Chapter 91 FOCAL NEUROMUSCULAR THERAPIES FOR CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN SYNDROMES IN WOMEN

Women have been suffering from chronic pelvic pain (CPP) syndromes presumably since the age of primate evolution. Except for endometriosis, there is little in the way of objective biologic findings to explain the pathophysiology of these complaints. In most instances, the diagnostic terms for disorders of pain in the pelvis relate to a specific organ with no identifiable mechanistic relationship. This chapter attempts to identify the common urologic/gynecologic disorders commonly considered CPP syndromes, explores the evidence for neuromuscular disorder, and reviews most of the local and focused therapeutic approaches that may be beneficial in the management of these conditions. I am specifically avoiding consideration of any pharmaceutical therapy. The objective is to suggest an integration of both physical and behavioral treatments to elicit relief from these life-altering conditions while we await more elucidation about the biologic mechanisms involved.

BIOFEEDBACK THERAPY

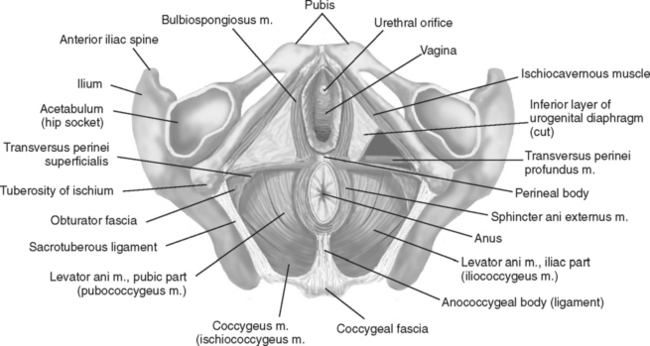

Biofeedback therapy for pelvic disorders has primarily been used to manage pelvic floor disorders and urinary incontinence, but it has also become quite valuable for patients with pelvic pain disorders. Biofeedback and behavioral changes can play a role in effecting clinical improvement in urologic problems including pelvic pain (vulvar vestibulitis), irritative voiding symptoms, recurrent urinary tract infections, and urinary incontinence. Biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction involves the use of surface internal (vaginal and rectal) electrodes that transduce muscle potentials into visual and auditory signals; by this means, patients learn to be aware and control (increase or decrease) voluntary muscle activity. Physical exercises are then used to affect the pelvic floor muscles (Fig. 91-1).

Figure 91-1 Pelvic floor muscles as seen from below in the supine female subject.

(Redrawn from Travell JG, Simons DG: Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Vol 2, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998.)

In the late 1940s, Dr. Arnold Kegel, an obstetrician/gynecologist, invented the first feedback device that was used for pelvic muscle rehabilitation to treat female urinary incontinence. The processes and procedures of biofeedback therapy have been described.1,2 A general overview for application to pain management was summarized by Tan and colleagues.3

Two major subtypes of biofeedback therapy are currently in practice. The traditional form is known as peripheral or somatic feedback, which assists in teaching patients to be more physiologically aware of abnormal muscle tension and adjust accordingly. Surface electromyography (EMG), heart rate and blood pressure, skin temperature, and galvanic skin responses are used. Applications of peripheral biofeedback include neuromuscular re-education (for patients after stroke), musculoskeletal therapy, urinary4 and fecal incontinence, and pelvic pain including CPP syndromes in men,5,6 vulvodynia,7 and dysmenorrhea.8,9 A second subtype of biofeedback therapy uses electroencephalography (EEG) and is classified as central biofeedback, neurofeedback, or neurotherapy. With the exception of migraine, most of the research with this therapy has been in areas other than pain, such as treatment of alcohol or additive disorders.

Glazer and coworkers reported their experience in two separate open-ended, uncontrolled studies using EMG biofeedback of the pelvic floor musculature to treat patients with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, a subset of vulvodynia.7,10 The rationale for study was based on the knowledge that patients with vulvar vestibulitis usually have hyperirritability of the pelvic floor muscles.7,11 The hypothesis has been put forward that destabilization of pelvic floor muscles is a factor in perpetuating the vulvar skin disturbances and accompanying pain. Travell and Simons reported that muscle disturbances are reflected in discord of EMG recordings.12 In the studies by Glazer and associates, patient diagnosis was confirmed by physical examination, and the initial pelvic floor EMG assessments were performed with a surface EMG single-user vaginal sensor; monthly evaluations followed during clinic visits.7,10 A portable EMG biofeedback device and instructions for pelvic floor rehabilitation exercises were provided to each patient for twice-daily in-home practice. Patient demographics were similar in both studies; average duration of symptoms was 3.5 years (range, 2 to 6 years), and most had abstained from sexual intercourse for an average of 1 year.

In the first Glazer study of 33 women, symptoms ranged from only introital dyspareunia to chronic, intense pain provocation.7 After 16 weeks of practice, pelvic floor contraction increased by 95%, resting tension levels decreased by 68%, and muscle instability at rest decreased by 62%. Based on subjective reporting at each evaluation, maximum pain decreased from the previous evaluation to a average of 83%. Many patients (22 [79%] of 28) resumed intercourse. Half of the women remained pain free at follow-up 6 months later. In the second study, 29 women with level 2 and 3 vulvar vestibulitis were enrolled.10 Level 2 includes women who have pain with intercourse that requires interruption or discontinuance of coitus, and level 3 includes those who have pain with intercourse that prevents any attempt at insertion or coitus.13 With biofeedback therapy, increased muscle stabilization was associated with decreased pain; as pain decreased, patients were more likely to resume intercourse. After therapy, 85% (24 of 29) had negligible or mild pain, and 69% resumed sexual activity.

Neuromuscular education of the pelvic floor muscles to ameliorate chronic pain has been supported by the studies in men with CPP syndromes. In a preliminary study of 19 patients using biweekly sessions of biofeedback and home exercises, significant decreases (approximately 50%) in pain and urgency scores were reported by Clemens and colleagues.5 However, only about half of the patients completed the full course of therapy. In the study by Cornel and colleagues, biofeedback rehabilitation of 25 men with type III CPP involved verbal guidance and feedback through palpation of pelvic floor muscles and EMG measurements to teach correct muscle contraction and relaxation.6 Significant improvements in the National Institutes of Health–Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) total scores, with pain and micturition domains decreasing an average of 50%, were associated with a significant 35% decrease in pelvic muscle tonus after treatment.

MYOFASCIAL TRIGGER POINT RELEASE THERAPY

Definition and Basic Science Investigation

A long list of disorders in women has been shown to involve the musculoskeletal system; these include the levator ani syndrome, vulvodynia, vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, dyspareunia, vaginismus, coccygodynia, interstitial cystitis (IC) or painful bladder syndrome, pelvic floor tension myalgia, urge-frequency syndrome, urethral syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, proctodynia, proctalgia fugax, and pudendal nerve entrapment,7,14–18 and, in men, nonbacterial prostatitis and CPP syndromes.19,20 Often overlooked and misunderstood as a musculoskeletal source of pelvic pain are myofascial trigger points (MTrPs). More than 50 years ago, Dr. Janet Travell introduced the phenomenon of referred pain and referred motor activity attributed to trigger points (TrPs) in skeletal muscles, which were later shown to be a causative factor in myofascial pain and dysfunction. Our understanding of MTrPs and their relation to myofascial pain syndromes continues to evolve, as shown in Table 91-1.

Table 91-1 Progress of Discovery and Understanding of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Myofascial Trigger Points

An MTrP is defined as a highly localized and hyperirritable spot in a palpable taut band or tender nodule of skeletal muscle fibers.16,21 MTrPs can be located in one or more muscles, and common clinical characteristics exist.22–26 Muscles can become “knotted” and inelastic and unable to contract or relax. Stimulated by digital palpation or needling, active MTrPs characteristically elicit local pain or a referred pain similar to that of the patient’s complaint of pain or aggravation of existing pain. A local twitch response is also a confirmatory sign of an MTrP. Latent MTrPs are clinically asymptomatic and do not cause pain with compression. Both active and latent MTrPs are associated with muscle weakness on active contraction and reduced range of motion, and MTrPs can be perpetuated or aggravated by mechanical stress, metabolic, endocrine, and nutritional inadequacies, as well as psychological factors.21 Depression and chronic pain are often closely associated, and it should be appreciated that depression and anxiety are frequently consequent to unresolved symptoms.

Recent reviews present the current understanding of MTrPs and an historical summary of the development of these concepts.27,28 An integrated hypothesis of the etiology of TrPs implicating local myofascial tissue, the central nervous system, and mechanical factors is proposed in the 1999 edition of Travell and Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual.29 The hypothesis postulates that a central MTrP has multiple fibers with end plates releasing excessive acetylcholine and shows histopathologic evidence of regional sarcomere shortening. The positive-feedback loop of events perpetuates these changes until the loop is interrupted. The putative steps were elegantly explained by Simons.28 Evidence contributing to the etiology of TrPs has evolved from two early studies. Mense and Simons reported that histologic examination of biopsied muscle tissue in the vicinity of TrPs reveals large, rounded, and darkly stained muscle fibers, as well as increased muscle fiber diameters.30 At physical examination for MTrPs, these changes are manifested as taut bands and palpable nodules. An EMG study by Hubbard and Berkoff showed greater activity in MTrPs than in adjacent nontender muscle.31 EMG activity was significantly higher in TrPs of patients with chronic tension headaches than in normal patients and could be reduced by injection of sympathetic blockers such as phenoxybenzamine. In another study, McNutley and colleagues reported that EMG activity within an MTrP was significantly increased in subjects involved in an experimental stress test, whereas contiguous nontender muscle showed no changes.32 This finding may have implications for the psychophysiology of stress contributing to pain and the association with MTrPs.

Physical Examination and Mapping of Trigger Points

A distinguishing feature of MTrPs is their location within a taut band of muscle or fascia as identified by palpation. They can be discovered with a careful external and internal pelvic examination. Compression of the MTrP results in a twitch response, a transient contraction from the band of fibers, and referred sensory and motor responses (e.g., tenderness, pain) occurring distant to the TrP. Two objective methods have been used to document MTrPs. Algometry provides a quantitative measurement of pressure thresholds to document the sensitivity of TrPs. Results from several studies have confirmed that MTrPs are more sensitive than contralateral muscle areas without TrPs or surrounding healthy tissue.33,34 A difference in pressure threshold exceeding 20 newtons per square centimeter (2 kg/cm2) between a TrP and a contralateral point is considered abnormal.33 A second method, thermography, employs a noninvasive imaging technique to detect infrared radiation from body surfaces and heat distribution.35 Comparative imaging of subjects with clinical TrPs and asymptomatic controls revealed discrete thermal responses in muscles with suspected TrPs. Sensory referral areas for TrPs in symptomatic subjects showed significantly reduced temperatures from precompression levels during ischemic compression; no significant temperature changes were noted in asymptomatic areas after compression. It was assumed that the colder area was caused by a reduction in blood flow due to a sympathetic autonomic change associated with the myofascial pain syndrome.

A review of the neuroanatomy of the pelvis, such as that as provided by Wesselmann and colleagues, assists in understanding the pathophysiology of urogenital and rectal pain syndromes and their management.36 The involvement of MTrPs in CPP can thereby be taken in perspective. Travell and Simons published the first manuals on TrPs and myofascial pain and dysfunction and provided specific details of the pelvic muscles to check internally.16,22 A subsequent edition of this manual was published in 1998.12

Testing for MTrPs within the pelvis depends on the palpation skills of an experienced examiner, because no diagnostic standard has been established to identify intrapelvic MTrPs. The therapist must be trained in identifying TrPs and be able to feel for superficial and deep TrPs located in the belly and the attachments of the muscles. For the purpose of locating these MTrPs, the pelvic muscles can be grouped into three categories—perineal muscles, pelvic floor muscles, and pelvic wall muscles. Examination of intrapelvic muscles for MTrPs requires a vaginal or rectal approach, as appropriate for each muscle by establishing bony and ligamentous landmarks, and relating the direction of palpation to the direction of the muscle fibers. This was explained in detail by Travell and Simons, as was the relationship between symptoms and the location of associated MTrPs.12 Other MTrP associations have been gleaned from the experience of many physical therapists. Table 91-2 summarizes the internal pelvic muscles and external muscles referring pain to pelvis from MTrPs.

Table 91-2 Internal and External Muscles and Referred Pain to Pelvis from Myofascial Trigger Points

| Muscle | Referred Pain Site | Symptom |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic floor muscles | ||

| Levator ani | Sacrococcygeal region, perineal region | Pain in perineum, vagina, anal sphincter; pain with sitting; aggravated by lying on back and by defecation |

| Bulbospongiosus | Perineal region and adjacent urogenital structures | Pain in vagina, dyspareunia, perineal ache |

| Ischiocavernosus | ||

| Transverse perinei | ||

| Coccygeus | Sacrococcygeal region | Pain in coccyx, hip, or back; ischiococcygeus is likely cause of backache in late pregnancy and early labor |

| Sphincter ani | Poorly localized aching in anal region | Anal pain, painful bowel movement |

| Obturator internus | Perineal region, outward toward hip, whole pelvic floor, posterior thigh, and hamstrings | Pain in vagina, vulva, urethra, coccyx, posterior thigh; pain and feeling of fullness in rectum |

| Muscles referring pain into pelvis | ||

| Piriformis | Sacroiliac joint, hip girdle, hamstrings, pelvic floor, buttock, low back | Pain in rectum during defecation, dyspareunia; pain in referred areas worsens with palpation, standing, sitting, walking |

| Gluteus | Hip girdle, buttock, sacrum, hamstrings | Pain in low back, hip, inguinal area |

| Iliopsoas | Groin, anterior thigh, low back | Pain in groin, down anterior thigh, and in low back |

| Quadratus lumborum | Sacroiliac joint and buttock, lower abdomen, groin | Pain in low back and with coughing, sneezing, and walking |

| Abdominals | Entire abdomen up into ribs | |

| Transverse | Groin, inguinal ligament, detrusor, and urinary sphincter | Groin pain, bladder pain, urinary frequency or retention |

| Rectus | Across thoracolumbar back, xiphoid process, sacroiliac joints, and low back | Somatovisceral response, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, intestinal colic, dysmenorrhea |

| Pectineus | Groin area, bladder, and pubis | Pain in groin, bladder, urethra, and pubic area |

| Pyramidalis | ||

| Thoracolumbar | Abdomen | Visceral pain, sacral pain, pain in middle and lower back; pain can resemble renal colic |

| Paraspinals | ||

Approaches for Inactivating Myofascial Trigger Points

A variety of manual massage techniques have been reported to inactivate MTrPs.29 Manual therapy may involve active and passive rhythmic muscle releases based on the principle that tight or poorly relaxed muscles can exhibit released tension after moderate voluntary contraction. The active and passive release maneuvers take up the slack in the muscle by stretching it to the point of beginning resistance or discomfort. This is then followed by a patient-performed isometric contraction that is held in position by the patient or therapist.

Direct transrectal massage was reported by Thiele for patients with coccygodynia with pain localized to the coccyx and the presence of spasms of the levator ani and coccygeus muscles.14 A modified Thiele massage was used by Oyama and colleagues in 21 women to treat IC and high-tone dysfunction of the pelvic floor (e.g., dyspareunia, impaired bladder and bowl evacuation, pelvic pain exacerbated by physical activity or prolonged sitting).40 Subjects underwent 5 weeks of twice-weekly Thiele intravaginal massage, with massages of the affected hypertonic pelvic muscles, 10 to 15 times per session, from origin to insertion along the direction of muscle fibers. Additional short ischemic compression of tender points was applied as needed. IC symptom scores and pelvic floor muscle tone showed significant improvements, and pelvic tone remained improved at 4.5 months of followup in three of the four treated pelvic muscles, excepting the coccygeus.

Weiss reported amelioration of symptoms in 42 patients with urgency-frequency syndrome with or without urethral pain (and in some patients with IC) using manual therapy of discrete MTrPs in the pelvic floor.18 Treatment continued one to two times weekly for 8 to 12 weeks until MTrPs and muscle tension decreased. A program of home therapy involving muscle stretches and strengthening, biofeedback, and Kegel exercises was also part of the treatment. In the 42 patients (39 women, 3 men) with urgency-frequency syndrome, 83% had moderate to marked improvements or complete resolution. Of the 10 patients with IC (6 women, 4 men), 70% had moderate to marked improvements.

Injection with local anesthetics, saline, or water has been used for inactivation of MTrPs. An important sign of precise needle placement in an MTrP is elicitation of a local twitch response. The resulting MTrP inactivation should result in immediate relief of pain and tightness.24 Specific targeted therapy with local anesthetic injections of TrPs in the abdominal wall has been used for treatment of CPP in women.41,42 Slocumb reported that approximately 50% of 122 women with pelvic pain had relief after treatment that consisted of TrP blocks in all patients; additional surgeries were performed in 13 women.41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree