Chapter 85 URETHRAL DIVERTICULA

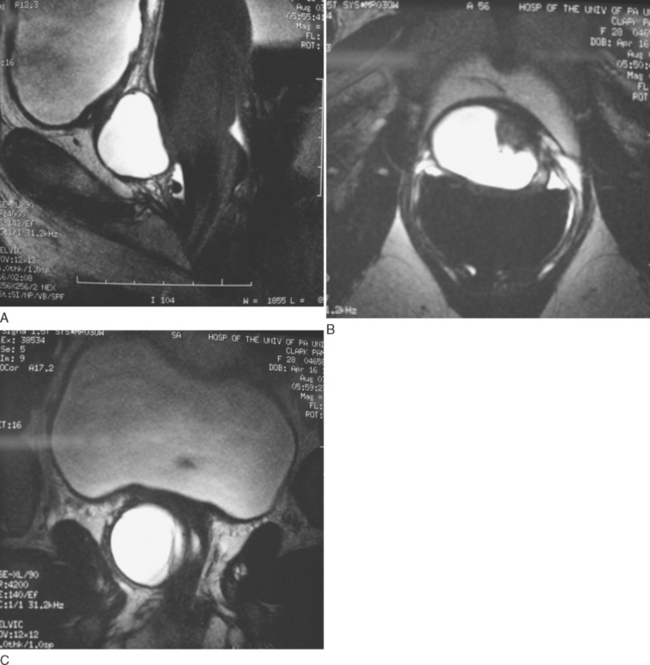

Diverticula of the female urethra present some of the most challenging diagnostic and reconstructive problems in female urology. These cases can be simultaneously fascinating and frustrating. Urethral diverticula have a bewildering variety of clinical manifestations, ranging from completely asymptomatic, incidentally noticed lesions identified on physical examination or radiographs to very debilitating, painful vaginal masses associated with incontinence, stones, or tumors. Anatomic variations between patients and in the location, size and complexity of these lesions ensure that each case is unique (Fig. 85-1).

Although described as early as the 19th century,1 the modern era of diagnosing and treating female urethral diverticula began in 1956 with the advent of positive-pressure urethrography introduced by Davis and Cian.2 Over the next several years, there was a dramatic increase in number of cases of urethral diverticula reported in the literature. Davis and Telinde’s3 series of 121 cases published in 1958 approximately doubled the number of cases reported during the previous 60 years. Development of adjuvant imaging techniques such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during the past 3 decades has contributed greatly to understanding of urethral diverticula. With the expanding use of these imaging modalities, the diagnosis and evaluation of this condition continues to evolve. After the diagnosis is confirmed, definitive therapy often consists of operative excision and reconstruction. Successful surgical excision and reconstruction requires a detailed knowledge of the relevant operative anatomy, adherence to basic surgical tenets, and an ability to be creative and sometimes even improvisational in the operating room.

ANATOMY OF THE FEMALE URETHRA

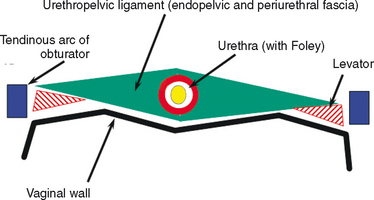

The normal female urethra is a musculofascial tube approximately 3 to 4 cm long. It extending from the bladder neck to the external urethral meatus, and it is suspended from the pelvic side wall and pelvic fascia (i.e., tendinous arc of the obturator muscle) by a sheet of connective tissue called the urethropelvic ligament. The urethropelvic ligament is composed of two layers of fused pelvic fascia that extend toward the pelvic side wall bilaterally (Fig. 85-2). This structure can be considered to have an abdominal side (i.e., endopelvic fascia) and a vaginal side (i.e., periurethral fascia). Within and between these two leaves of fascia lies the urethra.

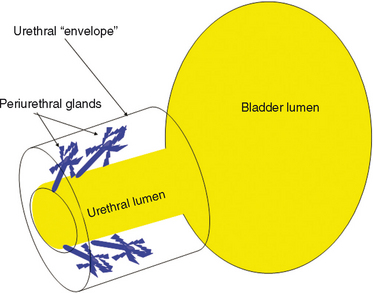

The urethral lumen is lined by an epithelial layer that is a transitional cell type proximally and a nonkeratinized stratified squamous cell type distally. The urethra can be considered to be a rich, vascular, spongy cylinder surrounded by an envelope of consisting of smooth and skeletal muscle and fibroelastic tissue.4 Within the thick, vascular lamina propria-submucosal layer are the periurethral glands (Fig. 85-3). These tubuloaveolar glands exist over the entire length of the urethra posterolaterally, but they are most prominent over the distal two thirds, with most glands draining into the distal one third of the urethra. Skene’s glands are the largest and most distal of these glands. These glands drain outside the urethral lumen, lateral to the urethral meatus. Most acquired female urethral diverticula originate from pathologic processes involving the periurethral glands.

Arterial inflow to the urethra derives from two sources. The proximal urethra has a similar blood supply as the adjacent bladder, whereas the distal urethra derives its blood supply from the terminal branches of the inferior vesical artery through the vaginal artery, which runs along the superior lateral aspect of the vagina. Lymphatic drainage of the female urethra is to the sacral lymph nodes, internal iliac nodes, and inguinal lymph nodes. Innervation to the female urethra is from the pudendal nerve (S2 to S4), and afferents from the urethra travel by means of the pelvic splanchnic nerves.

URETHRAL DIVERTICULA

Pathophysiology and Etiology

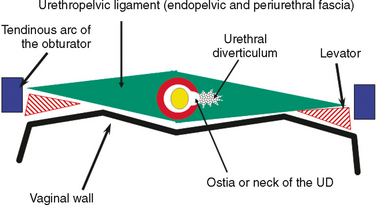

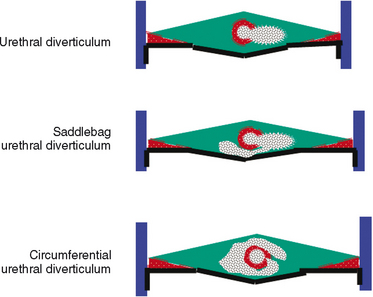

As conceptualized by Raz and colleagues,4 a urethral diverticulum represents an epithelialized cavity dissecting within the confines of the fascia of the urethropelvic ligament. This defect is often an isolated cystlike appendage with a single, discreet connection to the urethral lumen, called the neck or ostia (Fig. 85-4). However, complicated anatomic patterns may exist, and in certain cases, the urethral diverticula may extend partially (i.e., saddlebag urethral diverticula) around the urethra, anterior to the urethra,5 or circumferentially about the urethra (Fig. 85-5).6

The exact origin of urethral diverticula is unknown. A major debate in the earlier part of the 20th century focused on whether urethral diverticula were congenital or acquired lesions.7–9 Although this condition exists in children, it may represent a different clinical entity from adult female urethral diverticula. Scattered reports of congenital urethral diverticula in female infants have been described.10 Marshall11 reported five cases of urethral diverticula in young females, and three diverticula underwent spontaneous regression. Congenital anterior urethral diverticulum is a well-described entity in boys,12–14 but this is considered to be a different clinical entity from urethral diverticula in the female. Congenital Skene’s glands cysts have been reported15,16 but are considered to be rare. Diverticula in the pediatric population have been attributed to a number of congenital anomalies, including an ectopic ureter draining into a Gartner’s duct cyst and a form fruste of urethral duplication.17–19 Most urethral diverticula are likely to be acquired and are diagnosed in female adults. In two large series of urethral diverticula, there were no patients reported who were younger than 10 years old,20,21 arguing against a congenital origin for these lesions. Although it is possible that there exists a congenital defect in patients that results in or represents a precursor to urethral diverticula that becomes symptomatic only later in life, it remains unproven.

There are many theories regarding the formation of acquired urethral diverticula. For many years, acquired urethral diver-ticula were thought to be most likely caused by trauma from vaginal childbirth.22 It was postulated that mechanical trauma during vaginal delivery resulted in herniation of the urethral mucosa through the muscular layers of the urethra, with the subsequent development of a urethral diverticula. However, 20% to 30% of patients in some urethral diverticula series are nulliparous,23,24 which may significantly discount parity as a risk factor. Trauma with forceps delivery, however, has been reported to cause urethral diverticula,25 as has the endoscopic injection of collagen.26

The periurethral glands are the probable site of origin of acquired urethral diverticula.4 Huffman’s27 anatomic work with wax models of the female urethra were critical to the early theories regarding the pathophysiology of urethral diverticula and the involvement of the periurethral glands. By reviewing 10-μm transverse sections, he refuted earlier anatomic descriptions of the glandular anatomy of the female. He characterized the periurethral glands as located primarily dorsolateral to the urethra, arborizing proximally along the urethra and draining into ducts located in the distal one third of the urethra (see Fig. 85-3). He found that periductal and interductal inflammation was common. In support of these observations and an infectious (acquired) cause of urethral diverticula, in more than 90% of urethral diverticula cases, the ostium is located posterolaterally in the middle or distal urethra, which corresponds to the location of the periurethral glands.28,29

Although there are probably other factors that facilitate the initiation, formation, or propagation of urethral diverticula, infection of the periurethral glands seems to be the etiologic factor in most cases. Peters and Vaughn30 found a strong association between concurrent or previous infection with Neisseria gonorrhea and urethral diverticula. However, the initial infection and especially subsequent reinfections may be caused by a variety of organisms, including E. coli, other coliform bacteria, and vaginal flora.

Urethral diverticula have been historically attributed to recurrent infection of the periurethral glands with obstruction, sub-urethral abscess formation, and subsequent rupture of these infected glands into the urethral lumen. Continual filling and pooling of urine in the resultant cavity may result in stasis, recurrent infection, and eventual epithelialization of the cavity, forming a permanent urethral diverticulum. This concept was first popularized by Routh31 more than a century ago, and it has become the most widely accepted theory regarding the formation of female urethral diverticula. Reinfection, inflammation, and recurrent obstruction of the neck of the cavity are theorized to result in patients’ symptoms and in enlargement of the diverticulum. This proposed pathophysiology appears to adequately explain the anatomic location and configuration of most urethral diverticula and is supported by the work of Huffman.27 However, Daneshgari and colleagues32 have reported noncommunicating urethral diverticula diagnosed by MRI. Whether this lesion represents a forme fruste of urethral diverticula or simply an obstructed urethral diverticula ostium is unclear.

Raz and colleagues4 formulated a modern hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of urethral diverticula through extensive clinical experience with this entity, including the diagnosis, imaging, and surgical repair of urethral diverticula. These investigators propose that acquired urethral diverticula result from infection and obstruction of the periurethral glands. These glands are normally found in the submucosal layer of the spongy tissue of the distal two thirds of the urethra. Repeated infection and abscess formation in these obstructed glands eventually result in enlargement and expansion. Initially, the expanding mass displaces the spongy tissue of the urethral wall and then enlarges to disrupt the muscular envelope of the urethra. This results in herniation into the periurethral fascia. The enlarging cavity can then expand and dissect within the leaves of the periurethral fascia and urethropelvic ligament. This expansion occurs most commonly ventrally, resulting in the classic anterior vaginal wall mass palpated on physical examination in some patients with urethral diverticula. However, the lesions may also expand laterally or even dorsally about the urethra. Eventually, the abscess cavity ruptures into the urethral lumen, resulting in the communication between the urethral diverticula and the urethral lumen. An appreciation of the anatomy and pathophysiology of urethral diverticula is important in understanding the surgical approach to the excision and reconstruction of these lesions.

Prevalence

Moore33 stated that urethral diverticula as an entity is “found in direct proportion to the avidity with which it is sought.” Although no longer considered a rare lesion, fewer than 100 cases of urethral diverticula were reported in the literature before 1950. With the development of sophisticated imaging techniques, including positive-pressure urethrography in the 1950s, the diagnosis of urethral diverticula became increasingly common.

The true prevalence of female urethral diverticula is unknown, but it is reported to occur in up to 1% to 6% of adult females in some series. Determining the true prevalence of urethral diverticula would require appropriate screening and imaging of a large number of symptomatic and asymptomatic adult female subjects in a primary care setting, which has not been done. Bruning34 found urethral diverticula in 3 of 500 female autopsy specimens. In 1967, Andersen reported the results of positive-pressure urethrography on 300 women with cervical cancer but without lower urinary tract symptoms and found urethral diverticula in 3%.35 Aldridge36 reported a prevalence of urethral diverticula in 1.4% of women presenting with incontinence and related symptoms. Stewart37 found urethral diverticula in 16 of 40 highly symptomatic females investigated with positive-pressure urethrography. Endorectal coil MRI was performed on 140 consecutive female patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, and the incidence of urethral diverticula was approximately 10%.38 However, this represented a series of symptomatic females at a tertiary referral center, which probably did not reflect the general population.

Some series have suggested a definite racial predilection, with blacks being as much as six times as likely to develop urethral diverticula as their white counterparts.20 The reasons for this racial distribution is not well understood. It has not been confirmed in some modern case series, and it may reflect referral bias at the urban academic centers in the original reported series.39

Diverticular Anatomy

Most commonly, urethral diverticula represent an epithelialized cavity with a single connection to the urethral lumen. The size of the lesion may vary from only a few millimeters to several centimeters. The size may vary over time because of inflammation and intermittent obstruction of the ostia with subsequent drainage into the urethral lumen.

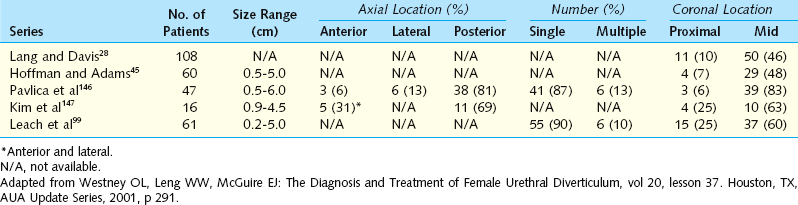

The epithelium of urethral diverticula may be columnar, cuboidal, stratified squamous, or transitional. In some cases, the epithelium is absent, and the wall of the urethral diverticula consists of only fibrous tissue. These lesions are found within the periurethral fascia bordered by the anterior vaginal wall ventrally. Urethral diverticula are most often located in the sagittal plane, and they are centered at the level of the middle third of the urethra, with the luminal connection or ostia located posterolaterally. They may extend distally along the vaginal wall almost to the urethral meatus or proximally up to and beyond the bladder neck, underneath the trigone of the bladder (Fig. 85-6). A bewildering array of configurations can be identified on imaging and at surgical exploration (Table 85-1). In the axial plane, the urethral diverticula cavity may extend laterally along the urethral wall, and in some cases, they may extend around to the dorsal side of the urethra or wrap circumferentially around the entire urethra. Urethral diverticula may be bilobed (i.e., dumbbell shaped), extending across the midline in a so-called saddlebag configuration (see Fig. 85-5). Multiple loculations are not uncommon, and at least 10% of patients have multiple urethral diverticula at presentation. Various degrees of sphincteric compromise may exist because of the location of diverticulum relative to the proximal and distal urinary sphincter mechanisms. This is a consideration for surgical repair.

Presentation

Most patients with urethral diverticula present between the third and seventh decade of life.7,23,33,40,41 The presenting symptoms and signs of patients with urethral diverticula are protean (Box 85-1). The classic presentation of urethral diverticula has been described historically as the three Ds: dysuria, dyspareunia, and dribbling (postvoid). However, individually or collectively, these symptoms are neither sensitive nor specific for urethral diverticula. Although presentation is highly variable, the most common symptoms are irritative (e.g., frequency, urgency) lower urinary tract symptoms, pain, and infection.20,21,30,42 Dyspareunia is reported by 12% to 24% of patients.20,21 Approximately 5% to 32% of patients complain about postvoid dribbling.20,23 Recurrent cystitis or urinary tract infection is a frequent presentation in one third of patients,20,23 likely due to urinary stasis in the urethral diverticula. Multiple bouts of recurrent cystitis should alert the clinician to the possibility of a urethral diverticulum. Other complaints include pain, a vaginal mass, hematuria, vaginal discharge, obstructive symptoms or urinary retention, and stress or urge incontinence. Up to 20% of patients diagnosed with urethral diverticula may be completely asymptomatic. Patients may present with complaints of a tender or nontender anterior vaginal wall mass, which on gentle compression may reveal retained urine or purulent discharge through the urethral meatus. Although spontaneous rupture of these lesions is rare, urethrovaginal fistula may result under these circumstances.43

Because many of the symptoms associated with urethral diverticula are nonspecific, patients may be misdiagnosed and treated for years for a number of unrelated conditions before the diagnosis of urethral diverticula is made. This may include therapies for interstitial cystitis, recurrent cystitis, vulvodynia, endometriosis, vulvovestibulitis, and other conditions. In one series of 46 consecutive women eventually diagnosed with urethral diverticula, the mean interval from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 5.2 years.44 In this series, women consulted with an average of nine physicians before the definitive diagnosis was made, despite the fact that 52% of women had a palpable mass on examination. This underscores the importance of a baseline level of suspicion and a thorough pelvic examination in female patients complaining of lower urinary tract symptoms or other symptoms that may be associated with urethral diverticula.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Physical Examination

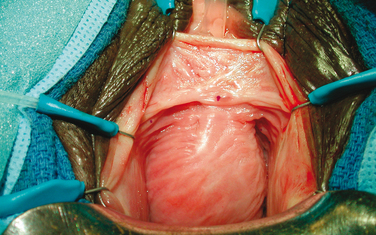

During physical examination the anterior vaginal wall should be carefully palpated for masses and tenderness. The location, size, and consistency of suspected urethral diverticula should be recorded. Most urethral diverticula are located ventrally over the middle and proximal portions of the urethra, corresponding to the area of the anterior vaginal wall 1 to 3 cm inside the introitus (Fig. 85-7). However, urethral diverticula also may be located anterior to the urethra or extend partially or completely around the urethral lumen. These particular configurations may have significant implications when undertaking surgical excision and reconstruction. Urethral diverticula may extend proximally toward the bladder neck. The urethral diverticula may produce distortion of the bladder outlet and trigone of the bladder on cystoscopy or on radiographic imaging, and special care should be taken during surgical excision and reconstruction because of concerns about intraoperative bladder and ureteral injury and the potential for development of postoperative voiding dysfunction and urinary incontinence. More distal vaginal masses or perimeatal masses may represent other lesions, including abnormalities of Skene’s glands. The differentiation between these lesions sometimes cannot be made on the basis of a physical examination alone and may require additional radiologic imaging. A particularly hard anterior vaginal wall mass may indicate a calculus or cancer within the urethral diverticula, and it mandates further investigation. During physical examination, the urethra may be gently stripped or milked distally in an attempt to express purulent material or urine from within the urethral diverticula cavity. Although often described for the evaluation of urethral diverticula, this maneuver is not successful in producing the diagnostic discharge through the urethral meatus in most patients.39

Urine Studies

Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed. The most common organism isolated in patients with urethral diverticula is Escherichia coli. However, other gram-negative enteric flora and Neisseria gonorrhea, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus are often present.3,45 A sterile urine culture does not exclude infection because these patients are often on antibiotic therapy at presentation. For patients with irritative symptoms or when a malignancy is suspected, urine cytology can be performed.

Cystourethroscopy

Cystourethroscopy is performed in an attempt to visualize the urethral diverticular ostia and to rule out other causes of the patient’s lower urinary tract symptoms. A specially designed female cystoscope can be helpful in evaluating the female urethra. The short beak maintains the discharge of the irrigation solution immediately adjacent to the lens, which aids in distention of the relatively short (compared with the male) urethra, permitting improved visualization. It may also be advantageous to compress the bladder neck while simultaneously applying pressure to the diverticular sac with an assistant’s finger. Luminal discharge of purulent material can often be seen with this maneuver or with simple digital compression of the urethral diverticula during urethroscopy. The urethral diverticular ostium is most often located posterolaterally at the level of the mid-urethra, but it can be very difficult to identify in some patients. The success rate in identifying a diverticular ostium on cystourethroscopy is highly variable and is reported to be between 15% and 89%.20,23,39 Patients with urethral diverticula are often highly symptomatic, and endoscopic examination can be difficult to initiate or complete. A positive examination result may help in surgical planning, but the failure to locate an ostium on cystourethroscopy should not influence the decision to proceed with further investigations or surgical repair.

Urodynamics

For patients with urethral diverticula and urinary incontinence or significant voiding dysfunction, a urodynamic study can be helpful.46–48 Urodynamics may document the presence or absence of stress urinary incontinence before repair. Approximately 50% of women with urethral diverticula are found to have stress urinary incontinence on urodynamic evaluation.23,49 A video urodynamic study combines a voiding cystourethrogram and a urodynamic study, consolidating the diagnostic evaluation and decreasing the number of required urethral catheterizations during the patient’s clinical workup. For patients undergoing surgery for urethral diverticula with coexistent, symptomatic stress urinary incontinence demonstrated on physical examination or by urodynamic study or for those found to have an open bladder neck on preoperative evaluation, concomitant anti-incontinence surgery can be offered. Many investigators have described successful concomitant repair of urethral diverticula and stress incontinence in the same operative setting.23,49–51 Alternatively, on urodynamic evaluation, a small number of patients may have evidence of bladder outlet obstruction due to the obstructive or mass effects of the urethral diverticula on the urethra. Stress urinary incontinence may coexist with obstruction,52 but both conditions can be treated successfully with a carefully planned and executed operation. Urethral pressure profilometry has also been used by some physicians to assess or diagnose patients with urethral diverticula by noticing a biphasic pattern at the level of the lesion during the study.47,48,53

Imaging

Positive-Pressure Urethrography, Voiding Cystourethrography, and Intravenous Urography

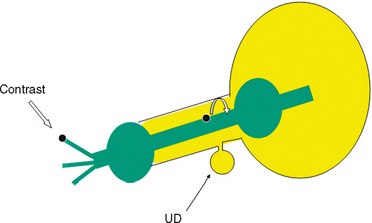

Classically, double-balloon PPU had been considered to be the best study for the diagnosis and assessment of female urethral diverticula.2,21,23,54 With this technique, a highly specialized catheter with two balloons separated by several centimeters is inserted into the female urethra (Fig. 85-8). This catheter contains a channel within the catheter that exits through a side hole between the two balloons. One balloon is positioned adjacent to the external urethral meatus, and the other balloon is situated at the bladder neck. Both balloons are inflated, sealing the urethral lumen. Contrast is then infused through the channel under slight pressure, distending the urethral lumen between the two balloons and forcing contrast into the urethral diverticula, thereby opacifying the cavity. This highly specialized study provides outstanding images of the urethra and urethral diverticula, and unlike VCUG, it does not depend on the patient successfully voiding during the study. However, PPU is not widely performed clinically. It is a complicated study requiring a very specific type of modified urethral catheter and expertise in the performance and interpretation of the study by the radiologist. It is invasive, requiring catheterization of the urethra, and in the setting of acute inflammation commonly seen with female urethral diverticula, it can cause considerable patient discomfort and distress. Noncommunicating urethral diverticula32 and loculations within existing urethral diverticula cannot be visualized with PPU because the contrast does not enter and fill these areas in the absence of a connection to the urethral lumen.

As an alternative to PPU, VCUG may provide excellent imaging of urethral diverticula (Fig. 85-9). It is widely available and is a familiar diagnostic technique to most radiologists. Sensitivity for urethral diverticula with this technique varies from 44% to 95%.23,55

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree