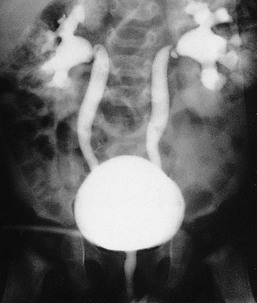

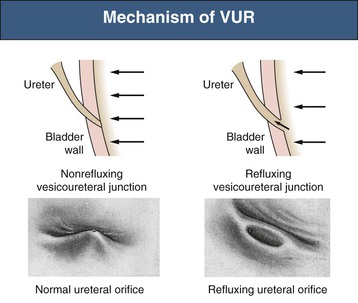

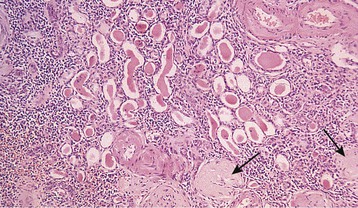

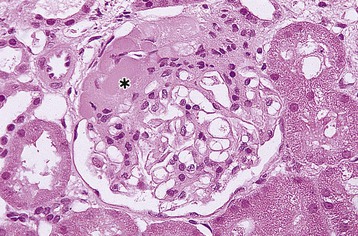

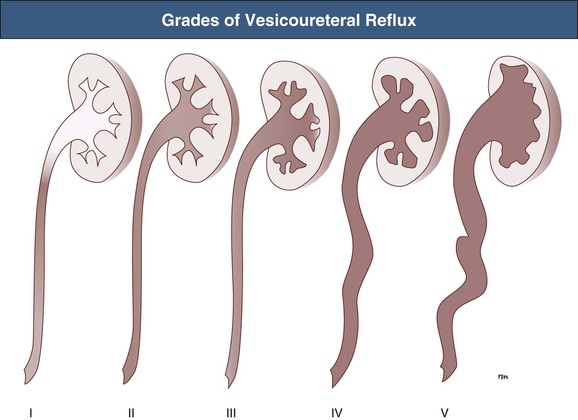

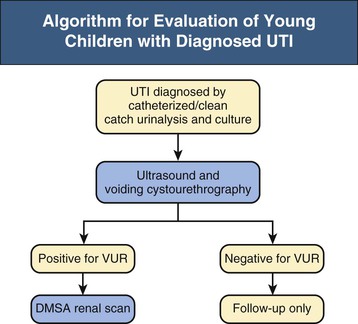

Ranjiv Mathews, Tej K. Mattoo Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a congenital or acquired abnormality in which there is retrograde flow of urine from the bladder to the kidneys. This retrograde flow of urine, although normal in some animals, is not normal in humans. VUR may be primary (congenital) and associated with or without associated syndromes, or secondary, such as from increased bladder pressure resulting from obstructive uropathy or neurogenic bladder. Vesicoureteral reflux may be suggested by fetal ultrasound in pregnancy (in which renal pelvis dilation is observed) or after urinary tract infection (UTI) in childhood. The presence of VUR increases the risk of upper tract UTI, and the two together can cause renal injury leading to scarring of the kidney termed reflux nephropathy (RN). RN may present as hypertension, toxemia of pregnancy, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and even end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Whereas RN involves primary injury to the renal parenchyma, some patients also have proteinuria as a result of secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Traditional management includes prompt treatment of UTI and long-term antimicrobial prophylaxis until the resolution of VUR. Surgical correction of the VUR may be recommended in those with high-grade VUR who have recurrent UTI in spite of antimicrobial prophylaxis or who are noncompliant with medical management. Debate persists on the superiority of one intervention over the other; most studies have concluded that long-term outcomes are similar. Vesicoureteral reflux is classified by radiologic evaluation on voiding cystourethrography (VCU) into five grades as defined by the International Reflux Study in Children (Fig. 63-1 and Table 63-1).1 Grade I is reflux into the ureter; grade II is reflux into the renal pelvis without any dilation of the calyces; grade III is reflux to the renal pelvis with mild dilation of the renal pelvis; grade IV is reflux to the renal pelvis with greater dilation of the renal pelvis; and grade V is reflux to the renal pelvis with ureteral and pelvic dilation. An example of grade V reflux is shown in Figure 63-2. Table 63-1 Classification of VUR. The International Reflux Study in Children classification. Grading of VUR is used to predict the outcomes of children with VUR. Because VUR may resolve spontaneously, grading is used to standardize management strategies as well as to compare clinical outcomes between institutions. Although it is widely used, the classification system is not perfect; differences between grade III and grade IV are not always obvious. The degree of reflux may be modified by how aggressively the bladder is filled during VCU. Ureteral dilation may also be present without calyceal dilation, leading to difficulties with grading. Vesicoureteral reflux is often first suggested by dilation of the fetal kidney during ultrasound examination. VUR is suspected when the fetal renal pelvis is more than 5 mm in anteroposterior diameter; a diameter of more than 10 mm is considered to be high-grade VUR. In neonates who had evidence of fetal dilation, as many as 13% to 22% will have VUR on VCU. Indeed, it is estimated that 1% to 2% of healthy children have VUR, with a higher frequency in boys and premature infants.2 The incidence of renal dysplasia is also greater in male infants with VUR.3 Most cases of grades I to III VUR will spontaneously resolve within the patient’s first year of life, whereas grades IV and V are more likely to persist. Spontaneous resolution of VUR is greater in male infants. Vesicoureteral reflux is also diagnosed in 30% to 40% of children presenting with UTI, predominantly girls. VUR is both less common and less severe in African American children.4,5 Only about one third as many African American as Caucasian girls with UTI have VUR, and no significant differences in age or mode of presentation exist between the two races. Renal scarring is responsible for 5% to 10% of ESRD in pediatric and adult patients.6,7 In the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) study, in children with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 to 90 ml/min/1.73 m2, RN was the underlying cause for CKD in 14.8% of the patients. Primary VUR is a congenital anomaly of the ureterovesical junction caused by a preexisting anatomic abnormality with shortening of the intravesical submucosal length of the ureter, leading to an incompetent valve (Fig. 63-3). The formation of the ureteral bud from the mesonephric duct signals the initial development of the metanephric kidney, the final stage of renal development. The ureteral bud interacts with the mesenchyme to give rise to the metanephric kidney. As the mesonephric duct is gradually absorbed into the enlarging urogenital sinus (the precursor of the developing bladder), the location of the ureteral bud plays a role in the eventual location of the ureteral meatus within the bladder. If the ureteral bud reaches the urogenital sinus too early because of the absorption pattern of the mesonephric duct, it is eventually located more laterally and proximally in the bladder. This location is associated with the development of reflux because there is reduction in the intravesical submucosal length of the ureter. The ureterovesical junction is designed to prevent free reflux of urine from the bladder to the kidney. The ureters pass into the bladder through the detrusor in an oblique path. The distal end of the ureter is located submucosally within the bladder. The length of the submucosal ureter is critical in the prevention of VUR. The muscles of the ureter extend into the trigone of the bladder and mesh with the fibers from the opposite ureter. This intermingling of fibers helps anchor the ureters into the trigone of the bladder. The distal submucosal segment is compressed against the muscular bladder wall with bladder filling, acting as an additional mechanism to prevent reflux. Because urine is propelled antegrade down the ureter, the tone of the ureter and the meatus in the bladder also help prevent reflux. Multiple genes are involved in the development of VUR. PAX2 (necessary for ureteral budding in mice), glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), angiotensin II type 2 receptor, and uroplakin 3 (which is a component of tight junctions in uroepithelial cells) have been implicated in the development of VUR in mice; however, their role in human VUR remains controversial.8,9 Neither autonomic innervation nor histology of the ureterovesical junction is different between patients with VUR and controls.10 Reflux nephropathy is thought to result from one of two processes (Table 63-2).51 Prenatal renal injury has been postulated to be secondary to the “water-hammer” effect of high-grade reflux and occurs in the absence of infection. This typically causes renal dysplasia. This form of renal scarring, which is also called congenital RN, is more commonly noted in infants with high-grade VUR, and there is a greater predominance of males in this cohort. The second mechanism for development of renal injury is the combination of VUR and repeated UTI, which is also called acquired RN. In these children, who are more commonly female, the combination of upper tract infection and reflux leads to renal inflammation and permanent scarring. Table 63-2 Types of renal damage associated with VUR. * Depends on unilateral versus bilateral involvement, and the severity of renal involvement. (Adapted from reference 51, with permission.) In both conditions, the damage to the kidney is likely to be greatest in children younger than 2 years, particularly in those with severe VUR.11 Renal injury is more common in this age group because of delay in diagnosis of UTI as a result of the nonspecific clinical presentation, the difficulties in obtaining urine specimens, and the higher prevalence and severity of VUR in infants. Reflux nephropathy is diagnosed by using technetium Tc 99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) renal scanning as defects in the renal outline.12 These defects can be seen in the absence of febrile UTIs. As noted previously, high-grade prenatal reflux can lead to renal injury in the absence of infection. Unfortunately, renal scarring secondary to UTI is indistinguishable by DMSA renal scan from that caused by prenatal renal dysplasia. In addition, renal injury can be noted after febrile UTI in the absence of identified VUR. Finally, renal scarring as shown by technetium Tc 99m DMSA scan correlates more closely with the severity of VUR than with a history of UTI.13 The process of renal scarring may take several years; in one study, the mean time from discovery of VUR to the appearance of a renal scar was 6.1 years.14 Grossly, the injury favors the renal poles and is associated with clubbed calyces with medullary and cortical damage. The injury results from the local inflammatory response that may persist with chronic inflammation, tubular injury, local fibroblast activation, and interstitial collagen deposition (Fig. 63-4).15 The loss of nephrons is associated with hyperfiltration and hypertension that result in proteinuria and progressive loss of renal function. This can also lead to the development of FSGS (Fig. 63-5). Patients with primary VUR may present in a variety of ways (Box 63-1). The three most common presentations are during follow-up for antenatal hydronephrosis, after a diagnosis of UTI, and on screening of a sibling of a patient with VUR. Diagnosis of VUR may be suspected in utero with unilateral or bilateral hydronephrosis and confirmed at birth with VCU. There is a higher incidence of male infants diagnosed with VUR after identification of antenatal hydronephrosis.16 Spontaneous resolution of the VUR occurs more commonly in boys with lower grades and unilateral reflux; infection rates are also lower in this cohort.17 Female infants are more likely to have lower grades of VUR and are also less likely to develop renal damage compared with newborn boys. Reflux in newborn boys may be a result of elevated bladder pressures secondary to dyssynergia of the urethral sphincter, which improves with time with secondary resolution of even higher grades of VUR.18,19 Vesicoureteral reflux is most commonly found after UTI, particularly in a young child. The prevalence of VUR is higher in younger patients and decreases with age (Table 63-3). In neonates and toddlers, UTI may be manifested as failure to thrive as opposed to typical symptoms of dysuria and frequency. VUR is more common in patients with complicated or upper tract UTI. Because VUR may potentiate the effect of UTI in children, the recommendations for evaluation of UTI have included ultrasound and VCU after resolution of the first UTI in both boys and girls (Fig. 63-6). However, in its most recent recommendations, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) from the United Kingdom and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not support routine voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) in all children and children 2 to 24 months old, respectively, with first febrile UTI.20 Table 63-3 Prevalence of VUR in patients with urinary tract infection, according to age. (From reference 25.) Most children diagnosed with VUR after a UTI are younger than 7 years. UTI in these patients may be associated with modifiable host factors, such as voiding dysfunction and constipation. For example, toilet-trained children with VUR identified after a UTI have a 43% incidence of dysfunctional voiding.21 Approximately one third of siblings of an index patient with VUR also have VUR.22 There is a slightly higher incidence of VUR in female siblings of female index patients; 75% of children with VUR identified by sibling screening are asymptomatic. The incidence of renal damage is also lower in the siblings diagnosed with reflux compared with the index patient with VUR.23 For example, UTI with progression of scar was noted in only 5% of siblings with VUR observed for 3 to 7 years, and most of those with grades I and II VUR had resolution.23

Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux and Reflux Nephropathy

Definition

Classification

International Reflux Study in Children Classification of Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

Grade

Degree of VUR

I

Ureter only

II

Reflux into ureter, pelvis, and calyces with no dilation and with normal calyceal fornices

III

Mild or moderate dilation and/or tortuosity of the ureter and mild or moderate dilation of the pelvis; no or slight blunting of the fornices

IV

Moderate dilation and/or tortuosity of the ureter, and moderate dilation of the pelvis and calyces; complete obliteration of the pelvis and calyces; complete obliteration of the sharp angles of the fornices but maintenance of the papillary impressions in the majority of the calyces (see Fig. 63-7C)

V

Gross dilation and tortuosity of the ureter, pelvis, and calyces; the papillary impressions are no longer visible in the majority of calyces (see Fig. 63-2)

Epidemiology

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Reflux Nephropathy

Types of Renal Damage Associated with Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

Congenital

Acquired

Time of occurrence

Often prenatal

Postnatal, sometimes in adulthood

Previous urinary infection

Not usually

Usually

Gender

Usually boys

Usually girls (particularly after infancy)

Grade of VUR

Usually grades IV and V

Grades IV and V less common

Renal scarring

Often present

Present in minority of cases*

Associated bladder dysfunction

Hypercontractile bladder common

Less commonly, high-capacity bladder with incomplete voiding

Pathology

Clinical Manifestations

Presentation with Vesicoureteral Reflux

Reflux Identified Secondary to Antenatal Hydronephrosis

Reflux Identified After a Urinary Tract Infection

Prevalence of Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR) in Patients with Urinary Tract Infection, According to Age

Age

Percentage with VUR

2-3 days

57

3-6 days

51

2-6 months

60

7-12 months

35

1-4 years

50

5-9 years

35

10-14 years

14

14 years

10

Adult

5

Sibling Vesicoureteral Reflux

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux and Reflux Nephropathy

Chapter 63