Chapter 75 POSTERIOR REPAIR USING CADAVERIC FASCIA

Traditional posterior colporrhaphy for symptomatic rectoceles has been associated with failure rates as high as 35% and de novo dyspareunia rates ranging from 6% to 41%.1 The technique involves midline plication of the levator muscles and rectovaginal fascia to obliterate the fascial defect and perineorrhaphy to reapproximate the central tendon and perineal body.2 Inherent problems exist with traditional posterior repair. First, the success of the repair relies on the patient’s own tissue, which has already shown a propensity for weakness. Second, by attempting to obliterate the fascial defects, the patient’s anatomy is inevitably distorted, and the procedure can result in vaginal narrowing and dyspareunia. The patient may complain of constriction of the vaginal tube or may feel a ridge in the midline of the posterior wall due to suture placement.

The use of defect-specific rectocele repair is an attempt to alleviate the vaginal narrowing and dyspareunia associated with traditional repair. The technique involves identification of fascial tears and plicating nearby durable fascia over the defect. Recurrence rates of 18% to 23% with mean follow-up periods of 12 to18 months have been reported along with variable improvements in bowel habits.3–5 As with traditional colporrhaphy, the repair relies on the patient’s inherently weak tissues to repair fascial defects. By failing to address the entire posterior vaginal wall, all areas of fascial weakness may not be identified, increasing the likelihood of failure.

CADAVERIC FASCIA

The choice of fascia for rectocele repair with cadaveric fascia is of utmost importance in determining surgical outcome. Fascia lata is strong, regardless of a patient’s age or medical condition, and it has three to four times more tensile strength than rectus fascia.6 Our choice of fascia is Tutoplast (Mentor Corp., Santa Barbara, CA). Tutoplast is prepared by a five-step process that involves screening of donors, cleansing, denaturization of antigens and viruses, solvent dehydration, and gamma irradiation. The tensile strength and tissue stiffness of nonfrozen cadaveric fascia lata has been investigated, and it is comparable to that of autologous fascia lata.7 Studies have compared solventdehydrated and freeze-dried cadaveric fascia lata, another commercially available preparation. Solvent-dehydrated fascia lata has significantly greater stiffness, maximum load to failure, and maximum load per unit of graft compared with freeze-dried fascia lata.8

All commercially available cadaveric fascia lata is not the same. The method used to prepare the tissue ultimately affects its tensile strength and subsequent surgical outcomes. We prefer the use nonfrozen cadaveric fascia to commercially available synthetic mesh material, which carries inherent risks of erosion and infection. Milani and colleagues9 described 31 women who underwent posterior repair with Prolene mesh who had an erosion rate of 6.5%. Other studies have reported similar findings, with erosion rates as high as 48%.10

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

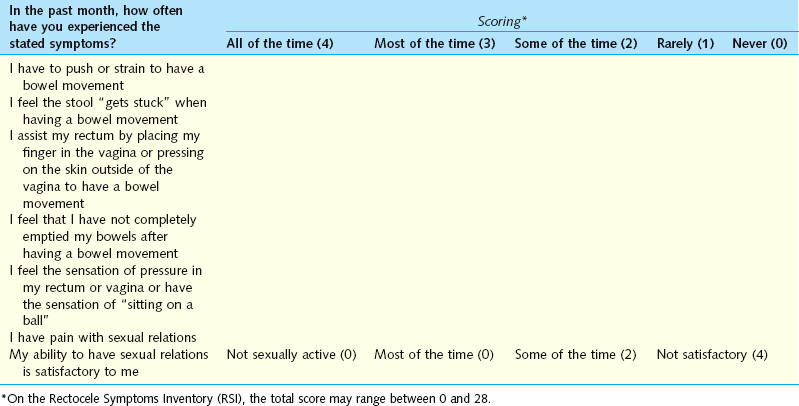

Before undergoing rectocele repair, a thorough history is obtained focusing on the symptoms associated with posterior prolapse. Based on the results of a series of questions in the Rectocele Symptom Inventory (Table 75-1), patients are assigned a preoperative score that correlates with the degree of symptoms. Questions focus on three areas of symptoms bowel function with symptoms that include straining, stool trapping, the need to manually reduce the rectocele to facilitate defecation, or a feeling of incomplete emptying after defecation; prolapse symptoms, which include vaginal pressure or the feeling of sitting on a ball; and sexual function, which includes dyspareunia and overall sexual satisfaction. We do not routinely repair rectoceles that are asymptomatic or low grade because the theoretical risks of surgery or its side effects outweigh the benefit gained. For patients who present with constipation or bowel dysfunction that does not correlate with the severity of posterior prolapse, referral to a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon may be beneficial before considering surgical repair.

Physical Examination

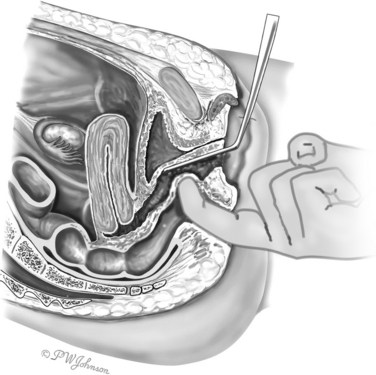

A systematic examination of the anterior, apical, and posterior compartments is performed with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. The posterior blade of a Graves speculum is used to displace the anterior vaginal wall and examine the posterior wall at rest and with straining. A simultaneous rectal examination using the index finger is performed to push the posterior vaginal wall forward (Fig. 75-1). Finger examination allows simultaneous assessment of the integrity of the rectovaginal fascia and the integrity of the external anal sphincter. Sphincter evaluation is especially important in patients who complain of fecal incontinence, and it can rule out other causes of defecatory dysfunction (e.g., rectal prolapse or intussusception, large hemorrhoids, skin tags). The perineal body should be evaluated for associated defects. Patients who present with a widened vaginal introitus or a shortened perineum, signified by a decreased distance between the posterior margin of the vagina and the anterior margin of the anus, may benefit from a simultaneous perineal repair.

We use the Baden-Walker system to classify rectoceles preoperatively (Table 75-2). In most cases, grade 1 rectoceles are incidental findings and asymptomatic. Only patients with grade 2 to grade 4 rectoceles and associated symptoms of stool trapping or the need to splint the vagina or perineum to facilitate defecation are considered candidates for surgical repair.

Table 75-2 Baden-Walker Rectocele Classification

| Anatomic Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Posterior wall protrusion toward introitus with strain |

| Grade 2 | Posterior wall protrusion to the introitus with strain |

| Grade 3 | Posterior wall protrusion outside of the introitus with strain |

| Grade 4 | Posterior wall protrusion outside of the introitus at rest |