Chapter 55 IMAGING IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

Pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor relaxation are two related and often coexistent conditions. Prolapse refers to an abnormal and noticeable protrusion of bladder, urethra, vagina, or rectum through fascial and hiatal defects typically involving the perineum. Pelvic floor relaxation, which typically accompanies prolapse, refers to a weakening of the suspensory fascia, ligaments, and muscles of the pelvic sling. Patients typically do not present with an isolated organ defect; instead, these often complex disorders typically comprise a combination of abnormalities such as a rectocele, an enterocele, or a cystocele. These disorders often occur in middle-aged to elderly women. Symptoms may include urinary incontinence, pain, pressure, perineal herniation, and bulging. On physical examination, findings are often equivocal, because the pelvic anatomy may be distorted due to prior pelvic surgery or severe abnormalities. Clinicians rely on a combination of imaging modalities and functional testing (e.g., urodynamics, anorectal manometry) to help describe the anatomic and functional defects.1,2 Currently, both fluoroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are widely used and complementary techniques to evaluate disorders of the bladder, vagina, and rectum.3

IMAGING MODALITIES FOR EVALUATION OF PELVIC FLOOR DISORDERS

Fluoroscopy

Fluoroscopic evaluation of either voiding or defecation may be performed with the patient in the upright position after opacification with contrast material (Fig. 55-1). Some believe that the upright position most closely resembles the physiologic condition reproducing symptoms, and it has been used as a natural extension of the physical examination.4 Disorders of the posterior pelvic compartment, which typically include constipation and incomplete defecation, may be studied by instilling a barium paste into the rectum and performing a dynamic fluoroscopic evacuation proctogram or defecogram. Similarly, the bladder may be instilled with a water-soluble iodinated contrast agent during dynamic evaluation of filling and voiding by the traditional voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). Also, the vagina may be similarly studied by dynamic vaginography.5 With the “four-contrast” defecogram (in which the bowel, rectum, vagina, and bladder are opacified), the relationships among these compartments may be studied simultaneously.1

Defecography

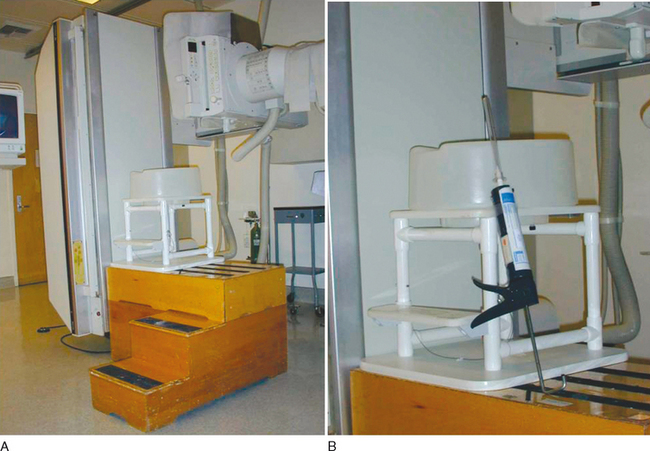

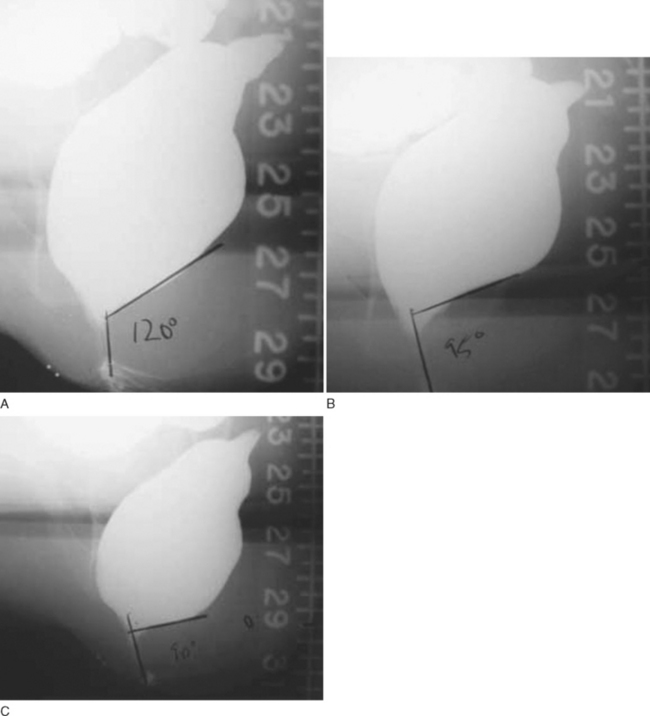

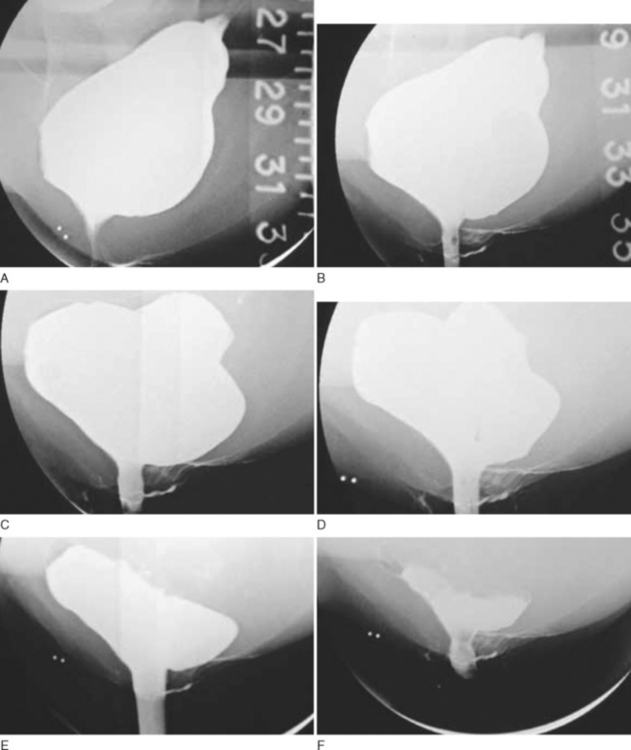

Defecography, or evacuation proctography, is a simple radiologic technique that is used to image the rectal voiding process of a barium-based paste enema. During the examination, the patient sits on a special defecography radiolucent commode while fluoroscopic images are recorded in the lateral projection. Although exact protocols vary, in general, one obtains views at rest, at maximal contraction of the voluntary anal sphincter and pelvic floor musculature without actual defecation, while coughing, while emptying the rectum as completely as possible, and while straining maximally after the evacuation is complete (Figs. 55-2 and 55-3).5 In addition to using barium-based enemas, many urogenital imagers also administer an oral barium suspension with Gastrografin 30 to 60 minutes before the examination to opacify the bowel and thus facilitate the identification of enteroceles. One can also use contrast gel injected into the vaginal apex and look for rectovaginal separation on the images as an indication of an enterocele.6 The recording process varies from obtaining spot films to videotaping the entire process during so-called dynamic proctography.

The most essential part of the examination is the assessment of evacuation rate and completeness.7 Defecography yields both morphologic and functional information, because it provides imaging of the rectal configuration throughout all of the phases of evacuation and allows assessment of whether the latter process is normal or prolonged.6 Such factors of pelvic floor function as rectal emptying and volume, anal sphincter competency, and perineal and pelvic floor musculature can be evaluated with this technique. It is possible to identify the prolapsed organs, to evaluate the morphology of the bladder neck, and to identify the axis of the bladder and the vagina. However, defecography does not assess fine mucosal abnormalities.6

There is an important caveat that pertains to the interpretation of defecographic findings by clinicians. Given that there is a rather wide overlap between standard defecographic measurements and findings among normal asymptomatic patients and those with significant symptomatology, radiographic findings obtained during defecography are not to be used as reliable diagnostic criteria of pelvic floor abnormalities.8–10 They must be combined with clinical measurements and subjective symptoms reported by the patient for interpretation. Many experts agree that defecography alone is of limited value in clinical decision-making and should be interpreted with the results of complementary testing such as anorectal manometry and pelvic MRI.6

Colpocystodefecography

Colpocystodefectography (CCD) or dynamic cystoproctography (DCP) combines voiding cystography, vaginal opacification, and defecography (discussed in the previous section). The imaging study itself is very similar to that described for defecography. The patient is either upright or seated in a special defecography stool-chair, depending on the phase of the examination, with the images being taken during the static and the dynamic phases of the examination. During the former phase, the patient is either resting, performing a Valsalva maneuver, or maximally contracting her anal sphincter; the latter phase of the study involves micturition and defecation.11 Therefore, information obtained during a single CCD study is a combination of voiding cystography and defecography.

CCD has been shown to be more sensitive than physical examination in the detection of various forms of female pelvic organ prolapse, and it was developed to complement the physical examination.12 It has the advantage of examining the patient under the force of gravity in either upright or seated position, thus revealing pelvic floor weakness during physiologic activities as well as rest. However, it does include exposure of the patient to the effects of ionizing radiation, and it puts a time-constraint on both the examiner and the examinee. In addition, it is a rather intrusive technique and requires a great deal of cooperation from the patient as well as patience from the examiner.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is popular because it is an inexpensive, noninvasive imaging technique that does not involve the use of ionizing radiation. It is currently best reserved for evaluation of pelvic organs and bladder volume. The main disadvantages of this technique are its operator dependence and suboptimal ability for comprehensive visualization of tissue planes.5 Because of these drawbacks, pelvic floor prolapse has been graded by physical examination far more often than by either transvaginal, transrectal, or transperineal ultrasound.4

Endoanal Approach

Endoanal ultrasound is used to assess the anorectal junction in patients with incontinence, because other approaches such as abdominal, perineal, or transvaginal scanning are not capable of visualizing the anal sphincter muscles as adequately as the endoanal approach.13 Although the anal sphincter and even, to a certain extent, upper anal canal defects can be visualized, there is a very wide range of normal findings owing to differences in methodology and reproducibility of measurements with fibers that lie oblique to the plane of the imaging probe.5 Positioning of the patient is also important and somewhat gender specific. Whereas in men the left lateral position is adequate, female patients should be imaged either prone or in lithotomy position so as to not disturb the anterior anatomy and to increase the diagnostic accuracy of the study.14 In general, series of images are taken at several levels of depth as the probe is being withdrawn from the anal canal, with detailed examination of any abnormality encountered along the way.

Transvaginal Approach

Female anatomy is unique in that it allows a transvaginal approach to imaging of anal sphincter abnormalities. It is possible to obtain a unique view of the sphincter in its closed state during this study when the probe placed in the distal vagina/perineum is angled backward. Perineal body thickness, the subepithelial thickness, anal cushions, and sphincter damage can be assessed.15 However, even though the transvaginal approach allows for assessment of the anal sphincters, the endoanal approach is superior for defining the extent of sphincter tears and confirming their intactness throughout their length.13,15 In addition to assessing the anal sphincter, transvaginal sonography allows assessment of the urethra and bladder in supine or sitting positions as well as during dynamic studies in the assessment of urinary continence mechanisms.16 In some cases of enteroceles, it is possible to visualize bowel loops extending down into the rectovaginal space during this examination.17

Perineal Approach

In the perineal approach, the pelvic floor is imaged while the ultrasound probe is placed on the perineum. It is also possible to obtain good images of the bladder neck and pubic symphysis at rest and during Valsalva maneuvers in the sagittal plane with the probe placed over the vulva. Although the relationship of dynamic transperineal ultrasound to other, more established imaging modalities remains to be fully assessed, it has a great potential as a simple, cheap, and relatively noninvasive technique. With the perineal approach the position of the bladder neck, the pubo-rectalis, and the anorectal angle can be measured. In addition, during straining phases, it is sometimes possible to visualize rectoceles, cystoceles, enteroceles, and rectal intussusceptions.15 Some investigators recommend using rectal and vaginal opacification with ultrasound coupling gel during dynamic transperineal ultrasound studies. With the patient in the left lateral position and a full bladder, movement of the pelvic floor muscles is observed in the sagittal and coronal planes during straining and squeezing.18

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI offers a myriad of advantages over other imaging modalities: lack of ionizing radiation, ease of performance, reproducibility, excellent depiction of pelvic floor soft tissues, multiplanar imaging, and, perhaps most important, its dynamic rapid acquisition capabilities.19–23 Because MRI is capable of superior differentiation between soft tissues and fluid-filled viscera, the musculofascial support structures of the pelvic organs can be visualized.24 By using different imaging systems, it is possible to tailor the imaging examination to the needs of the patient and the clinician. Whereas endoanal coils yield the highest-resolution images of the anal sphincter, with somewhat limited visualization of other pelvic floor structures, a body coil permits greater flexibility during the examination, because it results in a more global view of the perineum and the pelvic floor.5 In addition, most cases of pelvic floor dysfunction involve several pelvic compartments, and MRI is an invaluable technique because it is ideally suited for simultaneous multicompartmental anatomic assessment during a given imaging study.2,25

The patient’s prone position inside the magnet during the study is the only obvious disadvantage of using MRI, because it naturally eliminates the gravity component from the pelvic prolapse, which may be more pronounced while standing or sitting.26 However, practically speaking, most clinical physical examinations by urologists and gynecologists are performed with the patient in the prone position. In addition, at least one study designed to compare MRI findings in the upright and supine positions found no significant differences, although the small sample size of this study could have contributed to the statistical insignificance reported by the authors.25,27 More important, this study described a vertically open-configuration magnet system, which, albeit with artifacts, demonstrated the potential feasibility of eventually being able to conduct dynamic MRI studies with patients in upright and seated positions.27

Yet another group described dynamic magnetic resonance defecography with a superconducting open-configuration magnet system with the patients studied in the sitting position. The authors showed that magnetic resonance defecography is superior to fluoroscopic defecography and is a superb method for the detection of clinically relevant pelvic floor pathology.26 Once again, this study used a small number of patients, so the findings remain to be further confirmed by larger trials. Because open MRI configuration systems still remain in the experimental stages and are not widely available, clinicians should be well aware of this potential drawback of MRI and rely on the entire clinical picture, complemented with other studies and physical examination findings, in making their final decisions. Another potential disadvantage of MRI is its unsuitability for claustrophobic patients and those with cardiac pacemakers.24

Given the numerous advantages of MRI in the study of pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor relaxation, there is a rather wide spectrum of methods used by several investigators, as opposed to a single optimal protocol. Some patients may be imaged at rest, whereas others are studied while straining or during dynamic voiding or evacuation in the MRI scanner. In addition, MRI studies have been done without contrast material, with catheters to identify the urethra, with vaginal and rectal markers, and with vaginal, urethral, rectal, and bladder contrast material.19,28 In general, whereas classic T2-weighted static sequences with correspondingly high spatial resolution are used to assess the anatomy (e.g., levator ani trophicity), fast dynamic sequences are used to study morphologic changes during rest and contraction, straining, and evacuation phases.4,25 The entire imaging study is usually accomplished in 20 to 25 minutes. Information obtained about peritoneal and digestive compartments is especially useful, because it allows evaluation of complex multicompartmental cases of pelvic prolapse in which physical examination appears grossly inadequate. MRI is also very useful in the assessment of postsurgical recurrences.25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree