(1)

Al Agouza, Cairo, PO, Egypt

The gynecologic examination of the female genitalia of children and young adults belongs in the hands of specialists and should be performed in the appropriate environment. The most important task of such an examination is the distinction between true developmental anomalies and anatomical findings mimicking such anomalies. Even newborn females can be successfully examined without any large effort expenditure. In most cases, the external inspection of the vestibule is enough to reach a diagnosis. In other case scenarios, vaginoscopy and gynecologic speculum examination may be necessary. Additional imaging studies include abdominal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging.

Most of the female genital tract malformations affect the uterus, and therefore, they are often referred to as uterine or Müllerian (paramesonephric) malformations. However, many of the anomalies that affect the Müllerian ducts could originate as a mesonephric (Wolffian) anomaly or in the female gubernaculum. Female genital tract malformations are frequent but are not always detected. Therefore, their true prevalence in the general population is unknown because many are asymptomatic and not noticed [1].

Congenital anomalies of the female genital tract result from Müllerian duct anomalies and/or abnormalities of the urogenital sinus or cloaca. Failure of fusion of the Müllerian ducts results in a wide variety of fusion abnormalities of the uterus, cervix, and vagina. Müllerian duct abnormalities may occur alone or in association with urogenital sinus or cloacal malformations. Persistence of the cloaca is believed to be caused by an abnormal development of the dorsal part of the cloaca and the urorectal septum. Urogenital sinus malformations occur after the cloaca has been organized into the urogenital sinus and the anus. Early and complete assessment of the patients, including radiological and biochemical examinations, is mandatory to provide an optimal basis for treatment that will have a great influence on the quality of the patient’s later life. Due to the close embryological relationship between the urinary and the genital tract, malformations involving both organ systems are very common.

Normal variations of a child’s hymenal membrane, fusion of the labia minora, hymenal polyps, and hypertrophy of the preputium of the clitoris are the entities most likely to be mistaken for real developmental malformations. The most important asymptomatic developmental anomaly of the vagina and the uterus is the Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome (uterine and vaginal agenesis). Developmental malformations, such as hymenal atresia, vaginal septum formation, and Müllerian anomalies in general, tend to be symptomatic, presenting with hematometra, hematocolpos, or dysmenorrhea. The treatment of genital developmental anomalies is generally not difficult but requires the appropriate clinical and surgical expertise. The development of the normal female reproductive tract is a complex process. The indifferent gonad differentiates to the ovary. The mesonephric, Wolffian, and Müllerian ducts differentiate in an orchestrated manner to form the uterus, vagina, and lower urinary tract. The fused Müllerian ducts form the uterus up to the external cervical os, and the inducing mesonephric ducts regress cranially, though they enlarge caudally from the level of the cervical os, form the sinuvaginal bulbs, incorporate the Müllerian tubercle’s cells, and give rise to the vaginal plate (the cavitation of which is covered by Müllerian cells).

Etiopathogenesis of the Malformations of the Genital Tract Female

The direct cause of genital malformations is unknown despite the many different theories and hypotheses in this area. The familiar incidence is difficult to research though it is clear that it does exist. The karyotype is generally normal, but sometimes there are mosaicisms or other anomalies that do not seem related to the malformation. Duncan et al. [1] speculated that the combination of Müllerian duct, renal, and skeletal anomalies seen in some anomalies is due to a teratogenic event late in the fourth week of fetal life, when the cervicothoracic somite mesoderm and pronephric duct are in close proximity. However, the embryological development of the genital tract and the chain of anatomical events leading to the production of the malformation are better known. Disordered differentiation can result in congenital abnormalities affecting the female reproductive tracts, renal tract, and lower intestines. A number of rudimentary structures can persist and be encountered in clinical practice, most commonly these are derived from the Wolffian ducts.

The most frequent classifications of the female genital tract have been those based on the Müllerian development, and therefore we should speak about the following:

1.

Anomalies by total or partial agenesis in one or both Müllerian ducts: unicornuate uterus and Rokitansky syndrome

2.

Anomalies by total or partial absence of fusion: didelphic uterus and bicornuate (bicollis and unicollis) uterus

3.

Anomalies by total or partial absence of reabsorption of the septum between both Müllerian ducts: septate and subseptate uterus

4.

Anomalies by lack of posterior development: hypoplastic uterus

5.

Segmentary defects and combination of the different anomalies

8.1 Clitoris

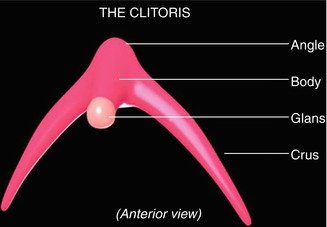

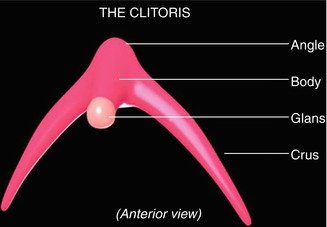

The clitoris is a highly neurovascular erectile part of the external genitalia; embryologically, it is derived from undifferentiated phallus; the major difference between female external genitalia and male genitalia is that female genitalia are separate from the urethra, and it consists of the paired corpora, vestibular bulbs, and the glans. The corpus clitoris has two corpora cavernosa with erectile tissue surrounded by dense fibrous tissue around each corpus. These corpora are separated incompletely from each other with a medial located by a fibrous pectiniform septum, and each crus clitoridis is attached to the corresponding ischial ramus [2].

The clitoris plays a major role in female sexual function and is very closely related to the distal urethra and vagina. The clitoris is suspended by the superficial and deep suspensory ligaments. The superficial suspensory ligament is attached to the deep fascia of the mons and glans and body of the clitoris further extending into the labia majora. The deep suspensory ligament originates from the symphysis pubis and attaches to the body, bulbs, and glans of the clitoris. These may provide clitoral stability during sexual intercourse. Accurate knowledge of the clitoris, its relations, and neurovascular supply is crucial in performing clitoral reduction for clitoromegaly to achieve normal morphology without affecting sexual function. It is important to preserve the bulbs with the erectile tissue related closely to the ventral aspect of the clitoris for sexual function and suspensory ligaments to maintain the anatomical position of the clitoris during surgery.

Details of the female genitalia gross anatomy and histology are described in various reports in the literature. Schober and colleagues evaluated internal portions of the clitoris using cadaveric materials [3]. Also magnetic resonance imaging and cadaveric studies have helped better understand the detailed structure of the clitoris. The corpora cavernosa of women have been shown by MRI using a fat saturation technique. Using that technique, it was revealed that all the clitoral structures, from the crus to the glans clitoridis, were colored bright white; thus, it can be said that the whole clitoris is erectile. It was also revealed that the clitoris is highly vascular, even under conditions of nonarousal. This fact is important because studies have shown that some of the functions like erotic stimulation of the clitoris are useful for female characteristics [4].

In order to verify whether ethnicity has an effect on the size of external genitalia in newborns, 570 full-term infants, Jews (221) and Bedouins (349), at the neonatal department of the Soroka Medical Center were examined. Clitoral length, the distance between the center of the anus to the fourchette (AF), and the distance between the center of the anus and the base of the clitoris (AC) were measured, and the AF/AC ratio was calculated for the females. Significant differences in clitoral length (12.6 %) between the Jewish group (5.87 ± 1.48 mm) and the Bedouin group (6.61 ± 1.72 mm) (p < 0.01) and in the ratio of AF to AC between the two ethnic groups (p < 0.01) were found. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report ethnic differences in genital sizes of newborns [5] (Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.1

Anatomical parts of the clitoris

8.2 Clitoral Anomalies

1.

Congenital clitoromegaly

2.

Clitoral agenesis

3.

Clitoral duplication

4.

Bifid clitoris

5.

Clitoral cyst

6.

Accessory phallic urethra

7.

Clitoral hood anomalies

8.2.1 Clitoromegaly

Clitoral hypertrophy

Pseudoclitoromegaly

Clitoromegaly of premature baby

Nomenclature

Macroclitoris

Definition

Clitoromegaly is defined as a measure of the clitoral index (width × length in mm) more than 15 mm2 in the newborn. The ±2 SD values for clitoral length were 4.93 ± 1.61 mm, and the 97th percentile was 8.04 mm; therefore, the neonate with a clitoris length of over 8 mm must be monitored, and those over 10 mm are accepted as pathological [6].

Historical Background

It is believed that the discovery of the clitoris is by the Renaissance anatomists in 1559 and Realdo Colombo in 1561, but Gabriele Falloppio (who discovered the fallopian tube) also claimed that he was the first to discover the clitoris in 1561. Sinistrari, a Roman inquisitor of the early sixteenth century, was the first one to report about women with elongated clitorises [7].

Etiology

Clitoromegaly can be either congenital or acquired. The congenital forms are caused by hormonal disturbances or intersex states; usually they are obvious at birth, but when the clitoromegaly develops later on in life, the underlying etiology should be explored and acquired causes should also be considered, which could be either hormonal or nonhormonal. In the hormonal causes, an androgen excess is the main contributing factor of the clitoral enlargement. The most important endocrinopathies are non-polycystic ovarian hypertestosteronism, including Leydig cell tumors, granulosa cell tumors, thecomas, sex-cord stromal tumors, and mixed germ cell tumor of the ovary, and Swyer syndrome, which can present with markedly elevated testosterone levels near normal male range, are fast growing, and correlate with rapid development of symptoms often over the course of a few months, and polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Swyer syndrome is associated with absent testicular differentiation in a 46,XY phenotypic female, where a hypoplastic uterus and clitoris enlargement are obvious and the association of clitoral hypertrophy without hirsutism, female internal genitalia, and a 46,XY karyotype. Clitoral enlargement can be explained by transient androgen secretion by the hilar cells found in the resected gonads.

Silver–Russell syndrome (SRS) is a rare condition (1/3,000–1/100,000 newborns), and the female infant with SRS will have cardiac malposition and asymmetrical enlargement of the clitoris [8].

In females with Fraser syndrome, clitoromegaly was the most common genital abnormality (36.8 %). However, prenatal androgen exposure because of adrenal dysfunction or a related enzyme defect is the main reason for clitoromegaly. For isolated clitoral hypertrophy, female pseudohermaphroditism differs from external genitalia masculinization due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Masculinization of the external genitalia to varying degrees occurs if hyperandrogenism is seen before 12 weeks of gestation, although after the 12th week it only results in a single, isolated clitoromegaly [9].

Occasionally, adrenal tumors such as adrenocortical carcinomas or adenomas can also lead to clitoromegaly. More commonly, however, patients presenting with ambiguous genitalia are found to have late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or CAH, including deficiencies in 21-hydroxylase, 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 11-β-hydroxylase, and 17-α-hydroxylase. In contrast to classical CAH where virilized genitals are present at birth, fetal exposure to danazol has been described as a cause for clitoromegaly (Figs. 8.2 and 8.3).

Figs. 8.2 and 8.3

Clitoromegaly with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

Although hemangioma is a common neoplasm, clitoromegaly secondary to cavernous hemangioma is extremely rare, and only few cases have previously been reported in the English literature [8]. Epithelioid hemangiomas, also known as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, which are benign vascular tumors that usually arise in the skin are reported to arise from the clitoris. Other primary clitoral tumor types reported are transitional cell, melanoma, neurofibromatosis of the external genitalia, and lymphoma. Epidermoid cyst is rare, and it can be the consequence of trauma. This observation underlines the importance to evoke a cystic origin for clitoral hypertrophy and encourages to propose imaging (ultrasound, MRI) in case of etiologic doubt [10].

The association between a cloacal anomaly and clitoromegaly is well known and has been previously reported in many articles. Clitoral hypertrophy is seen also in genitopatellar syndrome which is an autosomal dominant inheritance disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree