Fig. 27.1

Port placement alternatives for emergent colorectal surgery

Indications

Colorectal Perforation

Acute Colonoscopic Perforation

Laparoscopic intervention can be a suitable approach for both acute and delayed colonoscopic perforations. The procedure depends on the degree and cause of perforation, timing following the event, degree of peritoneal contamination, and overall clinical condition of the patient. Nearly all cases can be managed laparoscopically, whether primarily repairing the perforation or resecting with or without ostomy creation.

Procedure Steps

Abdominal entry: left upper quadrant port placement under direct visualization.

Exploration: the abdominal and pelvic cavities are explored to assess the location, extent of injury, and presence of fluid or fecal contamination. If fecal contamination is encountered, conversion to hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery or laparotomy for lavage, bowel resection, and fecal diversion is recommended. Fecal washout cannot often be adequately performed with pure laparoscopic techniques. However, if minimal contamination is recognized, the bowel injury can often be primarily repaired. The entirety of the large bowel is examined to identify the perforation. Intraoperative colonoscopic assistance utilizing carbon dioxide may be required to aid visualization of the perforation. Once identified, proximal bowel clamping is performed to avoid further contamination.

Laparoscopic management alternatives:

(a)

Laparoscopic colorrhaphy (Video 27.2): the perforation borders are defined and debrided if devitalized tissue is encountered. The repair is achieved with a one-layer colorrhaphy with absorbable suture (Fig. 27.2). The use of multiple layer colorrhaphy may potentially result in lumen narrowing, especially in the sigmoid colon. Following the repair, an air insufflation test and direct intraluminal visualization of the perforation site should be performed to confirm the integrity of the repair. Injuries extending into the mesentery may be more challenging to repair, and care must be taken to identify the entire extent of the perforation. The borders of the mesentery, which often bleed, may obscure the view and lead to failure to recognize and address the entire extent of the perforation.

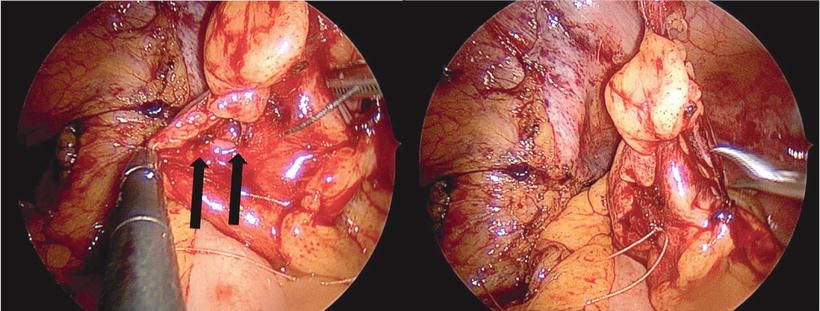

Fig. 27.2

Intraoperative view of a colonic perforation following colonoscopy (arrows). The perforation was successfully repaired with single-layer primary colorrhaphy

(b)

Segmental resection: after visualizing the perforation, if primary repair is not appropriate, laparoscopic segmental colectomy may be performed with or without ostomy creation. The same principles of laparoscopy in the elective setting are followed and often a medial-to-lateral approach is favored to avoid the inflamed bowel with associated adhesions and friable tissue.

(c)

Bowel diversion: in extreme cases, proximal diversion with colonic lavage may be a temporary measure. Concomitant diversion is also considered following (a) or (b) above, under the discretion and judgment of the surgeon at the time of the operation.

Acute Perforated Diverticulitis

The management of acute perforated diverticulitis varies depending on the clinical presentation of the patient and must be approached on an individual basis. Those who require emergent intervention typically present with free perforation, with an intra-abdominal abscess and/or peritonitis. Laparoscopic surgery in this setting can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. The therapeutic measures can include drainage of abscesses, lavage, primary closure of perforation, resection, and/or diversion. Although, it has been generally agreed that the presence of fecal peritonitis requires an open lavage, we have been successful using hand-assisted technique to effectively evacuate the contamination while maintaining a minimally invasive platform.

Procedure Steps

Abdominal entry: left upper quadrant optical trocar port placement under direct visualization.

Abdominopelvic exploration: often, the omentum is inflamed and adhered to the peritoneal lining and pelvis requiring mobilization to explore the abdomen. The peritoneal cavity is then thoroughly examined to evaluate the nature of the contamination. For patients with Hinchey 3 (purulent peritonitis), we perform laparoscopic lavage with or without over-sewing the bowel wall with placement of drains through the port sites. It is important to evaluate for inter-loop abscesses, which may be a case for treatment failure if not identified and adequately drained during the procedure. It is also important to locate the perforation site itself, as an occult abscess may be present at or adjacent to this area, which is often shielded by inflamed tissue (Video 27.3). For those presenting with Hinchey 4 (fecal peritonitis), we typically perform hand-assisted laparoscopic technique, which allows evacuation of the fecal content as well as sigmoid resection with colostomy. A 5–7 cm umbilical or Pfannenstiel incision can be used to place the hand assist device. However, if this technique does not afford complete evacuations of the fecal contents, an open laparotomy is required.

Lavage: it is necessary to lavage all four quadrants including perihepatic, perisplenic, right and left gutters, and pelvis (Video 27.3). Often occult fluid collections are identified and attended to in this process. Although no standard volume of irrigation has been reported, we recommend lavage until the fluid return is clear. The laparoscopic lavage is an excellent device to episode jet irrigation and allows litters of heated fluid to be utilized in an expeditious fashion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree