Chapter 43 PERCUTANEOUS VAGINAL TAPE SLING PROCEDURE

The classification of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) has evolved from fundamental anatomic findings to a more physiologic description of urinary leakage secondary to increases in abdominal pressure. Although considered by some as controversial, intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) often coexists in the setting of urethral hypermobility. Conventional management has largely been with bladder neck sling placement. Recent changes to the etiologies of SUI have led to changes in these beliefs.1 Currently, it appears that the degree of ISD and the degree of anatomic displacement of urethral support determine the fundamental basis for selection of surgical treatment options.

There exists a strong interest in maintaining a simple, effective, and minimally invasive approach to the management of SUI that may, in fact, address almost all types of incontinence. To this end, the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT; Gynecare, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ) was devised in the mid 1990s as an alternative to other synthetic and biological mesh placements suburethrally. Data that are now becoming available reveal that success (depending on how measured) is quite good and durable.2–4 Accordingly, the advent of the TVT procedure and its accordant success has yielded the development of the percutaneous vaginal tape (PVT), which allows placement of a synthetic polypropylene mesh tape suburethrally in an antegrade fashion.5 The technique is similar to TVT in that it places a synthetic sling below the mid-urethra in a tension-free fashion, but it uses the widely available generic polypropylene mesh and Stamey needle passers for antegrade passage. The mesh itself can be tailored to size, offering the surgeon flexibility in the management of more severe types of incontinence or complex situations or anatomy.

PATIENT SELECTION

When the procedure for TVT was introduced, all female patients with SUI who had maximized their nonsurgical treatment were considered candidates for this procedure.2,3 As with all anti-incontinence procedures, relative contraindications included an active urinary tract infection and anticoagulation therapy. Although no procedure is 100% effective, recent studies on the outcomes of patients undergoing the TVT procedure provide an opportunity to make some basic selection criteria for ensuring a high rate of successful outcomes.2–4 As described in the following paragraphs, there may be potential patient selection limitations for midurethral slings that are not inherent in the traditional pubovaginal sling placed at the proximal urethra and bladder neck.

In general, moderate to severe obesity is not a contraindication; obese patients appear to have minimal operative and postoperative complications with the TVT procedure.6 Successful outcomes are achieved when the TVT procedure is performed in patients undergoing concomitant pelvic organ prolapse repairs. Major complications of vascular injury and bowel injury leading to death are unique to the TVT procedure as secondary consequences of blindly passing large trocars in a retrograde, retropubic fashion. Although major vascular bleeding and possibly bowel injuries have been rarely reported with other anti-incontinence procedures, the inability to reliably prevent these complications from occurring at all has been the major reason for surgeons’ opting to place the midurethral sling using small, percutaneous ligature carriers in an antegrade, retropubic fashion.5,7 By this method, the ligature carrier can be safely guided along the posterior aspect of the symphysis pubis, thereby decreasing risks for vascular or bowel injury.

Because the sling material for PVT and TVT are placed at the mid-urethra, continence is provided by midurethral kinking or “knee kinking” of the urethra during active movement of the urethra with Valsalva or stress maneuvers. This has several important implications in regard to patient selection. First, although several reports have shown that correction of the hypermobile proximal urethra and bladder neck demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Q-tip testing is not required for a successful outcome, successful outcome appears to be dependent on a hypermobile urethra that induces ISD.8 The midurethral placement of the sling is at the fulcrum of the mobile urethra and does not affect displacement of the urethra and bladder neck as defined by Q-tip testing. However, for the sling to provide a continence mechanism, the urethra must be actively “bent” over the midurethral sling, in order to prevent urinary leakage during stress maneuvers. Therefore, patients with a mobile urethra demonstrating significant hypermobility (>30 degrees) with SUI in the absence of a bladder contraction would seemingly have the highest probability for a successful outcome.

Alternatively, patients with severe ISD at rest with or without hypermobility are more likely to have less favorable outcomes. Severe ISD is indicative of an open bladder neck at rest and is not affected by a midurethral sling that is placed tension-free without causing an increase in urethral resistance at rest. Even in cases of severe ISD and a hypermobile urethra, leakage may occur with an open bladder neck before any urethral movement begins to provide coaptation by “kinking” of the midurethral sling. No prospective reports have been published on preoperative leak point pressures before TVT placement and postoperative leak point pressures on failed cases of TVT.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE OF PERCUTANEOUS VAGINAL TAPE PLACEMENT

Midurethral Sling

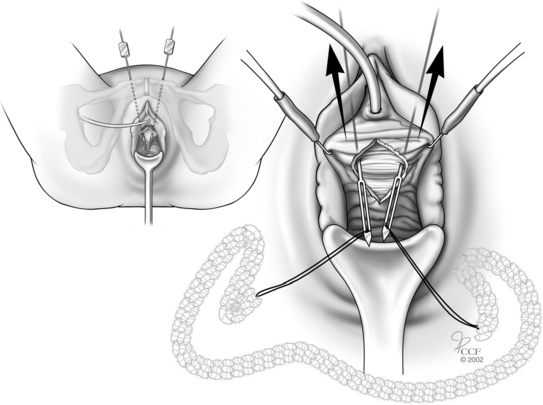

Obtain vaginal exposure via the dorsal lithotomy position. Use a marking pen to draw the abdominal percutaneous puncture and midurethral vaginal wall incision sites. Place a 16-Fr urethral catheter into the bladder (Fig. 43-1).

Figure 43-1 Marking of a midline anterior vaginal wall incision over the mid-urethra.

(Courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, copyright 2002.)

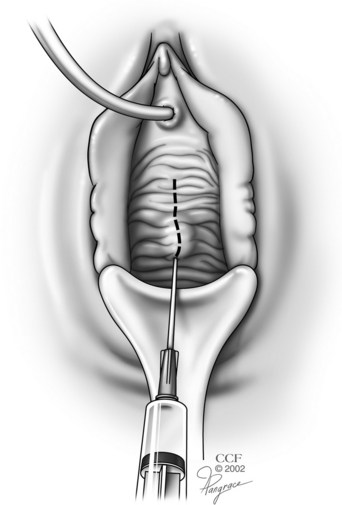

Vaginal Incision

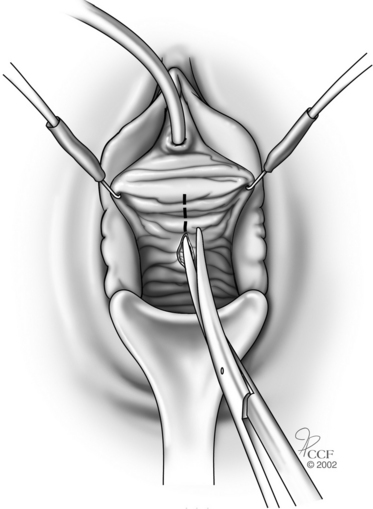

Use a scalpel to make a midline anterior vaginal wall incision at the level of the mid-urethra. Develop a pocket of space at the level of the mid-urethra between the vaginal wall and underlying urethral and paraurethral tissue by dissecting the vaginal wall tissue off laterally with the curved Mayo scissors from the 1.5- to 2.0-cm midline incision to the lateral anterior vaginal sulcus. No true entry into the retropubic space is required (Fig. 43-2). When the pocket of space is completed laterally to the junction of the inferior aspect of the pubic ramus and the urethropelvic complex (Fig. 43-3), one can proceed with antegrade passage of the needle carrier.

Figure 43-2 Development of a suburethral anterior vaginal wall pocket.

(Courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, copyright 2002.)

Figure 43-3 Suburethral pocket opened to confluence of endopelvic and periurethral fascia.

(Courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, copyright 2002.)

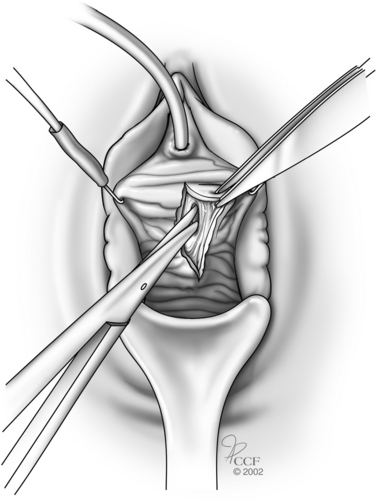

Before the percutaneous ligature carrier is passed (Fig. 43-4), the bladder should be emptied of all fluid. The patient’s position on the operating table should result in placement of the symphysis pubis in a near-vertical plane; this usually means keeping the patient’s torso and head in a level horizontal position or slightly in a Trendelenburg position.

Small (5 mm) puncture sites using the no. 15 scalpel blade through the abdominal skin overlying the top of symphysis should be made on either side of a finger placed in the midline. This maneuver allows easier manipulation of the ligature carrier for the antegrade approach by avoiding any resistance at the skin level. It also provides a visual location for avoiding perforation of the skin and rectus fascia too laterally for both approaches, which could lead to the reported complication of ilioinguinal nerve or inferior epigastric vascular damage. Attention to staying on the posterior or back side of the symphysis is required to prevent entering the rectus muscle and fascia too far cephalad from its insertion on the symphysis. Furthermore, passage anterior to the symphysis is not recommended at the present time with this approach. By taking the time to create the pocket of space at the level of the mid-urethra and to identify the correct anatomic structures (urethra medially, arcus tendineous levator ani laterally, and the inferior aspect of the pubic ramus and urethropelvic complex anteriorly), one facilitates the safest movement of the Stamey needles in a vertical direction that minimizes the likelihood of urethral or bladder injury.