(1)

Al Agouza, Cairo, PO, Egypt

13.1 Embryological Background

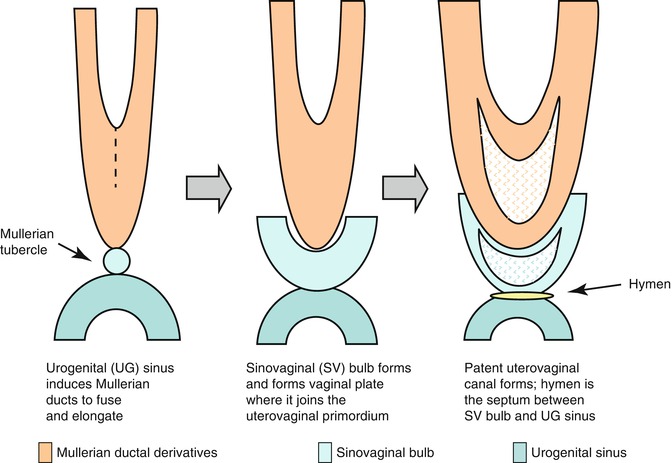

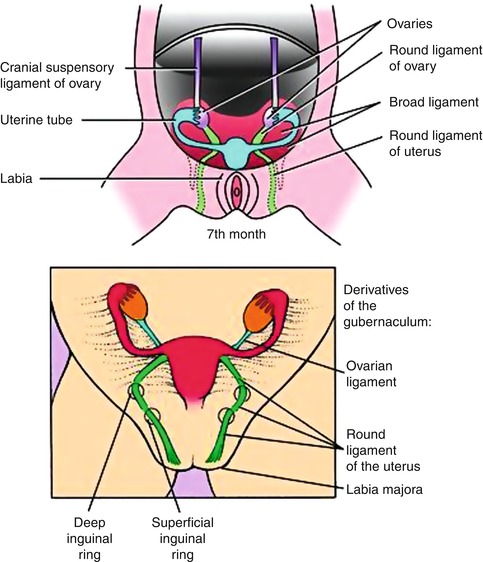

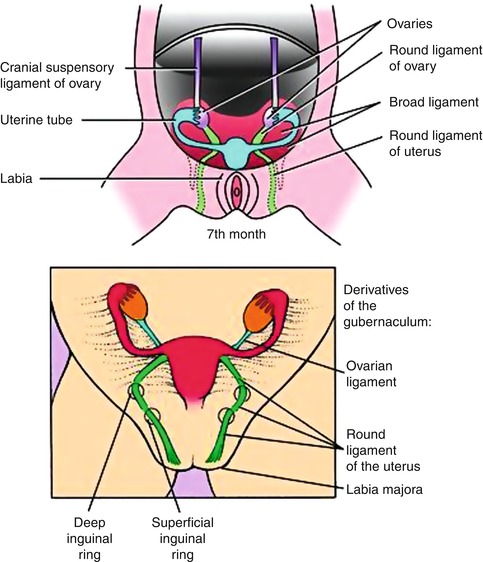

In the female fetus, the Müllerian ducts normally meet in the midline by 8 weeks and subsequently give rise to the uterus, cervix, and approximately three-fourths of the vagina. The caudal ends fuse in the midline and are occluded by the Müllerian tubercle that forms the hymen. The distal vagina is formed by the urogenital sinus. Duplication of the female reproductive tract is the result of failure of the paired Müllerian ducts to fuse; the extent of duplication reflects the extent of this failure. Various congenital anomalies of the female tract such as agenesis, failure of vertical or lateral fusion, and failure of canalization occur when normal development of Müllerian duct disrupts in any stage of the developmental milestones (Fig. 13.1).

Fig. 13.1

Diagram showing the embryonic steps for formation of the female genital system

Fusion anomalies of the uterus are of medical importance for three reasons. First, they have been implicated in serious complications of the sexual functioning, pregnancy, and labor of the female. Second, a constellation of deformities has been noted recently in infants born to mothers who have duplication of the Müllerian ducts. These malformations, usually limb reduction anomalies, are attributed to embryonic compression resulting in a vascular insult with necrosis and loss of normal tissues. Third, although duplication of the human reproductive system seems in the majority of cases to be a sporadic and isolated anomaly, there are several reports of its occurrence in more than one family member. In addition, it is a characteristic of various uncommon syndromes, and, more importantly, it is frequently associated with other genitourinary malformations [1].

Simply the embryology of the uterus and cervix passes through three stages [2]:

First stage

Short.

Begins at the 10th week.

Medial aspects of the Müllerian ducts fuse, starting at the middle and proceeds at both directions of the median septum.

Second stage

10th–13th week.

Rapid cell proliferation and filling of triangular space between 2 uterine cornua.

Forms thick upper median septum, wedge-like, and gives rise to the external contour of the fundus.

Lower portion of the median septum is resorbed, unifying the cervical canal and upper vagina.

In this stage, the following processes come about in sequence:

Elongation

Müllerian ducts elongate as far caudad as the urogenital sinus.

Fusion

These ducts fuse, from caudad to cephalad.

Occurs up to the level of what will become the uterine fundus.

The most cephalad parts of the Müllerian ducts remain unfused and become the fallopian tubes.

Fused portions of the Müllerian ducts lie side by side, each composed of solid tissue.

Internal Canalization

Occurs about the 10th week.

Central canal is formed in each of the solid ducts.

When completed, 2 channels lie side by side, separated by a septum.

Septal Resorption

Occurs caudad to cephalad at about the 20th week

Third stage

13th–20th week.

Degeneration of the upper uterine septum occurs, starts at the isthmic region and proceeds cranially up to the top of the fundus.

Unified uterine cavity is formed.

Vagina

Develops from a combination of the Müllerian tubercles and urogenital sinus

Sinovaginal bulbs

Solid aggregates that form from proliferation of cells from the upper portion of the urogenital sinus.

Develop into cord and vaginal plate.

Plate canalizes and proceeds cranially to the developing cervix.

Completed at about the 21st week of intrauterine life.

13.2 Müllerian Duct Anomalies (MDA)

(a)

Müllerian duct agenesis

(b)

Duplication of the Müllerian ducts

(c)

Müllerian duct fusion anomalies

Historical Background

Müllerian ducts are named after Johannes Peter Müller, a German physiologist who described these ducts in his text “Bildungsgeschichte der Genitalien” in 1830. The earliest report of concomitant anomalies of the genital and urinary systems appeared in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Incidence

MD malformations are not so rare, but are not always detected. Therefore, their true prevalence in the general population is unknown because many are asymptomatic and not noticed. In a recent systematic review, the mean prevalence of Müllerian congenital malformations in the general population was up to 7 % (ranging from 0.4 to 10 %) [3].

Clinical

Many females with genital tract malformations are asymptomatic, but others suffer from a wide range of symptoms and problems that may present at any age and at any time.

In general, symptoms depend on the type of anomaly and the reproductive age; the following are the most frequently observed symptoms:

Obstetric complications due to a lack of fusion

Amenorrhea in Müllerian agenesis

Intra- and postmenstrual dysmenorrhea in obstructive anomalies

Postmenstrual bleeding in the communicating uteri

Pelvic tumors that are caused by the retention of menstrual debris and secretions

Extra gynecologic problems (urinary, skeletal, or auditory) [4]

Early identification of MDAs helps avoid prolonged symptomatic periods in young adolescents and the complications that may subsequently arise, such as hydronephrosis (mostly in obstructed anomalies), endometriosis, and infertility. Despite the importance of early diagnosis of MDA in children and adolescents, most of the imaging reviews currently available in the literature focus on the diagnosis of MDA in adults only.

Renal tract anomalies are associated with MDA in up to 30 % of cases because of the close embryological relationship between the paramesonephric and mesonephric ducts. Therefore, it is imperative that the renal tract be investigated in all patients who present with MDA. The most common renal tract anomaly associated with MDA is renal agenesis; however, duplicated collecting systems, renal duplication, horseshoe kidney, crossed renal ectopia, and cystic renal dysplasia have also been reported.

Classifications and Nomenclature

Various types of uterine anomalies and their classification are reported; MDAs have been classified by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine according to anatomical findings [5] (Table 13.1).

Table 13.1

American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of MDA

Class | Percentage of MDAs | Description |

|---|---|---|

I | 5–10 | Müllerian agenesis or hypoplasia |

I-A | Vaginal agenesis or hypoplasia (uterus may be normal or may exhibit one or more of a variety of malformations) | |

I-B | Cervical agenesis or hypoplasia | |

I-C | Fundal agenesis or hypoplasia | |

I-D | Fallopian tube agenesis or hypoplasia | |

I-E | Combined agenesis or hypoplasia (two or more findings from classes I-A through I-D) | |

II | 10–20 | Unicornuate uterus |

II-A | Rudimentary horn with an endometrial cavity that communicates with single-horned uterus | |

II-B | Rudimentary horn with an endometrial cavity that does not communicate with the uterus | |

II-C | Rudimentary horn with no endometrial cavity | |

II-D | No rudimentary horn | |

III | 5–20 | Uterus didelphys |

IV | 10 | Bicornuate uterus |

IV-A | Complete bicornuate uterus (septum extends to the internal or external os) | |

IV-B | Partial bicornuate uterus (septum is confined to the fundal region) | |

V | 55 | Septate uterus |

V-A | Complete septate uterus (septum extends to the internal os) | |

V-B | Partial septate uterus (septum does not reach the internal os) | |

VI | Arcuate uterus | |

VII | 69 | DES-related uterine anomalies |

VII-A | T-shaped uterus | |

VII-B | T-shaped uterus with dilated horns | |

VII-C | Uterine hypoplasia |

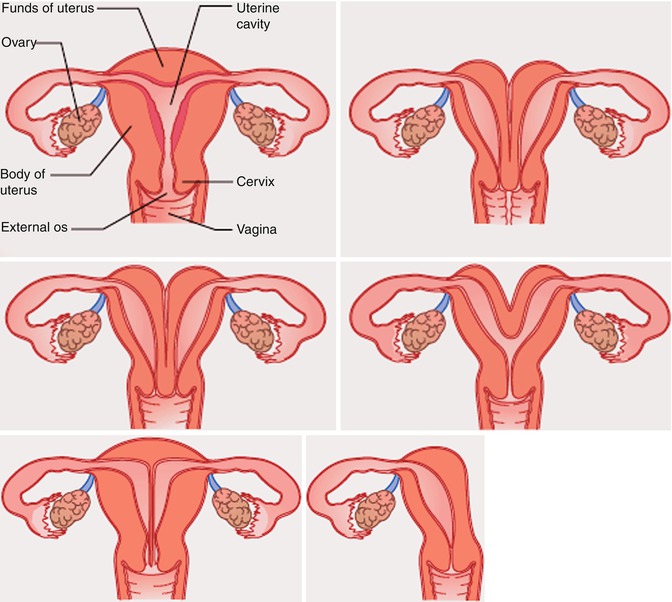

However, other authors have suggested alternative simple classification systems for these anomalies [4] (Figs. 13.2 and 13.3).

Class I: Müllerian agenesis or hypoplasia

Class II: unicornuate uterus

Class III: uterus didelphys

Class IV: bicornuate uterus

Class V: septate uterus

Class VI: arcuate uterus

Investigations

MRI is the undisputable standard modality for imaging uterine anomalies. Its excellent soft tissue contrast helps in the detection and characterization of lesions in the uterine cavity or the myometrium; it has high accuracy and detailed delineation of the uterovaginal anatomy, is noninvasive, and lacks ionizing radiation. This is especially true for pediatric patients, in whom the use of vaginal US probes is not recommended [6].

Management

Naturally, therapeutic approaches are equally variable due to the diversity of anomalies, clinical presentations, and combinations. Moreover, when needed, therapy will always be surgical and will frequently be simple procedures, but therapy is not necessary in the majority of malformations. Certainly, the most controversial aspect of genital malformations is that their correct diagnostic evaluation and classification should be based on etiopathogenic knowledge of the anomaly and the suspicion of other associated anomalies that may exist, so suggesting the appropriate therapeutic strategy [7].

13.2.1 Müllerian Duct Agenesis (Müllerian Aplasia)

Müllerian aplasia is the absence of the uterus, cervix, and upper vagina. It represents the most severe type of MDA, consisting of segmental agenesis and variable degrees of uterovaginal hypoplasia. The lower third of the vagina is typically present secondary to normal formation of the sinus vagina and the external genitalia are normal. Most often the diagnosis of Müllerian aplasia is labeled as Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. In 10 % of cases, a rudimentary Müllerian structure, as a rudimentary uterus, is identified. This structure can be either functional (endometrial layer present) or nonfunctional (endometrial layer absent) (Fig. 13.4).

Fig. 13.4

A diagram of the Müllerian agenesis

Associated Anomalies

Altogether, associated upper urinary tract malformations are found in about 40 % of cases. Mainly, they include unilateral renal agenesis (23–28 %), ectopia of one or both kidneys (17 %), renal hypoplasia (4 %), horseshoe kidney, and hydronephrosis. Skeletal and in particular, vertebral (Klippel–Feil anomaly; fused vertebrae, mainly cervical; scoliosis). Hearing defects and, more rarely, cardiac and digital anomalies (syndactyly, polydactyly) [8].

The presence of other associated anomalies suggests that an initial insult to the intermediate mesoderm leads to alteration of the cervicothoracic somites and the pronephric ducts. Most cases are sporadic; however, several reports of familial clustering are suggestive of a genetic cause. These cases of familial clustering appear to occur by autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity.

Incidence

The estimated prevalence is 1 in 5,000 females with XX chromosomes. It is the third most common cause of primary amenorrhea after pregnancy and gonadal failure (such as from Turner syndrome). Queen Amalia of Greece was found postmortem to have had this syndrome. Her inability to provide an heir contributed to the overthrow of her husband, King Otto [9].

13.2.2 Classification

Typical MRKH: isolated uterovaginal aplasia/hypoplasia (64 % of the cases)

Atypical MRKH: uterovaginal aplasia/hypoplasia with renal malformation or uterovaginal aplasia/hypoplasia with ovarian dysfunction (24 %)

MURCS syndrome: uterovaginal aplasia/hypoplasia with renal malformation, skeletal malformation, and cardiac malformation (12 %) [10]

Management

The management of Müllerian aplasia consists of correction of the anatomical abnormality, along with counseling for the patient and her parents; some patients opt to have a vagina created, and this was discussed with vaginal anomalies. In the presence of a functional Müllerian remnant, regardless of whether it is “communicating,” medical suppression of menses can be initiated and should be followed by laparoscopic removal of the hypoplastic remnant. Surgical management is mandated because of the potential for pregnancy in the rudimentary horn with possible catastrophic consequences.

13.2.3 Incomplete Müllerian Fusion

Incidence

The incidence of incomplete Müllerian fusion is difficult to estimate, as many patients are asymptomatic; however, the incidence is quoted as between 0.1 and 3 %.

Traditionally, incomplete Müllerian fusion results in two hemiuteri each associated with one fallopian tube, but various forms of incomplete Müllerian fusion exist. Incomplete Müllerian fusion represents a range of conditions from a complete hemiuteri to an atretic rudimentary horn. There have been several case reports of familial aggregates of incomplete Müllerian fusion, also several syndromes have been identified with incomplete Müllerian fusion as a common component. Contrary to the cases of vaginal atresia and vaginal septa, there have been several isolated or nonsyndromic cases of incomplete Müllerian fusion identified for study leading investigators to look for candidate genes in these cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree