Chapter 78 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY, DIAGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT OF DEFECATORY DYSFUNCTION

The domain of defecatory disorders is vast, and their treatment can be frustrating for the surgeon and the patient. Except for straightforward surgically correctible disorders, most diseases in this category have many causes and need treatment that encompass medical, behavioral, and surgical modalities. These patients often go from physician to physician seeking a cure for these complex disorders.

DIAGNOSIS

Anal Physiology Testing

Anal physiology testing has two parts. The first is manometry, which records resting and squeeze pressures and evaluates rectal sensation by documenting the time of first sensation of rectal filling and maximum tolerated volume. Rectal compliance also can be calculated. Paradoxical pressures in the rectum can be recorded during squeeze and strain, and they also can be demonstrated on electromyography by identifying the external anal sphincter contraction. Balloon expulsion tests can demonstrate rectal inertia or loss of coordination among the rectum, pelvic floor, and anal sphincters.

Anorectal Ultrasound

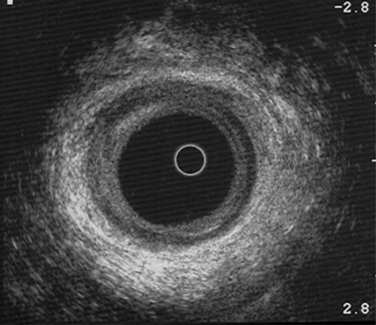

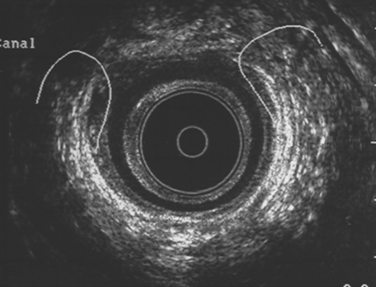

Endoluminal ultrasound is the single most important test to demonstrate sphincter defects. The normal sphincter is shown in Figure 78-1. Sphincter defects may be those of the internal anal sphincter or external anal sphincter (Fig. 78-2), or both (Fig. 78-3). Thinning of the internal anal sphincter is easily demonstrable. After sphincteroplasty, the repaired sphincter can be evaluated with this test.

Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a test that replaces the defecating proctogram. Contrast is instilled in the vagina and rectum, and serial MR images are taken with the patient straining. Newer imaging techniques use upright MRI scans with the patient seated and evacuating in the sitting position. This test can evaluate pelvic descent, rectal diameter before and during straining, the width of the pelvic hiatus, presence of enteroceles and sigmoidoceles, and prolapse of the uterus and bladder.1 It may become the confirmatory test for obstructive defecation. Cine radiography can give a dynamic picture of the process of evacuation, and it can demonstrate prolapse of the anterior wall of the rectum.

FECAL INCONTINENCE

Pathophysiology

Injury to the muscle complex or the nerves that supply them can result in a loss of continence. The most common etiologic factor is childbirth injury. Other causative factors are listed in Table 78-1.

Table 78-1 Causes of Fecal Incontinence

| Sphincter injury |

| Childbirth trauma |

| Surgical trauma |

| Rectal injury, traumatic |

| Irradiation |

| Congenital causes |

| Imperforate anus |

| Colonic causes |

| Fecal impaction |

| Colitis, proctitis |

| Rectal prolapse |

| Tumors |

| Decreased rectal compliance |

| Neurogenic causes |

| Peripheral disorders (e.g., diabetes) |

| Central disorders |

| Trauma |

| Stroke |

| Tumors |

| Dementia |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Functional causes |

| Other causes |

| Diarrhea |

| Myopathy |

Treatment of Fecal Incontinence

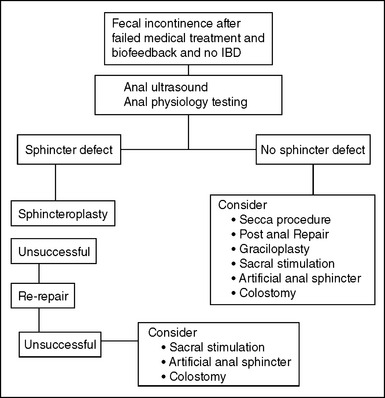

The treatment of fecal incontinence is based on the severity of symptoms, the anatomy of the sphincter mechanism, and the presence of nerve damage. An algorithm for management is provided in Figure 78-4, but treatment options depend on the availability of certain procedures and on the patient’s comorbidities.

Treatment of Minor Incontinence

A thorough history and physical examination are the first step in treatment to rule out inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel disease, and neurologic disorders. Minor incontinence can be treated with medical management2 using bulking agents, which can change the consistency of stool and lead to evacuation as a mass movement. They are started in small doses to prevent abdominal distention and bloating, and they are gradually in-creased to achieve the desired effect. Other agents that are used slow the gastrointestinal motility. They tend to constipate the patients because they decrease the bulk of the stool during the increased transit time. Loperamide hydrochloride (Imodium) is the commonly used medication, and it may be started in doses of 2 mg before breakfast and advanced to a maximum of 16 mg daily as warranted. Diphenoxylate hydrochloride (Lomotil) is another drug that may be used, especially if diarrhea is the main symptom. It is started in doses of 1 tablet once or twice daily and may be advanced to 1 or 2 tablets three or four times daily.

Amitriptyline3 has been used for idiopathic fecal incontinence. It acts through an anticholinergic mechanism, increasing intrarectal pressures. Phenylephrine cream is an α1-adrenergic blocker that has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Used in some studies in strengths of 10% to 40%, it has been shown to increase resting pressures for 1 to 2 hours.4

Biofeedback and Kegel Exercises

Biofeedback training consists of retraining the patient’s re-sponse using visual, auditory, and sensory stimuli. It consists of strength training of the external sphincter, retraining the sphincter to coordinate rectal distention with external anal sphincter contraction, and sensory training of the rectal mucosa to be able to sense earlier when the rectum receives contents. It is done in the office by a trained therapist using the electromyographic apparatus to retrain and strengthen the sphincter, and a rectal balloon is used for sensory stimulation training. Some studies have shown improvement after biofeedback therapy.5 Biofeedback has been shown to benefit patients after sphincter repair.6

Treatment of Moderate Fecal Incontinence with an Intact Sphincter

Secca Procedure

The procedure is done under conscious sedation. After local anesthesia is injected, radiofrequency is delivered by means of a specialized probe that contains needles that pierce the mucosa and submucosa. In about 64 separate punctures, the radiofrequency is applied beneath the mucosal surface. Contraindications to this procedure include inflammatory bowel disease, a history of depression, collagen vascular disease, acute infections, pudendal neuropathy, and a history of pelvic irradiation.7

Sacral Stimulation

Sacral nerve stimulation is FDA approved in the United States for stress urinary incontinence, and it is being evaluated under a research protocol for fecal incontinence. It produces constant stimulation of the sacral nerves, resulting in an increase in resting tone and squeeze pressures. In this procedure, a temporary stimulator is implanted as a first step, and if the patient improves, a permanent device is implanted. It has gained popularity in Europe, where it has been available for many years.8

Treatment of Moderate to Severe Fecal Incontinence due to a Defect in the Sphincter Mechanism

Overlapping Sphincter Repair: Sphincteroplasty

The sphincter ends that have been sufficiently mobilized to allow overlapping of the muscle are grasped. Some authorities10,11 advocate merely approximating the muscles, but if possible, overlapping the muscle ends is preferred using 2-0 polyglactin sutures, placing mattress sutures for the sphincteroplasty. Approximately six sutures (three on each side) are used. The repair tightens the anal canal such that only an index finger may be admitted. During the procedure, the wound may be irrigated with antibiotic solution. The skin edges are closed in a V-Y fashion, starting laterally and leaving the center open for drainage. If there is a significant amount of dead space, a 0.5-inch Penrose drain can be inserted and then removed postoperatively.

A diverting stoma is used at the discretion of the surgeon. Preoperatively, this should be discussed with patients who have had previous failed repairs, have concomitant inflammatory bowel disease, have severe diarrhea, or need an extremely complicated repair. A stoma does not ensure success but may aid a successful outcome in such patients.12

Initial functional improvement can be anticipated in 80% to 90%13–15 of patients. Pudendal nerve damage is associated with suboptimal results.13 Age does not seem to significantly affect results,12 although erratic bowel problems such as urgency and diarrhea may lead to continued incontinence. Wound infection occurs in up to a fourth of patients15 but does not usually adversely affect the outcome unless the sphincter repair sutures become disrupted. Complete disruption of the skin sutures usually heals by secondary intention with adequate wound care.

Long-term follow-up suggests that about 40% of patients undergoing a repair are expected to be continent without further surgery.16 In patients needing a repeat overlapping sphincter repair due to disruption of the initial repair, evidence suggests that satisfactory outcome can be achieved.17

Dynamic Graciloplasty

Graciloplasty is no longer available in the United States, because the stimulator is no longer supplied by the manufacturer. Indications for this procedure include sphincter defects from obstetric or traumatic injury, congenital defects, and idiopathic incontinence. Contraindications are diseases with a neurologic basis, such as multiple sclerosis. Dynamic graciloplasty has been an excellent choice for patients who have no alternative but to have a stoma. Success has been reported in about 40% to 65% patients undergoing this procedure.18,19

Treatment of Moderate to Severe Incontinence with an Intact Sphincter and No Neurologic Deficit