Chapter 43 Choledocholithiasis

Gallstone disease is a common condition. It is estimated that in the United States between 500,000 and 700,000 cholecystectomies are performed per year. In a U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 14,228 participants between the ages of 20 and 74 underwent gallbladder ultrasonography. The prevalence of gallstones was 7.1% and the cholecystectomy rate was 5.3%.1 However, the true prevalence in the general population is probably higher if more elderly subjects are included.

The prevalence of bile duct stones is less well defined. In Western countries bile duct stones typically originate from the gallbladder. These stones are often mixed or cholesterol stones. In the East, stones often arise de novo within the bile duct. These are brown in color, soft, and muddy pigmented stones. The mechanism of primary stones is bile duct infection and stasis. Approximately 10% to 15% of patients with gallbladder stones develop adverse events of biliary colic, cholangitis, or pancreatitis, with some overlap among these clinical presentations. In surgical series of cholecystectomy for uncomplicated gallstone disease, the incidence of bile duct stones is less than 5%,2 though the proportion of bile duct stones can be as high as 47% in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis who undergo early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).3 Those with acute cholangitis are expected to have a high rate of bile duct stones as well.

The natural history of bile duct stones is not well understood. In a study4 that compared findings of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and subsequent ERCP, 21% of 92 patients with bile duct stones on EUS had passed them within 1 month. Stone size <5 mm was an independent predictive factor of passage. In another study2 Collins et al. performed sequential cholangiography using a transcystic catheter placed at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The rate of bile duct stones in patients on cholangiography was 3.4%. In more than one third of cases, calculi passed spontaneously at 6 weeks. Smaller stones may therefore pass spontaneously into the duodenum without causing symptoms. On the other hand, stone passage through the ampulla of Vater may cause bile reflux into the pancreatic duct with resultant acute pancreatitis. Larger stones can also be impacted at the distal bile duct causing biliary colic and cholangitis. Chronic obstruction, though uncommonly due to stones, can lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension. In general, these adverse events are serious and can be life threatening. Patients with suspected bile duct stones should therefore be investigated and if stones are identified, these should be extracted.

Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Choledocholithiasis

Initial investigations in someone suspected to have bile duct stones should include liver biochemical tests and transabdominal ultrasonography (TUS) (see Chapter 33).

TUS has a sensitivity of <50% in diagnosing bile duct stones. A bile duct stone seen during TUS is highly specific for stones found at ERCP and surgery. TUS is sensitive in detection of bile duct dilation (>6 mm in diameter), which is associated with the presence of bile duct stones. Mild biliary ductal dilation is seen in elderly patients and in those with prior cholecystectomy. A TUS finding of a normal-sized bile duct has a 95% negative predictive value of finding bile duct stones at ERCP.5,6 TUS findings of gallstones may also have implications for patient management. Patients with pancreatitis or jaundice often have smaller gallbladder stones on TUS (3 to 4 mm) when compared to those with cholecystitis or uncomplicated bile duct stones. Multiple small gallbladder stones are more likely to migrate in the bile duct and become clinically important.7

No single parameter accurately predicts the occurrence of bile duct stones in patients with gallstones. Most predictive models are based on a combination of clinical, biochemical, and TUS findings. For example, a patient older than 55 years who has a serum bilirubin >30 µmol/L (1.8 mg/dL) and a dilated bile duct on TUS has a 72% probability of finding bile duct stones at ERCP.8 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Standards of Practice Committee proposes a scheme to stratify patients with gallbladder stones into those at low (<10%), intermediate (10% to 50%), or high (>50%) risk of harboring bile duct stones. Other very strong predictors include clinical cholangitis and bilirubin >4 mg/dL. Strong clinical predictors are a dilated bile duct on TUS (>6 mm with an intact gallbladder) and a serum bilirubin of 1.8 to 4 mg/dL. The presence of one very strong predictor or both strong predictors categorizes a patient as being at high risk of having a bile duct stone. Age greater than 55 years, clinical gallstone pancreatitis, and abnormal liver function tests other than a raised serum bilirubin are associated with an intermediate risk of choledocholithiasis. The absence of any of these predictors is considered low risk.9

MRC, EUS, and Other Imaging Modalities in the Diagnosis of Choledocholithiasis

Two systematic reviews found both a high sensitivity (85% to 92%) and a high specificity (93% to 97%) in the detection of bile duct stones with MRC.10,11 The sensitivity of MRC appears to be related to stone size. In one study the sensitivity was 100% in stones around 1 cm in diameter and decreased to 71% for stones <5 mm in diameter. False positives can also occur12 and are mostly related to air bubbles or bilioenteric anastomosis such as a choledochoduodenostomy. MRC has the distinct advantage of being entirely noninvasive.

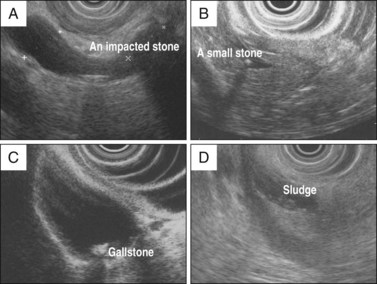

Because of the proximity of the extrahepatic bile duct to the duodenum, an echoendoscope can obtain excellent images of the bile duct (Fig. 43.1; see Chapter 31). With the patient in the lateral decubitus position and the transducer in the second portion of the duodenum and ampullary region, the distal bile duct and its intraduodenal portion can be well visualized. The common bile duct and common hepatic duct can be examined in longitudinal sections with the transducer wedged in the region of the duodenal bulb. Both radial and linear EUS have a high sensitivity (93%) and specificity (>95%) for the diagnosis of bile duct stones. Importantly, sensitivity does not seem to be affected by stone size or bile duct diameter.13

In a systematic review of five prospective blind studies with 301 patients comparing MRC and EUS, both modalities were found to have a high diagnostic performance for bile duct stones. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were marginally higher, though statistically insignificant, for EUS (0.93 versus 0.85 and 0.96 versus 0.93, respectively). For small stones and biliary sludge, EUS is likely to be more sensitive. The choice between MRC and EUS is often determined by resource availability and patient preference.11

Both MRC and EUS reliably replace diagnostic ERCP. ERCP is associated with procedural-related morbidity, mostly in the form of pancreatitis. Thus ERCP should be reserved for therapeutic purposes. In patients at intermediate or low suspicion of bile duct stones, it is logical to perform EUS before undertaking ERCP. Using EUS as the first approach reduces unnecessary ERCP and associated risks. Several randomized trials comparing EUS and ERCP as the initial approach in patients at intermediate to high risk of harboring bile duct stones14–18 showed that 27% to 40% of patients who underwent EUS were found to have bile duct stones. The negative predictive value of EUS in detecting stones was high. On follow-up only 0% to 4% of patients without EUS evidence of stones had recurrent symptoms. In a pooled analysis of 4 trials that compared ERCP and EUS first approach in 213 patients, ERCP was avoided in 143 patients (67.1%). The use of EUS reduced the risk of overall adverse events (relative risk [RR] 0.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.2 to 0.62) and specifically post-ERCP pancreatitis (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.83).19 With reduced adverse events, diagnostic EUS followed by selective ERCP is likely to be more cost-effective for patients with an intermediate probability of choledocholithiasis. The cost saving may in fact be higher if EUS and ERCP are performed during one session.

Technique of ERCP in Extraction of Bile Duct Stones

Patient Preparation (see also Chapter 9)

Patients undergoing ERCP and ES for stone extraction should have a complete blood count, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) checked before the procedure. The ASGE guidelines on periprocedural management of anticoagulation20 suggest that ES is probably safe in patients on aspirin or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) agents. Patients on clopidogrel should have the drug stopped 7 to 10 days prior to an elective procedure. Warfarin should be stopped several days prior to ES, and a heparin bridge should be used in selected patients at high risk for thromboembolic adverse events. In patients with sepsis mandating urgent ERCP, the use of anticoagulation should not defer the procedure. A short length biliary stent can be inserted for drainage as an alternative to ES.

The ASGE guidelines recommend the use of antibiotics in patients with biliary obstruction and clinical ascending cholangitis and in whom incomplete biliary drainage is anticipated (multiple stones and those with complex strictures) and the continuation of antibiotics after the procedure. It has not been shown conclusively that the use of preprocedural antibiotics decreases post-ERCP cholangitis in those with biliary obstruction in the absence of cholangitis and in whom complete biliary drainage is likely after ERCP.21 We recommend the routine use of antibiotics in immunocompromised patients.

We prefer to perform ERCP with the use of anesthesia-administered propofol. Patients with sepsis who have unstable hemodynamics or potential airway problems should be endotracheally intubated for the procedure (see Chapter 5). Prior to ERCP a short period of resuscitation is often desirable in patients with sepsis and hypotension. The patient is usually placed prone. Increasingly we perform ERCP with patients in the left lateral decubitus position. A duodenoscope with a 4.2-mm instrument is used in anticipation of large stones, the use of mechanical lithotripsy, and insertion of a 10 Fr stent.

Biliary Cannulation, Cholangiography and Sphincterotomy

We recommend wire-guided biliary cannulation since injection of contrast can increase hydrostatic pressure and cause mechanical trauma to the pancreatic duct (see Chapter 18). In a pooled analysis of controlled trials that compared contrast and wire-guided techniques of biliary cannulation,22 a significantly lower rate of pancreatitis was seen with wire-guided cannulation.

We use a pull-type sphincterotome, typically with a 25-mm cutting wire preloaded with a 0.025- or 0.035-in guidewire that has a hydrophilic terminal portion. Flexing of the sphincterotome provides additional angle for cannulation. Upon deep cannulation of the bile duct, the sphincterotome is advanced above the cystic duct junction. Injection of contrast with the catheter positioned at the distal bile duct can cause a small stone to pass into intrahepatic ducts, making subsequent extraction difficult. Bile is first aspirated and exchanged with contrast. We avoid overdistension of the bile duct, as an increase in biliary pressure can induce bacteremia in patients with cholangitis. In patients with cholangitis, especially suppurative cholangitis, the primary aim is to provide biliary drainage. This can be accomplished by insertion of a 7 Fr nasobiliary drain or a short stent to prevent calculous impaction. There are several randomized controlled trials comparing placement of a nasobiliary drain and a stent; no difference in biliary drainage and adverse events was seen. We prefer the use of a short stent, as a nasobiliary drain can kink at the back of the oropharynx; is prone to accidental dislodgement, particularly in delirious or elderly patients; and can be a source of discomfort.23–25

The technique of optimizing cholangiography during ERCP has been reviewed (see Chapter 3).26 A scout film should be obtained prior to insertion of the endoscope. Devices for cannulation should be prefilled with contrast to avoid injecting air into the bile duct. We use half-strength contrast for better visualization of stones. When compared to air bubbles, stones are often faceted. To visualize segments of the bile duct behind the duodenoscope, one can gently push the endoscope into a semilong position. With the patient in a prone position, the left lobar ducts are more dependent. Small stones in the left lobar ducts may therefore migrate into the bile duct as the patient is rolled to a lateral or supine position. Despite position change the sensitivity of cholangiography is imperfect and varies between 89% and 93% in diagnosing bile duct stones. Small stones can still be missed in a spacious and dilated bile duct.

When a cholangiogram is obtained and no apparent stones are identified, the decision to perform an empirical ES is influenced by the likelihood of finding a stone based on clinical parameters prior to ERCP. In cases where there is strong clinical suspicion of a stone (stone seen on TUS or a patient with clinical cholangitis), we advocate a more liberal policy in performing empiric ES. An ES enables a more thorough ductal evaluation. With this approach, more small stones and sludge are detected more often. In a randomized study of ES or no endoscopic treatment, patients with cholangitis and cholelithiasis but without bile duct stones seen on ERCP who underwent ES had a reduction in recurrent stones and sepsis at a mean follow-up period of 22 months.27 In most circumstances the risk of missing a bile duct stone outweighs that of an unnecessary ES. When expertise is available, EUS and intraductal ultrasonography are ancillary techniques that may aid in resolving the dilemma.

ES is performed with the distal portion of the cutting wire in the duct and with minimal wire tension (see Chapter 16). The incision proceeds in a stepwise manner. If an uncontrolled electrosurgical generator is used, excessive tension on the cutting wire and tissue contact during ES can result in a “zipper cut” with coagulated tissue being forced open, resulting in perforation and bleeding. We prefer the use of a blended current in a pulsed mode or an “ENDOCUT” mode. It was initially suggested that a continuous pure cutting current minimizes coagulation injury around the papillary orifice and reduces the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, subsequent studies have shown that the use of pure cutting current increases intraprocedural bleeding without reducing pancreatitis.28

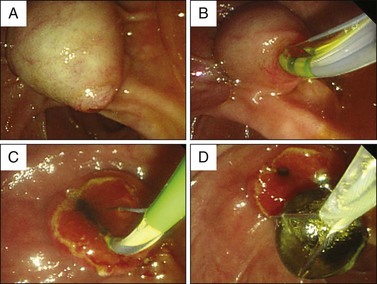

It is often difficult to define the upper limits of a biliary sphincterotomy. The size of the ES varies with the size and configuration of the distal bile duct. In patients with a narrow, tapering distal bile duct, only a limited ES can be made. In the presence of a dilated bile duct with a flat and square distal end, a more generous ES is possible. Often a transverse fold is seen above the papilla. One can often cut to the top of the fold and the intraduodenal portion of the ampulla and the duodenal wall. As muscle fibers to the biliary sphincter are severed, one can see free bile flow. Another sign of an adequate sphincterotomy is free passage of a fully bowed sphincterotome with a 25-mm cutting wire through the sphincterotomy orifice (Fig. 43.2).

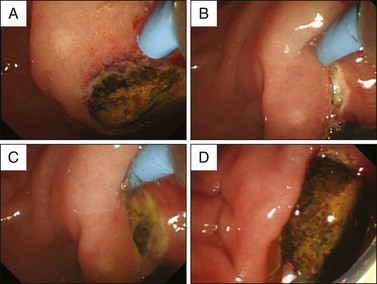

The use of needle-knife precut sphincterotomy has consistently been identified as a risk factor for adverse events. It is often debated whether the high rate of adverse events is consequent to protracted attempts at cannulation or to needle-knife sphincterotomy itself. Many experts advocate early precutting after initial attempts at cannulation fail. In patients with bile duct stones, the intrabiliary pressure is usually high from obstructing stones. Cannulation of the biliary sphincter is often easy. In the situation of an impacted stone at the ampulla, incision onto the bulging ampulla with a needle knife is safe, as the stone protects the pancreatic orifice (Fig. 43.3). Needle-knife sphincterotomy often disimpacts the stone and relief of obstruction is often dramatic. A full discussion of the use of needle-knife sphincterotomy is provided in Chapter 14. There should be a clear indication for access to the bile duct. The endoscopist must be aware of inherent risks in the particular patient. After multiple pancreatic duct injections or wire passages, placement of a short 5 Fr pancreatic duct can reduce post-ERC pancreatitis.29 After pancreatic stent placement the appropriate bile duct axis for precut can be determined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree