Chapter 62 TRANSABDOMINAL PARAVAGINAL CYSTOCELE REPAIR

HISTORY

In 1909, Dr. George White described a novel idea for the etiology of cystoceles based on his work with cadaver dissection.1 He first described the supportive attachments of the vagina. He next illustrated how lateral detachment of the pubocervical fascia from the arcus tendineous fascia pelvis, or white line, results in cystocele. He also outlined the critical steps for the transvaginal paravaginal repair of these types of cystoceles. It is clear after reading the peer review section following his article that his idea was unique at the time and that a fundamental understanding of the three-dimensional relationship of female pelvic anatomy was lacking.

Three years later, White submitted a treatise in which he reviewed the three theories of that period regarding the etiology of cystocele2:

White again described his technique for vaginal paravaginal repair for the management of cystocele. He acknowledged that the vaginal approach was more difficult because of limited visibility, but he believed that the surgical approach for treatment of cystocele should remain vaginal because of the then-widespread practice of concurrent perineorrhaphy. He conceded that, “to incise the peritoneum at the side of the bladder, push the bladder aside until the white line comes into view, then by the aid of an assistant’s finger in the vagina, suture the anterior lateral side of the vagina to the white line, and close the peritoneum” may be “the easiest and simplest way to accomplish this.”2 However, he believed that the abdominal approach was seldom indicated, unless the patient suffered from procidentia. In that case, the patient would be best served by concurrent restoration of the broad and uterosacral ligaments.

White’s papers were largely forgotten for the next 70 years. Historically, it is not clear why his ideas were not readily accepted. Perhaps it was because the approach was difficult to perform, or because his peers lacked a proficient understanding of the lateral fascial defects and their role in anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Even more significant was the almost simultaneous publication of Howard Kelly’s treatise on cystocele, its repair, and the treatment of stress incontinence.3 The Kelly plication is straightforward in its conceptualization and technically easier to perform. Failures of the Kelly plication in a large number of cystocele repairs led to a series of “new” techniques for the repair of lateral anterior wall defects, including work by John C. Burch and Cullen Richardson.4,5

In 1961, Burch reported his experience with colposuspension in the treatment of stress incontinence. He attached the paravaginal fascia to the white line of the pelvis in the first seven of his patients. He wrote that the maneuver “produced a most satisfactory restoration of the normal anatomy of the bladder neck…and a surprising correction of most of the cystocele…overcoming the anterior cystocele involving the neck of the bladder, but also the posterior cystocele involving the base of the bladder.”4 Despite such positive results with correction of both urethral hypermobility and bladder prolapse, Burch believed that the white line held sutures poorly and therefore sought another fixation point. Subsequently, he chose Cooper’s ligament as the point of fixation.

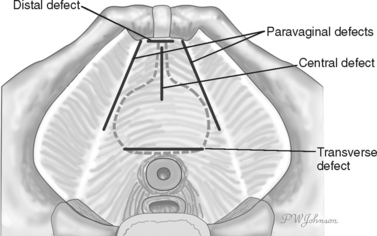

In 1976, Richardson, Lyon, and Williams published a “new” look at pelvic relaxation. They outlined the technique for transabdominal paravaginal repair—echoing the descriptions of White and Burch. They also identified the four areas of defects or breaks in the pubocervical fascia, in their order of occurrence5:

ANATOMY

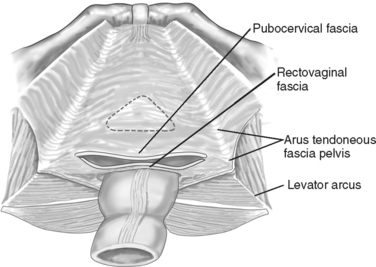

The pubocervical fascia (or endopelvic fascia), a trapezoid-shaped, fibromuscular band of tissue, supports the urethra, bladder, and uterus anteriorly (Fig. 62-2). Its lateral border extends from a point just anterior to the ischial spines, along the arcus tendineous fascia pelvis or white line, to the pubic ramus anteriorly. Posteriorly, it reaches the cervix or vaginal cuff at the level of the base of the broad ligament and cardinal-uterosacral ligaments and reaches across toward the ischial spines.

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse results from herniation of the pelvic organs normally supported by the pubocervical fascia into the vaginal lumen. Many gynecologists believe that identification and repair of defects in this fascia are essential to achieve successful anterior colporrhaphy. However, the existence of fascial tissue between the vagina and bladder or vagina and rectum has never been proven histologically.6–9 To examine the histology of surgical fascia used during anterior colporrhaphy, to compare it to recto-vaginal fascia, and to determine the consistency with which this tissue is diagnosed surgically, Farrell and his colleagues examined the fascia of women who were scheduled to undergo a primary surgical correction of pelvic organ prolapse.9 Biopsies taken of surgically identified pubocervical fascia and rectovaginal fascia during colporrhaphy failed to identify a distinct fascial layer. Instead, histologic examinations of tissue identified as fascia intraoperatively showed it to be indistinguishable from deep vaginal wall connective tissue.

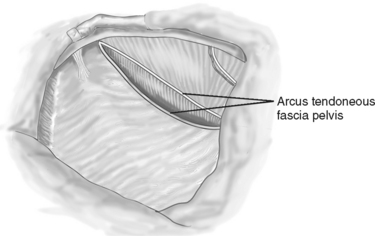

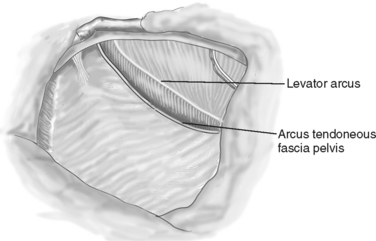

It is possible to have both central and lateral defects concurrently. Lateral detachment of the pubocervical fascia may occur if the entire arcus pulls away from the pelvic sidewall (Fig. 62-3). Alternatively, the entire arcus may remain attached to the sidewall while the pubocervical fascia pulls away.27 Finally, the arcus could split, with a portion remaining attached to the pubocervical fascia medially and another portion remaining attached to the pelvic sidewall laterally (Fig. 62-4).

Figure 62-3 The arcus tendineous fascia pelvis has separated entirely off the pelvic sidewall.

(From Richardson AC: Operative Techniques in Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1996.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree