Chapter 32 ROLE OF NEEDLE SUSPENSIONS

Female urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are ubiquitous to the aging female population. A woman has an 11.1% lifetime risk of requiring a single surgery for POP, and one-third of those women will require a repeat procedure.1 A review of data from the National Hospital Discharge Summary in 1997 and 1998 concluded that 226,000 surgeries for POP2 and 135,000 for UI3 were performed, compared with 169,000 total knee replacements and 307,000 cholecystectomies. Twenty-one percent of patients undergo concomitant procedures for POP and UI.1,2 Both conditions have afflicted women for centuries, but during the past 50 years understanding of the pathophysiology and development of treatment options have progressed.

The bladder neck needle suspension was initially described by Pereyra in 19594 for treatment of urethral hypermobility; he initiated the concept of passing a ligature carrier through the retropubic space to transfer sutures placed to suspend or secure the anterior vaginal wall tissue. Today, the role of needle suspensions is decreasing; many practitioners are abandoning the procedure because of its reported low success rate and expansion of the use of the more “minimally invasive” sling procedures.5,6 One of the most significant advantages of modern-day needle suspensions is the ability to correct urethral hypermobility associated with a cystocele in patients with or without stress urinary incontinence (SUI) by providing support to the urethra, bladder neck, and bladder as a unit without the use of foreign materials.

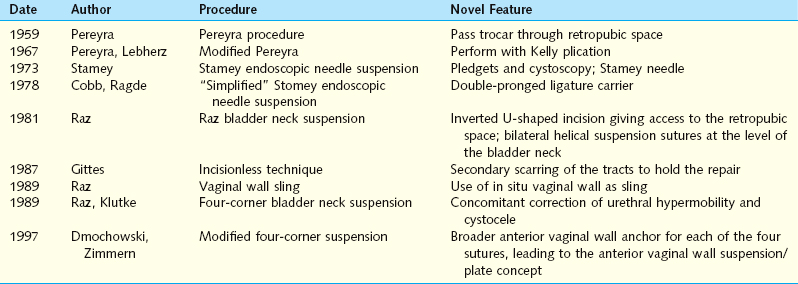

HISTORICAL REVIEW OF NEEDLE SUSPENSIONS (1949-1989)

Retropubic bladder neck suspensions were initially described in 1949 by Marshall, Marchetti, and Krantz7; the Burch procedure was described in 1961.8 The goal of these procedures was to fix the bladder neck into a high retropubic position, while returning the urethra to an abdominal position, thus allowing equal transmission of pressures to the bladder and bladder neck/proximal urethral regions. In 1959, Pereyra described “a simplified surgical procedure” to accomplish the same goal (support of the urethra and bladder neck) through a transvaginal approach with a resulting decrease in morbidity.4

Pereyra’s original procedure described the passage of a trocar needle via a small transverse suprapubic incision blindly through the retropubic space, lateral to the bladder neck, exiting through the anterior vaginal wall. The trocar was passed a total of four times, two times on each side. Pereyra used stainless steel wire; he recognized that the wires were apt to cut through the tissues but served as a temporary support mechanism until scarring and fibrous tissue developed to create a more permanent support. In 1967, Pereyra and Lebherz reported improved urinary continence results when the Pereyra procedure was combined with a Kelly plication.9 Together, the procedures corrected the anatomic defects that “neither procedure alone could remedy.” In his initial description, Pereyra emphasized the need to avoid tension on the sutures, recognizing already that it is scar formation that brings long-term support and good results.

In 1973, Stamey described the endoscopic vesical neck suspension.10 Similar conceptually to the Pereyra procedure, this technique recommended the use of cystoscopy to observe the needle passage near the bladder neck and introduced a series of specially designed needles for passage of the sutures. A Dacron pledget was used to buttress the periurethral tissues and decrease suture pull-through. The double-pronged ligature carrier was introduced in 1978 by Cobb and Ragde to decrease the number of passages and ensure a consistent fascial bridge.11

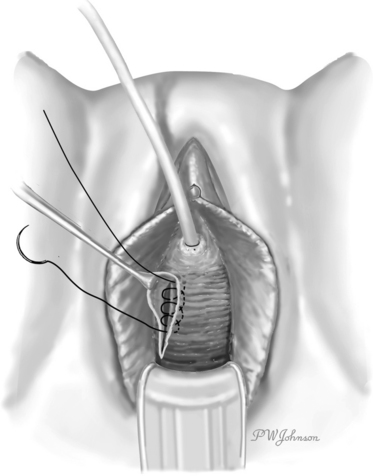

The Raz bladder neck suspension or modified Pereyra procedure was described in 1981.12 The key differences were using an inverted ∪-shaped incision vaginally, to allow dissection lateral to the urethra and bladder neck, entering the retropubic space to allow for adequate mobilization of the bladder and urethra, passing the ligature carrier under fingertip guidance to avoid bladder injury, and placing the anchoring sutures through the full-thickness vaginal wall (excluding epithelium) in addition to the pubocervical fascia (Fig. 32-1). The suspension sutures were secured more laterally in the vaginal wall to decrease the risk of damage or obstruction of the urethra.13 Because incontinence can occur after an isolated Kelly plication, Raz further modified the Raz bladder neck suspension to concomitantly correct a cystocele and to decrease postoperative incontinence, a procedure known as the “four-corner bladder neck suspension,” which is examined in detail later.

In 1987, Gittes and Loughlin proposed a no-incision technique that could be performed under local anesthesia in an outpatient setting.14 Because the sutures were placed through the full-thickness vaginal mucosa in a helical fashion at the bladder neck level and tied suprapubically under tension, it was believed that the sutures would pull through the vaginal mucosa and form an “autologous pledget” of scar tissue along their retracting path.

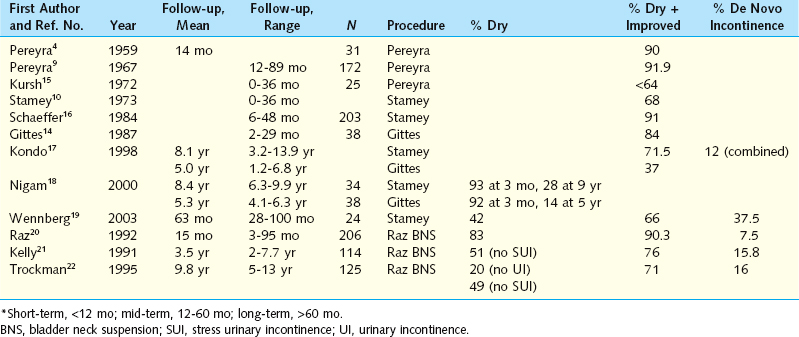

The short-term results of all these procedures were very promising, with success rates for subjective cure greater than 90%. As time passed and long-term data became available, it became apparent that it was difficult to reproduce the success of the initial surgeon (Table 32-1).

The morbidity of the needle suspensions was limited and included bleeding from the retropubic space and periurethral tissues; bladder injury, especially after a prior retropubic anti-incontinence procedure; suture entry into the bladder detected by cystoscopy; failure due to suture pull-through of the anchoring tissues; and rare reports of ilioinguinal nerve entrapment. Urinary retention and the development of de novo urge incontinence were very infrequent.23

Based on this overview of the various needle suspensions from 1959 to the late 1980s, it is clear that each new technique improved the preceding one by adding some important modifications that are still in use today (Table 32-2). Avoiding the periurethral tissue, fingertip guidance of the trocar through the retropubic space, and use of cystoscopy are some of the critical steps learned from several decades of vaginal needle suspension procedures.

CONTEMPORARY APPROACHES (1989-2005)

In 1997, the American Urological Association (AUA) Guideline Panel grouped all needle suspensions into one category. Compared to the Burch or the pubovaginal sling procedure, the results at 4 years were globally inferior, but the series were short and had very inhomogeneous methods of reporting and follow-up.24 More recently, the Cochrane database reviewed the role of needle suspensions for SUI and concluded that, although they were more likely to fail than open retropubic suspensions, the evidence was limited; no conclusions could be drawn when compared to the suburethral sling.25 Nonetheless, reports still emerge periodically on series from all over the world using the vaginal wall as the support mechanism. Therefore, we review in the following sections four procedures aimed at restoring the support of the anterior vaginal plate, either in its entirety (Four-Corner Bladder Neck Suspension and anterior vaginal wall suspension), beneath the urethra/bladder neck area (vaginal wall sling), or with support of the bladder neck and concomitant anterior colporrhaphy (goalpost technique); we then discuss several other series using similar or slightly modified techniques.

Four-Corner Bladder Neck Suspension (FCBNS)

The FCBNS,26 initially described by Raz in 1989, was a progression from the original Raz bladder neck suspension and attempted to correct a minimal to moderate cystocele and urethral hypermobility without performing a Kelly plication. Although the Kelly plication and/or anterior colporrhaphy was the standard treatment to repair cystoceles, there was a significant rate of postoperative SUI and cystocele recurrence. For the treatment of SUI, the Kelly plication had a cure rate of 63% to 92% at 1 year and 37% to 54% at 5 years of follow-up.27,28 Recent randomized studies have also revealed a success rate of 30% to 71% at 1 year for correction of prolapse stage I through IV with this ap-proach.29–31 The idea of combined correction of a cystocele and urethral hypermobility was a turning point in addressing the vaginal wall as a single unit and not as separate components.

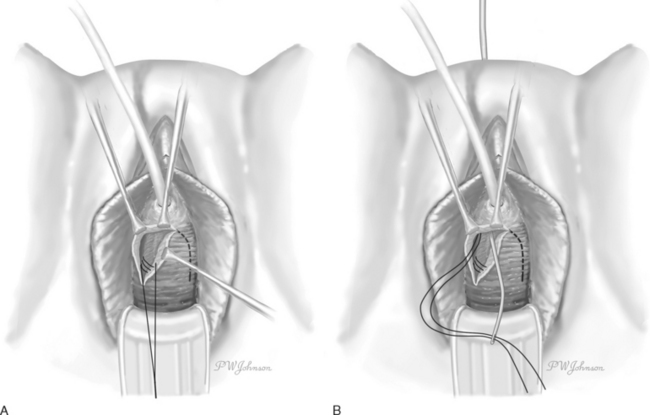

Briefly, the procedure involves creation of an inverted ∪-shaped anterior vaginal wall incision with the apex midway between the urethral meatus and the bladder neck.26 The pubocervical fascia is exposed, and the retropubic space is entered and developed laterally. Two pairs of helical nonabsorbable sutures are placed, one pair proximally incorporating the vaginal wall (excluding epithelium), the cardinal ligament, and pubocervical fascia; and the second pair located distally at the level of the bladder neck but avoiding the periurethral tissue (Fig. 32-2). The sutures are transferred suprapubically with a double-pronged Raz ligature carrier. Cystoscopy is performed to confirm no injury to the bladder or ureters and no suture entry. The sutures are then tied to themselves and to the corresponding sutures on the contralateral side, care being taken to avoid tension.

As for many other procedures, the long-term follow-up has not been as promising as the initial short-term reports. Suture pull-through has been a significant criticism. Kilicarslan and colleagues, with a follow-up of 3.8 years, reported a cure rate of 74%; cure was defined as absence of complaints and no evidence of leakage during urodynamic studies.32 With a mean of 37 months’ follow-up and using a standing cystography as an outcome measure, Dmochowski and associates reported a 53% success rate defined as no incontinence and an 83% success rate defined as 0 to 1 incontinent episodes per week.33 Recurrent cystocele was found in 57%, and 8/33 (24%) of women with their uterus in situ developed symptomatic uterine prolapse postoperatively. Constatini and coworkers reported a success rate of 85% with a mean of 62 months’ follow-up.34 However, in their study, patients underwent concomitant vaginal wall sling if the Valsalva leak point pressure (VLPP) was less than 60 cm H2O and the FCBNS was performed for correction of POP with or without incontinence. For correction of cystocele, 12 of 37 patients with grade 3 cystocele preoperatively failed based on physical examination postoperatively; de novo hysterocele was noted in 4 of 37 patients (10%).

Anterior Vaginal Wall Suspension

The ideal patient for the anterior vaginal wall suspension35 is a woman who experiences SUI due to urethral hypermobility and has a Baden-Walker grade 1 to 3 cystocele, but no midline defect on physical examination. Cystoceles can be graded not only clinicially but also radiographically. On a voiding cystourethrogram with lateral images, a grade 1 cystocele is defined as 0-2 cm of descent below the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis; grade 2 as 2 to 5 cm of descent; and grade 3 as > 5 cm of descent.36 In women with this lateral detachment, the anterior vaginal wall suspension reestablishes support and prevents the downward mobility of the anterior vaginal wall during straining efforts. This procedure is not intended to correct intrinsic sphincter deficiency. A unique aspect of the anterior vaginal wall suspension is its versatility to correct a cystocele at the time of a sling procedure or urethrolysis.

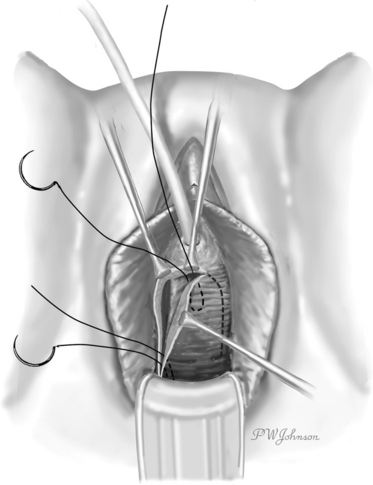

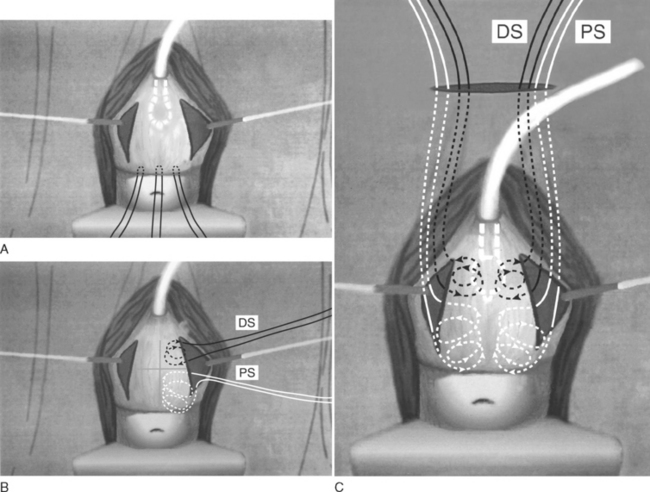

Conceptually, it is similar to the FCBNS in viewing the bladder, bladder neck, and urethra as a single unit, but the suspension sutures are placed not solely at “four corners” but over the entire length of the vaginal plate, from the bladder neck to the vaginal apex. It is believed that sutures placed broadly allow for greater distribution of pressure, thus decreasing the risk of suture pull-through (Fig. 32-3). This technical change was adopted after studies in a rabbit model done by Bruskewitz and colleagues demonstrated that the cross-sectional area serving as anchor determines the force required for tissue pull-through. These authors reported that suture loops cut through tissue at lower forces and act as a cutting string.37

A second important technical difference is the ability to excise redundant vaginal tissue laterally at the site of the primary defect. This maneuver narrows the potential space for lateral cystocele recurrence and recreates the natural lateral sulci present in the vagina. This technical modification resonates with the “pinch test” and “tuck procedure” described by Petros and Ulmsten.38,39

After the bladder neck is identified (balloon of Foley catheter) and marked with an ink pen, three marking sutures are placed at the vaginal apex: one in the midline, and then one approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the midline on each side (Figs. 32-4A and 32-5A). An incision is made from approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the bladder neck to the apical marking sutures. This incision is performed on both sides of the vagina, creating a trapezoid-shaped vaginal plate in the center with a width of approximately 3 cm and a length of 4 to 8 cm. A marking pen is used to divide this in situ vaginal wall plate into four equal quadrants (see Figs. 32-4B and Figs. 32-5B). A separate no. 1 polypropylene suture is used for each of the four suspension sutures, one suture in each quadrant. The suture is placed in a helical fashion, incorporating large segments of vaginal mucosa (minus epithelium) while remaining parallel to the vaginal plate (see Fig. 32-4B). At the proximal portion of the plate, the suture should incorporate the cardinal ligament at the time of hysterectomy or scar at the vaginal cuff.