Chapter 34 The Dilated Pancreatic Duct

The pancreas arises from the fusion of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds. The dorsal pancreatic bud gives rise to the pancreatic body and tail and the ventral pancreatic bud gives rise to the pancreatic head and uncinate process. The main pancreatic duct (or duct of Wirsung) forms when the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds fuse at the genu (or neck), with the pancreatic drainage emptying via the major papilla. A remnant of the dorsal pancreatic bud that is in continuity with the minor papilla is called the duct of Santorini. In patients with pancreas divisum, occurring in roughly 10% of the population, the major route of pancreatic drainage is through the duct of Santorini and the minor papilla rather than the major papilla. Refer to Chapter 32 for more details on pancreas divisum and other pancreatic anomalies.

The average dimension of the pancreatic duct varies from patient to patient and with respect to the location within the pancreas. In general, the main pancreatic duct diameter is approximately 3 to 4 mm in the head, 2 to 3 mm in the body, and 1 to 2 mm in the tail. Pancreatic duct dilation would then refer to a ductal dimension that exceeds the accepted upper limit of normal at each anatomic section. Causes for dilation of the pancreatic duct can broadly be divided into those associated with benign conditions and those associated with malignant or premalignant conditions (Box 34.1).

Box 34.1

Differential Diagnosis of the Dilated Pancreatic Duct

Benign

Several clinical and autopsy studies have suggested that the pancreatic duct likely dilates with age in the absence of underlying pancreatic pathology. In one autopsy study of 112 patients without known pancreatic disease, 18 patients (16%) had pancreatic duct diameters greater than 4 mm. Interestingly, a significantly higher proportion of patients (40%) had dilated pancreatic side branches, which were typically seen in association with inspissated eosinophilic deposits in the side branches.1 Hastier and colleagues compared pancreatograms obtained at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) from 105 subjects older than 70 years of age with those obtained from a control group of patients less than 50 years of age.2 Subjects with pancreatic pathology were excluded from both cohorts. They found that mean main pancreatic duct diameter in the head of the pancreas was 2 mm wider (5.3 mm compared to 3.3 mm, p <0.05) in the older cohort and that 20% of the subjects in the elderly group had pancreatic duct diameters that were more than 2 standard deviations above normal. In a prospective endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) study of age-related changes in the pancreas, patients older than 60 years of age had wider pancreatic ducts in the head of the pancreas (median diameter in mm; interquartile range = 2.9 [2.2 to 3.5]) than did patients less than 40 years of age (2.0 [1.6 to 2.2]).3 Similarly, pancreatic duct diameters in the pancreatic body were greater in patients older than 60 years (1.8 [1.3 to 2.1]) compared to patients younger than 40 years (1.5 [1.2 to 2.0]) while the duct diameter in the tail of the pancreas did not differ significantly between these two groups.

Evaluation

Clinical

If the patient is truly asymptomatic it may influence the decision regarding further treatment or investigation. This is particularly true if the patient is of an advanced age or has significant comorbidities, wherein a potential endoscopic procedure or surgical resection may not affect the natural history of the disease or improve the length or quality of life. In contrast, since one third of patients with isolated pancreatic duct dilation without chronic pancreatitis are diagnosed with an underlying pancreatic malignancy, it is generally prudent to obtain further diagnostic information in the majority of patients.4

Laboratory Evaluation

Serum amylase and lipase: These values can be elevated in the setting of pancreatitis, pancreatic cystic lesions, and pancreatic neoplasms. Amylase and lipase levels may also be increased in the absence of pancreatic disease in the setting of renal insufficiency, intestinal injury, or gastrointestinal ischemia. Nevertheless, a serum lipase greater than three times the upper limit of normal is a reliable diagnostic criterion for acute pancreatitis in the appropriate clinical setting. In patients with chronic pancreatitis, normal levels of amylase and lipase do not exclude a flare of acute pancreatitis. Persistent but mild elevations can be seen in chronic pancreatitis.

Fecal fat: Elevated levels of fecal fat imply an element of fat malabsorption, typically from exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. This can be tested in a qualitative manner as a one-time stool test. A timed quantitative 72-hour cumulative collection can be used as a screening or confirmatory test. The upper level of normal is a measurement of >7 g of fat per 24-hour period.

Fecal elastase-1 and chymotrypsin: The fecal elastase-1 test is used to measure the concentration of elastase-3B enzyme in the stool, a zymogen that is secreted by the pancreas. Levels in the stool of <200 µg/g of stool suggest exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Serum CA 19-9: CA 19-9 has limited utility as a screening test and is employed more effectively as a surveillance test for disease recurrence in those patients in whom levels are high prior to treatment. Serum CA 19-9 lacks specificity for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and can be elevated in a variety of nonpancreatic cancers, including colon cancer, hepatoma, and gastric cancer, as well as in noncancerous disease states, including acute and chronic pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis with or without cholangitis, cirrhosis of the liver, and biliary obstruction of any cause.5 The presence of hyperbilirubinemia is particularly confounding in the interpretation of elevated serum CA 19-9 levels. In one retrospective study serum CA 19-9 was elevated in 61% (25 of 61) of subjects ultimately found to have obstructive jaundice from benign causes.6 The same study showed that normalization or a significant drop in CA 19-9 levels (to less than 90 U/mL) after biliary drainage was highly suggestive of a benign etiology. It is possible that alternative assays for CA 19-9 may improve specificity in the future7 but at the present time this marker should be considered adjunctive information in the particular setting where pancreatic ductal dilation is identified, as a markedly high level (>1000 U/mL) would argue for a malignant etiology. For a detailed discussion of the utility and limitations of CA 19-9 in the evaluation of patients with suspected pancreatic cancer, the reader is referred to two comprehensive reviews on the topic.8,9

Fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) with measurement of fluid CEA level has been used to help guide the diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions (including mucinous cystic neoplasms and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms) by providing information that is complementary to clinical and imaging data. As CEA is secreted in high levels from mucinous cystic lesions as opposed to serous cystadenomas, it is thought that higher levels of CEA suggest a higher likelihood of mucinous neoplasm. Studies have shown that fluid CEA levels >200 ng/mL are highly sensitive and specific for mucinous cystic lesions but cannot definitively differentiate between benign and malignant lesions.10 The diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) in a patient with an isolated dilated pancreatic duct is typically made using imaging results in combination with clinical history, although the use of fluid CEA level obtained via EUS-FNA as well as endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) has been described.11–13

Imaging and Endoscopy

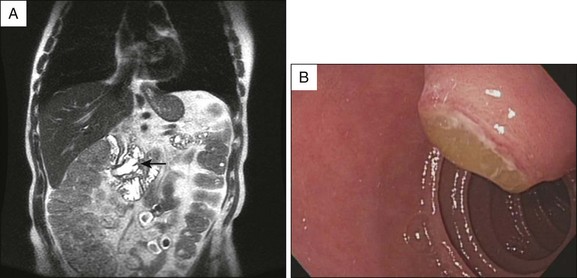

Radiologic studies provide a noninvasive means to further assess the patient with a dilated pancreatic duct. A pancreatic protocol computed tomography (CT) scan includes fine (1 to 3 mm) cuts through the pancreas with timed arterial contrast injection to provide higher resolution imaging of the pancreas. Even when traditional abdominal CT identifies a dilated pancreatic duct, a pancreatic protocol CT can add a significant amount of information as to the nature of the dilation. Similarly, direct visualization of the pancreatic orifice may reveal a patulous opening diagnostic for main duct IPMN (Fig. 34.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree