Chapter 83 RECTOVAGINAL FISTULA

A rectovaginal fistula consists of an abnormal, epithelium-lined communication between the rectum and the vagina. It represents an extremely distressing problem for the patient and a surgical challenge for the physician. The reconstructive pelvic surgeon must have a full understanding of rectovaginal fistula to provide the patient with the most appropriate treatment option.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

It is important to consider the underlying cause of the rectovaginal fistula in preparing for a successful repair. The most common cause of rectovaginal fistula remains obstetric trauma,1,2 usually caused by an unrecognized injury with traumatic vaginal de-livery, wound infection, or an inadequate repair of a third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration. Up to 5% of vaginal deliveries result in these lacerations. Most heal when repaired at the time of labor. Prolonged labor and compression can result in ischemic necrosis of the vaginal septum, predisposing the delivering woman to development of a rectovaginal fistula. This is a greater concern in developing nations and likely not a large factor in industrialized countries such as the United States and Canada.

Rectal, cervical, uterine, and vaginal malignancy and radiation therapy are known causes of rectovaginal fistulas. The incidence of rectovaginal fistula after irradiation is 0.3% to 6%.3,4 The fistula may occur up to 2 years after irradiation because of progressive radiation damage. Any fistula associated with radiation therapy and malignancy must be biopsied to rule out recurrent malignancy before formal repair.

EVALUATION

Before formal repair, it is necessary to evaluate the patient for fecal incontinence. A review of 52 patients at the University of Minnesota revealed a 48% incidence of coexistent fecal incontinence.5 Among women who develop rectovaginal fistula after obstetric trauma, the incidence is probably much higher. It is essential to assess the function of the anal sphincter before surgical repair. Endoanal ultrasonography, anal manometry, and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency testing remain valuable tools to aid with the clinical evaluation. Ultrasound can easily identify defects in the internal anal sphincter. Defects in the external anal sphincter are more difficult to identify because of the hyperechoic pattern. Manometry can help quantify the resting and squeezing pressures of the sphincter muscle. Pudendal nerve testing helps identify underlying neuropathy.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Management of rectovaginal fistulas depends on several factors: cause, size, number, and location of the fistulas and the surgeon’s preference. Anal sphincter integrity and prior operations influence the choice of treatment. Regardless of the approach chosen, several principles require consideration before repair.

Excellent exposure allows good mobilization of tissue flaps. The fistulous tract should be exposed in its entirety and left intact. We tend to not excise the tract. This prevents iatrogenic enlargement of the fistula and allows us to use it in our repair. The rectal opening is closed in multiple, tension-free layers. Interposition of healthy tissue between the rectum and vagina should be used routinely. Common sources include labia fatty tissue (i.e., Martius flap), labial skin and underlying fatty tissue, gluteal skin, gracilis muscular flaps, and omentum. Case reports have described pudendal thigh fasciocutaneous island flaps and gluteal-fold flap repairs to aid in rectovaginal fistula repair.6,7 Several common techniques of tissue interposition can be found in Chapters 81 and 82. After closure of the fistula, anal sphincter defects should be addressed to restore normal sphincter function.

SURGICAL REPAIRS

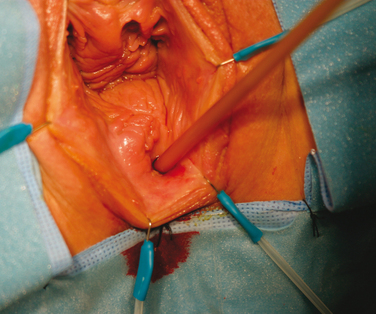

Complete bowel preparation is done, and antibiotics are given preoperatively. The patient is given general or spinal anesthesia and placed in the high lithotomy position. A Foley catheter is placed in the bladder. Use of a surgeon’s headlight and a ring retractor help to optimize exposure. A Foley catheter is inserted into the fistulous tract (Fig. 83-1). A circumferential incision is made around the Foley catheter, and the tract is dissected to the rectal wall (Fig. 83-2). A flap of distal vaginal is also prepared. The fistulous tract is then excised, leaving the rectal wall with an indwelling catheter (Fig. 83-3). The rectal wall is closed in two layers using 2-0 absorbable sutures (Fig. 83-4). The levator musculature is included in the closure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree