Chapter 92 PAINFUL BLADDER SYNDROME AND INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

EVOLUTION OF TERMINOLOGY: PAINFUL BLADDER SYNDROME AND INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

The last 20 years has produced and explosion of interest in the diagnosis and treatment of bladder pain. Although the attention is welcomed by patients, clinicians, and researchers alike, there is a simultaneous sense of insecurity and confusion as traditional ideas are challenged. Even the name identifying the condition, interstitial cystitis (IC), has been questioned. The original description of Hunner’s ulcers characterized a very small group of patients with a clearly defined disease defined by erythematous, bleeding areas on the bladder wall and physically diminished bladder capacity.1 In 1949, Hand2 described 223 patients, both men and women, with what would now be called IC; only 13% had severe cystoscopic findings. Nevertheless, it was left to Messing and Stamey3 to focus attention on the disorder; they described an “early diagnosis” of IC based on cystoscopic identification of glomerulations after bladder distention. This dramatically increased the population of patients considered to have IC while simultaneously raising a question as to whether these patients really had the same underlying disease. Most patients with glomerulations have normal cystoscopic findings before distention, normal bladder capacity during distention, and relatively little inflammation on bladder biopsies. Can these patients have the same condition as those with frank ulceration? In recent years, the population has been further expanded by a move to diagnose patients based on symptoms without performing bladder distention and biopsy.

The International Continence Society (ICS) proposed useful definitions to promote clarity in discussing the problem of bladder pain.4 First, it is recognized that bladder pain is part of a larger problem of genitourinary pain or pelvic pain syndromes. The document states, “The syndromes described are functional abnormalities for which a precise cause has not been defined. It is presumed that routine assessment (history taking, physical examination, and other appropriate investigations) has excluded obvious local pathologies such as those that are infective, neoplastic, metabolic or hormonal in nature.” The term painful bladder syndrome (PBS) was introduced and defined as “the complaint of suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and night-time frequency, in the absence of proven urinary infection or other obvious pathology.” It was suggested that the term interstitial cystitis be reserved for those with specific objective findings, stating that it is “a specific diagnosis and requires confirmation by typical cystoscopic and histologi-cal features. In the investigation of bladder pain it may be necessary to exclude conditions such as carcinoma in situ and endometriosis.”

Furthermore, patients with IC actually comprise at least three readily identifiable subgroups:

An important limitation of the ICS terminology is that these definitions of disease do not translate readily into entry/exclusion criteria for clinical research. Ever since the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) sponsored a conference to review the accumulated knowledge of IC in 1987, the consensus statement from this meeting5 has been considered the “official” research definition of IC. The definition encompasses inclusion criteria (Box 92-1) that describe the syndrome and exclusion criteria (Box 92-2) that serve to create a relatively homogeneous patient population. The exclusion criteria can be subdivided into two groups: first, other diseases that, if present, could engender doubt about the source of symptoms, and second, various symptoms or patient factors used to eliminate subjects that might be problematic to evaluate in a clinical trial.

Box 92-2 NIDDK Exclusion Criteria for Interstitial Cystitis Study Population

NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The NIDDK criteria were criticized in a retrospective study from the NIDDK IC Database.6 It was observed that, when patients with a wide range of symptoms were recruited for this longitudinal study, the NIDDK criteria achieved the purpose of defining a homogeneous patient population, because 90% of the database subjects meeting NIDDK criteria were believed by the experts to have IC. On the other hand, more than 60% of the patients diagnosed clinically with IC by the same experts did not meet the strict NIDDK criteria. Because use of these criteria greatly limits the available patient population and hampers clinical research; it has been argued that research trials should draw from the full spectrum of the clinical population, so that the results will be maximally generalizable.7

It has been proposed that this obstacle could be overcome by using the constellation of symptoms that defines PBS as inclusion criteria. However, at this time, there have been no published clinical trials of PBS and no published criteria for selecting patients for such trials. There is also a lack of worldwide agreement on the standard diagnostic evaluation of patients with bladder pain. In the United States, patients are often diagnosed by symptoms, and even when bladder distention is performed, biopsies are often not obtained. In Europe and other parts of the world, most patients undergo distention and biopsy, and diagnosis follows ICS terminology closely.8 Therefore, it can thus be difficult to conduct an international study. Furthermore, even when similar entry criteria are used, it may be difficult to ensure that patients from U.S. and European trials are similar, given the varying diagnostic philosophies. A recent NIDDK subcommittee charged with reviewing the literature to update the diagnostic criteria was unable find an evidence base to improve on the earlier NIDDK criteria.9 This problem may not be solved until a reliable biomarker is developed. Until such time, the NIDDK criteria will continue to be used to provide an accepted homogeneous IC population representing a subset of the affected population; this definition is appropriate for trials of more toxic treatments for those with refractory symptoms. More inclusive criteria will be proposed to facilitate additional research, particularly for the more recently diagnosed and less severely affected patients. However, the lack of universally accepted research criteria for PBS will hamper research efforts in the short term.

EPIDEMIOLOGY, ASSOCIATIONS, AND IMPACT

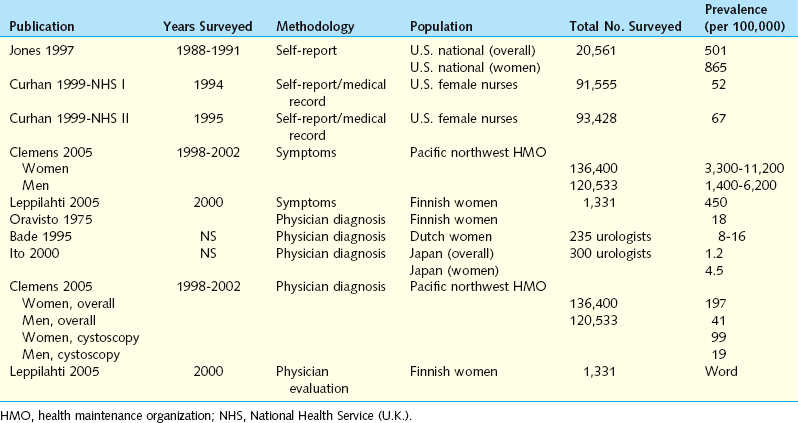

The diagnosis of IC/PBS is controversial and is based primarily on symptoms; there is as yet no objective test or marker to establish the presence of the disease, so studies to define its prevalence and incidence are difficult to conduct. Such epidemiologic studies use one of three methods: patient self-reported history, physician diagnosis, or identification of symptoms that suggest IC/PBS. The estimates of prevalence obtained vary widely, depending on when the study was performed (recognition of the disease is much greater in recent years), which methodology was used (symptoms are very prevalent, physician diagnosis relatively uncommon), and where the study was performed (physician and patient attitudes differ by culture, and there may be environmental or hereditary risk factors). The major published studies examining the incidence of IC/PBS are summarized in Table 92-1. Reports employing physician diagnoses report a much lower incidence, but the methodologies of such studies still vary considerably: some consist of surveys sent to urologists,10,11 whereas others involve review of medical records from broad, population-based samples.12,13 Each methodology has its inherent biases and limitations. Leppilahti and colleagues13 used a powerful technique in which patients were contacted from a representative population-based sample, diagnosed based on presence of symptoms, and then invited to participate in a physician evaluation to confirm the diagnosis. Even without including potential patients who could not be examined, the group estimated that the prevalence of IC in Finnish women was 230/100,000 for probable cases and 530/100,000 for possible/probable cases. The power of the study was limited by the facts that the population examined was very homogeneous and that only a small number of cases were actually diagnosed (three probable, four possible), but the results are informative and in marked contradistinction to the initial report of IC epidemiology by Orovisto,14 who found only 18 cases per 100,000 women in the same type of population. Orovisto required the presence of a confirmatory biopsy.

Two studies using self-reported histories of IC/PBS employed the same definition of disease.15,16 Participants were asked, “Have you ever had symptoms of a bladder infection (such as pain in your bladder and frequent urination) that lasted more than 3 months?” Those who answered “Yes” were then asked, “When you had this condition, were you told that you had interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome?” An affirmative answer to both questions was considered to define the presence of IC/PBS. The Curhan study15 also included review of medical records and found a much lower prevalence of disease in these records than was found by self-reported histories.

