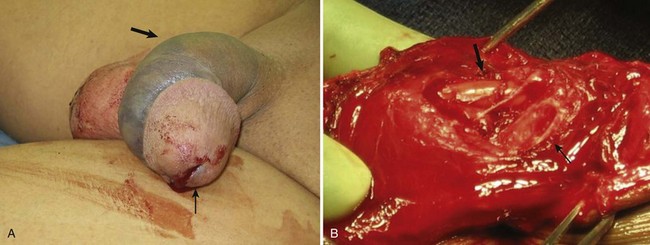

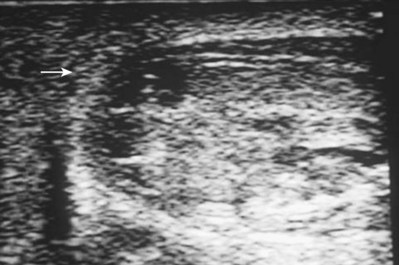

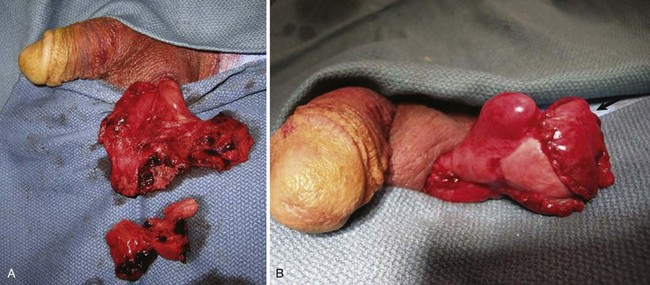

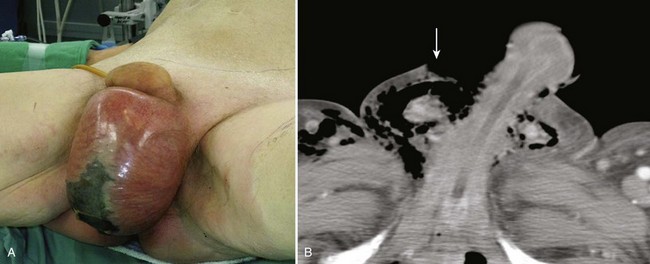

Allen F. Morey, MD, FACS, Daniel D. Dugi, III, MD The tunica albuginea is a bilaminar structure (inner circular, outer longitudinal) composed of collagen and elastin. The outer layer determines the strength and thickness of the tunica, which varies in different locations along the shaft and is thinnest ventrolaterally (Hsu et al, 1994; Brock et al, 1997). The tensile strength of the tunica albuginea is remarkable, resisting rupture until intracavernous pressures rise to more than 1500 mm Hg (Bitsch et al, 1990). When the erect penis bends abnormally, the abrupt increase in intracavernosal pressure exceeds the tensile strength of the tunica albuginea, and a transverse laceration of the proximal shaft usually results. Whereas penile fracture has been reported most commonly with sexual intercourse, it has also been described with masturbation, rolling over or falling onto the erect penis, and myriad other scenarios. In the Middle East, self-inflicted fractures predominate; the erect penis is forcibly bent during masturbation or as a means to achieve rapid detumescence, the practice of taghaandan (Zargooshi, 2000). Mydlo (2001) reported that 94% of fractures in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, were a result of sexual intercourse; Zargooshi (2000) described 69% of fractures in Kermanshah, Iran, as being due to self-manipulation. The tunical tear is usually transverse and 1 to 2 cm in length (Asgari et al, 1996; Mydlo, 2001). The injury is usually unilateral, although tears in both corporeal bodies have been reported (Mydlo, 2001; El-Taher et al, 2004). Although the site of rupture can occur anywhere along the penile shaft, most fractures are distal to the suspensory ligament. Injuries associated with coitus are usually ventral or lateral (Mydlo, 2001; Lee et al, 2007), where the tunica albuginea is the thinnest (Hsu et al, 1994). The diagnosis of penile fracture is often straightforward and can be made reliably by history and physical examination. Patients usually describe a cracking or popping sound as the tunica tears, followed by pain, rapid detumescence, and discoloration and swelling of the penile shaft. If the Buck fascia remains intact, the penile hematoma remains contained between the skin and tunica, resulting in a typical eggplant deformity. If the Buck fascia is disrupted, hematoma can extend to the scrotum, perineum, and suprapubic regions (Fig. 88–1 on the Expert Consult website). The incidence of urethral injury is significantly higher in the United States and Europe (20%) than in Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean region (3%), probably owing to the different etiology—intercourse trauma versus self-inflicted injury (Eke, 2002; Zargooshi, 2002; Jack et al, 2004; Derouiche et al, 2008). Most urethral injuries are associated with gross hematuria, blood at the meatus (Fig. 88–2), or inability to void, although the absence of these findings does not definitively rule out urethral injury (Tsang and Demby, 1992; Mydlo, 2001; Jack et al, 2004). Given that urethral injury occurs not infrequently, preoperative urethrography should be considered when urethral injury is suspected. However, because urethrography can be time consuming and inaccurate (Kamdar et al, 2008), intraoperative flexible cystoscopy is now performed routinely just before catheter placement at the time of penile exploration when urethral injury is suspected. The typical history and clinical presentation of fractured penis usually make adjunctive imaging studies unnecessary. Although cavernosography has been advocated to assist in diagnosis, false-negative studies have been reported (Mydlo, 2001); false-positive studies can result from inadequate filling of one corporeal body and misinterpretation of complex venous drainage (Pliskow and Ohme, 1979; Beysel et al, 2002). Cavernosography is discouraged in the evaluation of a suspected penile fracture because it is time consuming and unfamiliar to most urologists and radiologists (Morey et al, 2004). Ultrasonography, although noninvasive and easy to perform, has also been associated with significant false-negative studies (Koga et al, 1993; Fedel et al, 1996). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a noninvasive and accurate means of demonstrating disruption of the tunica albuginea (Fedel et al, 1996; Uder et al, 2002). Arguments against the routine use of MRI are the expense, limited availability, and time requirements involved with the study. MRI is reasonable in the evaluation of patients without the typical presentation and physical findings of penile fracture. False fracture has been reported in patients who present with penile swelling and ecchymosis, and some even describe the classic “snap-pop” or rapid detumescence typically associated with fracture (Feki et al, 2007). Physical examination may not be adequate for definitive diagnosis of a corporeal tear in these circumstances (Shah et al, 2003). Surgical exploration (Fig. 88–3 on the Expert Consult website) Multiple contemporary publications indicate that suspected penile fractures should be promptly explored and surgically repaired. Although small lateral incisions may be used for localized hematomas or palpable tunical defects (El Bahnasawy and Gomha, 2000; Nasser and Mostafa, 2008), a distal circumcising incision is appropriate in most cases, thus providing exposure to all three penile compartments. Closure of the tunical defect with interrupted 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable sutures is recommended; deep corporeal vascular ligation or excessive debridement of the delicate underlying erectile tissue must be avoided. Induction of an artificial erection with saline or colored dye may aid in locating the corporeal laceration (Shaeer, 2006). Partial urethral injuries should be oversewn with fine absorbable suture over a urethral catheter. Complete urethral injuries should be debrided, mobilized, and repaired in a tension-free fashion over a catheter. Therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics and 1 month of sexual abstinence are recommended. In uncircumcised patients, strong consideration should be given to performing limited circumcision at the conclusion of the repair because wide mobilization of the foreskin may place the distal prepuce at risk for ischemia. Immediate surgical reconstruction results in faster recovery, decreased morbidity, lower complication rates, and lower incidence of long-term penile curvature (Nicolaisen et al, 1983; Orvis and McAninch, 1989; Hinev, 2002; El-Taher et al, 2004; Muentener et al, 2004). Although immediate repair results in penile curvature in less than 5% of patients (El Atat et al, 2008), conservative management of penile fracture has been associated with penile curvature in more than 10% of patients, abscess or debilitating plaques in 25% to 30%, and significantly longer hospitalization times and recovery (Meares, 1971; Nicolaisen et al, 1983; Kalash and Young, 1984; Orvis and McAninch, 1989). Zargooshi (2002) reported in a personal surgical series of 170 patients that surgical management of penile fractures resulted in erectile function comparable to that of a control population. Timing of surgery may also influence long-term success—those undergoing repair within 8 hours of injury had significantly better long-term results than did those having surgery delayed 36 hours after the fracture occurred (Asgari et al, 1996; Karadeniz et al, 1996). The majority of penetrating wounds to the genitalia are due to gunshots (Mohr et al, 2003), and most require surgical exploration. Treatment principles include immediate exploration, copious irrigation, excision of foreign matter, antibiotic prophylaxis, and surgical closure. Gunshot injuries to the phallus are rarely isolated wounds—nearly all victims have significant associated injuries, including abdominal, pelvic, lower extremity, vascular, or additional genitourinary injuries (Bandi and Santucci, 2004; Kunkle et al, 2008). Excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes can be expected with immediate reconstruction (Gomez et al, 1993; Cavalcanti et al, 2006). An artificial erection may be induced to ensure penile straightness, and plication techniques may be used to correct any curvature resulting from closure of a large corporeal injury (Kunkle et al, 2008). Urethral injuries have been reported in 15% to 50% of penile gunshot wounds (Miles et al, 1990; Goldman et al, 1996; Mohr et al, 2003). Retrograde urethrography should be strongly considered in any patient with penetrating injury to the penis, especially with high-velocity missile injuries, blood at the meatus, or difficulty voiding and when the trajectory of the bullet was near the urethra (Goldman et al, 1996; Mohr et al, 2003; Bandi and Santucci, 2004, Phonsombat et al, 2008). Alternatively, intraoperative retrograde urethral injection of methylene blue or indigo carmine may identify the site of injury and the adequacy of closure. If a catheter has already been placed, pericatheter injection may help to ascertain urethral integrity. Urethral injuries due to penetrating trauma should be closed primarily by use of standard urethroplasty principles whenever possible—excellent results have been reported (Miles et al, 1990; Bandi and Santucci, 2004). Patients with urethral injury and extensive tissue damage from high-velocity weapons or close-range shotgun blasts may require staged repair and suprapubic urinary diversion (Bandi and Santucci, 2004), especially those located in the penile urethra (Cavalcanti et al, 2006). The morbidity of animal bites is directly related to the severity of the initial wound. Most victims are boys, and dog bites are the most common injury (Gomes et al, 2001; Van der Horst et al, 2004). Infectious complications are unusual because treatment is sought early. Initial management of dog bites includes copious irrigation, debridement, and immediate primary closure along with prophylactic use of broad-spectrum antibiotic (Cummings and Boullier, 2000). Tetanus and rabies immunizations should be used as appropriate. Because of the risk of polymicrobial infection and the antimicrobial susceptibilities of typical organisms, recommended empiric antimicrobial therapy choices include beta lactam antibiotic with a beta lactamase inhibitor (i.e., amoxicillin-clavulinic acid); a second-generation cephalosporin with anaerobic efficacy (i.e., cefoxitin, cefotetan); or clindamycin with a fluoroquinolone (Talan et al, 1999). Human bites produce contaminated wounds that often should not be closed primarily. Most human bite victims seek medical attention after a substantial delay and thus are more likely to present with gross infection. Empirical antibiotic administration is warranted with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or moxifloxacin (Talan et al, 2003). Traumatic amputation of the penis, although rare, is usually the result of genital self-mutilation. Sixty-five to 87 percent of patients performing genital self-mutilation are psychotic (Greilsheimer and Groves, 1979; Aboseif et al, 1993; Romilly and Isaac, 1996). Psychiatric consultation should be sought in all such cases. Reconstruction of the urethra and reanastomosis of the corporeal bodies with microsurgical repair of dorsal penile vessels and nerves achieves remarkably good results. Patients should be transferred to a facility with microsurgical capabilities; however, if this is unavailable, macroscopic anastomosis of the urethra and corporeal bodies can be performed with good erectile results, albeit with potential compromise of sensation and skin loss. Every attempt should be made to locate, clean, and preserve the severed portion in a “double bag” technique. The distal penis should be rinsed in saline solution, wrapped in saline-soaked gauze, and sealed in a sterile plastic bag. The bag should then be placed into an outer bag with ice or slush (Jezior et al, 2001). Hypothermic injury to the amputated segment can occur if it is in direct contact with ice for a prolonged period. Successful reimplantation is possible after 16 hours of cold ischemia time or 6 hours of warm ischemia (Lowe et al, 1991). If the severed part is not available, the penile stump should be formalized by closing the corpora and spatulating the urethral neomeatus, similar to a partial penectomy procedure for malignant disease. Microvascular reconstruction of the dorsal arteries, vein, and nerves is the preferred method of repair for the amputated penis. Adequate erectile function is possible with both microvascular reanastomosis and macroscopic replantation, with more than 50% of men able to achieve erection with either technique (Bhanganada et al, 1983; Lowe et al, 1991; Aboseif et al, 1993). However, complications such as urethral strictures, skin loss, and sensory abnormalities are all less common with microvascular repair (Jezior et al, 2001). Normal penile sensation returns in 0% to 10% of patients after macroscopic replantation (Bhanganada et al, 1983; Lowe et al, 1991), whereas sensation is present in more than 80% of microscopic replantations (Jordan and Gilbert, 1989; Lowe et al, 1991; Jezior et al, 2001). Penile skin necrosis, sometimes complete, is often a troublesome problem, although less common with microsurgical repair. This is because the blood supply of the skin is independent of the corporeal bodies and because without repair of the superficial vascular structures the penile skin is essentially a free graft (Jezior et al, 2001) Split-thickness skin grafts are applied when the native skin becomes necrotic (Ozturk et al, 2009). An alternative strategy is to denude the phallus of all skin and bury it in the scrotum, leaving the glans exposed, followed by separation of the structures after 2 months (Bhanganada et al, 1983; Jordan and Gilbert, 1989). Adjuvant techniques after penile replant include the use of hyperbaric oxygen to promote healing (Landström et al, 2004; Zhong et al, 2007) or medical leeches on the penis after macroreplantation to augment venous outflow and decrease edema (Mineo et al, 2004). Key Points: Step-by-Step Approach to Penile Reattachment Zipper injuries to the penis usually happen more often to impatient boys or intoxicated adults. Multiple maneuvers are available to free the entrapped skin and to remove the mechanism. After a penile block the zipper slider and adjacent skin can be lubricated with mineral oil, followed by a single attempt to unzip and untangle the skin (Kanegaye and Schonfeld, 1993; Mydlo, 2000). The cloth material connected to the zipper can be incised with perpendicular cuts in between each zipper tooth to release the lateral support of the zipper, allowing the device to fall apart and release the trapped skin (Oosterlinck, 1981). A bone cutter or similar tool can be used to cut the median bar (diamond-shaped connection) of the slider. This maneuver allows separation of the upper and lower shields of the slider, and the entire zipper falls apart (Flowerdew et al, 1977; Saraf and Rabinowitz, 1982). Some children may require more than local anesthesia or sedation; circumcision or an elliptical skin excision can be performed in the operating room under anesthesia (Yip et al, 1989; Mydlo, 2000). String, hair, and rubber bands can be incised. Initial attempts to remove a solid constricting device causing penile strangulation involve lubrication of the shaft and foreign body and attempted direct removal. Edema distal to the strangulation often makes removal difficult. A string or latex tourniquet can be wrapped around the distal shaft to decrease swelling and to improve the odds of removing the device with lubrication. If the constricting object cannot be severed or removed, a string technique should be considered (Browning and Reed, 1969; Vahasarja et al, 1993; Noh et al, 2004). A thick silk suture or umbilical tape is passed proximally under the strangulation object and wound tightly around the penis distally toward the glans. The tag of suture or tape proximal to the ring is grasped; unwinding from the proximal end will push the object distally. Glanular puncture with a needle or blade will allow escape of dark trapped blood and improve the odds of removing the object with the string method (Browning and Reed, 1969; Noh et al, 2004). Plastic constricting devices can be incised with a scalpel or an oscillating cast saw (Pannek and Martin, 2003), but metal objects present a more difficult challenge. Readily available hospital equipment (ring cutters, bolt cutters, dental drills, commercially available rotary tools, orthopedic and neurosurgical operative drills) may not be adequate to cut through heavy iron or steel items. The use of industrial drills, steel saws, hacksaws, saber saws, and high-speed electric drills has been reported (Perabo et al, 2002; Santucci et al, 2004). On occasion, fire department and emergency medical services equipment may be required to cut through iron and steel rings. The phallus should be protected from thermal injury, sparks, and the cutting blade by use of tongue depressors, sponges, or malleable retractors; continuous saline irrigation may be used for cooling. Such elaborate undertakings are best accomplished in the operating room under anesthesia. If decompression is delayed and the patient is distended and unable to void, a suprapubic bladder catheter should be placed. Outcomes are generally good with device removal alone, although the surgeon should be prepared to consider reconstructive techniques such as skin grafting if the strangulation injury causes skin necrosis (Ivanovski et al, 2007). Although the testis is relatively protected by the mobility of the scrotum, reflexive cremasteric muscle contraction, and its tough fibrous tunica albuginea, blunt injury (usually the result of assault, sports-related events, and motor vehicle accidents) can result in rupture of the tunica albuginea, contusion, hematoma, dislocation, or torsion of the testis. Testicular injury results from blunt trauma in about 75% of cases (McAninch et al, 1984; Cass and Luxenberg, 1991), whereas penetrating injuries due to firearms, explosions, or impalement make up the remainder. Whereas only 1.5% of blunt testis injury involves both gonads, about 30% of penetrating scrotal trauma results in bilateral injury (Cass and Luxenberg, 1988, 1991). Like penetrating urethral injuries, penetrating scrotal trauma (roughly 80%) usually involves neighboring structures, including the thigh, penis, perineum, bladder, urethra, and/or femoral vessels (Gomez et al, 1993; Cline et al, 1998). In contemporary military conflicts, genital wounds account for a larger percentage of urologic injuries because of the powerful explosive weapons involved and absence of protective body armor over the genitalia (Thompson et al, 1998). Blast injuries are typically associated with extensive scrotal skin loss, multiple projectile injuries of both testes, and concomitant extensive destruction of the lower extremities and abdomen. Ultrasonography can be helpful to assess the integrity and vascularity of the testis in equivocal cases. Ultrasonography is rapid, readily available, and noninvasive. Because it may be operator dependent, false-positive and false-negative studies range from 56% to 94% (Fournier et al, 1989; Corrales et al, 1993; Herbener, 1996; Dreitlein et al, 2001). Ultrasound findings suggestive of testicular fracture include a heterogeneous echo pattern of the testicular parenchyma and disruption of the tunica albuginea (Micallef et al, 2001; Buckley and McAninch, 2006) (Fig. 88–4). Although ultrasonography may assist in detection of testicular fracture or hematoma (Guichard et al, 2008), a normal or equivocal ultrasound study should not delay surgical exploration when physical examination findings suggest testicular damage; definitive diagnosis is often made in the operating room. Although MRI may effectively demonstrate testicular integrity, its widespread use is not the norm because of expense, limited availability, and potential delay in definitive surgical care of the patient (Serra et al, 1998; Muglia et al, 2002; Kim et al, 2009). Differential diagnosis of testicular fracture includes hematocele without rupture, torsion of the testis or an appendage, reactive hydrocele, hematoma of the epididymis or spermatic cord, and intratesticular hematoma. A nonpalpable testis in a trauma patient should raise the possibility of dislocation outside the scrotum. This entity usually occurs after motorcycle crashes when extreme forces on the scrotum expel the testis into surrounding tissues such as the superficial inguinal pouch (50%) or to a pubic, penile, pelvic, abdominal, or perineal location (Schwartz and Faerber, 1994; Bromberg, 2003). Bilateral dislocation after trauma has been reported (Bromberg et al, 2003; O’Brien et al, 2004). Manual or surgical reduction of the displaced testis is indicated. Finally, approximately 5% of spermatic cord torsions are believed to be precipitated by trauma; torsion should be considered in all cases of significant scrotal pain without signs or symptoms of major scrotal trauma (Elsaharty et al, 1984; Manson, 1989; Lrhorfi et al, 2002). Early exploration and repair of testicular injury is associated with increased testicular salvage, reduced convalescence and disability, faster return to normal activities, and preservation of fertility and hormonal function (Kukadia et al, 1996). Minor scrotal injuries without testicular damage can be managed with ice, elevation, analgesics, and irrigation and closure in some circumstances. The objectives of surgical exploration and repair are testicular salvage, prevention of infection, control of bleeding, and reduced convalescence. Transverse scrotal incision is preferable in most cases. The tunica albuginea should be closed with small absorbable sutures after removal of necrotic and extruded seminiferous tubules. Even small defects in the tunica albuginea should be closed, because progressive swelling and intratesticular pressure can continue to extrude seminiferous tubules. Every attempt to salvage the testis should be performed; loss of capsule tissue may require removal of additional parenchyma to allow closure of the remaining tunica albuginea. A flap or graft of tunica vaginalis may be used to cover a large defect in the tunica albuginea in an otherwise salvageable testis (Fig. 88–5); synthetic grafts are not recommended for this purpose (Ferguson and Brandes, 2007). Significant intratesticular hematomas should be explored and drained even in the absence of testicular rupture to prevent progressive pressure necrosis and atrophy, delayed exploration (40%), and orchiectomy (15%) (Cass and Luxenberg, 1988). Significant hematoceles should also be explored, regardless of imaging studies, because up to 80% are caused by testicular rupture (Vaccaro et al, 1986). Penetrating scrotal injuries should be surgically explored to inspect for vascular and vasal injury; as in blunt trauma the same principles of salvage, hemostasis, and reconstruction apply. The vas deferens is injured in 7% to 9% of scrotal gunshot wounds (Gomez et al, 1993; Brandes et al, 1995). The injured vas should be ligated with nonabsorbable suture and delayed reconstruction performed if necessary. Approximately 30% of gunshot wounds injure both testes—exploration of the contralateral testis should be considered, depending on the findings of physical examination and the path of the projectile. Nonoperative management of testicular rupture is frequently complicated by infection, atrophy, necrosis, chronic unrelenting pain, and delayed orchiectomy. Testicular salvage rates exceed 90% with exploration and repair within 3 days of injury (Del Villar et al, 1973; Schuster, 1982; Fournier et al, 1989; Cass and Luxenberg, 1991) versus orchiectomy rates threefold to eightfold higher with conservative management and delayed surgery (Cass and Luxenberg, 1991). Testicular salvage rates with conservative management are as low as 33%, with delayed orchiectomy rates between 21% and 55% (Schuster, 1982; Cass and Luxenberg, 1991; McAleer and Kaplan, 1995). Approximately 45% of patients initially managed conservatively will ultimately undergo surgical exploration for pain, infection, and persistent hematoma (Del Villar et al, 1973; Cass and Luxenberg, 1991). Convalescence and time of return to normal activities are significantly reduced after early surgical repair. Unlike blunt testis rupture, for which salvage rates are very high, penetrating testicular trauma has historically been associated with gonad salvage in only 32% to 65% of cases (Bickel et al, 1990; Gomez et al, 1993; Brandes et al, 1995; Cline et al, 1998). Improved salvage rates as high as 75% have been reported both in recent civilian (Phonsombat et al, 2008) and combat series (Waxman et al, 2009). The overwhelming majority of surgical patients have adequate preservation of hormonal and fertility function (Kukadia et al, 1996). Sperm production has been documented in men with appropriately repaired bilateral testis rupture and bilateral penetrating injuries (Pohl et al, 1968; Brandes et al, 1995). Urologists may be consulted for opinion and guidance with regard to boys with a solitary testis who play a contact sport. Fortunately, testicular injuries are exceedingly rare in boys involved in individual or team contact sports and recreational activities (McAleer et al, 2002; Wan 2003a, 2003b). Parents should be appropriately counseled and a protective cup device recommended. The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness (2001) recommended that many factors be considered regarding whether to allow a child with a solitary testis to play sports; their recommendation was an unqualified yes in this circumstance. Necrotizing gangrene due to polymicrobial infection in the genital area, or Fournier gangrene, is the most common cause of extensive genital skin loss (McAninch et al, 1984). Skin loss is iatrogenic, caused by the necessity for acute debridement of necrotic genital skin when the patient is seen initially. Penile skin loss can result from traction by mechanical devices, such as farm or industrial machinery, or by suction devices, such as vacuum cleaners. Because the superficial penile tissue is loose areolar tissue, it is often torn free without damage to the underlying structures. Significant scrotal skin loss resulting from penetrating trauma is uncommon, but it has been seen more recently in battlefield explosive injuries (Fig. 88–6). Penile burns, although rare, are often full thickness because the penile skin is so thin (Horton, 1990). Constricting bands placed on the penis can result in significant skin loss, although a more common injury involves direct pressure necrosis under the band, which usually heals well with device removal alone. Although both cellulitis and Fournier gangrene are commonly associated with significant genital edema and erythema, skin ischemia is the hallmark of Fournier gangrene. The finding of loss of scrotal rugae is highly suggestive of tissue necrosis. Scrotal ultrasonography (Kane et al, 1996) and computed tomography (CT) may reveal subcutaneous air, a helpful indicator of necrotizing infection (Fig. 88–7). In most cases of Fournier gangrene, multiple debridements of ischemic or frankly necrotic skin are required over a period of several days until active infection is controlled. Wounds are treated with frequent wet-to-dry dressing changes or with vacuum-assisted closure therapy (Cyzmek et al, 2009) until primary coverage is planned. Inspection at least daily by the surgical team is mandatory. Suprapubic urinary diversion should be strongly considered for extensive injuries to simplify wound care and to prevent urethral complications related to prolonged catheterization. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment has been advocated as an adjunctive measure to promote wound healing, although the authors do not recommend this owing to the considerable increase in expense and logistical complexity in the absence of proven benefit (Mindrup et al, 2005). In selected uncircumcised patients, mobilization of redundant foreskin may allow primary closure of middle to distal penile skin loss (Horton, 1990). Scrotal rotation flaps can be used for more proximal defects if skin loss is limited, but the hair-bearing nature of scrotal skin risks an unacceptable cosmetic result. Local flaps, such as from the abdomen and thigh, also can be used but are cosmetically inferior to split-thickness skin grafts. Skin coverage with avulsed skin should be avoided because it often becomes necrotic. Thick (0.012- to 0.015-inch), nonmeshed, split-thickness skin grafts (McAninch et al, 1984) are preferred for penile reconstruction. Meshed grafts can be used but have a tendency to contract and are cosmetically inferior to unmeshed grafts. Grafts are usually harvested from the anterior thigh with a pneumatic dermatome. If grafts are to be used, care must be taken to remove any subcoronal skin remaining after debridement. Lymphatic obstruction of this distal foreskin, if it is not excised, will result in circumferential lymphedema (McDougal, 2003). Graft stabilization in the immediate postoperative period may be achieved by either tie-over-bolster technique or with a circumferential vacuum dressing (Weinfeld et al, 2005; Senchenkov et al, 2006). Skin grafts placed on the penile shaft never regain normal sensation (Horton, 1990), although sexual function is often preserved because of intact sensation in the glans. Scrotal skin loss defects of up to 50% can often be closed directly. For extensive injuries, the testes may be placed in thigh pouches or treated with wet dressings for up to several weeks until reconstruction (Cummings and Boullier, 2000; Gomes et al, 2001). Thigh pouches are not recommended initially, until the infection is stabilized, because transmission of the infectious process into uninvolved tissues may occur.

Injuries of the External Genitalia

Penis

Fracture

Etiology

Diagnosis and Imaging

![]() The swollen, ecchymotic phallus often deviates to the side opposite the tunical tear because of hematoma and mass effect. The fracture line in the tunica albuginea may be palpable. Because fear and embarrassment are commonly associated, the patient’s presentation to the emergency department or clinic is sometimes significantly delayed.

The swollen, ecchymotic phallus often deviates to the side opposite the tunical tear because of hematoma and mass effect. The fracture line in the tunica albuginea may be palpable. Because fear and embarrassment are commonly associated, the patient’s presentation to the emergency department or clinic is sometimes significantly delayed.

![]() or evaluation with MRI should be considered. Another condition that may mimic penile fracture is rupture of the dorsal penile artery or vein during sexual intercourse (Armenakas et al, 2001; Bar-Yosef et al, 2007).

or evaluation with MRI should be considered. Another condition that may mimic penile fracture is rupture of the dorsal penile artery or vein during sexual intercourse (Armenakas et al, 2001; Bar-Yosef et al, 2007).

Management

Outcome and Complications

Gunshot and Penetrating Injuries

Gunshot Wounds

Animal and Human Bites

Amputation

Zipper Injuries

Strangulation Injuries

Testis

Etiology

Diagnosis

Management

Outcome and Complications

Genital Skin Loss

Etiology

Diagnosis and Initial Management

Penile Reconstruction

Scrotal Reconstruction

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Genital and Lower Urinary Tract Trauma