Chapter 48 Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas

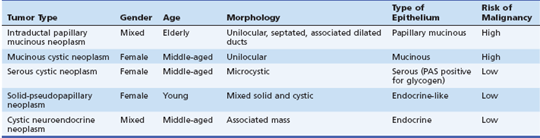

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are traditionally organized by the type of lining epithelium since this feature dominates the risk of malignancy and management (Table 48.1).1 Mucinous lesions include intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs). The nonmucinous lesions include serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs), solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs), cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms, and other rare lesions.

Prevalence

The prevalence of pancreatic cysts has been examined through autopsy examinations of the pancreas in adults without known pancreatic disease. The prevalence of pancreatic cysts found at autopsy in Japan was approximately 73 of 300 cases (24.3%).2 The prevalence of cysts increased with increasing age of the patient. The cysts were located throughout the pancreatic parenchyma and were not related to chronic pancreatitis. The epithelium of the cysts displayed a spectrum of neoplastic change, including atypical hyperplasia (16.4%) to carcinoma in situ (3.4%). The malignancy simulated pancreatic adenocarcinoma and arose from the epithelium lining the cyst.

The prevalence of pancreatic cysts in the United States has been estimated in patients undergoing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for a variety of medical problems.3 This study revealed that approximately 15% to 20% of 1444 patients had at least one pancreatic cyst. Older patients are more likely to have a cyst than younger patients. Screening abdominal ultrasound in a younger population revealed that 0.21% of 130,951 adults had a pancreatic cystic lesion.4

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Clinical Epidemiology

IPMNs are intraductal grossly visible (≥1.0 cm) epithelial neoplasms of mucin-producing cells, arising in the pancreatic ductal system (main duct and/or branch duct).5 Their true incidence is uncertain but estimates range from 1% to 3% of neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas and 20% to 50% of all pancreatic cystic neoplasms.1,5–8 IPMNs affect men and women equally or men predominantly, depending on the reported series, and they tend to occur in an older age group than MCNs.5

MCNs account for 10% to 45% of pancreatic cystic neoplasms.1 Women are affected far more commonly than men (20:1 ratio),9 with a mean age at diagnosis in the fifth decade.1

SCNs have been estimated to account for about 25% of all cystic neoplasms of the pancreas10 and for 1% to 2% of pancreatic neoplasms.11 SCNs occur only in adults with a median age in the sixth or seventh decade. The majority of patients with SCNs are female. Traditionally about half of the tumors are discovered as incidental findings during abdominal imaging or surgery or at autopsy.6,12 Malignant SCNs (i.e., serous cystadenocarcinomas) are extremely rare; only about 25 cases have been reported to date.11

SPNs are reported to account for 0.9% to 2.7% of all neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas. They occur predominantly in women.13 The mean age at diagnosis is in the twenties or thirties, depending on reports.14,15

Cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas are rare, accounting for less than 10% of all pancreatic cystic neoplasms.1,16 In large series, the age at diagnosis is between 50 and 60 years, with both sexes affected nearly equally.17,18 It is rare for cystic endocrine tumors to produce sufficient hormones to be clinically active.17,19 Cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms may be seen in association with von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) syndrome.20 Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 may be present in up to 21% of patients with cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms.17

Risk Factors for Cystic Lesions

In the vast majority of patients with a cystic lesion, no risk factor is apparent. VHL syndrome is the best-described inherited disorder associated with pancreatic cystic lesions. In the largest series to date, pancreatic involvement was observed in 122 of 158 patients (77.2%) and included true cysts (91.1%), serous cystadenomas (12.3%), neuroendocrine tumors (12.3%), or combined lesions (11.5%).21

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is poorly understood. The prevalence of activating point mutations in codon 12 of the KRAS oncogene in IPMN and MCN is reported to increase with the increasing degree of dysplasia.5,9 Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the P16 gene was observed with increasing degrees of histologic atypia in IPMN, whereas LOH of the P53 gene was seen only in invasive carcinomas.22 In one report, 65% of cases had a KRAS mutation that showed a single pattern without evidence of a multiple or heterogeneous pattern. Furthermore, the distribution of LOH in 9p21 (P16) and 17p13 (P53) of IPMN lesions was related to grade of dysplasia. LOH in 9p21 (P16) was present in 12.5% of adenomas and 75% of carcinomas; LOH in 17p13 (P53) was observed only in invasive carcinomas. These results may indicate that LOH in 9p21 (P16) is an early genetic event whereas LOH in 17p13 (P53) is a later genetic event, suggesting a clonal progression for the development of IPMN.23

The pathogenesis of SCNs is likely to be very different compared to MCNs and IPMNs. KRAS mutations are present in IPMNs24 and MCNs25 but not in SCNs.26 In addition, LOH at 3p25, the chromosomal location of the VHL gene, was present in 57% (8 of 14) of serous microcystic adenomas compared with 17% (2 of 12) of MCNs in one study.25

SCNs are strongly associated with mutations of the VHL gene located on chromosome 3p25.26,27 The VHL gene is likely to play an important role in the pathogenesis of SCNs. In one study, 70% of the sporadic SCNs studied demonstrated LOH at 3p25 with a VHL gene mutation in the remaining allele.28 The mutations in the VHL gene probably most commonly affect the centroacinar cell and result in hamartomatous proliferation of these small cuboidal cells. The expression of keratin in clear epithelial cells resembles that in ductal and/or centroacinar cells and is most likely responsible for the fibrocollagenous stroma.29

Pathology

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms

IPMNs are similar to MCNs in that they are cystic neoplasms that secrete mucin. However, IPMNs are characterized by a unique papillary epithelium and arise from ductal epithelium. Depending on the pancreatic ductal system involved, IPMNs are classified as main-duct type IPMN, branch-duct type IPMN, or combined-type IPMN.30 The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification separates IPMNs according to grade of dysplasia: IPMN with low- or intermediate-grade dysplasia, IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, and IPMN with an associated invasive carcinoma. The presence of a papillary neoplasm and obstructing mucus causes the pancreatic duct to dilate.5 The degree of ductal ectasia produced varies with the degree of mucin production, but duct dilation great enough to be seen on imaging studies or gross pathologic examination is a diagnostic feature. Mucin production may be so excessive that mucin will be spontaneously secreted out of the ampulla.31 The degree of dysplasia exhibited by the epithelium may range from low grade to intermediate grade to high grade (carcinoma in situ) and the foci of early malignancy may be evident by the presence of mural nodules.32 The solid malignancies that arise from IPMN are more likely to have papillary features, as compared to typical pancreatic malignancies that arise from the main pancreatic duct.33

Four subtypes of IPMNs based on the predominant architectural and epithelial cell differentiation have been documented: gastric, intestinal, pancreatobiliary, and oncocytic.34 The four subtypes were reported to be associated with significant differences in survival. Patients with gastric-type IPMN had the best prognosis; those with pancreatobiliary-type IPMN had the worst prognosis.35

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms

MCNs (Fig. 48.1) are composed of discrete individual locules that vary in diameter. MCNs are lined by mucin-producing cells in a columnar epithelium. They usually do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system. The 2010 WHO classification separates MCNs based on the degree of epithelial dysplasia: MCN with low- or intermediate-grade dysplasia, MCN with high-grade dysplasia, and MCN with an associated invasive carcinoma.9 The degree of atypia of the tumor is classified according to the most advanced degree of dysplasia/carcinoma present.

MCNs often contain a unique highly cellular (so-called “ovarian-type”) stroma that often contains estrogen and progesterone receptors. It occurs almost exclusively in female patients, although rare cases of MCNs with ovarian stroma in male patients have been encountered. Many authorities have restricted the definition of MCNs to include only those cystic mucinous tumors that contain ovarian-type stroma.36 The cyst fluid from MCNs is often viscous and clear.

Serous Cystic Neoplasms

SCNs (Fig. 48.2) are benign, solitary, cystic tumors that arise from centroacinar cells. They are composed of cuboidal glycogen-rich epithelial cells. According to the degree of dysplasia, they are classified as serous cystadenoma or serous cystadenocarcinoma. As stated earlier, serous cystadenocarcinomas are rare.11 Although the majority of serous cystadenomas are microcystic, there are four histologic variants: macrocystic serous cystadenoma, solid serous adenoma, VHL-associated serous cystic neoplasm, and mixed serous neuroendocrine neoplasm.11 The classical “microcystic” serous cystadenomas are composed of multiple small thin-walled cysts with a honeycomb-like appearance on cross-section. Microcystic serous cystadenomas may grow to a large diameter over the long term and the large lesions often have a fibrotic or calcified central scar. Macrocystic serous cystadenomas are composed of far fewer cysts and the diameter of each cyst varies from microcystic to large cavities.37 The presence of discrete, large cystic cavities mimics the appearance of mucinous lesions. However, the cyst fluid from serous cystadenomas is nonviscous and may contain blood as a result of the vascular nature of the lesions.38 Despite the solid gross appearance, solid serous adenomas share the cytologic and immunohistologic features of classic SCN. VHL-associated SCN describes multiple SCNs that affect patients with VHL syndrome. The mixed serous neuroendocrine neoplasms are rare, highly suggestive of VHL syndrome.11

SCNs contain a prominent fibrous stroma, glycogen-rich epithelial cells, and endothelial and smooth muscle cells.27 Ultrastructurally, fibrocollagenous stroma is composed of myofibroblasts and endothelial cells embedded in thick collagen bundles. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are not present.29

Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasms

SPNs are low-grade malignant neoplasms composed of poorly cohesive monomorphic epithelial cells that form solid and pseudopapillary structures. SPNs frequently undergo hemorrhagic-cystic degeneration.13

SPNs form large, round, single masses. Macroscopically, cross-section shows solid areas and zones of mixture of hemorrhage, necrosis, and cystic degeneration. Microscopically they are a combination of solid, pseudopapillary components and hemorrhagic-necrotic, pseudocystic components. When the poorly cohesive neoplastic cells fall out, the remaining cells and the stroma form the pseudopapillae. Mucin is absent.13

Cystic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

Cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms are composed of neuroendocrine tissue. Although a mild cystic change is common in solid pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, marked cystic alteration is rare. They may be unilocular or multilocular. The cyst portion contains clear serosanguineous fluid.39 The pathophysiology of cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms is controversial. Infarction and necrosis, hemorrhage, and malignant degeneration in a pseudocyst have been suggested.19,40 Some advocate that cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms are a different tumor type from solid counterparts.17 The classic cystic neuroendocrine neoplasm is populated with a characteristic small, granular population of cells that are stainable for immunoreactive hormones, chromogranin, and synaptophysin.17,40

Clinical Presentation

Most patients with a pancreatic cystic lesion have nonspecific symptoms. The cystic lesion is usually found with computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography (US) imaging performed for the evaluation of another condition. When symptoms are present, the most common presentation is recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting as a result of mild pancreatitis. Cystic lesions that cause duct compression or involvement of the main pancreatic duct are prone to cause pancreatitis.1 Chronic abdominal pain and jaundice are rare presentations of a cystic lesion and suggest a malignancy or a pseudocyst. Patients with a cystic malignancy will present with symptoms and signs similar to pancreatic cancer (i.e., pain, weight loss, and jaundice).41 Pseudocysts may arise after an episode of acute pancreatitis or insidiously in the setting of chronic pancreatitis and are associated with chronic abdominal pain. It is common for cystic lesions associated with pancreatitis to be diagnosed as pseudocysts and be confused with cystic neoplasms that also cause pancreatitis.42

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a cystic lesion of the pancreas is very wide and often causes confusion. Since the treatment of a pseudocyst and cystic neoplasm are so different, it is incumbent on the clinician to first differentiate between these major categories of lesions. Although it is unusual for a patient with a pseudocyst to present without preceding symptoms, it may occur in mild chronic pancreatitis. Evidence of inflammatory changes or calcifications in the pancreas is suggestive of a pancreatic pseudocyst. However, in the initial setting of mild pancreatitis it may be difficult to differentiate between a cystic neoplasm that has caused pancreatitis and a small pseudocyst that has formed as a result of pancreatitis.43 If a cystic lesion has been present for many years, it is highly likely that the lesion represents a cystic neoplasm. Congenital cysts of the pancreas are rare.44

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree