the paraurethral (Skene) glands, represent the homolog of the prostate and are located on each side of the urethra. The paraurethral glands share a common duct on each side, the paraurethral ducts, which enter the urethra near the external urethral orifice. The female urethra receives blood circulation from the vaginal and internal pudendal arteries and veins, while it is innervated by the pudendal nerve. Lymphatic drainage courses to the internal iliac and sacral lymph nodes, with some drainage to the inguinal lymph nodes.

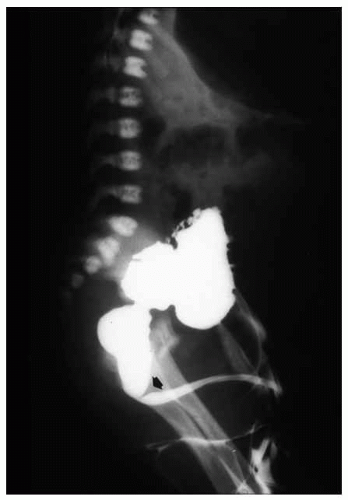

frequently involving external genitalia and gastrointestinal tract.25 Most urethral duplications occur in the same sagittal plane (dorsal or ventral to the urethra), and they are classified as complete (with one or two orifices) or incomplete (with a distal or proximal blind end) or may be part of an incomplete or complete caudal duplication (Fig. 7-3).26 This anomaly may be asymptomatic or be associated with infections, incontinence, or even double stream of urine if the duplication is complete.26 Histologically, the anomalous urethra is lined by urothelium that may be associated to variable degrees of inflammation in the lamina propria. In symptomatic cases, surgery is the treatment of choice.

lined by benign-appearing squamous epithelium without viral cytopathic effect; they are also HPV negative by in situ hybridization studies.53 As in other sites, HPV-associated squamous dysplasia may progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma, often associated with high-risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, or 35. Therapy for squamous intraepithelial lesions is typically ablative, by surgery, laser, or topical agents.54

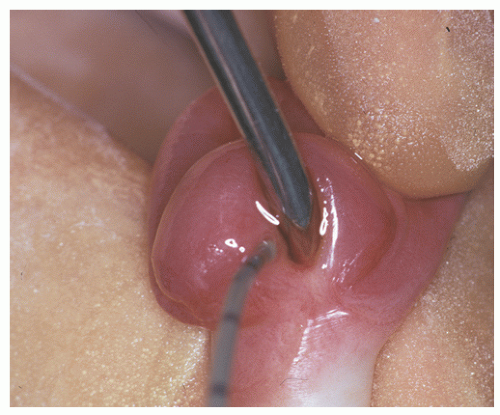

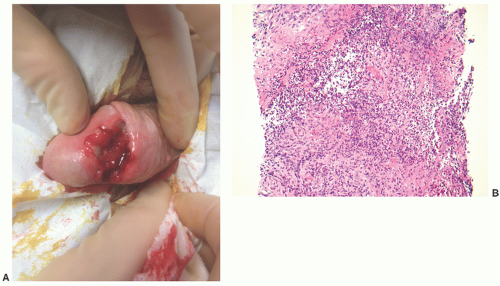

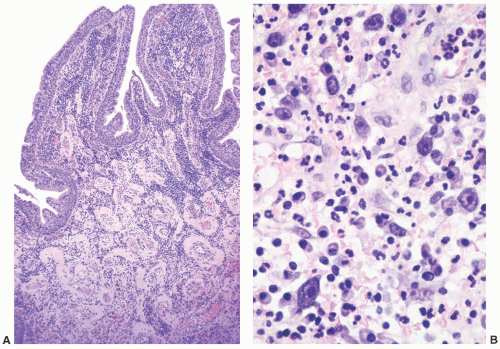

and clinically misdiagnosed as carcinoma, especially in the penile urethra where Wegener granulomatosis may present as painful fungating mass or extensive ulceration (Fig. 7-7A). Histologic examination may not be diagnostic, only showing extensive necrosis as oftentimes the first diagnostic procedure is a biopsy (Fig. 7-7B). However, the classical morphology includes geographic areas of eosinophilic necrosis associated with palisading histiocytes. Vascular involvement typically shows granulomatous vasculitis with giant cells, but it is not always seen. Methotrexate is the treatment of choice, but patients still often require surgery due to local complications.66, 67, 68 The urethra is the least common site of involvement by sarcoidosis in the genitourinary tract. On gross examination, it may grossly simulate cancer.69 The morphology is that of noncaseating loose granulomas, but this histologic appearance is nondiagnostic and can be seen in infections and other processes including malignancy (typically at its periphery). However, these patients often have a well-established history of sarcoidosis.70

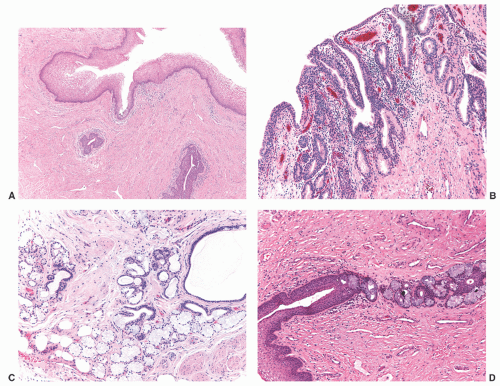

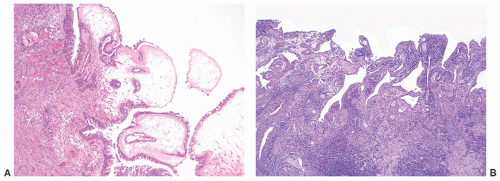

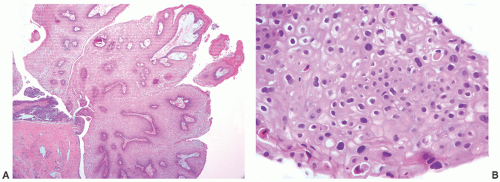

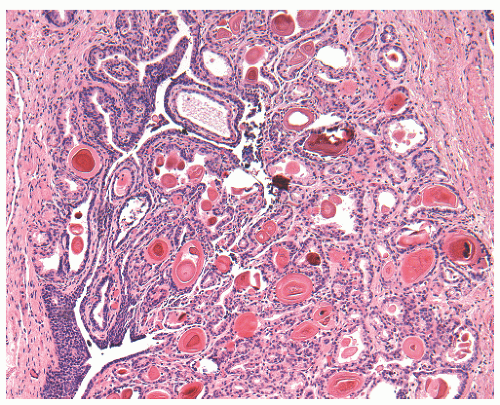

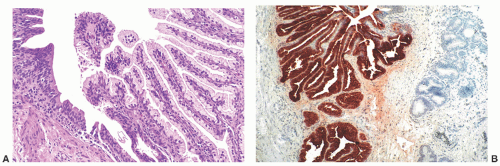

nests of invaginated urothelium in the lamina propria. The nests typically have smooth, rounded contours and are often clustered in groups, but the connection with the overlying urothelium may not be identifiable (Fig. 7-8A). They are usually located in the superficial lamina propria, but they may deeper however, they are never present in the muscularis propria.

Table 7-1 ▪ URETHRAL POLYPS AND CYSTS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

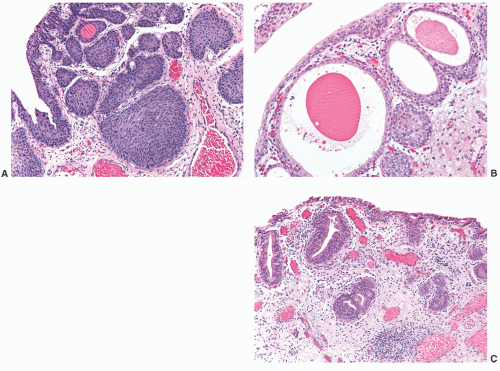

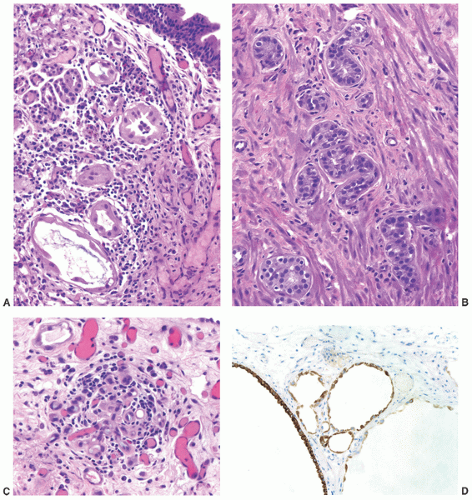

children and females, in the latter frequently in association with a urethral diverticulum.120, 121, 122 The urethra is the second most frequent location (15%) following the bladder.123 In most instances, nephrogenic adenoma is an incidental finding at cystoscopy performed for other reasons, but if large it may cause symptoms related to obstruction. In these cases, it may be potentially confused with a malignant tumor, most commonly a low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. On microscopic examination, nephrogenic adenoma shows tubular, cystic, papillary, and rarely solid growths, but not infrequently an admixture thereof.122,123 The tubules vary in size and shape and may be solid on rare occasions (Fig. 7-12A). An appreciable basement membrane may be seen surrounding some of the tubules. Of note, the tubules of nephrogenic adenoma may be intermixed with muscle fibers of the muscle fibers present in the wall of the prostatic urethra when the specimen is obtained from transurethral resection (Fig. 7-12B).120,124,125

Recently, a fibromyxoid variant of nephrogenic adenoma has been reported characterized by very small tubules associated with prominent fibromyxoid background that may closely mimic the appearance of an infiltrating carcinoma (Chapter 5).126 Cysts are frequently admixed with tubules, but they are not striking in most cases (Fig. 7-12A). The papillae are simple without branching, and they are rarely seen in the absence of tubules. The solid pattern is very rare and, when present, typically represents a minor component. The cells of nephrogenic adenoma are cuboidal to columnar to flattened with variable eosinophilic to slightly clear and granular cytoplasm, and exceptionally they may be spindled.126 Hobnail cells are typically present, most often lining the cysts, but are rarely conspicuous.123,127 The cells lining tiny tubules have a compressed nucleus with a single vacuole containing basophilic material resembling signet ring cells (Fig. 7-12C). The nuclei are round to oval with minimal cytologic atypia. Nucleoli are inconspicuous, and mitotic figures are rare (<1/10 HPFs) and seen in 5% of the lesions.123 The term “atypical nephrogenic adenoma,” has been used for lesions characterized by nuclear enlargement, nuclear hyperchromasia, and enlarged nucleoli.127 There is no known clinical or biologic significance to this designation. The stroma associated with nephrogenic adenoma is focally edematous and contains variable amounts of inflammatory cells. Stromal calcification may be seen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree