Chapter 23 Pancreaticobiliary Stent Removal

Migrated and Nonmigrated

Patients with pancreaticobiliary obstructive diseases are suitable for endoscopic stent placement as definitive treatment or as a bridge to surgery. As a matter of fact, endoscopic stent placement has proved to be as effective as surgical drainage for the treatment of malignant jaundice but with lower morbidity rates confirmed in several randomized controlled trials.1 Stent placement can provide partial or definitive pancreaticobiliary drainage while avoiding the morbidity associated with percutaneous therapy or surgery and frequently providing better quality of life compared to other alternatives.1 The goal of endoscopic pancreaticobiliary stent placement is to provide biliary or pancreatic decompression and drainage with relief of obstructive symptoms.

Removal of pancreaticobiliary stents becomes necessary in patients with benign disease, in long-surviving patients with nonresectable malignant disease, and in patients with stent-related adverse events. The first case report of an uncovered self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) removal was published in 1999 and was achieved using a forceps to remove the metal fibers of the stent one by one.2 Subsequently, the first removal of a migrated, partially covered SEMS was described in 20033 and was performed in two patients with malignant disease. Extraction was accomplished uneventfully using a snare. The time frame to remove a stent varies depending on the organ drained (bile duct or pancreas), the type of stent (plastic or metallic), the number of stents placed,4 and the presence of symptoms that can raise suspicion of a stent adverse event.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Removal of Biliary Stents

Removal of plastic biliary stents (PBS) is usually performed with ease, especially if it is carried out within several months of placement. Successful removal rate of covered SEMS (C-SEMS) is reported to be around 95%,5 but removal of uncovered SEMS (U-SEMS) is usually very difficult, if not impossible, because they become embedded in tissue regardless of whether the disease is benign or malignant. Thus the reported successful removal of U-SEMS ranges between 0% and 38%.6 There are several well-known factors related to difficult SEMS extraction:

Type of SEMS. As noted above, U-SEMS are much more difficult to retrieve than C-SEMS, but unsuccessful removal in the latter can also reach 22%.5,7

Type of SEMS. As noted above, U-SEMS are much more difficult to retrieve than C-SEMS, but unsuccessful removal in the latter can also reach 22%.5,7

Duration of treatment. In a recent study evaluating the efficacy and safety of endoscopic SEMS retrieval in 19 patients, removal of SEMS was impossible in five of them; four of these patients had a C-SEMS and one had a U-SEMS.5 The authors reported that the mean indwelling period of removable SEMS was shorter than that of nonremovable SEMS, suggesting that the length of the implantation may affect the success rate of SEMS removal.

Duration of treatment. In a recent study evaluating the efficacy and safety of endoscopic SEMS retrieval in 19 patients, removal of SEMS was impossible in five of them; four of these patients had a C-SEMS and one had a U-SEMS.5 The authors reported that the mean indwelling period of removable SEMS was shorter than that of nonremovable SEMS, suggesting that the length of the implantation may affect the success rate of SEMS removal.

Structural properties of the stent. In the experience of some authors, differences in shortening and straightening of the stent have been related to the structural properties of the stent and associated with the ease of extraction. These authors described accordingly that removal of Niti-S Biliary ComVi stents (Taewoong Company, Seoul, South Korea) was slightly more difficult than Wallstent removal (Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo).5

Structural properties of the stent. In the experience of some authors, differences in shortening and straightening of the stent have been related to the structural properties of the stent and associated with the ease of extraction. These authors described accordingly that removal of Niti-S Biliary ComVi stents (Taewoong Company, Seoul, South Korea) was slightly more difficult than Wallstent removal (Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo).5

Tissue ingrowth. Tumor ingrowth in U-SEMS is common, with the stent becoming embedded in the lesion and thus hindering or even preventing retrieval of the stent. Although C-SEMS are not affected by this phenomenon, it is also common in the uncovered part of partially covered SEMS (PC-SEMS).

Tissue ingrowth. Tumor ingrowth in U-SEMS is common, with the stent becoming embedded in the lesion and thus hindering or even preventing retrieval of the stent. Although C-SEMS are not affected by this phenomenon, it is also common in the uncovered part of partially covered SEMS (PC-SEMS).

On the other hand, extraction of PBS is hindered when proximal migration occurs. Some factors that make retrieval more challenging in this situation are8:

Migration of the stent upstream from a stenotic region

Migration of the stent upstream from a stenotic region

Inconsistency between the biliary stent and its axis in patients with no biliary dilation

Inconsistency between the biliary stent and its axis in patients with no biliary dilation

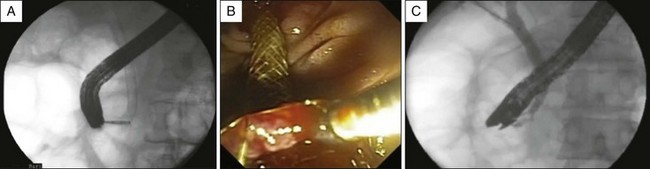

Stent with the lower end digging into the bile duct wall (Fig. 23.1)

Stent with the lower end digging into the bile duct wall (Fig. 23.1)

Distally migrated stents generally pass through the intestine without any problems, although retrieval may be necessary in some cases. The endoscopic removal rate when the stent is accessible is high and can reach 100%.9 Proximally migrated stents are more difficult to retrieve, but success rate of endoscopic removal ranges from 71% to 90%. If the endoscopic retrieval procedure is unsuccessful, either surgery8,10 or the placement of a second stent leaving the first one in place is required in order to allow access and subsequent retrieval of the migrated stent.

Indications and Contraindications

1. Resolution of the biliary disease. Once the beneficial effect of the stent is no longer needed it should be removed. In those stents placed to treat biliary stenoses, especially those related with chronic pancreatitis, it is recommended to maintain the stent in place for a longer period in order to prolong its beneficial effect. In most series, resolution of the disease is the most common indication for stent removal,11,12 although some identify the leading indication as stent occlusion. For example, in a multicenter analysis of safety and outcome of removal of FC-SEMS in 37 patients published recently, occlusion by debris is the cause of removal in 46% of patients, while completion of therapy reaches 40%.13

2. Malfunction of the stent. Two main circumstances are associated with malfunction of a biliary stent, including occlusion by debris or tissue hyperplasia and migration of the stent.

Occlusion of the stent entails development of cholangitis or jaundice. PBS become obstructed by biofilm comprised primarily of protein, bilirubin, and crystals but almost no cholesterol.14 The origin of this biofilm is not clear, but it has been postulated that it arises from bacterial products given that stents perfused with sterile bile do not accumulate sludge.15 The biofilm permits the bacteria to adhere firmly to the stent and thus continuous deposition of bacterial degradation products and growth of bacterial colonies can eventually lead to complete occlusion of the stent.15,16 Treatment of PBS occlusion entails retrieval of the occluded stent followed by single or multiple PBS or SEMS placement depending on the indication.

With respect to SEMS, tumor ingrowth is usually the cause of U-SEMS occlusion while tumor overgrowth is responsible for the occlusion of C-SEMS, and sludge can cause occlusion of both types of SEMS.17 The endoscopic therapy of a metal stent occluded by debris is balloon sweep, although short-term recurrence of obstruction is high, or alternatively placing a coaxial stent inside the clogged one.18,19 Occlusion of SEMS by tumor ingrowth or tissue overgrowth can be managed by placing one or multiple PBS or a second coaxial SEMS. There are some retrospective studies that evaluate this issue with contradicting results, although in the majority of these studies no significant differences are found when comparing the insertion of coaxial PBS or SEMS to achieve biliary drainage.17 Some authors support the extraction of the occluded stent with deployment of a new SEMS.5,20,21

The other main cause of biliary stent malfunction is migration. Complete external migration usually causes recurrence of symptoms such as cholangitis or jaundice, but it may be asymptomatic in those patients in whom completion of the therapeutic effect has been achieved (e.g., in benign stenoses). If this is not the case, a new stent must be inserted. The externally migrated stents generally pass through the intestine without problems and endoscopic removal is not needed. Infrequently, stents can become trapped in the bowel, leading to adverse events that may be lethal.9 External migration can be incomplete and stents might wedge themselves in the contralateral duodenal wall. In such cases, apart from cholangitis and jaundice, bleeding or even perforation can occur. Internal migration occurs in 5% of cases, half of them being asymptomatic9 and are usually more difficult to solve. The reported success rate of retrieval of proximally migrated stents ranges from 71% to 90%.9,22,23

3. Adverse events of stent placement. Clinical symptoms related to stent insertion can be considered an indication to remove the recently placed stent. Acute cholecystitis has been reported as a specific adverse event of C-SEMS deployment,24 but in our experience it can also occur after placement of PBS and U-SEMS. Acute pancreatitis can also occur after placement of C-SEMS or U-SEMS, forcing removal of the stent in some cases.20,24 Sphincterotomy prior to placement of a C-SEMS is recommended in order to prevent pancreatitis,7 and prophylactic pancreatic stents can also be inserted with this aim. Acute cholecystitis can be prevented by placing a thin plastic stent (i.e., a pancreatic stent) partially inserted in the cystic duct prior to the deployment of C-SEMS, but when this is not possible adjustment of the proximal end of the stent below the communication of the cystic duct with the common bile duct is recommended, if possible. Abdominal pain is also rarely reported after placement of biliary stents.13,20,25 In a prospective evaluation of the efficacy of C-SEMS in benign biliary strictures including 79 patients, abdominal pain after C-SEMS placement forced stent removal in two patients (2.5%).11

Other indications for stent removal have been randomly described. Kahaleh et al. (2004) retrieved one U-SEMS and another PC-SEMS to facilitate management of bleeding.20

Strict contraindications for stent removal have not been described, except for when endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is contraindicated. The development of duodenal stenoses after placement of a biliary stent in patients with benign or malignant biliary occlusion may therefore be considered a contraindication for endoscopic removal attempts of the stent. In the previously mentioned series on retrieval of C-SEMS in 79 patients, this was the reason that precluded initial retrieval in two patients with benign biliary stenoses who thus needed enteral feeding until the duodenal edema that prevented duodenoscope passage completely resolved.11 Similarly, some retrieval techniques may be contraindicated in individual patients: Extraction of U-SEMS by means of removal of individual guidewire filaments is contraindicated in patients with coagulopathy, and extraction of intraductal migrated stents with foreign body forceps is discouraged in patients with pericholedochal varices or severe portal hypertension. Furthermore, removal of the stent should not be attempted in the following situations:

1. Incomplete therapeutic effect and absence of adverse events related to the stent. The stents should not be removed before the beneficial effect is completed if the patient is asymptomatic and the stent is correctly in place. Exceptions to this are scheduled stent exchanges recommended to avoid stent occlusion.

2. Short life expectancy in an asymptomatic patient. In patients with malignant disease and short life expectancy without symptoms attributable to the biliary stent, there is no need to remove it. It is reasonable not to try to extract even proximally migrated biliary stents in this situation.

Time for Stent Removal

The recommended period over which biliary stents should be left in place depends largely on the type of stent and the indication for which the stents are being used. Regarding the type of stent, PBS dysfunction occurs on average after 3 to 4 months, with 30% of PBS becoming occluded after 3 months and 70% after 6 months. If the treatment is not completed by then, stent exchange is needed, an event that occurs in approximately 30% to 60% of cases.26,27 U-SEMS should be deployed only in patients with malignant disease or patients with benign disease but life expectancy less than 2 years,28 namely in those patients in whom it is not anticipated that removal of the stent will be necessary. In a series of 18 patients considered for SEMS removal, this was successfully achieved in 17 (94%).20 Four of these stents were U-SEMS and all could be removed, two after more than 10 months. One C-SEMS could not be extracted because of tumor overgrowth and postbulbar obstruction that prevented access to the papillary orifice.

With regard to the indication for stenting, the treatment of benign biliary stenoses requires keeping the stent in place for the longest period, with no less than 1 to 2 years recommended.29 If PBS are used, stent replacement should be performed every 3 months until the end of treatment. C-SEMS can remain in place for a prolonged period before removal. Some authors have stated that removal of PC-SEMS beyond 6 months is feasible yet more challenging, so probably this type of stent should be retrieved or replaced before 6 months.11,30 Currently, U-SEMS should not be considered as a temporary treatment and should be deployed only in patients with malignant disease in whom no need for retrieval can be anticipated. Removal of these stents is considered only when they become occluded by debris or tissue ingrowth. The median time of correct function of U-SEMS has been estimated at 20 months (2 weeks to 60 months) before reintervention is needed, which is performed mostly due to stent obstruction.12 Unfortunately, at the time of stent deployment it is not always possible to know the prognosis of the disease and a disease that initially looks advanced may reveal itself resectable after a complete staging workup. In this situation, U-SEMS generally can be removed with ease within 2 weeks after insertion in order to facilitate surgery.6

Techniques

For nonmigrated stents and distally migrated stents, grasping the stent and subsequently removing it through the working channel of the endoscope or simply taking out the endoscope while holding it is adequate. Removal of proximally migrated stents is far more difficult and sometimes special devices such as Fogarty balloons are needed. Furthermore, the two-dimensional fluoroscopy used for this approach requires a skillful endoscopist. In these cases, cannulation and indirect intraductal manipulation of the devices is required, which hinders the extraction, and its removal is facilitated by performing sphincterotomy.9

An overview of the more common techniques used for stent removal follows.

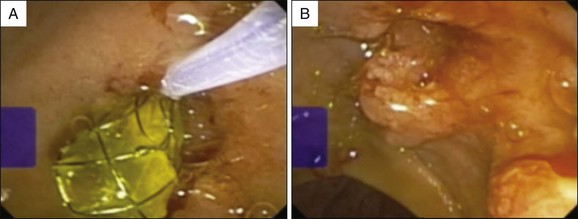

Direct Grasping Technique

The direct grasping technique is a simple technique that involves reaching the second duodenal portion with an endoscope and maneuvering the snare to engage the distal intraduodenal end of the stent, which is then tightly grasped and pulled straight out of the bile duct. In our experience, just like that of other authors,13,22,23 this is the most commonly used technique. A Dormia basket or foreign body forceps can also be used instead of a polypectomy snare, and are considered techniques of choice by other authors.9 See Figs. 23.1 and 23.2.

These grasping techniques are also used to retrieve distally migrated stents. In a recent multicenter study, endoscopic removal of distally migrated stents was attempted in 17 of 30 patients with this adverse event and was successful in all of them. Retrieval with snare was employed in 11 of these patients and retrieval with basket was employed in the remaining 6 patients.9

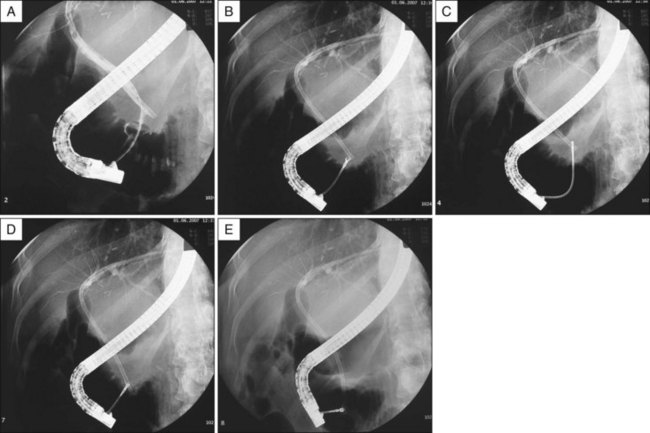

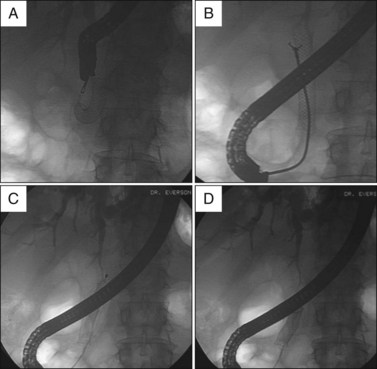

Indirect Grasping Technique

The indirect grasping technique has also been used successfully in proximally migrated stents (Figs. 23.3 and 23.4). In this situation the devices must be inserted into the bile duct through the papilla, advanced to the distal end of the stent, and then maneuvered to grasp and pull the stent down until it falls into the duodenum. The procedure is then most commonly completed by grasping the stent with forceps, although some authors prefer using a snare or basket to retrieve the migrated stents.31

Lasso Technique

The lasso technique involves inserting a guidewire through the lumen of the stent and then inserting a partially opened polypectomy snare over the guidewire to grasp the stent. Once the stent is encircled tightly by the snare it is pulled out over the guidewire, thereby keeping the access to the bile duct without further need of cannulation. Special care must be applied in order not to remove the guidewire from the bile duct while removing the stent, but in our experience this is uncommon. This technique was originally described by Sherman et al.32 and required cannulation of the stent with a guidewire, but recent experiences using variations of this technique by cannulating the duct alongside the stent instead of the stent lumen have been reported.33 The main advantage of the lasso technique is that it preserves the access to the bile duct, thereby avoiding the need for recannulation in order to review the bile duct or insert a new stent over the guidewire. This is especially useful when difficult cannulation is anticipated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree