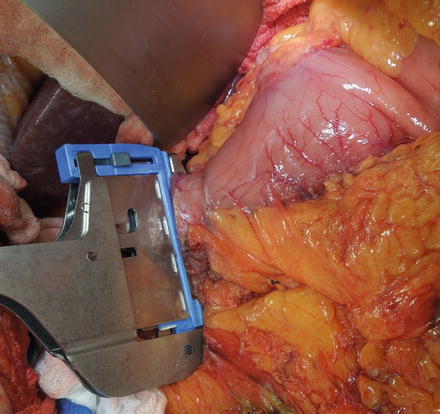

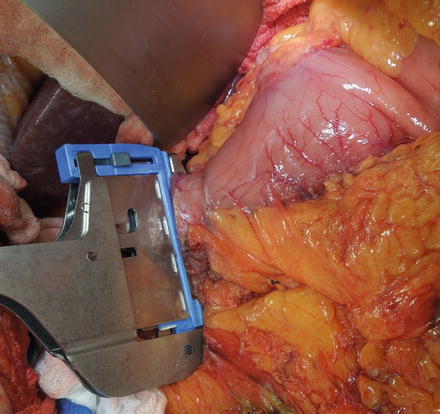

Fig. 6.1

Operating room setup

Expose the anterior surface of the pancreas and delineate the superior pancreatic margin until the right gastroepiploic vessels are identified as shown in Fig. 6.2. The vessels should be individually clamped, divided, and ligated close to the gastroduodenal artery. Next, we mobilize the left hepatic lobe by dividing the triangular ligament and taking care to avoid injury of the left phrenic vein. Once the left lateral segment is retracted the lesser omentum will be visualized. We perform lesser omentectomy by removing all the tissue along the lesser curvature from the inferior edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament to the right crus of the diaphragm. The right gastric artery and vein are identified, clamped, transected, and ligated close to the takeoff from the hepatic artery (Fig. 6.3).

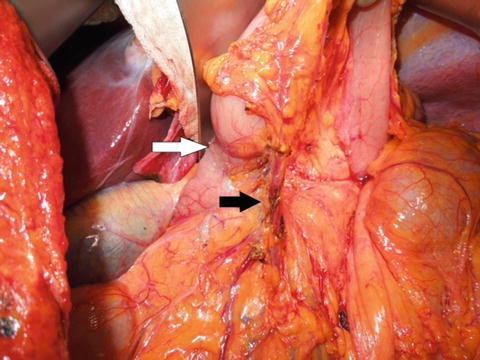

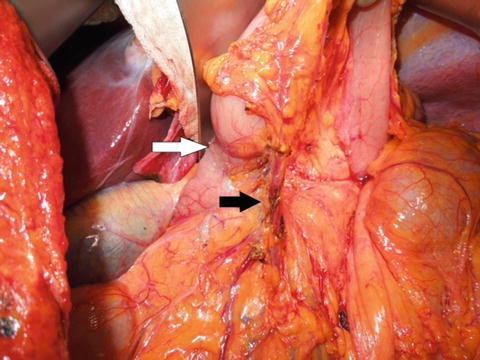

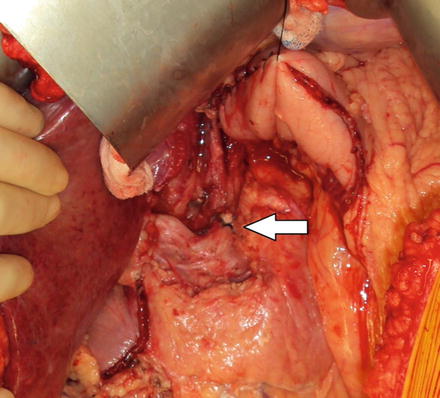

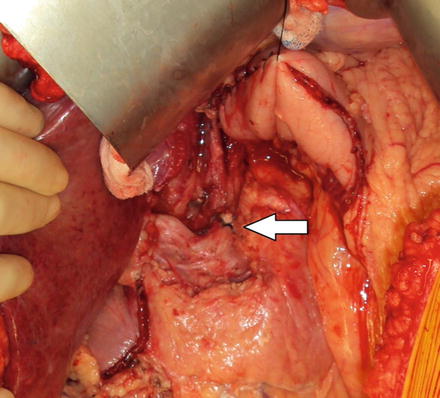

Fig. 6.2

Right gastroepiploic vessel dissection. The white arrow indicates the location of the pylorus and the black arrow indicates the gastroepiploic vessels

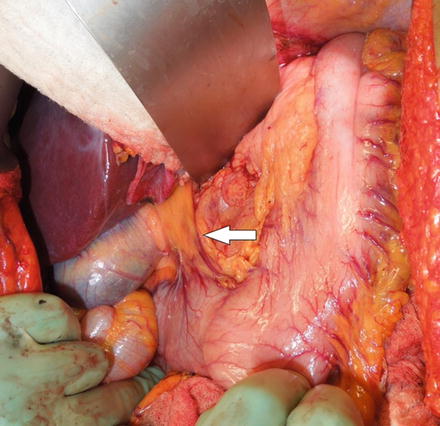

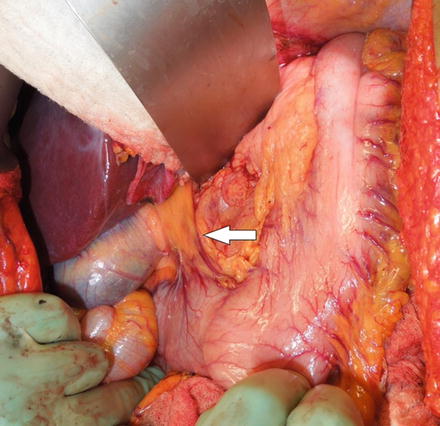

Fig. 6.3

Right gastric vessels prior to dissection. The white arrow indicates the location for dissection of the right gastric vessels

We palpate the gastroduodenal junction to assess tumor involvement. If no tumor is present, then the duodenum is divided approximately 2 cm from the pylorus. When the tumor involves the duodenal bulb, care must be taken not to compromise the ampulla of Vater, the common bile duct or the minor papilla. We prefer using a thoracoabdominal (TA) or gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler to transect the duodenum as shown in Fig. 6.4. With the duodenum divided, exposure of the nodal tissues along the hepatic artery, celiac axis, and splenic artery is enhanced. We continue our dissection along the superior border of the pancreas taking all the nodal tissues along the common hepatic artery towards the celiac axis. Identify the left gastric vessels and ligate them at their origin (Fig. 6.5). The nodal tissues around the left gastric artery should be removed with the specimen. We identify the splenic artery near its origin and dissect towards the splenic hilum, removing all the nodal tissues with the specimen. The extent of D1 lymphadenectomy for distal gastrectomy includes stations 1, 3, 4 (excluding station 4 nodes along the short gastric vessels which are preserved), 5, 6, and 7; while D2 lymphadenectomy includes the D1 stations along with stations 8, 9, 11, and 12.

Fig. 6.4

The image shows the duodenum being divided by a TA stapling device

Fig. 6.5

D2 lymph node dissection with left gastric vessel ligation. The white arrow indicates the celiac trunk with suture ligation of the left gastric artery

The greater omentum is removed from the greater curvature of the stomach taking care to preserve the proximal short gastric arteries that will supply the remnant stomach. A location on the stomach, proximal to the tumor, is identified with the goal of a 5–6 cm margin that is grossly free of tumor. The stomach is divided at this point using a GIA stapler. Frozen section assessment of the surgical margins should be performed to confirm histologically negative margins.

Reconstruction with Roux-en-Y Gastrojejunostomy

Several reconstructive methods have been described after distal gastrectomy. Our preferred approach is retrocolic Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. Another commonly used method is Billroth II anastomosis. Both methods are briefly described below.

For reconstruction with Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, the jejunum is divided approximately 20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. The transverse colon is retracted up and out of the wound and an avascular window in the mesocolon is identified. A small 4-cm incision is made in the avascular area to the left of the middle colic vessels. The Roux limb is then delivered through the created defect so that the jejunum abuts the gastric remnant without tension. Although the gastrojejunostomy can be either stapled or hand-sewn, we prefer a hand-sewn two-layer anastomosis. The posterior serosal layer is made by placing seromuscular interrupted 3–0 silk sutures in Lembert fashion approximately 5 mm apart, affixing a 4-cm segment of jejunum to the posterior gastric wall. The two corner sutures are tagged with hemostats and used for traction while creating the anastomosis. The remaining silk sutures should be cut. Next, a 4-cm segment of the gastric staple line is removed close to the greater curvature. A similar defect approximately two-thirds the size of the gastric opening is made in the anti-mesenteric wall of the jejunum using electrocautery. The mucosal layer of the anastomosis is created using 3–0 absorbable sutures in a running fashion taking care to incorporate the full thickness of each wall. This inner layer is created by starting in the middle of the posterior mucosal wall and running the suture in both directions until they meet at the anterior surface to create a circumferential watertight anastomosis. A Connell technique can be used starting at each turning corner to ensure that the mucosa is inverted. Finally, an anterior serosal layer of 3–0 silk sutures with seromuscular bites taken in Lembert fashion imbricates the anterior mucosal layer and completes the anastomosis. To prevent internal hernias, the wall of the Roux limb is secured to the mesocolon at its point of entry into the retrocolic space and any remaining defect can be closed. A jejunojejunostomy is then created using the same two-layered hand-sewn technique described above. The proximal jejunum is anastomosed to the Roux limb approximately 60 cm from the gastrojejunostomy. Again, the mesenteric defects of the jejunal limbs are closed by reapproximating the cut edges of the mesentery.

Reconstruction with Billroth II Gastrojejunostomy

Again our method of choice for a retrocolic Billroth II reconstruction is a two-layered hand-sewn anastomosis. A loop of jejunum is brought up through the created window in the avascular portion of the transverse mesocolon so that the gastric remnant is approximately 20 cm from the ligament of Treitz. A hand-sewn gastrojejunostomy can be created using the techniques described above for Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. We do not advocate the routine placement of drains unless there is concern for possible pancreatic leak or injury. If necessary a 19-French Blake drain is exteriorized through a separate incision.

Postoperative Management

Day of surgery: Deep breathing exercises and aggressive pulmonary toilet are initiated.

Postoperative day #1: Early ambulation is started. Intravenous fluids are changed to maintenance rate if the patient is euvolemic.

Postoperative day #2: The nasogastric tube is discontinued. The patient remains nil per os (NPO). The sterile dressing is removed. Tube feedings are initiated if a jejunostomy tube was placed at the time of surgery. We recommend starting at a low rate of 10–20 mL/h and slowly increasing as tolerated over the next few days or once the patient has return of bowel function. Careful attention should be paid to complaints of abdominal cramping and/or distention.

Postoperative day #3: The patient is started on a clear liquid diet.

Postoperative day #4: The diet is advanced over the next 24–48 h to a postgastrectomy diet. Once tolerating full liquid or postgastrectomy diet, transition to oral medications is completed and intravenous fluids are discontinued.

Postoperative day #5–6: The morning dose of heparin is held and the epidural is discontinued. The urinary catheter is discontinued 6 h later.

The patient meets criteria for discharge when: (1) ambulating, (2) pain is controlled on oral pain medications, and (3) tolerating postgastrectomy diet while meeting caloric goals by eating or by supplemental enteral feeds.

If a drainage catheter was placed at the time of surgery, a serum and drain amylase concentration should be obtained once the patient is tolerating a diet. If the output is non-bilious and there is no chemical evidence of pancreatic leak (drain amylase <3× serum amylase), then the drain can be removed.

Complications

Early Postoperative Complications

The most frequent complications encountered after distal gastrectomy are those seen in any patient undergoing major abdominal surgery. These include postoperative bleeding, wound infection, pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, and urinary tract infection. Complications specific to distal gastrectomy include delayed gastric emptying, duodenal stump leak, gastrojejunostomy leak/obstruction, and jejunojejunal anastomotic leak/obstruction. Anastomotic leaks are associated with a high morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. The key to management is early diagnosis and intervention. Symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, distention, tachycardia, and laboratory abnormalities such as leukocytosis or acidosis. Most anastomotic leaks can be managed nonoperatively. However, duodenal stump leaks often require surgical intervention.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree