Chapter 57 URODYNAMIC EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT WITH PROLAPSE

Symptoms caused by pelvic organ prolapse may or may not be specific to the prolapsing compartment or compartments, and the correlation of many pelvic symptoms with the extent of prolapse is weak.1,2 Many women with pelvic organ prolapse have no symptoms, especially if the prolapse remains inside the vagina.3 Others present with symptoms in addition to the vaginal bulge, as a result of the associated organ dysfunction. It is recommended that symptoms be elucidated in four primary areas: lower urinary tract, bowel, sexual symptoms, and other local symptoms.4 Documentation of symptoms not only serves as a guide to treatment but also permits an accurate assessment of post-treatment results.

There is general agreement that the aim of urodynamic testing is to reproduce symptoms of the patient under controlled and measurable conditions. Ideally, this allows diagnosis, helps with informed treatment choice, and improves treatment outcome. Specifically, the testing identifies or excludes contributing factors to incontinence or voiding dysfunction and assesses their relative importance.5 However, the role of urodynamics in the evaluation of symptoms related to prolapse is not yet fully established. A recent Cochrane review attempted to test the hypotheses that urodynamic testing improves the clinical outcome of incontinence management, that it alters clinical decision-making, and that one type of test is better than another in these areas.6 Only two trials were found, but the numbers of patients were too small to determine whether clinical outcomes were affected by the urodynamics. This chapter reviews the various tests that are available and may be helpful in patient evaluation.6

LOWER URINARY TRACT SYMPTOMS

Urinary incontinence is one of the most common symptoms associated with prolapse. Blaivas and Groutz7 described the clinical evaluation in detail. However, the specific symptoms and their impact on the patient’s quality of life should be elucidated in each case.

Urinary symptoms may include stress incontinence; symptoms of bladder overactivity, such as frequency, nocturia, urgency, and urgency incontinence; and voiding symptoms such as difficulty with bladder emptying. The mechanisms for stress incontinence include hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency. It is not unusual for patients to present with a combination of urge and stress incontinence.8,9 If both symptoms are present, the patient has mixed incontinence.10 Mixed incontinence is especially common in older women. Often, however, one symptom (urge or stress) is more bothersome to the patient than the other. Identifying the most bothersome symptom is important in targeting diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Many women with severe prolapse recall that, as the prolapse worsened, their stress incontinence symptoms improved. Reducing the vaginal prolapse with a pessary or a speculum during the examination by the clinician can produce stress incontinence in up to 80% of clinically continent patients with severe prolapse.11–14 This phenomenon has been termed latent, masked, occult, or potential stress incontinence, and it should be elicited when considering therapy. Although the clinical experience reported refers primarily to cystocele, occult incontinence may also be unmasked in a similar manner in patients with severe middle or posterior compartment prolapse. The postulated mechanism for continence may be urethral kinking by the cystocele or external compression of the urethra.15

Other storage symptoms, such as frequency, nocturia, and urgency, have been listed as symptoms of prolapse,16 although the mechanism is unknown and there are frequently other associated factors. Urge incontinence may also be present. However, urge incontinence is a common complaint in patients without organ prolapse, may or may not be the result of detrusor overactivity,17 and becomes more prevalent with aging. Patients with advanced organ prolapse and urge incontinence have also been shown to have detrusor overactivity15 that may resolve after surgical correction of the prolapse.13,18 The mechanism is unclear; however, many of those patients may have outflow obstruction caused by the prolapse that is alleviated after repair. Nguyen and Bhatia reported resolution of urgency incontinence after pelvic prolapse repair in patients who had no obstruction preoperatively.18

A number of tools are now available to aid the clinician in elucidating the symptoms and their impact on quality of life, to gain as accurate a picture as possible. These tools include questionnaires, voiding diaries, and pad tests, which are also used to evaluate treatment outcomes.19

Difficult voiding symptoms are common with severe prolapse and should be elicited. Patients with prolapse may have urethral kinking or external pressure on the urethra that not only prevents incontinence but also may cause difficult voiding.15 They occasionally have to digitally reduce the prolapse to void (splinting) or need to assume unusual positions to initiate or complete micturition.4 Urinary splinting has been reported to be 97% specific for severe anterior prolapse.20

Urodynamic abnormalities with decreased uroflow, increased postvoid residual urine,21 and bladder outlet obstruction have been reported.15,22,23 The degree of obstruction may be related to the severity of the prolapse.15 Acute urinary retention secondary to the prolapse is rarely seen.24

INITIAL EVALUATION OF URINARY SYMPTOMS

The initial evaluation includes a history, physical examination, urinalysis, and measurement of postvoid residual urine.25 The basic evaluation may be satisfactory for proceeding with treatment, including surgery, for patients with straightforward stress incontinence associated with hypermobility and normal postvoid residual volume.10 However, the International Scientific Committee of the Third International Consultation on Urinary Incontinence advised that urodynamic testing is highly recommended for women who desire interventional treatment,25 although the specific chapter indicates the lack of evidenced-based medicine for this recommendation.5 Furthermore, Diokno and coworkers26 showed that a systematic history, vaginal speculum examination and postvoid residual measurement were 100% accurate in identifying patients who had pure type II stress incontinence on urodynamic studies. Other groups have shown a positive correlation of symptoms and urodynamic findings,27,28 potentially bypassing the need for urodynamic studies in many patients.29,30 Investigators have also shown that symptoms are not always related to the actual dysfunction causing the incontinence demonstrated on urodynamics.31–35 As mentioned previously, the actual role of urodynamics in case selection and in predicting the continence outcome of surgery is still unknown.36

There are many instances in which a basic clinical evaluation is insufficient. The Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research) published guidelines in 1996 that are still relevant.10 Criteria for further evaluation of incontinence include

uncertain diagnosis and inability to develop a reasonable treatment plan based on the basic diagnostic evaluation

uncertain diagnosis and inability to develop a reasonable treatment plan based on the basic diagnostic evaluation failure to respond or patient dissatisfaction with an adequate therapeutic trial and patient desire to pursuefurther therapy

failure to respond or patient dissatisfaction with an adequate therapeutic trial and patient desire to pursuefurther therapy consideration of surgical intervention, particularly if previous surgery failed or the patient is a high surgical risk

consideration of surgical intervention, particularly if previous surgery failed or the patient is a high surgical risk the presence of other comorbid conditions, such as incontinence associated with recurrent symptomatic urinary tract infection

the presence of other comorbid conditions, such as incontinence associated with recurrent symptomatic urinary tract infectionAdditional testing includes urodynamics but may also include cystoscopy and imaging.

Urodynamics in the Patient with Prolapse

For good urodynamic practices, the reader is referred to the International Continence Society (ICS) publication that reviews current standards for carrying out uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies.37

Urinary Flow Rate

A urinary flow rate is a simple urodynamic test that can provide objective and quantitative measures on both storage and voiding symptoms.37 The curve is either continuous or intermittent. The continuous flow curve is smooth and arc-shaped or a fluctuating (if there are multiple peaks during a period of continuous urine flow). The precise shape of the curve is determined by detrusor contractility, the presence of abdominal straining, and the bladder outlet.38

The parameters of uroflowmetry include the following38:

Maximum flow rate (Qmax) is the maximum measured value of the flow rate after correction for artefacts.

Maximum flow rate (Qmax) is the maximum measured value of the flow rate after correction for artefacts. Voiding time is the total duration of micturition (i.e., including interruptions). If voiding is completed without interruption, voiding time is equal to flow time.

Voiding time is the total duration of micturition (i.e., including interruptions). If voiding is completed without interruption, voiding time is equal to flow time. Average flow rate (Qave) is voided volume divided by the flow time. The average flow should be interpreted with caution if flow is interrupted or if there is a terminal dribble.

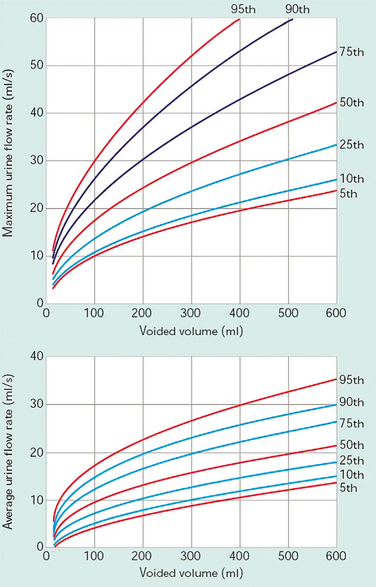

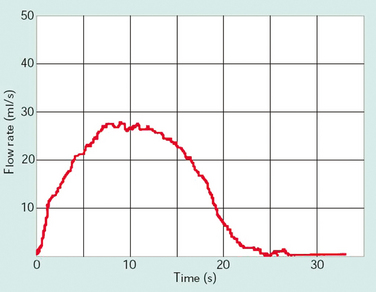

Average flow rate (Qave) is voided volume divided by the flow time. The average flow should be interpreted with caution if flow is interrupted or if there is a terminal dribble.The Liverpool Nomogram (Fig. 57-1) was created in 1989 by Haylen and colleagues, who plotted voided volume against peak flow (Qmax) in 249 normal women.39 Normal peak flowranges between 12 and 30 mL/sec, depending on the voided volume (Fig. 57-2). Average flow rates vary from 6 to 25 mL/sec, with a substantial overlap between normal and abnormal individuals.40 Voiding time varies, from 10 to 20 seconds for a volume of 100 mL to 25 to 35 seconds for a volume of 400 mL. The first half of the urinary volume is rapidly evacuated in the first one third of the total voiding time, and the rest in the remaining two thirds of the voiding period.41 Arbitrary criteria have been set by a number of authors to diagnose voiding difficulty, including peak flow less than 15 mL/sec and residual urine greater than 50 mL with a minimum total bladder volume of 150 mL before the void (volume voided + residual).15,42 The 10th percentile curve of the Liverpool Nomogram has also been identified as a useful discriminant in the diagnosis of voiding difficulties.43

Figure 57-2 Normal flow curve for a voided volume of 350 mL with maximum flow (Qmax) of 27 mL/sec.

(Modified from Lose G: Urethral pressure measurements. In Cardozo L, Staskin D [eds]: Textbook of Female Urology and Urogynaecology. London: Isis Medical Media, 2001, pp 215-226.)

Bottacini and colleagues44 reported that women with stress incontinence void with a lower flow rate than healthy women; however, other investigators have demonstrated the opposite: women with stress incontinence void with a higher flow rate because of the reduced outlet resistance.44

Uroflowmetry findings (peak flow rate, average flow rate, and voided volume) in prolapse have been described to be significantly lower than in normal controls.29 Cystocoele is significantly more frequent in patients with voiding difficulties and abnormal uroflowmetry.35 Valentini and colleagues26 demonstrated a constrictive effect on outflow in women with varying degrees of cystocele. A poor flow rate and elevated residual urine may be associated with large cystoceles.41

In general, an abnormal pattern is generated in the presence of a weak detrusor, abdominal straining, or bladder outlet obstruction. Although urodynamic catheters have less effect on voiding patterns in females than in males, it is still useful to obtain a urinary flow rate on arrival of the patient, to compare with flow data generated during the subsequent urodynamic study. After the initial flow is completed, a postvoid residual can also be determined on introduction of the urodynamic catheters.

Urine Flow Meters

Flow meters are commonly of one of three types: weight, electronic dipstick, or rotating disc.45 The first measures the weight of the collected urine; the second measures the changes in electrical capacitance of a dipstick mounted in the collecting chamber; and the third measures the power required to keep a disc rotating at a constant speed while the urine, which tends to slow it down, is directed toward it. All three can provide high sensitivity and reproducibility of data. A commode chair with uroflow measuring apparatus is shown in Figure 57-3.

Cystometry

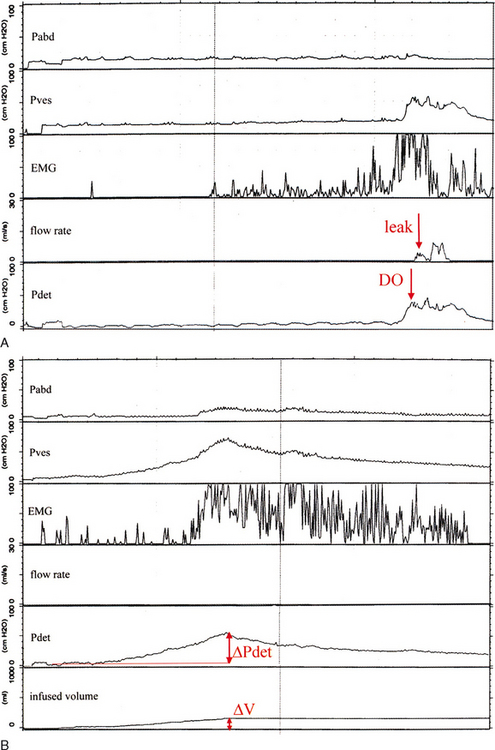

The first part of the filling study is cystometry, the method by which the pressure-volume relationship of the bladder is measured.38 It is used to assess detrusor sensation, capacity, and activity. The detrusor pressure (Pdet) is calculated by subtraction of the abdominal pressure (Pabd), as measured by a balloon in the rectum, vagina, or bowel stoma, from the total intravesical pressure (Pves), as measured by the intravesical catheter. The resulting detrusor pressure reflects the activity and pressure generated by the detrusor muscle alone. Artifacts in the Pdet may be produced by intrinsic rectal contractions.46

Filling rates in the past were described as slow, medium, or fast. Currently, the filling rate is classified as physiologic or nonphysiologic, and the actual rate should be specified.38 Most studies in non-neurologic patients are done with medium fill rates of 50 to 100 mL/min.

Bladder storage function should be noted with bladder sensation (normal; first sensation of filling; first and strong desire to void; increased, reduced, or absent bladder sensation; bladder pain; and urgency), detrusor overactivity, bladder compliance, and capacity.38 The terminology to describe detrusor activity has been standardized by the ICS.38 Detrusor overactivity is characterized by spontaneous or provoked involuntary detrusor contractions during filling. Although an involuntary contraction was originally defined as a minimum pressure rise of 15 cm H2O,47 there is presently no lower limit for the amplitude of an involuntary contraction (Fig. 57-4).38 If leakage is detected in association with an involuntary detrusor contraction, it is termed detrusor overactivity incontinence. Detrusor overactivity can be further characterized into idiopathic and neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Idiopathic detrusor overactivity describes involuntary detrusor contractions of unknown etiology and has replaced the term “detrusor instability.” An involunatary detrusor contraction secondary to an underlying neurologic condition is neurogenic detrusor overactivity, which has replaced “detrusor hyperreflexia.”38

Another type of overactive bladder dysfunction is reduced compliance. Bladder compliance is defined as the change in pressure for a given change in volume. It is calculated by dividing the volume change by the change in detrusor pressure during that change in bladder volume, and it is expressed as milliliters per centimeters of water pressure (see Fig. 57-4B).38 Normal bladder compliance is high, and in the laboratory the normal pressure rise is less than 6 to 10 cm H2O.48 Low bladder com-pliance implies a poorly distensible bladder. The actual numeric values to indicate normal, high, or low compliance have yet to be defined.38

The finding of detrusor overactivity on cystometry is important if it correlates with the clinical condition of the patient. Idiopathic detrusor overactivity has been reported in 30% to 35% of patients with stress incontinence undergoing surgery. It resolves in most such patients after repair and may not have a significant impact on outcome.49,50 Alternatively, if the patient’s symptoms are primarily from bladder overactivity, or other factors predisposing to abnormal bladder behavior are present, the cystometric findings will influence treatment. These predisposing factors include a history of radiation, chronic bladder inflammation, indwelling catheter, chronic infection, chemotherapy, voiding dysfunction after pelvic surgery, and other neurologic conditions.

Urethral Function Tests

The normal urethral closure mechanism maintains a positive urethral closing pressure during bladder filling, even in the presence of increased abdominal pressure. An incompetent mechanism allows leakage in the absence of a detrusor contraction.38 Two urodynamic tests have been used to depict urethral competence: the Valsalva or abdominal leak point pressure (VLPP or ALPP) and the urethral pressure profile (UPP).

Leak Point Pressures

The VLPP is the intravesical pressure that exceeds the continence mechanism resulting in a leakage of urine in the absence of a detrusor contraction.38 The test is performed by a progressive Valsalva maneuver or cough.51 VLPP tests the strength of the urethra. The study is performed with the patient in the sitting or standing position with at least 150 to 200 mL of fluid in the bladder. Historically, a VLPP of less than 60 cm H2O was evidence of significant intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), between 60 and 90 cm H2O suggested a component of ISD, and greater than 90 cm H2O suggested minimal ISD with leakage mainly due to hypermobility.48 Currently, no prospective studies have shown that VLPP less than 60 cm H2O can accurately diagnose ISD. Although the VLPP may be reproducible,52 it has not yet been standardized.5

There are limitations to a VLPP. If the patient’s Valsalva effort is inadequate, urinary leakage may not be seen, and a VLPP measurement cannot be determined. The presence of a catheter in the urethra may prevent incontinence.53 Furthermore, a cystocele or other prolapsing segment may produce inferior pressure on an incompetent urethra that prevents incontinence or falsely elevates the VLPP. If a cystocele is present, the VLPP should be repeated with the prolapse reduced by insertion of a vaginal pack or pessary.

The detrusor or bladder leak point pressure (DLPP) is the lowest detrusor pressure (Pdet) on cystometry at which urinary leakage occurs during bladder filling in the absence of a detrusor contraction or increased abdominal pressure.38 This parameter is used to investigate and monitor patients with neurogenic and low-compliance bladders. In general, patients with a DLPP greater than approximately 25 to 30 cm H2O are at risk for upper tract deterioration from reflux or obstruction.54,55 In these patients, it is necessary to assess compliance as well. A high DLPP indicates poor compliance with urethral obstruction, whereas a low DLPP is seen in patients with incompetent urethras. In order to demonstrate poor compliance in these patients. filling may be done with a Foley catheter to obstruct the outlet.56

Urethral Pressure Profile

Urethral pressure is defined as the fluid pressure needed to just open a closed urethra. The urethral pressure measurements recorded are38

urethral pressure profile (UPP), a graph indicating the intraluminal pressure along the length of the urethra

urethral pressure profile (UPP), a graph indicating the intraluminal pressure along the length of the urethraStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree