

Urethral duplication is a rare congenital anomaly, affecting mainly boys, with a variable clinical presentation because of the different anatomical patterns. This pathological condition may be easily underdiagnosed, especially in patients with other associated anomalies, such as hypospadias or bladder exstrophy.

These accessory channels most often are present as primarily dorsal or ventral in the sagittal plane, and collateral or side-by-side duplications are rare (Fig. 7.17).

Fig. 7.17

Duplicated urethra with double streams

Incidence

Urethral duplication is rare so far; about 300 cases have been reported in the literature; this anomaly is most common in males with few cases reported in females [25].

Etiology

Embryology of urethral duplication is unclear; however, to our knowledge, no single theory explains all of the various types of anomalies, and a lot of hypotheses have been proposed, including ischemia, abnormal Müllerian duct termination, growth failure of the urogenital sinus, and also misalignment of the termination of the cloacal membrane with the genital tubercle [26].

Diagnosis

The clinical significance of urethral duplication is various. Patients affected by this anomaly can present with a double stream, incontinence, outflow obstruction, and recurrent urinary infection or be totally asymptomatic. A proper clinical examination, voiding cystourethrography, retrograde urography, urethrocystoscopy, and intravenous urography (in selected cases) will give a clear picture of the anomaly. The child’s urinary stream must be carefully assessed to determine its location and character, based on the findings with reference to adequacy of channel, position of verumontanum and prostatic bundle in the cases of posterior urethra involvement, abnormality of location, and symptoms,

Classification

Urethral duplication is classified into the following types:

Type I: blind and incomplete duplication

Type IIA: complete patent duplication, with two meatuses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree