(1)

Al Agouza, Cairo, PO, Egypt

5.1 Testicular Development

During the seventh week, XY male gonads begin to differentiate under the influence of a series of testis-determining genes. The first to be expressed is SRY, the key gene on the Y chromosome controlling male differentiation. SRY expression depends on the WT1 transcription factor. SRY initiates the development of Sertoli cells by indirectly (perhaps by altering chromatin structure) or directly increasing expression of SOX9, a related transcription factor encoded not on the Y chromosome but on chromosome 17. SOX9 expression also requires an intermediate level of expression of the transcription factor DAX1 but is inhibited by high DAX1 levels.

Sertoli cells surround germ cells to form testis cords, which nourish primordial germ cells and direct them into the pathway for male gametogenesis. In the testes, germ cells (before spermatogonia) undergo mitotic arrest and are blocked from entering meiosis until after birth. Sertoli cells secrete several possibly redundant factors that induce migration of additional cells from the mesonephros into the testis, and they also stimulate proliferation of cells in the coelomic epithelium. These may include nerve growth factors, hepatocyte growth factor, platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factors (FGF), particularly FGF9. Recruitment of additional endothelial cells leads to development of a testis-specific vasculature that is required for development of the normal organization of the testis.

Steroidogenic cells develop from the mesonephros, a process requiring the SF1 transcription factor, and these cells migrate into the developing adrenal cortex and testis at about 8 weeks’ gestation. In the testis, they become Leydig cells, which secrete the testosterone required for the subsequent development of the male reproductive system. Other factors required for Leydig cell differentiation and growth include DHH (desert hedgehog) and PDGFA (“A” being the first of four ligands termed A to D) secreted by Sertoli cells, as well as the ARX transcription factor expressed in interstitial cells surrounding the testis cords. In the first trimester, testosterone secretion is mainly under the control of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), whereas it subsequently requires luteinizing hormone (LH) secreted by the fetal anterior pituitary gland.

5.2 Variant of Undescended Testicle

5.2.1 Ascending Testis

Nomenclature

Acquired undescended testicle, testis migrans

The term ascending testis is applied to two clinical conditions:

1.

Primary ascending testis

2.

Secondary ascending testis (post herniotomy or hydrocelectomy)

Incidence

The prevalence of acquired UDT for 6‐year-, 9‐year-, and 13‐year-olds is, respectively, 1.2, 2.2, and 1.1 %, and the incidence in babies with Down syndrome is 4.35 % [1].

Agarwal and colleagues have presented results from the first longitudinal study of retractile testes in the USA; they showed that the retractile testis has a significant risk (32 %) of becoming an ascending testis; however, other studies report much less incidence, 2 % [2].

The incidence of secondary ascending testis (postoperative testicular ascent) is 0.8–2.8 % in boys who undergo surgery for inguinal hernia [3].

Etiology

Primary Ascending Testis

The etiology of primary ascending testis is unclear, but there are two different explanations:

1.

Mechanical tethering due to a patent processus vaginalis or fibrous strings deep in the cremaster muscle and spermatic fascia (remnants of obliterated processus vaginalis), which limits the growth and elongation of the spermatic cord during somatic growth [4].

Atwel explained that the peritoneum of the processus vaginalis becomes partially absorbed into the parietal peritoneum which leads to traction on the spermatic cord consequent to testicular ascent [5].

Also, the fibrous string containing a partially patent processus vaginalis is not unique to the ascending testis; similar findings may be observed at least in some cases, during surgical procedures for congenital hydrocele.

2.

Low-lying undescended testis: another explanation of testicular ascent is perhaps the increased elasticity of tissues in infants and young boys makes some low-lying undescended testes initially appear to be merely retractile testes.

Histopathological studies of ascending testis support the notion that this condition is a late manifestation of a low form of primary cryptorchidism. No difference was found in the total number of germ cells per tubule or the differential germ cell count in the ascending and contralateral descended testis compared to age- and position-matched controls with cryptorchidism [6].

Secondary Ascending Testis

Secondary ascending testes are thought to be normally developed intrascrotal testes that become trapped in scar tissue after groin surgery and subsequently tethered in an abnormal position above the scrotum.

Postoperative ascent occurs in testes that are actually low-lying undescended testes manifested by surgery. A histopathological study showed that there was no difference between biopsies obtained from postoperative ascending testes and those obtained from undescended testis (Figs. 5.1 and 5.2).

Fig. 5.1

Ascending testis after orchidopexy

Fig. 5.2

Ascending testis after orchidopexy

Clinical Picture

The ascending testis may be difficult to diagnose in small boys.

It has proposed criteria to differentiate an incompletely descended testis from a retractile testis: (1) Incompletely descended testes are smaller than the contralateral gonad. (2) The testis rapidly retracts out of the scrotum when the testis is released. (3) Pain is elicited when the testis is manipulated into the scrotum.

To diagnose an ascending testis, several criteria must be satisfied:

1.

It must be recorded by a reliable and experienced observer that the testis once reached the scrotum.

2.

The same observer or one equally experienced must later be unable to manipulate it into the scrotum, and it must remain above the scrotum when the child squats or sits bolt upright with the thighs abducted.

3.

There must have been no surgery or inflammatory episode to have caused the ascent. It is well accepted that a hernia operation can cause iatrogenic testicular ascent.

4.

The testis must remain above the scrotum when the child is anesthetized.

Management

Retractile testes can ascend; therefore, they require follow-up until resolution or a definite diagnosis of ascending testis is made.

Primary ascending testis: once the diagnosis is confirmed, early orchidopexy is advised due to the secondary testicular changes, equivalent to that caused by congenital undescended testis, that would develop [7].

Secondary ascending testis: descent of the secondary ascending testis does not occur with time; therefore, the early repair is indicated to prevent a secondary thermal effect.

Nevertheless, Hack et al. controverted this line of management and argued that ascending testes should be followed up without surgery until puberty because spontaneous descended testes were observed in 84 % of his cases and the testicular volume of the ascending testes became appropriate to the age [8].

5.2.2 Ectopic Testis

Nomenclature

Testicular ectopia and parorchidium

Historical Background

The first case of ectopic testis was reported for the first time by John Hanter in 1786, but the first comprehensive description of the surgical anatomy of testicular maldescent was that of Sir Denis Browne (1938); he classified the retained testis into the truly undescended or incompletely descended organ which halts somewhere along its normal route of descent and the ectopic or maldescended testis which, having traversed the inguinal canal, is diverted from its course to an abnormal position [9].

Incidence

It is a rare congenital anomaly with incidence ranging from 1 to 5 % of all cases of undescended testis [10]. Testicular ectopia specifically describes inguinoscrotal descent outside the normal boundaries; there are five major sites of ectopic testes:

The superficial inguinal pouch

Femoral

Suprapubic

Perineal

Transverse (contralateral hemiscrotum), transverse testicular ectopia, which will be discussed separately

Ectopic testicle was also reported at other abnormal rare positions like the undersurface or the dorsum of the penis, the anterior abdominal wall below the umbilicus, and near the kidney or at the suprarenal glands [10].

One case of intrascrotal supernumerary testicle along with hypospadias was reported by Zur Kenntnis [11].

Perineal ectopic testis is a rare congenital anomaly in which the testis is abnormally situated between the penoscrotal raphe and the genitofemoral fold; it represents approximately 1 % of all undescended testicles [12] (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3

Perineal ectopic testicle in a neonate

Theories based on embryological development attempt to explain the occurrence of ectopic testes. During intraembryonic life, an intra-abdominal gubernaculum develops and terminates in the inguinal region. It guides the testis in transabdominal descent to this area. Later, an extra-abdominal gubernaculum part forms and grows from the inguinal region to the scrotal fundus, guiding the inguinoscrotal descent. Ectopic testes may arise out of failure of proper positioning of the extra-abdominal gubernaculums or its failure to form. If the testis deviates from its course through obstruction (obstructive theory), an ectopic also arises [13, 18].

Testicular ectopia is usually unilateral, but few cases of bilateral ectopia were reported [13] (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.4

Bilateral perineal ectopic testicles

Most authorities agree that testicular cancer is more common in a misplaced testis than in a normally descended organ. Currently, however, there are no satisfactory reports on whether the risk of testicular cancer in ectopic testis is higher than that of cryptorchidism.

Diagnosis is easily based on physical examination that reveals an empty, hypoplastic scrotum and a small mass lateral to it (Fig. 5.5).

Fig. 5.5

Palpation of an ectopic testicle lateral to the scrotum

Ultrasound is diagnostic in almost all cases; even antenatal study reported to pick up few cases; sometimes MRI is indicated, and laparoscopy proved to be useful to diagnose rare cases of ectopy in babies with impalpable testicle [14].

Perineal ectopic testis is frequently associated with an inguinal hernia and can sometimes be associated with other disorders such as hypospadias and scrotal anomalies. A case of bilateral perineal ectopic testis was reported.

Echography can also study traumatic lesions and testicular vascularization. Perineal testis can be discovered, while a complication like torsion or hernia strangulation is the same as undescended testis [15].

Treatment is surgical and there is no indication for hormonal therapy; most authorities agree that testicular cancer is more common in a misplaced testis than in a normally descended organ. Currently, however, there are no satisfactory reports on whether the risk of testicular cancer in ectopic testis is higher than that of cryptorchidism.

Thus, education about testicular self-examination and long-term follow-up of these patients are just as important as operative procedures, and it’s indicated as soon as the diagnosis is affected. There is no need to delay surgery in perineal ectopic testis and there is no need to wait for probable descent. Surgery is indicated even if there is no hernia present because of nonnegligible traumatisms and complications. The testis is relocated and fixed into the scrotal dartos pouch through an inguinal incision. Orchidopexy is usually easy to perform so the length of the testicular vessels and vas deferens is adequate [16].

The gubernaculum was usually found to lie fixed to the perineum, and the ectopic testis and empty scrotum are often well developed. Perineal incision is not necessary and retroperitoneal dissection is not required while perineal adherences are frequent. The long-term prognosis seems to be excellent for some authors; because of the histopathological features involved, prognosis is better than that of cryptorchidism. In fact the natural history of the ectopic testis has been described as normal or less abnormal than that of a truly cryptorchid testis. While Hutcheson, in a comparative study, has found similar pathological findings in ectopic and undescended testis and suggests that ectopic and undescended testis are variant of the same congenital anomaly. What’s sure is that an early detection of the ectopy and its surgical repair on time favored the functionality of the testis [17].

5.2.3 Crossed Testicular Ectopia

Nomenclature

Crossed testicular ectopia (CTE), transverse testicular ectopia, testicular pseudoduplication, unilateral double testis, and transverse aberrant testicular maldescent

Historical Background

It is an uncommon anatomical abnormality in which both the gonads migrate toward the same hemiscrotum; only about a hundred cases have been reported in literature. The ectopic testis may lie in the opposite hemiscrotum, in the inguinal canal, or at the deep inguinal ring. An inguinal hernia is invariably present on the side to which the ectopic testis is migrated.

Variations in the anatomical position of the vasa deferentia and abnormalities of insertion of the vas into the testis can occur. Fusion of vasa deferentia has been described previously also based on the presence of various associated anomalies,

The largest incidence is found in Europe and Japan.

The most frequent anomalies associated with CTE are inguinal hernia, persistent Müllerian remnants, and incomplete descent of the nonectopic testis.

Persistent Müllerian duct remnants—tubes, rudimentary uterus, and hemiuterus—occurred in 38 % of TTE cases.

TTE has been classified into three types:

1.

Associated with inguinal hernia alone (40–50 %)

2.

Associated with persistent or rudimentary Müllerian duct structures (30 %) (Fig. 5.6)

Fig. 5.6

Crossed testicular ectopia

3.

Associated with other anomalies without Müllerian remnants (inguinal hernia, hypospadias, pseudohermaphroditism, and scrotal abnormalities) (20 %) [21]

The mean age at presentation is 4 years. In most of the cases, the correct diagnosis was not made preoperatively and the condition was revealed during herniotomy. Recently, MRI and MR venography have been suggested for preoperative location of impalpable testis. Laparoscopy is useful for both diagnosis and management of TTE and the associated anomalies [22, 23]. Treatment includes transscrotal orchidopexy or extraperitoneal transposition of the testis, search for Müllerian remnants and other anomalies, and long-term postoperative follow-up. Like all dysgenetic testes, infertility and progression to malignancy are relatively frequent with TTE [24].

Associated Müllerian duct structures, if any, should be ruled out by laparoscopy or minilaparotomy in the same sitting.

Persistent Müllerian duct remnants—rudimentary uterus and hemiuterus—occurred in 38 % of CTE cases. Persistence of Müllerian remnant in phenotypically normal males represents a recessive trait with male sex restriction, in chromosome 19, resulting in abnormal Müllerian-inhibiting substance (MIS) receptors, or inactive forms of MIS or even inadequate synthesis of MIS, by the fetal testis (Fig. 5.7).

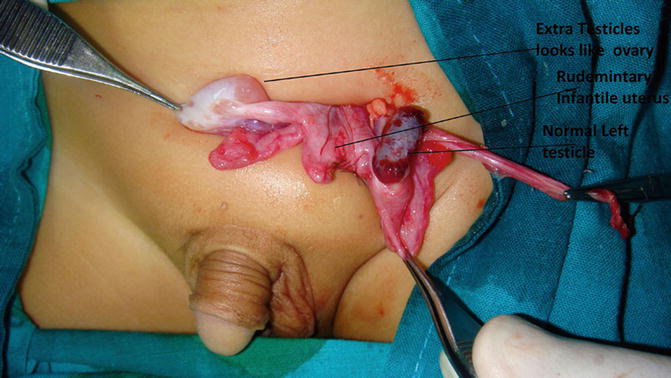

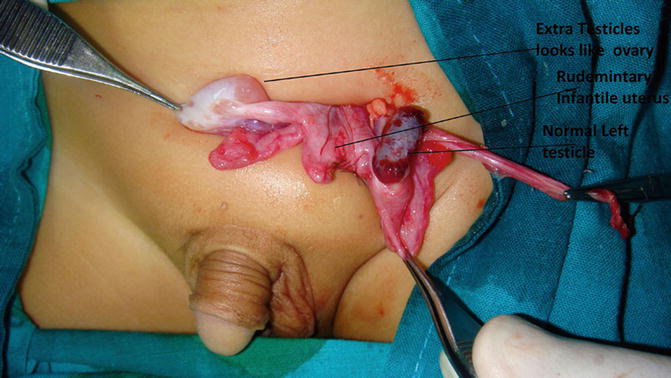

Fig. 5.7

A child had CTE with an extra testicle that looks like an ovary and a primitive uterine structure “Müllerian ruminant” in between

Crossed testicular ectopia is a rare congenital anomaly in which both testes are located in one hemiscrotum as a result of deviation from normal testicular descent. In most cases the right testis is found in the left hemiscrotum. The ectopic testis has its own spermatic cord (vas and blood vessels), which originates from the appropriate abdominal site but descends to the opposite side after passing anterior to the urinary bladder [27].

5.2.4 Anorchia and Monorchia

Nomenclature

Embryonic testicular regression, vanishing testis syndrome, and monorchia; an individual having monorchism can be referred to as monorchid.

Definition

Anorchia is defined as the absence of testes in a 46, XY individual with a male phenotype; monorchia is a term applied for unilateral cases.

Incidence

It affects one in 20,000 male births and occurs in 1/177 cases of cryptorchidism. Bilateral anorchia is a very rare condition; familial cases are occasionally reported [25].

Monorchism is a normal phenomenon in nonhuman animals, notably in beetles.

Although some patients with anorchia present with ambiguous external genitalia or microphallus, most have a normal phenotype.

But many cases are associated with other urinary or anorectal and limb anomalies Fig. 5.8.

Pathophysiology

As the differentiation of the male genital tract and external genitalia is dependent on anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and testosterone, this suggests that functional testes were present, but disappeared in utero in these cases. The familial occurrence of anorchia and its association with other anomalies suggest a genetic origin, but the genetic cause remains unknown. However, exploratory laparoscopy has suggested that at least some cases of anorchia are the result of prenatal testicular vascular accident associated with torsion during testicle descent.

Fig. 5.8

Bilateral anorchia with an empty scrotum

The basal plasma concentrations of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibin B, and testosterone were very low or undetectable with high level of FSH hormone and, together with 46, XY complement, are sufficient for diagnosis of anorchia, and the hCG test is not necessary [26].

There are three theories to explain congenital absence of the testis: (a) absence of testicular development during fetal period, (b) discontinuation of vascular supply to the testes during fetal period, and (c) atrophy caused by intrauterine testicular torsion [27].

Discontinuation of testicular vascularization during fetal period would occur by extravaginal torsion (spermatic cord torsion) that would be the most frequent mechanism involved in testicular agenesis.

Absent testicles (acquired anorchia) could be due to testicular regression syndrome where dystrophic calcification and hemosiderin deposits are found at the site of the testis, with no evidence of viable testicular tissue, but with relatively normal spermatic cord elements.

The genitalia of these patients varied from a female appearance, ambiguous external genitalia, to normal male aspect and anorchia.

Diagnosis

Some 10–20 % of undescended testes are impalpable; it is necessary to establish whether the testis is absent (anorchia), is intra-abdominal, or is represented by an atrophic nubbin of tissue within the inguinal canal. In approximately 40 % of cases of “impalpable testis,” the gonad lies intra-abdominally; in 30 % it has “vanished,” with the vas and vessels ending blindly deep to the internal inguinal ring; in 20 % the vas and vessels end blindly within the inguinal canal; and in 10 % the testis is normal but concealed within the inguinal canal [26].

Anti-Müllerian hormone is used to facilitate the evaluation of intersex disorders and as a marker of ovarian reserve assessment in the infertility cases. When the testes are non-palpable, a single measurement of serum AMH level can distinguish between cryptorchidism and anorchia.

Diagnostically, the lack of testosterone response to hCG stimulation is the hormonal hallmark of bilateral congenital anorchia.

Ultrasound is unreliable in distinguishing between anorchia and intra-abdominal testis, giving both false-positive and false-negative findings, but it is sometimes helpful in visualizing a testis within the inguinal canal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also unhelpful alone, although more reliable when combined with angiography, but this requires a general anesthesia.

Consequently, laparoscopy remains the investigation of first choice in cases of impalpable testis, being both highly reliable and providing positive guidance for further management. In this regard, there are five possible laparoscopic findings.

Excision of any testicular and vas remnants is recommended in cases of anorchia, and implantation of testicular processus at the adult age could be considered especially in bilateral cases, but the indication in unilateral case (monorchia) is controversial.

5.2.5 Microorchidism

It is a genetic disorder found in males, characterized by abnormally small testes. The condition is associated with (and often secondary to) a number of other genetic disorders, including Klinefelter’s syndrome and Prader–Willi syndrome, as well as other multiple malformation disorders. The degree of abnormality of the testes can be determined by the use of an orchidometer. In addition, microorchidism may also occur as a result of shrinkage or atrophy of the testis due to infections like mumps and post trauma, in survivors from testicular torsion, and many cases after orchidopexy may have a small testicle.

5.3 Supernumerary Testicles

Nomenclature

Polyorchia, triorchidism, supernumerary testicles

Historical Background

Definition

Polyorchidism is an uncommon congenital anomaly defined as the presence of more than two histologically proven testes. In this type of unusual abnormality of the genital tract, most patients with supernumerary testicles are asymptomatic and have painless groin or scrotal masses; triorchidism is the most common variety of polyorchidism, and the supernumerary testis is frequently reported on the left side.

Associated Anomalies

The most common associated anomalies (about 80 %) are maldescent of the testis or cryptorchidism and indirect hernia. The rest are associated with torsion, infertility, malignancy, hydrocele, epididymitis, or varicocele; in about 7 % of supernumerary testes, malignant degeneration and/or transformation occurs [31] (Fig. 5.9).

Fig. 5.9

Operative finding showing two functional testicles in the right side

It is worth to mention that most reported cases don’t have any scrotal anomalies and cases of accessory scrotum almost do not contain any extra testicle (Chap. 4.5); normal spermatogenesis is usually absent in the majority of supernumerary testis

Holder [32] described a patient with five testes, two in each scrotal sac and one in a small scrotal pouch in the perineum. One case of intrascrotal supernumerary testicle along with hypospadias was reported by Zur Kenntnis [33].

Etiology

The exact explanation for the production of polyorchidism is not known, although several theories have been proposed, including anomalous appropriation of cells, initial longitudinal duplication of the genital ridge, and transverse division of the genital ridge, either through some local accident of development of peritoneal bands.

Classifications

A recent functional classification based upon the embryogenic development is provided [34]:

Polyorchidism occurs in two primary forms: type A and type B.

Type A: the supernumerary testicle is connected to a vas deferens. These testicles are usually reproductively functional. Type A is further subdivided into:

Type A1: complete duplication of the testicle, epididymis, and vas deferens.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree