Chapter 40 MIDURETHRAL TO DISTAL URETHRAL SLINGS

MIDURETHRAL TO DISTAL URETHRAL SLINGS

Short History of Midurethral Slings

The first prototype midurethral sling, the “intravaginal slingplasty” operation, was performed in 1986. This operation1,2 was based on the anatomic work of Robert Zacharin3 and the observation that an implanted plastic fiber causes a controlled deposition of collagen. It was reasoned that a tape placed at the site of the pubourethral ligament, without tension, would create a scar tissue reaction and strengthen the weakened ligament. It was also reasoned that a midurethral tape placement without abdominal attachment would eliminate most of the postoperative pain and urinary retention associated with sling and colposuspension procedures. These hypotheses were proven in the prototype intravaginal slingplasty operations. The one remaining problem, a high rate of foreign body reaction to Mersilene, was resolved by using polypropylene.2

Structural Anatomy

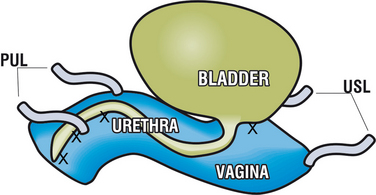

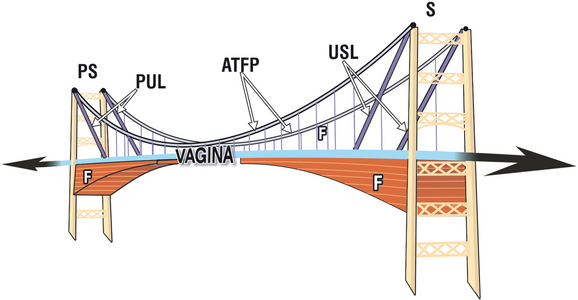

Without ligamentous support, the bladder, urethra, and vagina have no shape, strength, or function. Fibroligamentous attachments connect urethra and bladder base to the vaginal membrane (Fig. 40-1), so any laxity of the underlying vagina may influence the urethra and bladder base. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a mechanical process.1 To better understand the pathogenesis and treatment of SUI, it is useful to examine how ligaments, fascia, and muscle forces all combine to give shape, strength, and function to the vagina. All the component structures in Figure 40-2 are interconnected, and all have a role in the functioning of the system. It follows that more than one damaged structure may need to be repaired for optimal restoration of a particular function.

Anatomy of the Urethra’s Attachments

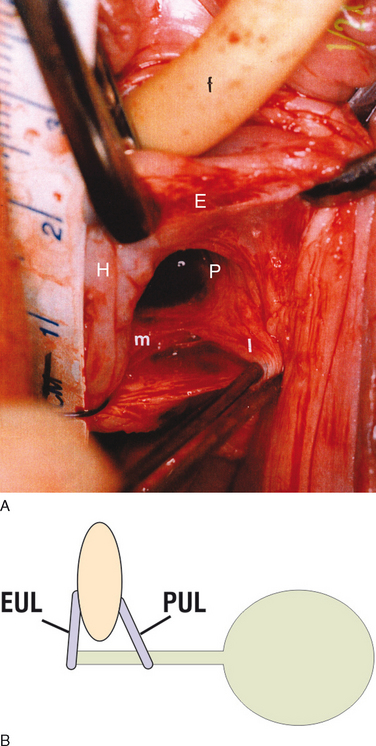

Figure 40-3 is a live anatomic study4 of the structures involved in urethral closure. They are, in order of importance, the pubourethral ligament (P), the suburethral vaginal hammock (H), and the external urethral ligaments (E). The external ligament E attaches the external urethral meatus to the anterior surface of the pubic bone. The pubourethral ligament P descends from the posterior surface of the pubic bone.3 Its medial part (m) attaches to the middle part of the urethra, and its lateral part (l) to the pubococcygeus muscle and, by extension, to the vagina.

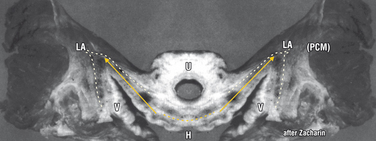

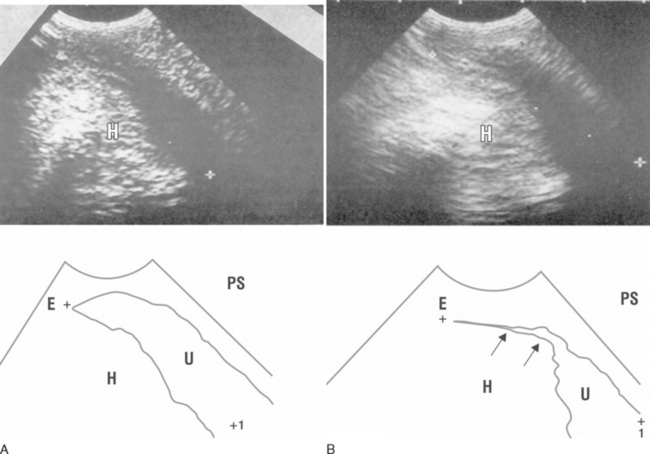

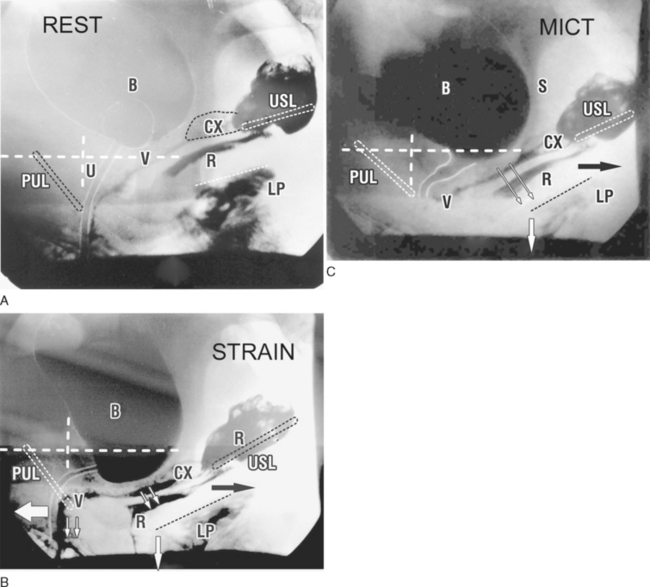

In 1963, Robert Zacharin demonstrated that the vaginal hammock is inserted into the lateral closure muscles (Fig. 40-4). This anatomy is consistent with dynamic video radiographic studies and ultrasound observations (Figs. 40-5 and 40-6).

Dynamic Anatomy of Urethral Closure

Abdominal ultrasound5 (see Fig. 40-5B) demonstrates the contribution of the hammock and external ligament (E) to urethral closure. Closure occurs from behind, presumably by forward stretching of the hammock (H) against (E) by contraction of the pubococcygeus muscle (PCM).

Importance of Midurethral Anchoring for Closure and Micturition

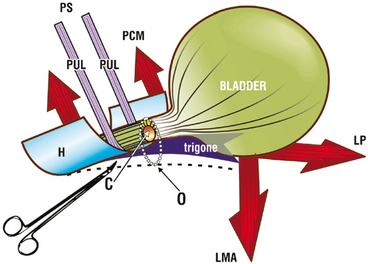

The importance of a midurethral anchoring point is evident on the sequence of radiographs in Figure 40-6. During straining (see Fig. 40-6B, arrow), the distal urethra is pulled forward against the pubourethral ligament (PUL) for “urethral closure.”1 The proximal urethra is stretched backward and downward against the PUL (arrows) for “bladder neck closure.”1 During micturition (see Fig. 40-6C, arrows), the forward muscle force appears to relax, allowing the posterior urethral wall to be pulled open by the backward/downward muscle forces, right down to the PUL anchoring point. This opening vastly reduces the intraurethral resistance, facilitating the expulsion of urine. A surgical attachment at the bladder neck (Burch, fascial sling) may forcibly restrain the urethra from being stretched open during micturition, so that the detrusor has to expel urine through a narrower channel with a much higher resistance. The patient perceives this symptomatically as a slow flow, stopping and starting, incomplete emptying, and so on. From these radiographs it can be deduced that, whatever the operation performed for SUI, anchoring at or near the mid-urethra without excessive tension is an important factor in preventing postoperative urinary retention.

Clinical Anatomy: “Simulated Operations”

The individual contribution of the PUL, hammock, and the external urethral ligament (EUL) to urethral closure can be demonstrated directly by the office technique of “simulated operations.” This technique also directly tests the theory underlying this work1 for truth or falsity. A patient with known urine loss on coughing is tested with a full bladder in the supine position.7 Pressing upward on the anterior vaginal wall at the level of mid-urethra with a hemostat during coughing (Fig. 40-7) provides a temporary anchoring mechanism and mimics a midurethral sling. This maneuver immediately reduces urine loss in approximately 70% to 80% of patients.7 Taking a fold of the hammock with a second hemostat (“pinch test”)8 usually restores complete continence in the remaining 20% to 30% of patients.7 Anchoring the external urethral meatus may decrease urine loss in approximately 10% of patients. The synergistic actions of these structures can be demonstrated by anchoring one and then two structures simultaneously.

Anatomic Basis for Simulated Operations

During closure, the backward muscle forces (see Fig. 40-7, arrows) stretch the vaginal membrane and the trigone backward against the PUL. This action tensions the urethral tube and the vaginal hammock.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree