Chapter 50 FEMALE SEXUAL FUNCTION AND DYSFUNCTION

Why is there a chapter concerning women’s sexual function and dysfunction in a textbook entitled Female Urology? The answer should be obvious. Urologists and gynecologists who practice “female urology” will encounter women with sexual health concerns.1,2

A woman’s general health is a fundamental human right. If this is accepted, then urologic health and gynecologic health are fundamental human rights. If this is accepted, then sexual health should be a fundamental human right. If sexual health is a woman’s fundamental human right, then health care providers need to be educated on the fundamentals of women’s sexual health care delivery.3,4

SEXUAL HEALTH

According to the World Health Organization,3 sexual health “refers to a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being related to sexuality.” All women have the right to a “positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.” Moreover, “For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.”3

The World Association of Sexual Health has stated4 that women (and men) have the right to sexual equity—the freedom from all forms of discrimination regardless of sex, gender, sexual orientation, age, race, social class, religion, or physical and emotional disability.” Women (and men) also have the right to sexual pleasure—sexual pleasure is a source of physical, psychological, intellectual, and spiritual well-being.

What are the Barriers to Providing Women’s Sexual Health Care in the Female Urology Practice

Physicians in general and female urologists in particular face a challenge in finding the time and opportunity to discuss their women patient’s sexual health concerns, especially with the increasing and growing demands for other health care issues, including the significant financial pressures of providing “managed care.” Additionally, most physicians have limited training in the diagnosis and treatment of sexual health concerns. Currently, American medical schools devote on average less than 10 hours to sexual medicine education.5 Independent of the physicians, patients are also often unwilling or too uncomfortable to initiate a discussion about their own sexual problems.6

Sexual medicine issues are complex, and it is often difficult to separate psychological issues and interpersonal relationship concerns from biologic disorders.7 There are only limited evidence-based data available for diagnosis and management. Sexual health concerns are, in general, secondary to mind, body, and relationship issues that are interrelated in unique and individual ways and molded with distinct couple dynamics to cause the particular sexual problem.7 Psychological factors include previous sexual trauma and abuse, sexual neuroses, sexual inhibitions or idiosyncracies, and interpersonal relationship issues.8 Biologic factors may involve such pertinent aspects as aging; exposure to vascular risk factors; urologic conditions such as interstitial cystitis, previous radical cystecomy, and recurrent urinary tract infections; gynecologic conditions such as endometriosis, previous hysterectomy, childbirth, infertility issues, and sexually transmitted infections; inflammation; abnormal immunologic conditions; abnormal hormonal states (Figs. 50-1 and 50-2); tumors; mechanical compartment syndromes; blunt or penetrating traumatic injury; tissue weakness with organ prolapse; and others. Sexual health problems may also stem from the contribution of the male partner in women’s sexual health.1,7,8

Why Should Female Urology Practice Expand to Include Women’s Sexual Heath Care

Female urologists offer urogynecologic health care to women, and this should include comprehensive sexual health care. Over the last 30 years, urologic specialists have led the many advances realized in the biologic-based knowledge in sexual medicine.9 Furthermore, urologists have revolutionized the therapeutic armamentarium for contemporary management of biologic-focused men’s sexual health care.9 Practically, female urologists are in a unique position to understand that female peripheral sexual organs are an essential component of the anatomy and physiology of the peripheral genitalia and pelvic floor constituents.

Many population-based studies have revealed a high prevalence of sexual health concerns in women of all ages.2,8,10–15 A woman’s sexual problems can cause significant personal distress in approximately 25% of those with sexual health concerns, including a diminution of self-worth and self-esteem, a reduction in life satisfaction, and a decline in the quality of her relationship with her partner.10–15 Many investigations have shown that a satisfying sex life is important to most women throughout most of their lives.16 As life expectancy increases, there are increasing numbers of aging women.17 Sexual health concerns are more common among aging women than among younger women.10–15 The number of postmenopausal women worldwide in the year 2000 was 569 million; that number is projected to grow to 967 million by 2020 and to 1.2 billion by 2030.17 As a result of the controversy concerning hormone therapy that followed the release of the Women’s Health Initiative findings in 200218 millions of menopausal women altered and or discontinued hormone therapy practices, and this directly influenced many women’s subsequent vaginal physiology and sexual interest states.19 As the decline in estrogen production begins in transition to menopause, sexual dysfunction becomes common, often interfering with women’s interest in, and satisfaction with, sexual activity.

It is important to note the existence of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), an international, multidisciplinary, academic, clinical, and scientific organization. The purposes of ISSWSH are to provide opportunities for communication among scholars, researchers, and practitioners about women’s sexual health; to support the highest standards of ethics and professionalism in research, education, and clinical practice relative to women’s sexual health; and to provide the public with accurate information about women’s sexual health. Interested health care professionals should visit the organization’s web site, (http://www.isswsh.org) for more information. More detailed information about ISSWSH and the management of women’s sexual health concerns may be found in the multidisciplinary textbook written primarily by ISSWSH members entitled, Women’s Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment.20

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

There are limited population-based epidemiologic studies of women with sexual health concerns.2,8,10–15 Based on current published information, the following is the most contemporary, internationally consensed classification system.21

Laumann and associates, in a U.S. population-based study of more than 1700 women, observed that more than 40% reported sexual health concerns.15 In that investigation, the most common sexual health concern was lack of sexual desire, followed by inability to achieve orgasm, lack of pleasure from sex, and pain during sex. Poor health, emotional problems or stress, decline in social status, and having ever been forced sexually were among the factors associated with low desire, arousal disorder, and sexual pain. A worldwide survey of more than 27,000 men and women aged 40 to 80 years assessed the relevance of sex and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.22 In that survey, women’s sexual health concerns were classified into five subcategories: lack of interest in sex, inability to achieve orgasm, lubrication difficulties (dryness), sex not pleasurable, and pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia). The percentage of women who reported having at least one sexual health concern on a frequent or persistent basis was 39%. The percentage of women who reported having only one of the five sexual health concerns ranged from 10% for “dyspareunia” to 21% for “lack of interest in sex.”8,22

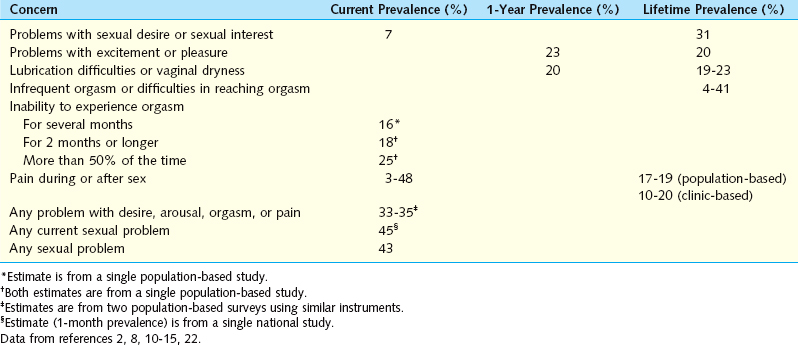

Contemporary international prevalence data concerning women’s sexual health problems, are represented in Table 50-1.2,8,10–15,22

Table 50-1 Estimated International Prevalence of Women’s Sexual Health Concerns from Various Studies

The Continuum Hypothesis for Women’s Sexual Health Concerns

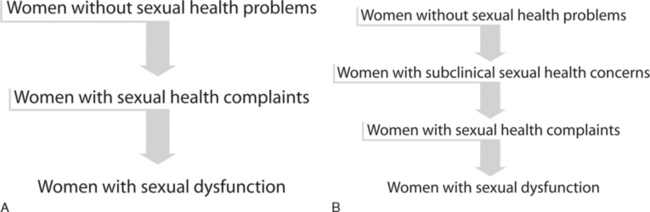

One hypothesis is that women without the condition first develop an intermediate stage involving complaints of problems with sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, sensation, orgasm, and pain without any accompanying personal distress.23 The pathophysiology is most likely multifactorial and may be secondary to medical conditions such as hormonal milieu changes or vascular disease; psychological conditions such as depression; medications that may contribute to symptoms, such selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and antipsychotics; or any other social or relationship issues that may play a role, such as a history of sexual abuse or partner-related issues. Ultimately, when personal distress results as a consequence of the persistence or intensity of the sexual symptoms, the problem is considered to have evolved into frank sexual dysfunction (Fig. 50-3A).23,24

Consistent with the hypothesis that sexual health concerns exist in a continuum, one may then introduce the additional concept of an earlier intermediate stage. The idea of a subclinical stage of women’s sexual health concerns, one that occurs before the onset of overt symptoms but is recognized clinically by abnormal questionnaire results and/or laboratory values, comes from recent prospective, multi-institutional studies.25,26 With the goal of defining androgen levels in a premenopausal population, prospective candidates underwent an initial interview to identify those “free of sexual health problems.” Women who met inclusion and exclusion criteria subsequently underwent determination of androgen levels and completion of a validated sexual function questionnaire on which low scores indicated poor sexual function. A subgroup of women from that study, who perceived themselves as having no deficits in sexual function and presented to take part in the study as the control population, were found to have scores on the validated sexual function questionnaire consistent with sexual health problems. These abnormal findings precluded their inclusion in the control group. We subsequently attempted to better characterize the women in this group by recording androgen levels. In these asymptomatic women with low validated sexual function questionnaire scores, androgen levels were found to be virtually indistinguishable from those of women with symptomatic sexual dysfunction and significantly lower than those of women who denied sexual concerns and scored higher on the validated sexual function questionnaire.

The concept of a subclinical stage of a medical condition is well established in the literature. For example, subclinical hypothyroidism27 is considered to exist when there is an abnormally elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone level in a patient who has not yet manifested obvious or evident symptoms of hypothyroidism (e.g., fatigue, depression, osteoporosis, weight gain). Other scenarios of subclinical medical conditions are well described, such as impaired glucose tolerance, elevated liver function tests,28 or abnormal electrocardiogram associated with early coronary atherosclerosis.29 The term subclinical refers to those situations in which abnormal testing or laboratory values may be a harbinger that precedes overt symptoms of the condition.

There is a previously undefined population of women who claim an absence of sexual health problems on initial clinical interview but who are found to have validated psychometric questionnaire scores consistent with the presence of sexual health concerns and androgen levels comparable to those seen with androgen insufficiency. It is hypothesized that the development and progression of women’s sexual health problems follows a continuum. In this continuum hypothesis, women without sexual health complaints may progress first through a subclinical stage, followed by a symptomatic stage, and subsequently develop frank sexual dysfunction when the sexual problem becomes clinically meaningful and is associated with personal distress (see Fig. 50-3B). Future research studies are needed to assess the relevance of these intermediate stages of women’s sexual health, in general, and the subclinical state of female sexual dysfunction, specifically. In particular, it would be of interest to investigate the role of any prophylactic management strategies, psychological and biologic, that may halt the development of future overt clinical symptoms and/or frank sexual dysfunction.

PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Effect of the Male Partner who has Erectile Dysfunction

Couples share their sexual dysfunctions. Women with men who have ED may have their own sexual function adversely affected. What are the scientific data available concerning changes in sexual function among those women whose partners have ED? Blumel and colleagues examined a sample of 534 otherwise healthy women who had ceased sexual activity with their male partners. It was noted that, in the cohort younger than 45 years of age, ED was the most frequently cited reason for cessation of the woman’s sexual activity.30

Initial studies were, however, obtained with data from the man’s perspective. Past research in this area involved inquiries addressed to men with ED about the effect of their sexual problem on their women partners. One study showed significant improvement in the marital interaction score when men with ED used a selective PDE5 inhibitor.31

Contemporary research has finally begun to address the issue from the woman’s perspective. Data from several investigations are derived from the woman herself, as her own study subject. Cayan and colleagues performed a prospective study assessing the sexual function of women with men who had ED.32 The study involved 38 such women, as well as a control group of 49 women whose male partner did not have ED. Women’s sexual functions, including sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain, and total score, were significantly diminished among women with men who had ED. Among those women whose male partners received treatment (penile prosthesis insertion, oral PDE5 inhibitor treatment) for their ED, significant improvements in sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain in the women were identified.

Montorsi and Althof investigated thoughts and views on intercourse satisfaction in 930 women whose male partners were taking a selective PDE5 inhibitor to manage ED.33 These women had significantly higher intercourse satisfaction than did women whose men were using a placebo.

Chevret and coworkers developed and validated the Index of Sexual Life to measure sexual function of women in relationships with men with ED.34 Such women were found to have significantly diminished sexual drive and sexual satisfaction compared to women whose male partners did not have ED.

Oberg and colleagues examined data from a nationally representative Swedish cross-sectional population investigation of sexual life, attitudes, and behavior.11 A total of 926 women, aged 18 to 65 years, were sexually active in a steady heterosexual relationship during the 12 months before the investigation. Data from women who claimed personally distressing sexual dysfunctions quite often, almost all the time, or all the time were compared with data from women who had no sexually dysfunctional distress. Women reporting distress due to low sexual interest or orgasmic dysfunction were very likely to have a partner with an ED (odds ratios, 47.6 and 20.0, respectively).

In the Female Experience of Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality study,35 data were analyzed from 283 women in eight countries whose male partners had ED. They were asked questions comparing their sexual activity, sexual function, and beliefs about sexuality before and since their partner had experienced difficulties with erection. Data were stratified by the man’s self-reported degree of ED (mild, moderate, or severe). Women whose partners had ED reported a lower frequency of sexual activity currently, compared with before their partner developed erectile difficulties. Significantly fewer women reported that they experienced sexual desire, sexual arousal, orgasm, or sexual satisfaction (“almost always” or “most times”) currently, compared with before their partner developed erectile difficulties. There was a significant correlation between the reduction in the woman’s frequency of orgasm, and her reduction in sexual satisfaction, and the degree of her partner’s self-reported ED. Women had the lowest frequency of orgasm and the lowest satisfaction with the sexual experience when their partners had severe ED.

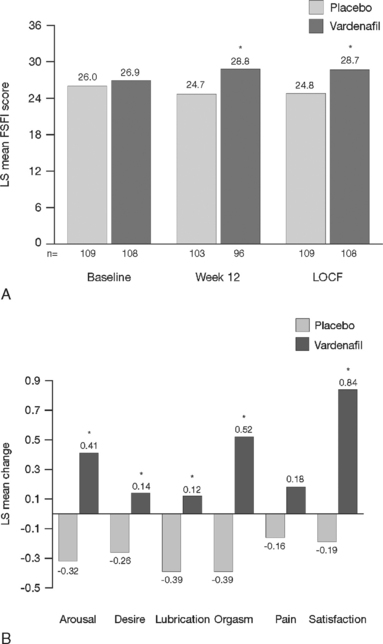

Scientific data were obtained from a double-blind, multicenter, 3-month, randomized trial involving men with ED who had been in a stable heterosexual couple relationship for at least 6 months.36,37 In this trial, women whose male partner had ED were asked at initial screening to complete the validated Female Sexual Function Inventory. Significant improvement in the woman’s sexual function and sexual satisfaction were observed after their partner was treated with a selective PDE5 inhibitor, vardenafil (Fig. 50-4) versus placebo.

Effect of the Male Partner Who Has Premature Ejaculation

Because premature ejaculation is the most common male sexual dysfunction, affecting approximately 25% of men, it is likely that many women will experience a sexual relationship with a man with premature ejaculation.38 Premature ejaculation is objectively determined using a stopwatch to record intravaginal ejaculatory latency time, defined as the time between vaginal intromission and intravaginal ejaculation. It has been suggested that an intravaginal ejaculatory latency time of 2 minutes or less may serve as a criterion for defining premature ejaculation.39

Women with men who have premature ejaculation may have significant distress, interpersonal difficulties, and dissatisfaction with sexual intercourse.40 The woman’s distress is a common reason for the man to consult a clinician about premature ejaculation.

Byers and Grenier investigated the effect of premature ejaculation on the sexual function of 152 couples.41 Concerning the couple’s perceptions of whether the premature ejaculation was a problem, reports of women and men were only moderately correlated. For both the women and the men, having more premature ejaculation characteristics was related to lower sexual satisfaction. The results suggested that, for most couples, the premature or early timing of ejaculation adversely affects sexual satisfaction.

Patrick and colleagues40 carefully selected patients with and without premature ejaculation based on stopwatch testing. The mean intravaginal ejaculatory latency time was 1.8 minutes in the 207 men with premature ejaculation. This was significantly lower than the time (7.3 minutes) in the 1380 men without premature ejaculation. Women whose male partner had premature ejaculation had significantly decreased satisfaction with sexual intercourse and significiantly increased interpersonal difficulty and distress, compared to women whose partner did not have premature ejaculation (P < .0001). They also reported “poor” or “very poor” satisfaction with sexual intercourse (28% versus 2%) and gave worse ratings (“quite a bit” or “extremely”) for personal distress (44% versus 3%) and interpersonal difficulty (25% versus 2%), compared to women whose partner did not have premature ejaculation (P < .0001).

Changes in the Female Genitalia with Aging

The structure and function of a woman’s genitalia are highly dependent on the sex steroid hormonal milieu.1,19,42–46 As a woman ages or a young woman is exposed to medicines that interfere with the hormonal milieu (e.g., oral contraceptives, tamoxifene), her supply of sex steroid hormones (estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone) diminishes significantly.1,19

Estrogens and androgens are required for genital tissue structure and function.19 These hormones act on estrogen and androgen receptors, respectively, which exist in high numbers in genital tissues, including the epithelial/endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells of the vagina, vulva, vestibule, labia, and urethra. Diminished estrogen production for natural or iatrogenic reasons renders women’s genital tissues highly susceptible to atrophy (see Figs. 50-1 and 50-2). Physical examination7,47 of the postmenopausal woman’s genitalia shows clitoral atrophy, phimosis, and nearly absent labia minora (Fig. 50-5). The appearance of a woman’s labia minora mirrors her level of estradiol, because these labia are exquisitely sensitive to estradiol. The urogenital area termed the vestibule is very important in female sexual function because it contains organs that are sensitive to both estrogen and androgen. For example, the clitoral tissues and prepuce are androgen sensitive. The minor vestibular glands (Fig. 50-6), which are located in the labial-hymenal junction, are embryologically derived from the glands of Littre, which are also androgen dependent. The glands of Littre are located on the anterior surface of the urethra.

A host of structural changes and cellular dysfunctions occur in women’s genital tissues as a result of estrogen deficiency.7,48–51 For example, estrogen deficiency specifically in the vagina leads to vaginal atrophy. One consequence is an alteration in the normally acidic vaginal pH that discourages the growth of pathogenic bacteria. The change to an alkaline pH value in the atrophic vagina leads to a shift in the vaginal flora, increasing the likelihood of discharge and odor. In an estrogen-rich environment, glycogen from sloughed epithelial cells is hydrolyzed into glucose and then metabolized to lactic acid by normal vaginal flora. In postmenopausal women, however, epithelial thinning reduces the available glycogen.

In addition to vaginal atrophy and a reduction in organ size, other signs of a decline in sex hormones in women include vaginal dryness, absent secretions or lubrication, pale or inflamed tissue, petechiae, epithelial/mucosal thinning, organ prolapse, changes in external genitalia, decreased tissue elasticity, and loss of smooth muscle. Symptoms of women’s sexual health concerns that the clinician may elicit when taking a history in a menopausal woman are include dyspareunia, vaginismus, coital anorgasmia, vaginal and/or urinary tract infections (pH imbalance), and overactive bladder/incontinence.7,48–52

Effects of Sex Steroid Hormones on the Vagina

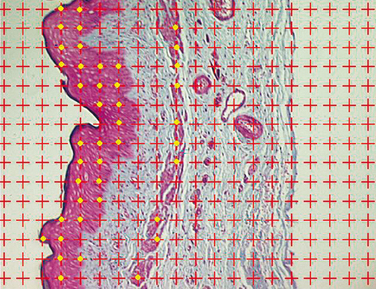

The human vagina consists of three layers of tissue: the epithelium (composed of squamous cells), the lamina propria, and the muscularis (inner circular and outer longitudinal smooth muscle). The epithelium undergoes mild changes during the menstrual cycle. The lamina propria is replete with tiny blood vessels that become engorged with blood during sexual arousal, leading to lubrication. The smooth muscle of the muscularis enables the vagina to dilate and lengthen during penile penetration. Relaxation of that muscle leads to arousal. These three layers of tissue may function in an interrelated way (Fig. 50-7). It is hypothesized that the blood vessels in the lamina propria that allow for lubrication are dependent on growth factors, and that the growth factors are derived from the muscularis. Postmenopausal atrophy of vaginal tissues may be caused by decreased synthesis these growth factors that results in diminished number of critical blood vessels in the lamina propria.

Controlled studies employing a rat model of vaginal atrophy demonstrated the effects of various dosages of estrogen, progestin, testosterone, and combinations of these hormones on physiologic and anatomic outcome parameters.52 These measures included organ wet weight, vaginal blood flow, epithelial height, muscularis thickness, and vaginal innervation. In each study, the effects on the vagina of of the hormones being tested were compared between rats that had undergone sham ovariectomies and rats that had actually had both ovaries removed. The hormones (or saline) were delivered through a pump inserted into the back of the neck of each animal. A Doppler probe inserted into the vagina was used to record blood flow after electrical stimulation of a nerve next to the vagina. All animals were then killed, and vaginal tissue was removed for biochemical or histologic studies. Removal of the ovaries was found to reduce the wet weight of the uterus, which rose again with administration of estrogen, because the uterus is a very estrogen-sensitive organ, much more so than the vagina.

Increased vaginal blood flow is an indicator of sexual arousal. Genital swelling and lubrication are responses to increased clitoral and vaginal perfusion; increased length and diameter of the vaginal canal and clitoral corpora cavernosa; engorgement of the vagina wall, clitoris, labia majora, and labia minora; and transudation of lubricating fluid from the vaginal epithelium. In the animal studies just described, blood flow to the vagina was greatly reduced in the oophorectomized rats compared with the intact rats. Contrary to what one might expect, subphysiologic doses of estradiol increased vaginal blood flow in oophorectomized rats more than either physiologic or supraphysiologic doses.52 Ovariectomy deprived the rats of estradiol, causing the vaginal epithelium to thin down to a single layer. Subphysiologic doses of estradiol increased the thickness of the vaginal epithelium most, because the oophorectomized rats had more estrogen ERα receptors in the epithelium than the intact animals did. A small amount of estradiol delivered to tissue with many estrogen ERα receptors produced a huge response. Thus, estradiol regulates estrogen receptors through a negative feedback system. The more estradiol that is available, the fewer estrogen receptors there are. The muscularis, the muscle that enables the vagina to lengthen and widen during sexual arousal, also atrophies without estrogen. In postmenopausal women who do not take hormone therapy, the vaginal epithelium, lamina propria blood vessels, and muscularis all decrease. Like the epithelium, the muscularis responds to estradiol by increasing in thickness.52