Chapter 74 POSTERIOR WALL PROLAPSE: SEGMENTAL DEFECT REPAIR

Pelvic organ prolapse is common in women. The lifetime risk for undergoing an operation for prolapse or urinary incontinence is estimated to be 11.1%.1 The posterior wall of the vagina primarily provides support over the anterior rectum and posterior cul-de-sac. Prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall may result from the presence of an enterocele, sigmoidocele, rectocele, or a combination of these entities. This chapter focuses on the herniation of the anterior rectum into the posterior vaginal wall as the cause of the prolapse. A variety of surgical procedures are available for the management of posterior vaginal wall prolapse, including posterior colporrhaphy, site-specific defect repair, posterior fascial replacement, transanal or transperineal repair, and a sacral colpoperineopexy Posterior colporrhaphy and site-specific defect repair for surgical repair of posterior wall prolapse are discussed.

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

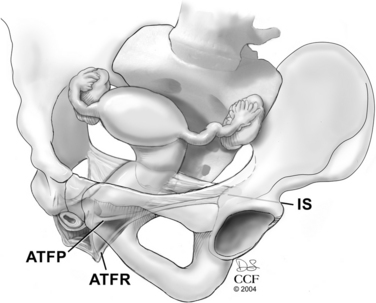

The connective tissue supports of the posterior vaginal wall are in continuity from the apical support of the vaginal vault (originating at the sacrum) to the perineal body. The apical portion of the anterior and posterior vaginal wall is provided by the suspensory support of the cardinal-uterosacral ligaments. The cardinal-uterosacral ligaments provide a mesentery of support directed toward the sacrum (S2 to S4) and pelvic side wall. The broad posterior fan of support directs the proximal (apical) portion of the vaginal axis posteriorly, and the contracted levator ani muscles direct the midportion of the vagina and rectum anteriorly toward the pubic symphysis. This orients the proximal vagina and rectum in a horizontal plane, supported over the pelvic floor muscles rather than a vertical orientation through the levator hiatus.2 The connective tissue attachments of the midsection of the posterior vaginal wall are directed laterally and cranially to the levator ani muscular side wall.3 The proximal halves of the posterior and anterior vaginal wall are attached to the same condensation of endopelvic fascia on the levator ani muscles, the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis. The distal half of the posterior vaginal wall has a separate, caudal attachment to the pelvic side wall, the arcus tendineus fasciae rectovaginalis.4 These separate lines of attachment of the anterior and posterior vaginal wall give the distal portion of the vagina an H shape (Fig. 74-1).

The perineal body is the central connection between the two sides of the perineal membrane, which originates bilaterally on the medial portion of the ischiopubic rami. Within the perineal body lie the bulbocavernosus muscle, superficial transverse perinei muscle, and the external anal sphincter and the rectovaginal septum, or Denonvilliers’ fascia. Extending from the posterior cul-de-sac to the perineal body, the rectovaginal septum is the fused, endopelvic fascial remnant of the embryonic posterior cul-de-sac.5,6 The role of the perineal body is to resist caudally directed force provided by the rectum and provide a physical barrier between the vagina and rectum. The perineal body’s mobility is limited by an intact connective tissue support within the vagina from the sacrum to the perineal body and an intact perineal membrane from ischiopubic ramus to ischiopubic ramus.3

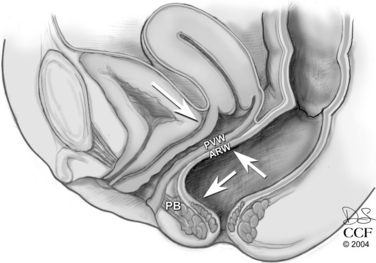

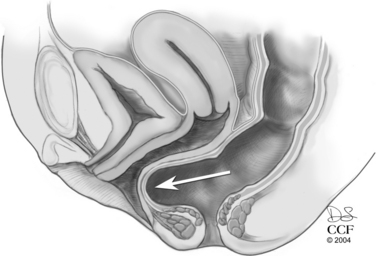

An increase in intra-abdominal pressure, such as a Valsalva maneuver, flattens the horizontally oriented upper vagina against the rectum and pelvic floor musculature. In the distal vagina, a Valsalva maneuver causes an equal increase in pressure against the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. No net strain is placed on the connective tissue support of the vaginal wall (Fig. 74-2). However, if the levator hiatus is widened or not closed, two things may happen. First, the vagina may lose the horizontal orientation of its axis. As the vagina becomes more vertically oriented, intra-abdominal pressure pushes the pelvic organs through the levator hiatus and toward the genital hiatus. The anterior and posterior vaginal walls then do not lie in apposition. An increase in intra-abdominal or intrarectal pressure, such as that obtained with straining for a bowel movement, is not met with an equal measure of pressure of the anterior vaginal wall. Instead, the posterior vaginal wall pressure meets the atmospheric pressure present in the open vagina (Fig. 74-3). In both situations, an increase in abdominal pressure places a net force on the connective tissue supports of the posterior vaginal wall. This force on the connective tissue supports may attenuate or break the posterior vaginal wall, or it may uncover damage done by a prior event, such as childbirth.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Many women with posterior wall prolapse are asymptomatic. Women who have prolapse that protrudes beyond the hymenal ring are more likely to be symptomatic.7 This bulge may be associated with vaginal pressure or pain, which worsens as the day progresses or with abdominal straining. This bulge may affect urinary, sexual, and defecatory functions.

As the posterior vaginal wall balloons upward toward the anterior vaginal wall and outward toward the genital hiatus or beyond, urinary function may be altered. Inside the vagina, the distended posterior vaginal wall may provide additional support of the urethra and mask or decrease the severity of urinary incontinence. Urodynamic investigations, with and without reduction of the posterior wall prolapse, have demonstrated that when the posterior wall prolapse is retracted, there are significant decreases in the maximum urethral closure pressure and functional urethral length and an increase in leak volumes.8 Beyond the genital hiatus, posterior wall prolapse may partially obstruct the external urethral meatus, altering the stream of urine.

Sexual function is a complicated issue involving both partners’ psychological and physical well-being. Prolapse protruding beyond the genital hiatus may lead to an altered body image and self-esteem. This may be worsened by fear of urinary or anal incontinence. Prolapse may be significant enough to require reduction before even attempting to have vaginal intercourse. A widened genital hiatus may decrease sensation for both partners during intercourse. The woman’s partner may also be concerned about causing pain or discomfort or about contributing to worsening of the prolapse.

Defecatory dysfunction and pelvic organ prolapse often coexist in women. A ballooning of the anterior rectum into the posterior vaginal wall or perineal body may alter the process of defecation. Stool may be trapped in the distended rectal pouch, leading to incomplete rectal emptying. Women may employ digitally placed pressure in the vagina, on the perineal body, or within the rectum to evacuate the stool. Some woman may perceive this as constipation (i.e., straining to have a bowel movement or an unproductive urge to defecate). However, constipation is often unrelated to a rectocele, such as that related to irritable bowel syndrome, slow-transit colon, or secondary constipation related to medications or neurologic disorders. Determining if the woman’s defecatory dysfunction is related to her posterior prolapse may be difficult to discern. Weber and colleagues9 examined bowel function and severity of posterior wall prolapse and found no correlation. If a woman’s sole defecatory complaint is incomplete rectal emptying that resolves with vaginal splinting, she is likely to have functional improvement after surgical correction.

A thorough history, including direct questions about fecal incontinence, should be obtained. Fecal incontinence may also coexist with posterior vaginal wall prolapse. There is an association with a rectocele, which protrudes beyond the hymen and anal incontinence.10 A descending perineum may provide stretch on the pudendal nerve, which innervates the external anal sphincter. This stretch injury may lead to denervation of the external anal sphincter and fecal incontinence. Prior obstetric trauma that injures the external anal sphincter may also result in fecal incontinence.

The goal of the physical examination is to recreate the woman’s symptoms. A validated measure of pelvic organ prolapse is the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree