Chapter 41 Biliary Surgery Adverse Events Including Liver Transplantation

The treatment of late strictures will not be discussed in detail, as this particular topic is described in Chapter 40.

Physiological Basis of ERCP Techniques in the Treatment of Biliary Surgery Adverse Events

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Decreasing Intrabiliary Pressure

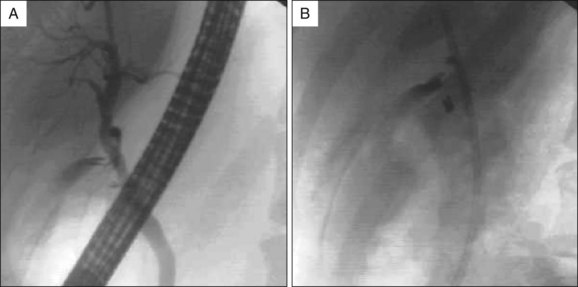

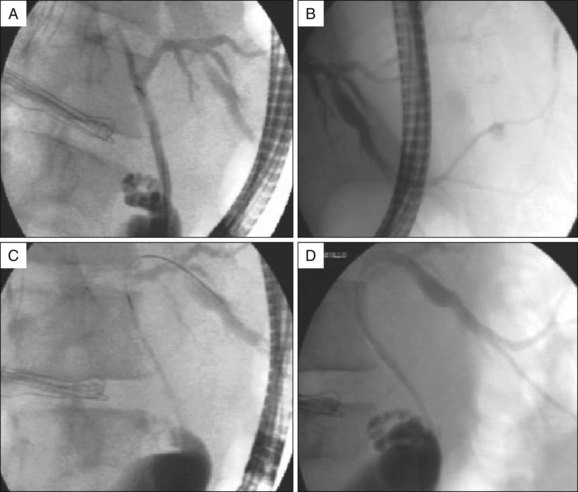

The first aim of endoscopic therapy is to decrease or abolish the tone of the sphincter of Oddi, which diverts bile flow away from the leak site. This can be achieved with biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES). Since ES does cut the sphincter completely, we recommend transpapillary stent placement to bypass residual sphincter muscle (Fig. 41.1). Stent placement alone is preferred in patients at high risk for post-ES bleeding.

Bypassing Bile Flow

In addition to reducing the pressure, the stent diverts bile toward the papilla and reduces flow through the leak site. This contributes indirectly to the closure of the leak (Fig 41.2). Considering the low morbidity of plastic stents, we recommend the combined use of ES and stent placement to maximally reduce intrabiliary pressure.

Traditionally, plastic stents have been used but covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) have recently been used. Bioabsorbable self-expandable stents may be an option in the future and would eliminate the need for endoscopic removal.1

Nasobiliary tubes can also be used as an alternative to stent placement in the treatment of biliary leaks after LC. Advantages include avoidance of sphincterotomy, easy removability, and ability to obtain interval tube cholangiograms to assess leak closure.2 However, because of patient discomfort and potential for dislodgement, nasobiliary tubes are not routinely used.

Sealing the Leak

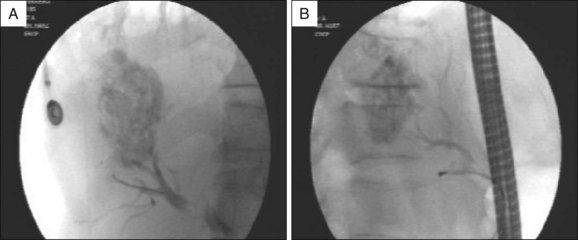

In patients with biliopleural fistulae, negative pressure pulls bile into the thoracic cavity. Application of sealants may be necessary to obtain prompt control of the leak. ERCP can allow application of sealants to close the leak.3,4 However, because of the theoretical risk of glue pulmonary embolism, we reserve this treatment for highly selected cases of biliopleural fistulae and bilioperitoneal fistulae refractory to combined treatment with ES and plastic stent placement (Fig. 41.3).

Stricture Dilation

Benign biliary strictures require dilation followed by multiple stent placements and exchanges. This approach is described in detail in Chapter 40 and offers a minimally invasive alternative to choledochojejunostomy and hepaticojejunostomy in the management of postoperative biliary strictures.5

Occlusion of plastic stents due to biofilm accumulation leads to the need for repeated exchanges, though data show that the interval to exchange can be extended when multiple side-by-side plastic stents are placed.6 Stent occlusion not only causes cholangitis but also leads to patient discomfort and morbidity related to repetitive procedures. Bioabsorbable biliary stents and covered self-expandable metal prostheses have been described with promising results.7

Despite data showing efficacy of endoscopic therapy of ERCP for the treatment of biliary injuries based on physiologic mechanisms described, there are no randomized clinical trials to determine the best strategy. We suggest maximal reduction of intraductal biliary pressure inside the biliary ducts, using combined ES and stent placement. In selected cases endoscopic cyanoacrylate application could be considered (Box 41.1).

ERCP for Management of Biliary Adverse Events Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC)

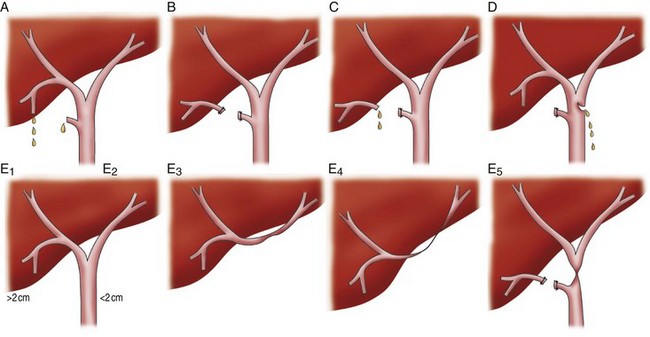

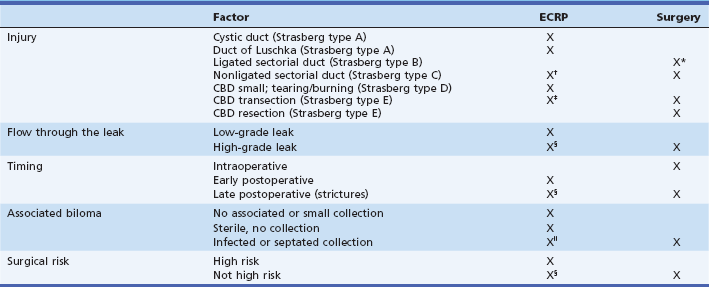

Strasberg classified iatrogenic biliary injuries according to anatomic considerations and type of treatment.8 We recommend using this classification, as it also allows lesions to be classified as being amenable to endoscopic management (Fig. 41.4).

The majority of biliary injuries are amenable to endoscopic management. These range from small tears and leaks to transections of the common bile duct (CBD).9

Nature and Magnitude of Biliary Injury

If there is continuity of the injured bile duct (Strasberg types A, C, and D), ERCP is considered the primary therapy. Endoscopic therapy is generally precluded for injuries with complete bile duct transection and presence of clips at the distal stump or lack of continuity between segments (Strasberg type E).10,11

CBD resection requires surgical management to reestablish ductal continuity. ERCP is helpful only to determine the type and extent of the injury while percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is complementary and allows determination of the proximal biliary anatomy.12 Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) can also be used to define biliary anatomy.

Complete CBD transection without resection nearly always requires surgical reconstruction. Even though some patients with complete transection of the CBD can be successfully treated endoscopically with or without the use of PTC,13 it is technically difficult and the long-term outcome of this approach is unknown.

Flow through the Leak

Clinically significant bile leak occurs in 0.1% to 0.5% of patients following open cholecystectomy, and initially was higher with LC. Because of a decrease in operator skill with open cholecystectomy, the injury rate may be increasing.14

The most common site of leakage is the cystic duct (78%), followed by peripheral right hepatic ducts of Luschka (13%) and other sites (9%), including the common hepatic duct, CBD, and T-tube tracts.15

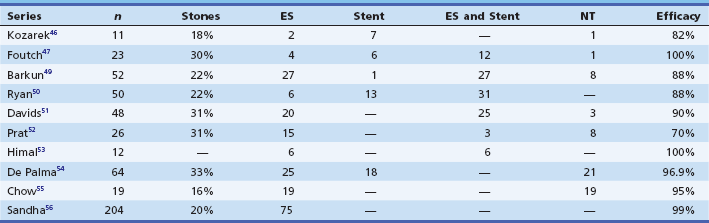

High output leaks were traditionally considered an indication for surgery. However, endoscopic therapy has become the main approach (Table 41.1). Shanda et al. defined a low-grade leak as a leak identified only after opacification of the intrahepatic biliary radicals with contrast and a high-grade leak as a leak observed fluoroscopically before intrahepatic opacification.15 Endoscopic therapy should be attempted even for high-grade leaks.

Time to Diagnosis

If the injury is identified intraoperatively, it is often repaired surgically.

Laparoscopically placed intraoperative biliary stents can be used to prevent stenosis at the choledochotomy and as an alternative method of closure of a choledochotomy.16

Treatment of Infected Biliary Collections and Related Infectious Adverse Events

Most collections and bilomas are treated with percutaneous catheter placement and administration of systemic antibiotics. If percutaneous drainage is inadequate, minimally invasive laparoscopic surgical techniques can be used. There are reports of endoscopic transmural drainage of bilomas.17

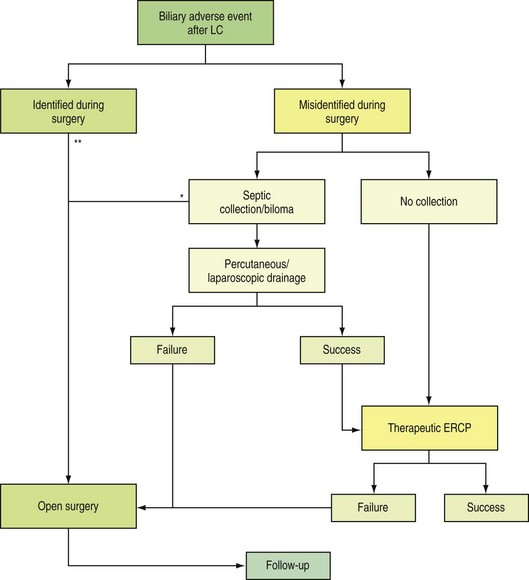

Surgical Risk

It is impossible to establish a rigorous evidence-based approach for patients with iatrogenic and postsurgical biliary injuries. We propose a guideline for the management of these patients (Table 41.2). In summary, most patients are candidates for therapeutic ERCP in the setting of a known or suspected biliary adverse event following LC. As shown in the proposed algorithm (Fig. 41.5), ERCP is a widely accepted therapy for high output fistulas and low-risk patients. Only types B and E lesions without continuity to the CBD and injuries identified intraoperatively leave ERCP as a secondary or adjuvant therapy to surgical repair (Box 41.2).

Table 41.2 Factors Influencing Endoscopic versus Surgical Treatment of Biliary Tree Injuries

CBD, Common bile duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

*Absent communication to CBD branches leads to late liver resection.

†Only if aberrant system communicates with CBD branches.

‡Stenting only if continuity can be established.

§ERCP seems as effective as surgery; other factors should be considered.

‖Drainage is priority; after drainage, endoscopic therapy should be used.

ERCP and Bile Leaks after Hepatic Resection

The incidence of bile leaks after hepatic resection is unknown. Many series report an incidence of approximately 11% but most minor bile leaks often seal with watchful waiting. Major bile leaks are often central in origin and occur as a consequence of failure to ensure the integrity of the bile ducts at the liver hilum (Fig. 41.6).

Coagulopathy is common in patients following hepatic resection. For this reason ES may be best avoided and stent placements without ES and injection of cyanoacrylate are alternatives. However, placement of large bore stents (≥10 Fr) without ES increases the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis as compared to large stent placement with ES.18 When glue and other sealants are used the duct must be selectively visualized by ERCP and the distal takeoff injected with approximately 1.5 mL of a cyanoacrylate compound (Histoacryl) (see Fig 41.3). Selective injection of glue is a well-recognized treatment approach that can be used as an adjuvant treatment to stent placement or as a primary treatment for large bile leaks (Video 41.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree