Chapter 32 Pancreas Divisum, Biliary Cysts, and Other Congenital Anomalies

Ampullary Anomalies

Ectopic Major Papilla

The major papilla, typically located in the mid or distal second duodenum, is occasionally located in the third duodenum.1 Ectopic distal location of the ampulla is associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction, congenital biliary dilation, and biliary cysts.2 The distal displacement of the papilla may correspond to the length of an abnormally long common channel3 and may reflect failure of the ducts to migrate normally into the duodenum during embryologic development. Rarely the major papilla may be located in the duodenal bulb.4 Double papilla of Vater has been described.5 When the papilla is in an anomalous location the oblique intramural course of the bile duct is often absent,6 leaving less room for endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy.

Anomalous Pancreaticobiliary Junction

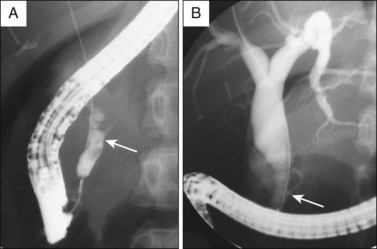

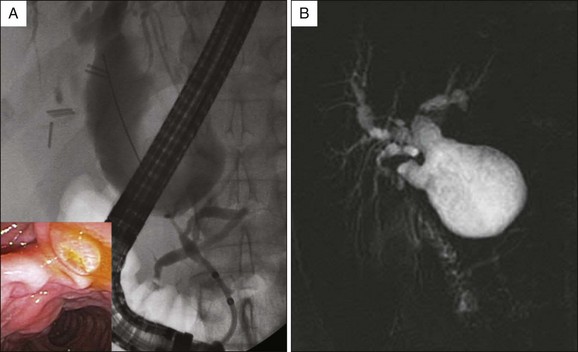

The bile duct and pancreatic duct typically form a common channel of 1 to 6 mm in the papilla of Vater.7 Less commonly a long common channel is present (Fig. 32.1), which may be termed anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ). Synonyms include anomalous union of pancreaticobiliary duct,8 anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary duct, and anomalous pancreaticobiliary union.9 APBJ may be subdivided into pancreaticobiliary malunion (PBM), in which the junction of the bile duct and pancreatic duct lies outside the duodenal wall with free communication between the ducts when the ampullary sphincter is contracting,10 and high confluence of pancreaticobiliary ducts (HCPBD), in which contractions of the duodenal wall or sphincter interrupt communication between the ducts.11 APBJ can also be subclassified according to the presence or absence of pancreas divisum, a dilated common channel, and an acute angle between the bile duct and pancreatic duct.12 These findings may influence treatment strategy in symptomatic patients, particularly those with biliary cysts.

APBJ promotes reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary system and appears to be a risk factor for the development of malignancy in a biliary cyst as discussed below. Patients with APBJ and no biliary cyst not only have an increased risk of gallbladder cancer but also develop gallbladder cancer at an earlier age (Fig. 32.2).13,14 The risk of gallbladder cancer in patients with HCPBD may be somewhat lower than the risk seen in PBM.11 Either way, the finding of an isolated APBJ should prompt consideration of prophylactic cholecystectomy. Unexplained thickening of the gallbladder wall identified on transabdominal ultrasonography has been associated with underlying APBJ.15

Biliary Anomalies

Variations of Bile Duct Anatomy

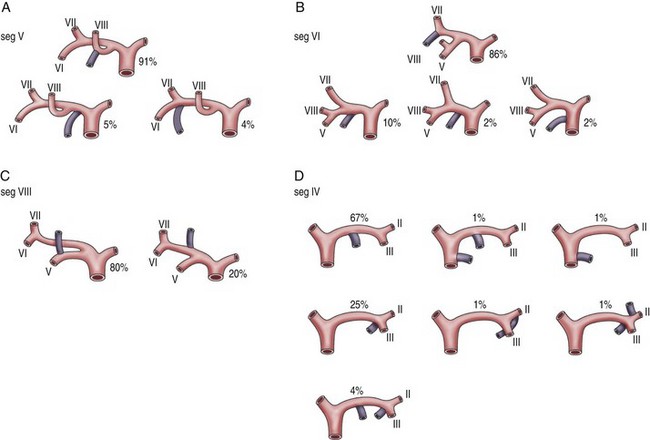

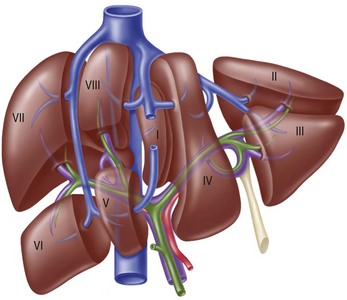

Coiunaud16 described the liver as being composed of four sectors, defined by the three hepatic veins.17 The four sectors can be further subdivided into eight segments, which are drained by segmental bile ducts (Fig. 32.3). Ducts from segments II, III, and IV form the left hepatic duct, and ducts from segments V, VI, VII, and VIII form the right hepatic duct. The right and left hepatic ducts then form the biliary confluence or bifurcation. The caudate lobe (segment I) is typically drained by several short, small ducts into both the right and the left hepatic ducts and the caudate branches are generally not well seen during ERCP.

Fig. 32.3 Functional division of the liver into segments, according to Couinaud’s nomenclature.

(From Blumgart LH, Fong Y, eds. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Reproduced with permission.)

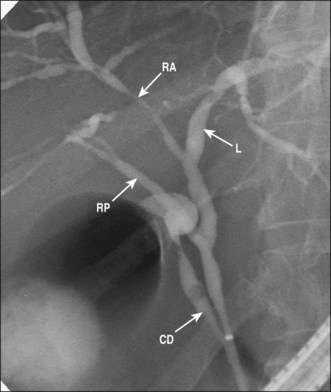

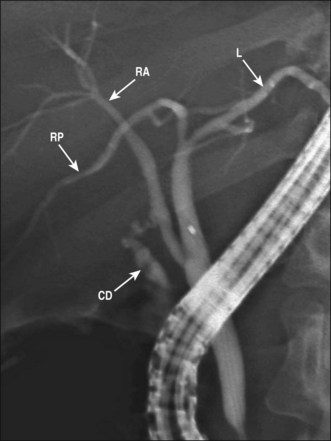

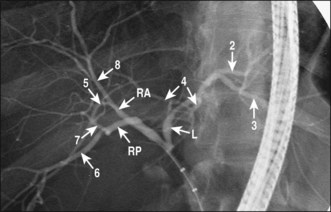

The right hepatic duct drains into the biliary confluence and is typically formed by a right anterior sectoral duct (draining segments V and VIII) and a right posterior sectoral duct (draining segments VI and VII). On cholangiography the right anterior duct has a relatively vertical and medial course and the right posterior duct has a more horizontal and lateral course (Fig. 32.4; see also Figs. 32.6 and 32.7).17 Moving away from the confluence along the left hepatic duct, the first visualized branches generally drain segment IV, which may be drained by one to three segmental ducts. Moving further to the left, the left hepatic duct bifurcates into the segment II and III ducts (Fig. 32.4).17

Fig. 32.4 Normal intrahepatic ductal anatomy. Note that the right anterior duct has a relatively vertical and medial course and the right posterior duct has a more horizontal and lateral course. See also Figs. 32.6 and 32.7. L, Left duct; RA, right anterior duct; RP, right posterior duct; numbers indicate drained hepatic segments.

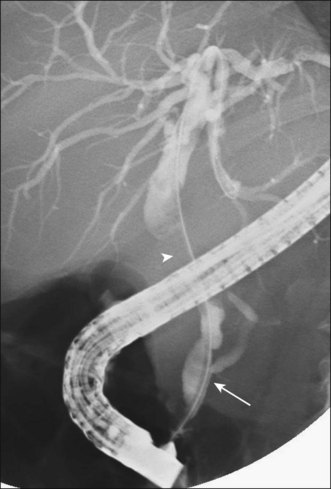

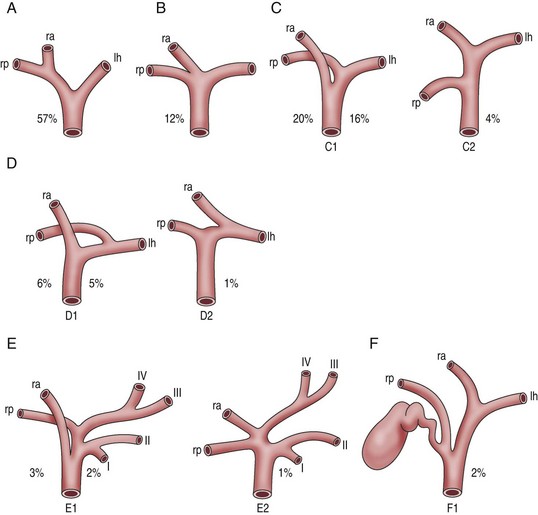

Variants of confluence anatomy are common and the normal confluence anatomy described above is seen in only 57% of persons. The most common variations involve the right anterior and posterior ducts, and are shown in Fig. 32.5. These include low drainage of one of the right sectoral ducts into the common duct (seen in 20%; Fig. 32.6), a “triple confluence” in which the two right sectoral ducts drain separately into the confluence (12%), and drainage of a right sectoral duct into the left duct (6%). In about 2% a right sectoral duct drains into the cystic duct as shown in Fig. 32.7. These variants of right duct anatomy may increase the risk of a bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. They are also important to the endoscopist when managing hilar malignant obstruction and evaluating postoperative biliary strictures and leaks. When a right sectoral duct draining into the cystic duct is divided and clipped during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, resulting in a Bismuth V ductal injury, cholangiographic diagnosis is difficult and requires a high degree of suspicion to recognize that a right sectoral duct is not visualized.

Variants of segmental duct anatomy also commonly occur (particularly segments IV, V, VI, and VIII) and are shown in Fig. 32.8. Ectopic drainage of the gallbladder and cystic duct may occur, and is discussed elsewhere.17 The cystic duct may drain into the ampulla separately from the common bile duct.18

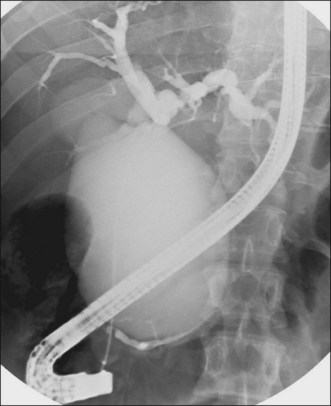

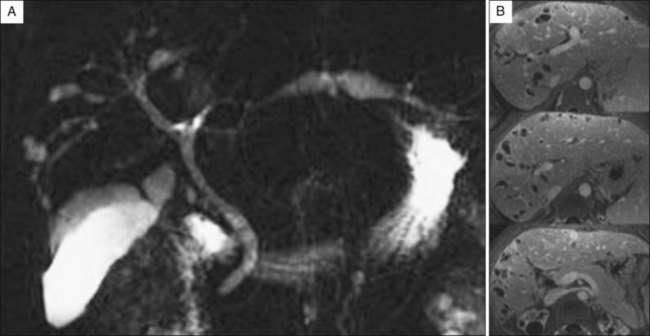

Biliary Cysts

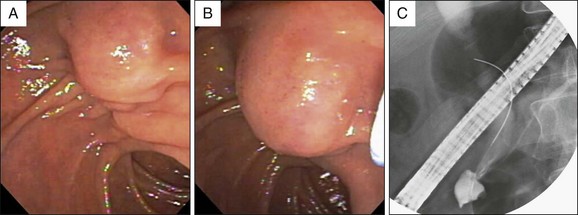

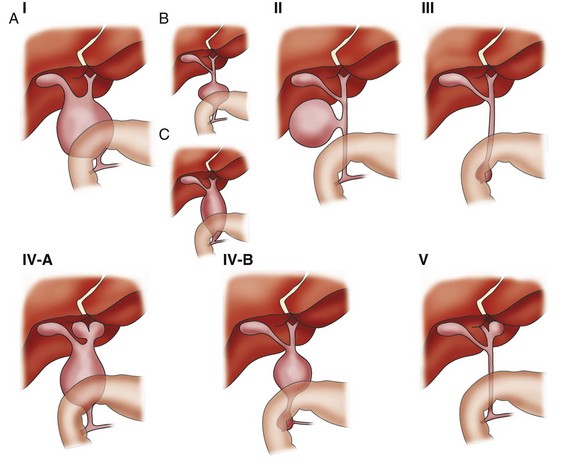

Biliary cysts, also called choledochal cysts, are cystic dilations of the biliary tree. One widely adopted classification of biliary cysts was described by Alonso-Lej and modified by Todani, and is shown in Fig. 32.9.19,20 Type I cysts, which are most common, are dilations of the common bile duct, typically in association with an APBJ. They can be subdivided into types IA, IB, and IC based on the presence or absence of an APBJ and fusiform or segmental dilation, as shown in Figs. 32.1, 32.9, and 32.10. Type II cysts are diverticula of the common duct. Type III cysts involve the major papilla and may also be termed a choledochocele or duodenal duplication (as they are often lined by duodenal rather than biliary mucosa). Type III cysts may be further subdivided into type IIIA (in which the bile duct and pancreatic duct enter the cyst proximally and the cyst drains through a separate distal opening into the duodenum; Fig. 32.11) and type IIIB (a diverticulum of the intraampullary common channel). Type IV cysts are multiple cysts located in both the intrahepatic and the extrahepatic ducts (type IVA, Fig. 32.12) or in the extrahepatic biliary tree (type IVB). Type I cysts with associated dilation of central intrahepatic ducts can be distinguished from type IVA (combined intrahepatic and extrahepatic cysts) by the presence of a distinct change in ductal caliber at the distal end of a true intrahepatic cyst.20 Type V cysts, also called Caroli disease, are segmental cystic dilatations of the intrahepatic ducts (Fig. 32.13).

Fig. 32.9 Classification of biliary cysts.

(From Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, et al. Classification of congenital biliary cystic disease: special reference to type Ic and IVA cysts with primary ductal stricture. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10(5):340-344. Reproduced with permission.)

Periampullary choledochal diverticula are small diverticular outpouchings of the distal bile duct at the superior edge of the biliary sphincter. These lesions are most often incidental, are not associated with APBJ, and may be associated with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. These small diverticula should probably be distinguished from type II biliary cysts and have not been associated with biliary malignancy.21

Various mechanisms probably lead to formation of biliary cysts as reviewed elsewhere.22 In the majority of patients with extrahepatic cysts an APBJ is present, with elevated amylase levels in bile,11 and it is likely that chronic reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct leads to ductal dilation and biliary mucosal inflammation. Sequelae may include pancreatitis, ductal stones, biliary dysplasia, and cholangiocarcinoma. The risk of cholangiocarcinoma increases with age and may be as high as 14% in young adults23 and 50% in older adults24 presenting with symptomatic adverse events of their cysts; the prevalence of cancer in asymptomatic cysts is lower but is certainly increased compared to the general population. The risk of cholangiocarcinoma also appears to be lower in biliary cyst patients without an APBJ.9 The possibility of cholangiocarcinoma should always be considered in an adult patient with a newly diagnosed biliary cyst, especially when an APBJ is also present.

Diagnosis of a biliary cyst requires a high degree of clinical suspicion, particularly for type I cysts, which may have a similar cholangiographic appearance to a chronically obstructed bile duct. The absence of biochemical, imaging, or endoscopic evidence of obstruction is a key diagnostic finding, although patients with biliary cysts may become symptomatic only when an obstruction (due to stone or malignancy) occurs. Subtle distal bile duct obstruction may be difficult to fully exclude, and chronic narcotic or ketamine use can cause fusiform dilation of the bile duct mimicking a type IC biliary cyst,25 presumably by inducing sphincter of Oddi spasm or a subtle stricture. An APBJ, when present, is an important clue to diagnosis of an extrahepatic biliary cyst. In addition, the absence of intrahepatic ductal dilation is also a clue.

Biliary atresia is an important differential diagnosis in neonates with cystic dilations of the bile ducts. Biliary atresia generally requires surgery within 60 days of birth to prevent irreversible cirrhosis and liver failure, while biliary cysts can be safely observed through infancy and childhood. Neonates with biliary atresia have persistent jaundice, higher blood bilirubin and bile acid levels, and less impressive ductal dilation than those with biliary cysts.26

Types I, II, and IV biliary cysts are best treated with surgical resection, which manages local adverse events of the disease and decreases the risk of subsequent malignancy. Surgical drainage procedures such as side-to-side choledochojejunostomy are associated with a higher rate of subsequent benign adverse events such as recurrent biliary stones, strictures, and cholangitis as well as a persistently high cancer risk.27,28 Laparoscopic resection of types I and IV cysts appears to be safe and effective.29

Exceptions to the general principle of surgical resection include type III cysts or choledochoceles, which can be treated with endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy30 (type IIIA) or endoscopic resection (type IIIB).31 Despite the previous belief that choledochoceles are not a risk factor, cancer does uncommonly occur in type III biliary cysts.30 While resection of a biliary cyst decreases the risk of cancer, cholangiocarcinoma may occur decades after complete cyst excision.32

Patients with type V cysts (Caroli disease) typically present with pain and cholangitis due to intrahepatic stones and sludge. The management of type V cysts varies based on the distribution of cysts, stones, and strictures within the liver. Hepatic resection is often performed, sometimes in combination with endoscopic or percutaneous treatment of disease in segments of the liver that are not resected. Liver transplantation may be required.33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree