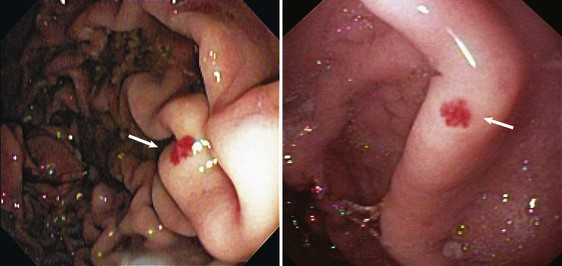

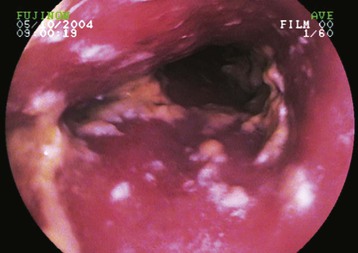

Gemma Bircher, Graham Woodrow Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and disease are common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including those receiving renal replacement therapy (Table 87-1). Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting can arise from uremic toxicity. They may indicate the need to start dialysis or may be a manifestation of inadequate dialysis clearances. GI disturbances contribute to the development of malnutrition and wasting. These common complications of advanced CKD carry an adverse prognosis for survival. Some GI conditions are a result of uremia or the effects of renal replacement therapy. Other GI symptoms are manifestations of conditions also responsible for the renal disease. Medications may result in a range of GI complications in patients with CKD. Glossitis can result from deficiency of iron, vitamin B12, other B vitamins, or folic acid. Halitosis is a feature of uremia, and reduced taste sensation or abnormal or unpleasant taste can impair dietary intake. Dental disease may prevent adequate nutrition. Gingival hyperplasia is a frequent complication of treatment with calcium channel blockers or cyclosporine. Oral candidiasis occurs in patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs including corticosteroids, in those undergoing antibiotic therapy, in patients with diabetes, and in older malnourished individuals. If extensive, particularly with esophageal involvement, it may lead to dysphagia (Fig. 87-1). Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a common complaint that is defined by symptoms of heartburn or mucosal changes arising from reflux of caustic gastric contents into the esophagus. It occurs more frequently in patients with CKD because of GI dysmotility or delayed gastric emptying and may be more prevalent with peritoneal dialysis (PD) because of increased intra-abdominal pressure.1 It is more common in patients with scleroderma because of reduced esophageal peristalsis. Esophagitis also results from the irritant effects of drugs, including slow-release potassium preparations, tetracyclines, iron preparations, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and bisphosphonates. The diagnosis is made from the patient’s symptoms. Typical features appear on endoscopy but may be absent in symptomatic patients. Other investigations include 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring and demonstration of reflux on barium swallow examination. It is important to consider ischemic cardiac disease in CKD as an alternative cause of atypical symptoms. Management includes weight loss in obese patients; avoidance of bedtime snacks, fatty foods, cigarettes, and alcohol; and raising the head of the patient’s bed. Proton pump inhibitors are the most effective medical treatment, and maintenance therapy may be required. Other drugs include histamine H2 receptor antagonists and antacid preparations. Sucralfate should be avoided in patients with CKD because of the risk of aluminum accumulation. In the early days of dialysis, peptic ulceration and GI hemorrhage were major complications of renal failure. However, with effective drug therapies and improvement in dialysis therapy, peptic ulcer disease is not more common in CKD than in the general population, although it remains an important cause of GI hemorrhage. Peptic ulcers in patients with CKD are more often multiple than in the general population and situated in a postbulbar position.2 Hemorrhage occurs more often, but pain is less frequent.2 Gastritis and duodenitis are common in patients with CKD and abdominal symptoms. Hypergastrinemia occurs with CKD but is not important in causation of gastritis, duodenitis, or peptic ulcers. Despite high urea concentrations in patients with CKD, incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection is not increased.3 Increased susceptibility of gastric and duodenal mucosa to damage in CKD may be an underlying mechanism. The presence of H. pylori infection in PD has been suggested as a possible cause of anorexia, inflammation, and malnutrition.4 Dyspepsia without other warning features (weight loss, vomiting, hemorrhage) may be managed by testing for H. pylori with a breath test or stool antigen test (which are valid in CKD) and an empirical course of acid-suppressing therapy. Persistent symptoms of new onset in patients older than 55 years warrant upper GI endoscopy to exclude malignant disease. The frequent coexistence of other symptoms in CKD, such as nausea, vomiting, and weight loss, may lead to a lower threshold for performance of endoscopy. Management includes use of proton pump inhibitors and histamine H2 receptor antagonists. There is a risk of excess calcium and magnesium absorption with some antacids in CKD, and aluminum- or bismuth-containing preparations should be avoided. Gastric emptying is impaired in uremia (possibly to a greater degree in PD)5,6 and is affected by some conditions leading to renal disease, particularly diabetes and amyloidosis. This results in reduced appetite, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, and malnutrition. Mechanisms in uremia may include autonomic neuropathy and retained GI peptides. The diagnosis is confirmed by scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying. It may be suspected when endoscopy demonstrates residual gastric contents despite fasting. Endoscopy is important to exclude gastric outlet obstruction. Reversible causes should be addressed, including optimization of diabetic control, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and discontinuation of drugs that impair gastric emptying (e.g., those with anticholinergic and opioid effects). Dietary measures, with frequent smaller low-fat meals and avoidance of nondigestible solids, are often disappointing. Antiemetic agents are also often ineffective. The mainstay of treatment is prokinetic drug therapy, including metoclopramide, domperidone, and erythromycin. Prokinetic drugs improve nutritional state in patients with delayed gastric emptying.7 Nutritional support through feeding nasoenteric or jejunostomy tubes may be required. Diverticular disease has an incidence in CKD similar to that in the general population, except in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), in whom it is increased.8 It presents as acute diverticulitis or colonic perforation and is associated with PD peritonitis caused by enteric organisms. There is a greater risk of bleeding in CKD (because of uremic bleeding tendency) and perforation with high-dose corticosteroids (e.g., after renal transplantation). Constipation is common in CKD. Predisposing factors include drugs, dietary restrictions, low oral fluid intake, and electrolyte abnormalities, including hypercalcemia. In PD, constipation results in impaired dialysate drainage and catheter malposition. Severe constipation is a risk factor for large bowel perforation. Management includes stool-softening agents, stimulant laxatives, and fiber preparations. Drugs predisposing to constipation include calcium-based phosphate binders, sevelamer, oral iron, opioid analgesics, and calcium resonium. Colonic perforation may occur in CKD from a number of causes. These include diverticulitis, fecal impaction, and dialysis-related amyloidosis. This condition has a higher mortality in CKD patients. Pseudo-obstruction presents with acute or more chronic clinical features of abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. It arises from disordered gut motility and is more common in dysmotility states, such as diabetes, amyloidosis, and scleroderma. Drugs that reduce bowel motility and electrolyte disturbance such as hypokalemia predispose to pseudo-obstruction, and it may be acutely precipitated by surgery, constipation, and retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Investigations include plain abdominal radiography, computed tomographic scanning, and bowel contrast studies. Management includes nutritional support (which may require parenteral feeding) and prokinetic agents. Nasogastric tube insertion and aspiration may be required for symptomatic control. Complications include intestinal perforation9 and bacterial overgrowth. Intestinal ischemia is an important cause of an acute abdomen in older CKD patients. A proportion of cases result from nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia, in which there is no critical vascular occlusion.10 It may be precipitated by excess fluid removal by hemodialysis (HD). Predisposing factors include hypotension, cardiac failure, hypoxia, increased plasma viscosity, and constipation (which increases intraluminal pressure, impairing vascular perfusion). Presentation is with abdominal pain, diarrhea, or lower GI bleeding. Abdominal signs such as peritonism can be misleadingly modest at presentation, but there is often peripheral neutrophil leukocytosis and progressive lactic acidosis. Milder cases may settle with hemodynamic resuscitation. Patients with more severe cases with features of peritonism and intestinal infarction require laparotomy and have a high mortality. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage is an important complication of CKD, with increased incidence compared with the general population. Causes include a greater incidence of lesions such as gastritis and duodenitis,11 angiodysplasia, and, more rarely, dialysis-related amyloidosis and systemic vasculitis (Fig. 87-2). Uremic hemostatic defects and anticoagulation during HD are also important. Upper GI endoscopy is the major diagnostic investigation in upper GI bleeding and also allows therapeutic procedures to stop bleeding. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are performed for lower GI bleeding. Investigations in which the cause remains unclear include angiography, small bowel enteroscopy or capsule study, and radiolabeled red cell scanning. Resuscitation requires careful monitoring in patients with CKD. Adequate fluid replacement to maintain renal perfusion in patients not on dialysis or with residual renal function in patients on dialysis, but avoiding fluid overload, is crucial. Monitoring of serum potassium with avoidance of hyperkalemia complicating blood transfusion is also important. Correction of coagulation defects in patients with CKD includes optimization of dialysis clearance, correction of anemia, and use of DDAVP or cryoprecipitate. Drugs that increase bleeding risk should be discontinued when possible. HD, when it is required, should be performed without heparin for anticoagulation. Specific treatment is directed at the cause of hemorrhage. Bleeding from angiodysplasia in HD may improve on transfer to PD.12 The presence of CKD increases the risk of mortality in GI hemorrhage.10 Clostridium difficile is a major cause of nosocomial diarrheal illness. Clinical manifestations vary from mild diarrheal illness to severe pseudomembranous colitis (Fig. 87-3). Patients with CKD are at risk of more frequent or severe infection and have a higher resulting mortality.13 Reasons include the older age of CKD patients, frequent use of acid-suppressing drugs, and antibiotics. Diagnosis is made by identifying C. difficile toxin in diarrheal stools. In severe cases, there are radiologic appearances of acute colitis with mucosal edema, but these are not specific for C. difficile. A pseudomembrane may be visualized on sigmoidoscopy, but diarrhea can occur in its absence. The precipitating antibiotic should be stopped if possible. Oral metronidazole is first-line antibiotic therapy; oral vancomycin is used if there is intolerance of or failure to respond to metronidazole. Fidaxomicin is a newer, expensive agent that may be used for recurrent infection, and intravenous immunoglobulin has been used for refractory cases.14 Fluid and electrolyte replacement are important, and drugs that reduce diarrhea or impair gut motility must be avoided because they may precipitate toxic megacolon. Colectomy may be required in life-threatening disease. C. difficile infection is a major problem in the hospital setting, including renal units. Preventive measures, including hand washing, cleanliness of physical environment, and isolation of affected inpatients with barrier nursing, are essential. Antibiotic policies should minimize use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which induce C. difficile infection. There is some evidence suggesting that acute pancreatitis is more common in CKD, and the incidence may be greater in PD than in other CKD patients.15 Most cases are secondary to biliary tract disease or alcohol use or are idiopathic. Rarer causes, in CKD patients, are hypercalcemia, vasculitis, and drugs including corticosteroids, azathioprine, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and diuretics. Serum amylase is the usual diagnostic measure, although concentrations are normally elevated up to threefold in renal failure and are lowered in PD patients receiving icodextrin dialysate (because of competitive inhibition of icodextrin and metabolites with the amylase assay). Serum lipase is an alternative diagnostic marker (although it is also elevated in uremia). Amylase and lipase concentrations may be measured in dialysate in PD patients with suspected pancreatitis. Radiology, including ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, is useful to confirm the diagnosis and to detect underlying biliary disease and complications such as pancreatic necrosis and pseudocyst formation. In PD patients with acute pancreatitis, dialysate may become cloudy with increased leukocytes, hemorrhagic, or dark brown (cola colored). Some causes of acute abdominal pain occur more commonly in or are specific to CKD patients. A high index of suspicion for ischemic bowel is important because of the frequency of vascular disease in CKD. Pain may result from complications of autosomal polycystic kidney disease. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage can arise from anticoagulation, including during HD. In PD, abdominal pain arises from peritonitis, acidity of the fluid (causing dialysate infusion pain), catheter malposition, constipation, and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Other surgical conditions need to be distinguished from dialysis-specific causes. Although air uncommonly enters the peritoneal cavity during PD, in the setting of acute abdominal symptoms the finding of free gas on radiologic imaging of the abdomen suggests visceral perforation. A number of conditions result in both renal and GI manifestations (Table 87-2). Table 87-2 Gastrointestinal (GI)-renal syndromes: conditions typically resulting in both renal and GI disease. CKD, Chronic kidney disease. Diabetes is commonly complicated by disordered gut motility. Gastroparesis needs to be distinguished from uremic upper GI symptoms. Diarrhea caused by diabetic enteropathy is also common, classically is nocturnal, and usually is neurogenic in origin. Treatment is usually by antimotility agents. Bacterial overgrowth is uncommon and is diagnosed by the hydrogen breath test. GI symptoms may be exacerbated by drug treatments for diabetes, including metformin and α-glucosidase inhibitors. Gastroparesis results in difficulties with glycemic control, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, drug malabsorption, and malnutrition. The speed of colonic transport is decreased in diabetes, which may result in constipation. Gastrointestinal manifestations of vasculitis include intestinal ischemia or infarction, hemorrhage, and perforation with peritonitis. Abnormal liver function test results arise from hepatitis, and cholecystitis and pancreatitis have been described. Serositis with abdominal pain is a feature of systemic lupus erythematosus. Abdominal pain, vomiting, and GI hemorrhage are typical of Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Gastroenterology and Nutrition in Chronic Kidney Disease

Gastrointestinal Problems in Chronic Kidney Disease

Gastrointestinal Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease

Oral Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Esophagitis

Peptic Ulcer Disease, Gastritis, and Duodenitis

Delayed Gastric Emptying and Gastroparesis

Large Bowel Disorders

Gastrointestinal Pseudo-obstruction

Vascular Disease of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Clostridium difficile Infection

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute Abdomen

Gastrointestinal-Renal Syndromes

Gastrointestinal-Renal Syndromes: Conditions Typically Resulting in Both Renal and Gastrointestinal Disease

Disorder

Renal Involvement

GI Involvement

Diabetes

Proteinuria, CKD

Gastroparesis, diabetic enteropathy, constipation

Systemic vasculitis

Proliferative glomerulonephritis, CKD

Intestinal ischemia, GI hemorrhage, bowel perforation, hepatobiliary involvement, acute pancreatitis

Systemic amyloidosis

Nephrotic syndrome, CKD

Diarrhea, malabsorption, splenic rupture

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

CKD, cyst hemorrhage, and infection

Abdominal pain (from renal or hepatic cysts), diverticular disease, hernia

Inflammatory bowel disease

AA amyloidosis, drug-induced interstitial nephritis, IgA nephropathy, oxalate renal calculi (with terminal ileal Crohn disease)

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, GI hemorrhage, malabsorption

Scleroderma

CKD, acute scleroderma renal crisis

Dysphagia, constipation, malabsorption, and bacterial overgrowth

Fabry disease

Hematuria, proteinuria CKD

Abdominal pain, episodes of diarrhea, or constipation

Celiac disease

IgA nephropathy

Malabsorption, iron-deficiency anemia

IgG4-related tubulointerstitial nephritis

Tubulointerstitial nephritis

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Diabetes

Systemic Vasculitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastroenterology and Nutrition in Chronic Kidney Disease

Chapter 87