Chapter 80 RECONSTRUCTION OF THE ABSENT OR DAMAGED URETHRA

Damage to the female urethra requiring surgical intervention is rare. It is most commonly seen in underdeveloped countries where obstetric injuries predominate because of prolonged labor, particularly when there is maternal-fetal disproportion. It is postulated that the fetal head compresses the bladder neck and urethra against the undersurface of the pubis, causing pressure necrosis.1 With the advent of modern obstetric techniques, the most common causes of urethral injury are shearing injuries from scarring that occurs between the urethra and cervix in response to cerclage sutures, prior cesarean section, or other sources.

In industrialized countries, surgical trauma from antiincontinence surgery is the most common cause. Less common causes include damage from urethral diverticula, pressure necrosis from long-term indwelling catheters, pelvic fracture injury, and invasion from adjacent malignancies. Iatrogenic injuries may occur during urethral diverticulectomy, anti-incontinence surgery, anterior colporrhaphy, and vaginal hysterectomy. Erosions of synthetic slings and sutures from anti-incontinence surgery are seen with increasing frequency and may manifest years after the original surgery. This is fast becoming the most common reason for damage to the urethra, requiring various degrees of urethral reconstruction.2–6 The most likely cause is the increased use of synthetic materials and technical issues, such as dissecting too close to the urethra or tying the sling too tightly. In our experience, urethral diverticulectomy continues to be the most common cause of extensive urethral damage.7,8 This most likely results from failure to obtain a tension-free closure of the urethral defect that results from excision of the diverticulum. During bladder neck suspension, an inadvertent (and unrecognized) injury to the bladder or urethra may occur, or an errant suture may result in fistula formation or tissue necrosis. We have also seen several patients who sustained extensive tissue loss after a seemingly simple Kelly plication. It is postulated that the plication sutures were tied too tightly around a urethral catheter, resulting in pressure necrosis.

DIAGNOSIS

The next step in diagnosis is cystourethroscopy to evaluate the extent of the fistula and to assess the remainder of the urethra, particularly the length, viability, and sphincteric function of the proximal urethra. Visualization of the urethra is best accomplished with a 0- or 30-degree lens and a cystoscope with a 90-degree beak or flexible cystoscope. Cystourethroscopy is the modality of choice for diagnosing urethral erosions after sling placement.

MANAGEMENT

Indications for Surgery

When sphincteric incontinence is present preoperatively, we believe that it should be surgically corrected at the time of urethral reconstruction. We prefer to construct an autologous fascial pubovaginal sling9,10 with an interposed labial fat pad flap7,9,11,12 between the sling and the reconstructed vesical neck. Others have recommended transvaginal bladder neck suspension,13 but in our experience, this has a failure rate of about 50%.9 Although it is tempting to use a synthetic sling, we do not recommend it because of the possibility of infection or erosion. It may be prudent to use allograft or xenograft tissue for the sling, but because of lack of long-term follow-up and some early failures, we have chosen these kinds of tissue grafts very selectively.4,8

There are three general approaches to urethral reconstruction: anterior bladder flaps,13,14 posterior bladder flaps,15 and vaginal wall flaps.1,7,12,16–18 These techniques appear to be comparable with respect to creation of a neo-urethra. However, when the vesical neck and proximal urethra are involved, which is usually the case, postoperative incontinence rates of about 50% are to be expected unless a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure is performed.13–15 We believe that vaginal reconstruction is considerably easier and faster, is much more amenable to concomitant anti-incontinence surgery, and is associated with much less morbidity than the bladder flap operations.

Principles of Surgical Technique

In women with damaged urethras, the vaginal tissue is often scarred, fibrotic, and ischemic. Before surgery, careful examination of the vagina is necessary to determine the actual extent of urethral tissue loss and to assess the availability of local tissue for use in the reconstruction. In most instances, there is sufficient tissue in the anterior or lateral vaginal wall that can be mobilized and used for the reconstruction.1,7,9,12,13,16–18 Occasionally, it may be necessary to use an adjacent labial16,19 or thigh flap.20,21 Alternatively, an anterior bladder flap can be used.13

In patients undergoing urethral reconstruction for urethral erosion after synthetic sling placement, attempts should be made to remove all synthetic material, including nonabsorbable mesh and sutures.2 When infection is absent, bone anchors can be left in place because of the difficulty in retrieving them. However, if infection exists, it is advisable and usually straightforward to identify and remove bone anchors. The urethra usually can then be reconstructed primarily.

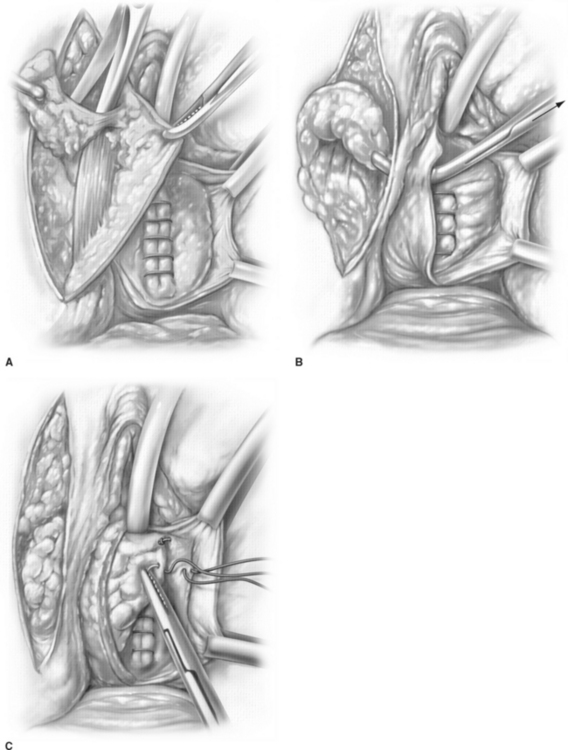

After reconstruction of the urethra, it is often advisable to interpose a well-vascularized pedicle flap over the site of the repair. Sources include labial,9,13,22 rectus abdominal,17,23 gracilis,7 and thigh tissue.20,21 In most patients, nothing more than a labial fat pad graft is necessary (Fig. 80-1).

(Modified from Mattingly RF, Thompson JD: Ch. 27. In Mattingly RF, Thompson JD [eds]: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology, 6th ed. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1985, p 665.)