Recent studies that assess the presence of symptoms suggestive of IC/PBS provide methods of identifying undiagnosed patients. Clemens and colleagues17 used three different clinical definitions of IC/PBS symptoms in a study that included a questionnaire and review of medical records. Definition 1 consisted of self-reported pelvic pain along with urinary urgency or frequency lasting for at least 3 months. Definition 2 included the definition 1 criteria plus the presence of pain increasing as the bladder fills or pain relieved by urination. Definition 3 used results from a validated condition-specific questionnaire. Presence of IC/PBS for this definition was defined as a score of 12 or higher on the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index and Problem Index, including two or more episodes of nocturia per night and a pain score of 2 or greater. The resulting prevalence estimates were 11,200 per 100,000 women and 6,200 per 100,000 men by definition 1; 3300 and 1400, respectively, by definition 2; and 6200 and 2300, respectively, by definition 3. Interestingly, using only definition 3, a different study in Finnish women18 demonstrated a prevalence of 450 per 100,000. Finally, investigators using a very controversial approach based on the presence of symptoms and potassium sensitivity testing in a subset of patients suggested that between 10% and 30% of women in a third-year medical school class had IC and that 25 to 30 million U.S. women could be affected.19 Although this study was based on several questionable assumptions, there is no doubt that pelvic pain and lower urinary tract symptoms are exceedingly common and most likely are underappreciated in the general population. It is not yet clear that these patients actually have a unifying diagnosis. The need for an objective diagnostic marker for IC/PBS is obvious.

Only two investigators have estimated the incidence of IC/PBS. In a community-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, physician-assigned diagnoses of IC/PBS were identified using medical records from the Rochester Epidemiology Project.20 The overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate was 1.1 per 100,000 per year for the interval from 1976 to 1996. The age-adjusted incidence rates were 1.6 per 100,000 women and 0.6 per 100,000 men. The median number of episodes of care-seeking for symptoms before diagnosis was 1 for women and 4.5 for men. In this study, the cumulative incidence rate (an estimate of prevalence) was 114 per 100,000 by age 80 years. A subsequent review of physician diagnoses of IC/PBS among Kaiser Permanente Northwest enrollees identified a much higher yearly incidence: 21 per 100,000 women and 4 per 100,000 men.12 These two estimates present a rather large difference that cannot be resolved without further research. The methodologies and patient populations are quite different. It would be exciting to know that there is a substantial difference in incidence between different ethnic groups but we cannot conclude that at the present time.

Koziol and colleagues21,22 first examined the impact of IC in a population of patients treated at a single center. The found that more than 60% of the patients were unable to enjoy usual activities or were excessively fatigued, and 54% reported depression. Travel, employment, leisure activities, and sleeping were adversely affected in more than 80% of the patients. The quality of life for these IC patients (likely a very severely affected group) was worse than that of chronic dialysis patients. Another survey of 495 IC patients in the United Kingdom demonstrated similar findings.23 Sixty-seven percent of patients reported “considerable impact” or worse on their lifestyle, and 46% reported moderate depression or worse. Half of the patients reported at least considerable difficulties with sexual intercourse. There is no doubt that IC/PBS can greatly diminish quality of life in all domains (physical, social, emotional, relationships) and that the combination of chronic pain and lower urinary tract dysfunction places a burden that is matched by few other conditions.

An initial effort to determine the financial impact of IC/PBS on the U.S. healthcare system was produced from the Urologic Diseases in America project sponsored by the NIDDK. This endeavor compiled several national databases, including Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veteran’s Administration health care system, as well as private sources. The search strategy included identifying costs associated with patients diagnosed with IC (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9] code 595.1) as well attempting to identify patients who may have PBS (the combination of code 788.41 for urgency-frequency with either 625.8 or 625.9, which code for female pelvic pain). Because there is no current diagnostic code for PBS, this was the first attempt to identify such patients through coding. Among the most important findings were the following:24

Between 1992 and 2001, there was a twofold increase in the rate of hospital outpatient visits and a threefold increase in the rate of physician office visits related to IC. The annualized rate was 102 office visits per 100,000 population. The rate of ambulatory surgery visits for IC declined.

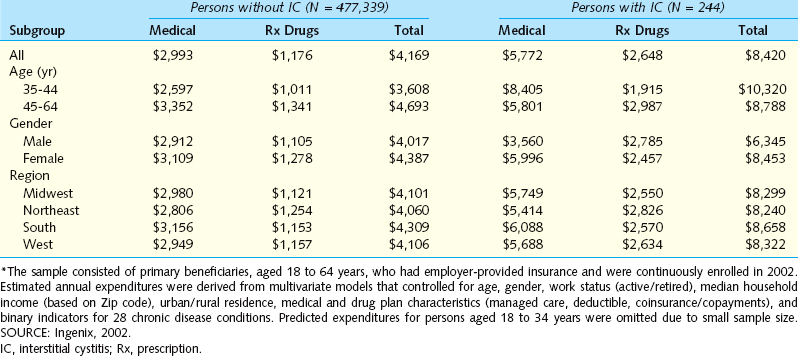

Between 1992 and 2001, there was a twofold increase in the rate of hospital outpatient visits and a threefold increase in the rate of physician office visits related to IC. The annualized rate was 102 office visits per 100,000 population. The rate of ambulatory surgery visits for IC declined. A diagnosis of IC was associated with a twofold increase in direct medical costs compared with the costs for individuals without the disorder (Table 92-2).

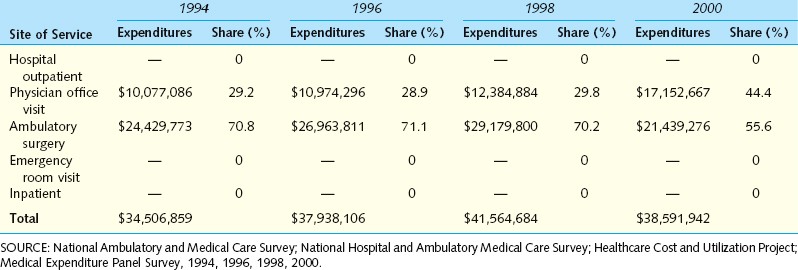

A diagnosis of IC was associated with a twofold increase in direct medical costs compared with the costs for individuals without the disorder (Table 92-2). Between 1994 and 2000, the annual national expenditure for IC was stable at approximately $37 million, but the annual costs for PBS increased from $481 million to $750 million (Table 92-3).

Between 1994 and 2000, the annual national expenditure for IC was stable at approximately $37 million, but the annual costs for PBS increased from $481 million to $750 million (Table 92-3).Table 92-2 Estimated Annual Expenditures of Privately Insured Employees with and without a Medical Claim for Interstitial Cystitis (Definition A) in 2002*

Table 92-3 U.S. Expenditures for Interstitial Cystitis (Definition A) and Share of Costs, by Site of Service

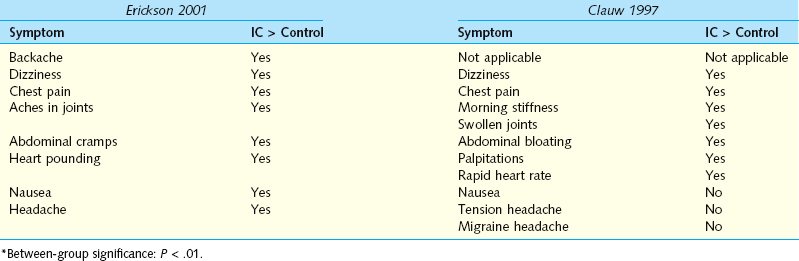

There are a number of intriguing associations with IC. Clauw25 and Erickson26 independently surveyed patients and controls for the presence of a wide variety of physical symptoms. They found striking parallels, with IC patients reporting increased cardiac, gastrointestinal, and rheumatologic symptoms, but both investigators noted that these patients with chronic pain did not simply report the presence of somatic complaints in every organ system (Table 92-4). Alagiri and colleagues27 surveyed 2405 patients with a diagnosis of IC for the presence of other diagnosed diseases plus symptoms that would suggest the presence of disease. Allergies were the most common condition, occurring at twice the rate in the general population, but more striking differences were see in dramatically increased rates of irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, Crohn’s disease, and lupus. Endometriosis, incontinence, chronic fatigue, and migraines occurred in IC patients at about the same rate as in the general public. This finding is important, because the presence of anything more than mild stress incontinence is unusual in IC/PBS patients and should prompt a more comprehensive evaluation. In contrast to this large population-based study, examination of patients in a single center showed that IC and endometriosis may frequently coexist in patients with chronic pelvic pain.28 A total of 178 female patients with chronic pelvic pain underwent both cystoscopy with bladder distention and laparoscopy. Endoscopic findings supported a diagnosis of endometriosis in 134 patients (75%), and cystoscopy confirmed a diagnosis of IC in 159 patients (89%);115 patients (65%) were diagnosed with both IC and endometriosis. The question here is whether the specific endoscopic findings are meaningful. Perhaps these patients had a generalized hypersensitivity disorder, and the glomerulations and deposits of endometriosis were not specifically related to the pathophysiology. Only more detailed research with longitudinal follow-up can answer this question.

These associated symptoms are particularly fascinating when viewed in the context of a report from Weissman and colleagues,29 who described a genetic linkage study demonstrating associations between IC and panic disorder, thyroid disorders, mitral valve prolapse, and chronic headaches/migraines. These associations parallel the increased incidence of palpitations, heart pounding, chest pain, and rapid heart rate in the reports of Clauw25 and Erickson.26 These researchers, however, did not find an increase in headaches in IC patients compared with controls. Although such a genetic syndrome would likely only involve a fraction of the typical IC patients, this discovery could ultimately produce insights about the pathophysiology of disease and lead to new medical treatments. Another view on this issue was provided by Buffington30; in his review of published associations between IC and other disorders, he pointed out that many of the associations could be explained by a common dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Buffington has carefully documented such abnormalities in a series of publications using the Feline Interstitial Cystitis model31–33 and has begun studying the response to stress in these animals. Preliminary results suggest there is dissociation between the sympathetic nervous system and HPA-axis responses to stress (see Chapter 90). This is a promising area for further research, because it could lead to improved understanding of the pathophysiology and present new avenues for treatment.

A critical question in defining the future of IC/PBS and other pelvic pain syndromes is whether there are meaningful distinctions between different syndromes. Wessely and colleagues34 performed a literature review in 1999; they found that a substantial overlap existed between the individual syndromes and that the similarities between them outweighed the differences. Similarities were apparent in case definition, reported symptoms, and nonsymptom associations such as gender, outlook, and response to treatment. They concluded that the existing definitions of these syndromes in terms of specific symptoms were of limited value and proposed that a dimensional classification would probably be more productive. They further postulated that the existence of specific somatic syndromes is largely an artifact of medical specialization; that is to say, the differentiation of specific functional syndromes reflects the tendency of specialists to focus on only those symptoms pertinent to their specialty, rather than any real differences among patients. There may be no more important question than this. For both research and treatment, it is critical to determine whether IC/PBS is really a primary disease of the bladder or part of a larger predisposition to chronic pain.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The name “interstitial cystitis” implies a chronic bladder inflammation, and most of the theories about the pathophysiology of this disorder involve inflammation. Abnormally increased numbers of detrusor mast cells and/or abnormal mast cell function35,36 have been suggested to be key features of the disease. The hypothesis is attractive because of the symptoms of the disease and the association with allergies and food sensitivities. However, although ulcer patients clearly have classic chronic inflammation on biopsy, the majority of subjects in the NIDDK Interstitial Cystitis Database study did not have significant histologic inflammation.37 Moreover, treatment with mast cell inhibitors has been largely disappointing, and urinary histamine and its metabolites have not been reliable markers for the disease.38

For many years, the primary theory of IC pathogenesis was a deficiency in the protective glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer of the bladder. Parsons and others suggested that GAGs are quantitatively and qualitatively diminished. A unifying theory of urologic pelvic pain centered on epithelial cell dysfunction was proposed by Parsons.39 The concept is that the defective urothelial barrier allows potassium and other solutes to diffuse back into the bladder, stimulating pain nerves and creating local inflammation. IC patients are clearly more sensitive to intravesical potassium (see later discussion), but actually proof of abnormal bladder permeability has been elusive. In addition, treatment aimed at restoring the GAG layer has been relatively disappointing. The clinical or basic science breakthrough that would substantiate this attractive theory has yet to arise.

The most promising scientific research in IC involves antiproliferative factor (APF). The presence of a substance in the urine of IC patients that inhibits urothelial cell growth in culture (but is not cytotoxic) was first described in 1996 by Keay and colleagues.40 Subsequent work from the same group demonstrated that APF was found in bladder urine but not in urine taken from the renal collecting system,41 that it was found in almost all IC patients but rarely in normal controls or in patients with other urologic disorders,42 and that abnormally high levels of APF reverted to normal after patients were treated by bladder distention and sacral nerve stimulation.43,44 APF activity also has been shown to correlate with other known epithelial growth factors EGF and HB-EGF.45 The structure of APF was finally elucidated in 2004 by Keay and colleagues46; it belongs to the family of frizzled 8–related sialoglycopeptides and has 100% homology to the sixth transmembrane segment of the G protein–coupled Wnt ligand receptor. At this time, there is no easy test to assess APF, because the assay still depends on a cell culture. If an antibody-based assay can be developed in the future, it could have a major impact on the diagnosis of IC/PBS. This in turn would greatly facilitate both clinical and epidemiologic research. The ultimate question is whether APF is a simply a marker associated with the disease or is integrally involved in its pathophysiology.

Warren and colleagues have investigated the possibility that susceptibility to IC is inherited. One study involved a pilot mail-in study of members of the Interstitial Cystitis Association.47 The participants were asked about the presence of IC symptoms and a diagnosis of IC in all first-degree relatives. Diagnosis was not confirmed in the probands or relatives. The survey found that women, aged 31 to 73 years, who were first-degree relatives of patients with IC, themselves had a prevalence of IC of 995/100,000. This suggests a relative risk of up to 17 times that in the general population, based on Curhan’s study of IC prevalence.15 This team also investigated IC in twins. Of the co-twins of 8 monozygotic twin respondents, 2 had probable and 3 had confirmed IC, compared with none of the co-twins of the 26 dizygotic twin respondents (including 15 female co-twins). Although this is a very small sample, the striking results suggest that there may be a genetic susceptibility to IC.48

CURRENT DIAGNOSTIC TESTS AND STRATEGIES

As discussed earlier, the 1988 NIDDK research criteria are the product of “expert opinion” and were intended to ensure that the populations in research studies would be comparable. The criteria were not intended for clinical practice; even in the research setting, they function suboptimally by excluding too many appropriate subjects. Because of this controversy, the NIDDK charged a subcommittee to examine the evidence supporting current diagnostic strategies and knowledge and identify the gaps to be filled. This was intended to be the first step in moving toward an evidence-based definition of IC and to include specific recommendations for future research that would create the necessary evidence. Individual participants reviewed the published data on urodynamics, biomarkers, potassium sensitivity testing, cystoscopy with distention and biopsy, and questionnaires. The conclusions of each reviewer were discussed and modified by the whole subcommittee. Each author then presented the conclusions for public comment at the 2003 NIDDK Interstitial Cystitis Research Symposium on November 1, 2003, in Alexandria, Virginia. This meeting was attended by more than 250 international experts in IC, including clinicians from many different specialties and basic science researchers. The subcommittee found that, in the 15 years since publication of the original NIDDK guidelines, no high-quality evidence had been developed to support the routine use of any diagnostic test in defining IC. The specific findings and recommendations are included in the following sections.

Urodynamics

Urodynamic studies are required to diagnose IC by the NIDDK entry criteria. Despite this fact and the many papers that purport to study IC based on the NIDDK criteria, the reviewers in 2003 identified only 10 papers that described urodynamic findings. The NIDDK criteria include the presence of noncompliant filling as a positive factor in the diagnosis and the presence of involuntary detrusor contractions (IDCs) as an exclusionary factor. However, although diminished compliance appears to occur in a subset of patients with IC/PBS, this feature of the disease has not been characterized sufficiently to be of any clinical value. At the same time, IDCs are consistently reported in a subset of IC/PBS patients and correlate with symptom severity. No data were found to suggest that these patients are different from patients who do not have IDCs. It was concluded that IDCs should not be used to exclude a diagnosis of IC/PBS. One important point presented was that most of the reports did not include any assessment of pain during bladder filling and that the standard urodynamic terms of “first desire to void” and “urgency” may not be adequate to describe urodynamics in patients with IC/PBS.49

My colleagues and I use urodynamic testing selectively, with the primary indications being the presence of significant incontinence, prominent voiding difficulty or high residual urine, and failure to respond to treatment. The test is adapted from the technique described by Teichman and colleagues.50 We typically perform a baseline filling/voiding cystometrogram. This is followed by a potassium sensitivity test (PST) as described by Parsons.51 The bladder is then anesthetized with alkalinized lidocaine, as described by Henry,52 and cystometry is repeated. It is important that voiding be adequately evaluated before the PST and lidocaine instillation, because there is a significant incidence of voiding abnormalities, much of it related to pelvic floor dysfunction, and this may offer a separate avenue for therapy (see later discussion of pelvic floor therapy).

Cystoscopy with Bladder Distention and Biopsy

More than 50 papers including data on cystoscopy, bladder distention, and bladder biopsy were reviewed.53 Although the presence of glomerulations after bladder distention has long been considered to be the sine qua non of IC, there is no body of evidence to support this hypothesis. The sensitivity of glomerulations as a marker for IC was questioned by Awad and colleagues.54 This group defined patients with subjective symptoms of IC and supportive urodynamic findings. They found no difference between those who did and did not have glomerulations after bladder distention in histology or in response to treatment. The specificity of glomerulations was questioned by Waxman and associates.55 They photographed bladder distentions performed on asymptomatic women presenting for elective tubal ligation. The photographs were reviewed by outside experts along with similar photographs taken from distentions of IC patients. The study conclusively demonstrated that the bladder mucosal lesions characteristically associated with irritative voiding symptoms and pelvic pain in patients diagnosed with IC were also observed in asymptomatic women. More recently, Erickson and colleagues56 prospectively evaluated 36 patients undergoing bladder distention using the NIDDK cystoscopic criteria. They found no difference in symptoms or in response to the procedure between those who did and did not meet cystoscopic criteria for IC. There was no difference in histology or urine markers. They concluded that, “cystoscopic criteria do not appear to identify a distinct pathophysiologic subset of patients with IC symptoms.”

It would thus appear that cystoscopy under anesthesia with bladder distention cannot be recommended as a mandatory test. At the same time, patients with chronic disease are often concerned about cancer and crave more information about their disease. Either the patient or the clinician may feel a need for further evaluation. IC does not appear to predispose patients to bladder cancer. On the other hand, several authors have published cases series of patients who were misdiagnosed with either IC or chronic pelvic pain and actually had bladder cancer or carcinoma in situ.57–59 This is of great concern because of the trend away from examining all patients with cystoscopy. It is certainly important to maintain a high index of suspicion in these patients and to use diagnostic studies such as cystoscopy and cytology prudently. In selected patients, office cystoscopy can be well tolerated and can provide the necessary information to exclude other diseases (although the bladder can rarely be distended enough to produce glomerulations without severe pain in the absence of anesthesia). If cystoscopy is performed under anesthesia, abnormal or suspicious areas should certainly be biopsied, but there is as yet no evidence that routine biopsies of normal areas or glomerulations provide useful diagnostic or therapeutic information. At the present time, it seems rational to conclude that cystoscopy should still be used for patients with PBS and microscopic hematuria or pyuria, risk factors for bladder cancer, and for those patients for whom empiric therapy has failed. Two investigators have suggested that the likelihood of identifying any specific cause for microscopic hematuria in young women with PBS is very low.60,61 Perhaps such low-risk patients might be initially evaluated with ultrasonography and cytology.

Biomarkers

APF was discussed in detail earlier. Currently, there is no clinically useful biomarker for IC/PBS. There is a need for large, multicenter prospective studies, including a broad spectrum of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic pain, in which APF (and other putative biomarkers) can be tested on all patients at enrollment and correlated with eventual diagnosis and response to therapy.

Potassium Sensitivity Testing

The most controversial tool in the IC/PBS diagnostic armamentarium is the PST. First described by Parsons,51,62 the PST has been studied more extensively than any other test. In this test, 50 mL of sterile water and 50 mL of 0.4N KCl are instilled into the patient’s bladder sequentially, and the patient is asked to rate the degree of pain and urgency on a scale of 0 to 5. An increase of 2 points in either symptom is considered a positive test. It should be noted that the PST assesses sensitivity to intravesical instillation of potassium. The concentration used is pharmacologic, not physiologic. A positive test may indicate increased permeability of the urothelium to potassium, increased sensitivity of the bladder nerves, or some combination of the two.

Many investigators using very different patient populations have unanimously concluded that this test separates IC patients from normal subjects. The question is whether the test meaningfully separates patients with IC/PBS from those with other diseases. Reports document high rates of positive testing in patients with prostatitis, urethral syndrome, and a wide variety of gynecologic disorders, as well as a substantial minority of patients with detrusor overactivity (Table 92-5).63–65 As discussed earlier, Parsons39 has proposed that the test accurately identifies a large group of patients with undiagnosed IC/PBS who share a common uroepithelial dysfunction. Another explanation for the wide positivity of the test is the concept of neural cross-sensitization and referred pain. FitzGerald and colleagues66,67

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree