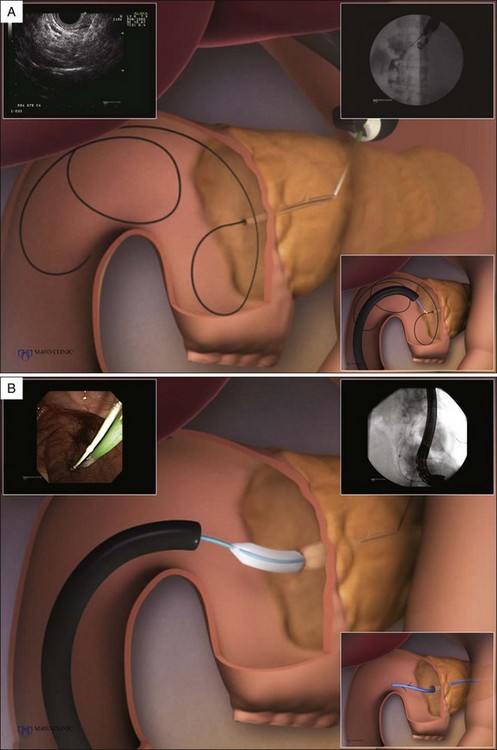

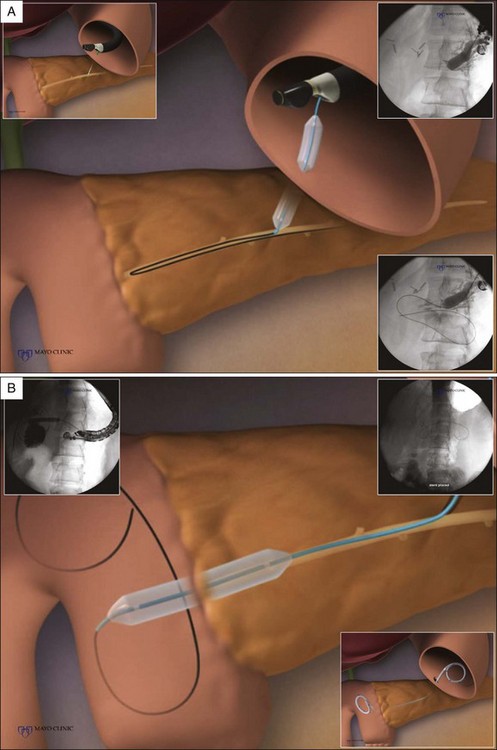

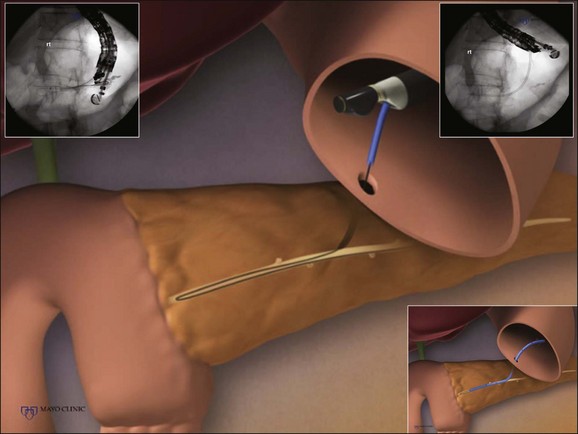

Chapter 31 Endoscopic Ultrasound–Assisted Access to the Pancreatic Duct

Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) is the method most commonly employed to access the main pancreatic duct (MPD) and is occasionally performed for diagnostic purposes and routinely performed for therapeutic purposes. Historically, percutaneous and surgical approaches were the only options available for patients in whom access could not be achieved via ERP. An emerging alternative is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–assisted pancreatic access and drainage. While EUS was introduced nearly 30 years ago as a diagnostic imaging modality, the development of linear instruments allowed for tissue acquisition.1,2 This subsequently led to the development of EUS-guided therapeutic interventions including celiac blockade and neurolysis,3–5 pancreatic fluid collection drainage,6–9 cholecystenterostomy10 and delivery of chemotherapy, radioactive seeds, and gene therapy.11,12 The concept of combining ERP with interventional EUS technology led to the first report in 1995 of EUS-guided pancreatography for a patient who required pancreatic duct stone removal following pancreaticoduodenectomy.13 The continued need to develop less invasive alternatives to surgical and interventional radiological therapies has further driven the development of EUS-guided methods for pancreatic intervention.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.