The cornerstone of treatment for localized renal tumors is surgical excision, which until recently was accomplished primarily through radical nephrectomy. The last 2 decades have seen a rapid evolution in the surgical management of renal cell carcinoma, marked by the increased use of nephron-sparing surgery and the application of minimally invasive techniques. A plethora of surgical options now are available. This article discusses the optimal surgical approach to renal tumors in various clinical scenarios. In all these discussions we assume that a proactive approach to treatment is indicated and desired, recognizing that active surveillance is always an additional option to consider in certain subpopulations such as the elderly or infirm.

Evolution of the surgical management of localized renal cell carcinoma

Intensive study of the biology of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has advanced the understanding of its pathogenesis and led to novel adjuvant therapies, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Even in this era of molecular targeted therapy, however, surgical excision remains the primary curative treatment for RCC. Historically, radical nephrectomy (RN), with or without ipsilateral adrenalectomy and regional lymphadenectomy, has been the reference standard for curative treatment of localized RCC. With prevailing data showing excellent oncologic efficacy, RN long has been the treatment of choice in patients who have localized unilateral RCC and a normally functioning contralateral kidney.

With the advent of laparoscopy, minimally invasive techniques have been applied to RN resulting in an appealing alternative to open surgery that is associated with decreased morbidity and quicker convalescence. Generally used in the management of localized RCC without invasive features or substantial venous or nodal involvement, these techniques have had survival outcomes comparable with those of the open approach, and laparoscopic RN now is firmly established as one of the standards in this field.

Despite its long history and proven efficacy in treating kidney cancer, changes in the epidemiology of RCC and recent data clarifying a link between RN and chronic kidney disease have called into question the status of RN as the treatment of choice in patients who have a normal contralateral kidney. During the last decade, there has been stage and size migration in RCC because of the increased incidental detection of small (< 4 cm) renal masses, which now account for the majority of cases that present for surgical management. Moreover, there now is evidence demonstrating that renal preservation is critical even in patients who have normal contralateral renal function because there is a higher risk of subsequent chronic kidney disease following RN for RCC.

As a result, surgical options for localized RCC have expanded in the past 2 decades to include nephron-sparing surgery (NSS), which encompasses open and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (OPN and LPN, respectively) as well as newer modalities based on thermal ablation. Partial nephrectomy (PN) has demonstrated curative potential equal to RN in the treatment of localized RCC according to comparison studies. For example, Lau and colleagues performed a matched comparison of 164 patients treated with either RN or PN and reported no significant differences between the two treatment groups in overall and cancer-specific survival, complication rate, and development of metastatic disease. Patients who underwent PN, however, demonstrated a decreased incidence of chronic kidney disease (defined by a serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL) as well as a decreased rate of proteinuria at a follow-up of 10 years. Other groups have demonstrated similar findings, and the increased incidence of renal insufficiency following RN persists even after controlling for potential confounding factors such as diabetes or hypertension.

The primary concern from these studies is that RN can have deleterious effects on a patient’s long-term renal function and overall health, because population-based studies have shown a correlation between chronic kidney disease and increased risks of morbid cardiac events, hospitalization for any reason, and death. Another concern with indiscriminate application of RN is the possibility of late recurrence of RCC in the contralateral kidney; options for salvage treatment become more limited in the context of a solitary kidney. Overall, the current evidence supports a judicious use of RN in the treatment of localized renal masses that otherwise may be amenable to NSS, and this principle now is an overriding consideration in the management of patients who have small renal masses. Undoubtedly, RN remains a viable option when the primary tumor is prohibitively large (ie, > 7 cm), replaces too much renal parenchyma, is in a location not amenable to NSS, or in some older patients who desire surgical excision but for whom the risks associated with a complex PN may not be acceptable.

The ascendancy of elective partial nephrectomy

PN involves the complete resection of a localized renal mass with adequate surgical margins while preserving as much normal renal parenchyma as possible. Historically, PN has been used in patients who have imperative indications for renal preservation to avoid the need for renal replacement therapy. Such patients include individuals who have a solitary kidney (functional or anatomic), those who have bilateral tumors, or those affected by local or systemic conditions that may place them at high risk for subsequent renal failure (eg, diabetes, hypertension, or renovascular disease).

The indications for NSS have expanded during the past 2 decades, and elective PN now is established as a standard of care for small (< 4 cm) renal tumors in patients who have a normal opposite kidney ( Table 1 ). Elective PN is concordant with the current mandate to optimize renal function on a long-term basis but also offers a variety of other important advantages. It avoids overtreatment of benign renal histologies that represent approximately 20% of all small, enhancing renal tumors, its cost effectiveness is equivalent to that of RN, and some studies also demonstrate better quality of life after PN than after RN. With careful patient selection and adequate expertise, PN also can provide a perioperative morbidity profile similar to that of RN.

| Series | No. of Patients | Disease-Specific Survival (%) | Local Recurrence (%) | Mean Tumor Size (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazeed et al (1986) | 23 | 100 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Carini et al (1988) | 10 | 90 | 0 | 3.5 |

| Morgan and Zincke (1990) | 20 | 100 | 0 | 3.1 |

| Selli et al (1991) | 20 | 90 | 0 | < 3.5 |

| Provet et al (1991) | 19 | 100 | 0 | 2.6 |

| Steinbach et al (1992) | 72 | 94.4 | 2.7 (2 cases) | N/A |

| Moll et al (1993) | 98 | 100 | 1 (1 cases) | 4 |

| Thrasher et al (1994) | 6 | — | 0 | 4.3 |

| Lerner et al (1996) | 54 | 92 | 5.6 (3 cases) | < 4 |

| D’Armiento et al (1997) | 19 | 96 | 0 | 3.34 |

| van Poppel et al (1998) | 51 | 98 | 0 | 3 |

| Herr (1999) | 70 | 97.5 | 1.5 (2 cases) | 3 |

| Hefez et al (1999) | 45 | 100 | 0 | < 4 |

| Barbalias et al (1999) | 41 | 97.5 | 7.3 (3 cases) | 3.5 |

| Belldegrun et al (1999) | 63 | 100 | 3.2 (2 cases) | < 4 |

| Filipas et al (2000) | 180 | 98 | 1.6 (3 cases) | 3.3 |

| Delakas et al (2002) | 118 | 97.3 | 3.9 (cases) | 3.4 |

| Total | 909 | 90–100 | 0–7.3 | 2–4.3 cm |

Although preservation of renal function and prevention of chronic kidney disease are important considerations, local cancer control is still the primary goal of any cancer surgery, and equivalent oncologic efficacy must be demonstrated before PN can be accepted as a viable alternative to RN in an elective setting. In fact, the technical success rate of PN for RCC is excellent, and the prevailing data indicate extended cancer-specific survival rates on par with those observed after RN. The largest reported study of PN for localized RCC is from the Cleveland Clinic and reviewed the results of 485 patients who had sporadic RCC, demonstrating overall and cancer-specific 5-year survival rates of 81% and 92%, respectively. Long-term results of PN for localized RCC have confirmed its enduring oncologic efficacy. Fergany and colleagues demonstrated a 10-year cancer-specific survival rate of 73% as well as preservation of renal function in 93% of patients treated for localized sporadic RCC. Likewise, Herr reported overall and metastasis-free survival rates of 93% and 97%, respectively, at a median follow-up of 10 years in a cohort of patients who had unilateral renal tumors and a normal opposite kidney. Furthermore, studies from institutions with extensive experience with PN have found no significant differences in survival between patients who had low-stage, localized RCC treated with either PN or RN. Butler and colleagues noted 5-year cancer-specific survival rates of 97% and 100% for patients treated with RN and PN, respectively, and investigators from the Mayo Clinic noted similar rates of 96% and 92%.

Careful patient selection, which probably contributed to the favorable outcomes demonstrated in these reports, can help determine which patients will benefit from elective PN versus RN. This precaution will ensure that PN is used safely and appropriately, thereby optimizing outcomes and reducing the incidence of tumor recurrence. Preoperative patient characteristics that may predict postoperative renal insufficiency after RN include elevated preoperative serum creatinine level, proteinuria, and hypertension, and a nomogram to predict postnephrectomy renal insufficiency incorporating some of these variables has been developed by investigators at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. In addition, a number of clinical criteria related to low tumor burden seem to be associated with improved patient outcomes following PN, including small tumor size (eg, < 4 cm), low tumor stage, and a solitary lesion. In another study from the Cleveland Clinic, PN performed in patients fitting these criteria resulted in a 5-year cancer-specific survival of 100% with no cases of postoperative tumor recurrence.

A significant concern with the use of PN in RCC is indeed the risk of local recurrence in the ipsilateral kidney. Fortunately, overall rates of local recurrence following NSS in the literature range from 0% to 10%, and when considering tumors smaller than 4 cm (ie, the types of tumors commonly treated with elective PN), the incidence is approximately 1% to 3%. Taken together, these data justify the growing confidence in PN as an oncologically equivalent alternative to RN in patients who have a solitary, unilateral tumor smaller than 4 cm and normal contralateral renal function.

The ascendancy of elective partial nephrectomy

PN involves the complete resection of a localized renal mass with adequate surgical margins while preserving as much normal renal parenchyma as possible. Historically, PN has been used in patients who have imperative indications for renal preservation to avoid the need for renal replacement therapy. Such patients include individuals who have a solitary kidney (functional or anatomic), those who have bilateral tumors, or those affected by local or systemic conditions that may place them at high risk for subsequent renal failure (eg, diabetes, hypertension, or renovascular disease).

The indications for NSS have expanded during the past 2 decades, and elective PN now is established as a standard of care for small (< 4 cm) renal tumors in patients who have a normal opposite kidney ( Table 1 ). Elective PN is concordant with the current mandate to optimize renal function on a long-term basis but also offers a variety of other important advantages. It avoids overtreatment of benign renal histologies that represent approximately 20% of all small, enhancing renal tumors, its cost effectiveness is equivalent to that of RN, and some studies also demonstrate better quality of life after PN than after RN. With careful patient selection and adequate expertise, PN also can provide a perioperative morbidity profile similar to that of RN.

| Series | No. of Patients | Disease-Specific Survival (%) | Local Recurrence (%) | Mean Tumor Size (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazeed et al (1986) | 23 | 100 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Carini et al (1988) | 10 | 90 | 0 | 3.5 |

| Morgan and Zincke (1990) | 20 | 100 | 0 | 3.1 |

| Selli et al (1991) | 20 | 90 | 0 | < 3.5 |

| Provet et al (1991) | 19 | 100 | 0 | 2.6 |

| Steinbach et al (1992) | 72 | 94.4 | 2.7 (2 cases) | N/A |

| Moll et al (1993) | 98 | 100 | 1 (1 cases) | 4 |

| Thrasher et al (1994) | 6 | — | 0 | 4.3 |

| Lerner et al (1996) | 54 | 92 | 5.6 (3 cases) | < 4 |

| D’Armiento et al (1997) | 19 | 96 | 0 | 3.34 |

| van Poppel et al (1998) | 51 | 98 | 0 | 3 |

| Herr (1999) | 70 | 97.5 | 1.5 (2 cases) | 3 |

| Hefez et al (1999) | 45 | 100 | 0 | < 4 |

| Barbalias et al (1999) | 41 | 97.5 | 7.3 (3 cases) | 3.5 |

| Belldegrun et al (1999) | 63 | 100 | 3.2 (2 cases) | < 4 |

| Filipas et al (2000) | 180 | 98 | 1.6 (3 cases) | 3.3 |

| Delakas et al (2002) | 118 | 97.3 | 3.9 (cases) | 3.4 |

| Total | 909 | 90–100 | 0–7.3 | 2–4.3 cm |

Although preservation of renal function and prevention of chronic kidney disease are important considerations, local cancer control is still the primary goal of any cancer surgery, and equivalent oncologic efficacy must be demonstrated before PN can be accepted as a viable alternative to RN in an elective setting. In fact, the technical success rate of PN for RCC is excellent, and the prevailing data indicate extended cancer-specific survival rates on par with those observed after RN. The largest reported study of PN for localized RCC is from the Cleveland Clinic and reviewed the results of 485 patients who had sporadic RCC, demonstrating overall and cancer-specific 5-year survival rates of 81% and 92%, respectively. Long-term results of PN for localized RCC have confirmed its enduring oncologic efficacy. Fergany and colleagues demonstrated a 10-year cancer-specific survival rate of 73% as well as preservation of renal function in 93% of patients treated for localized sporadic RCC. Likewise, Herr reported overall and metastasis-free survival rates of 93% and 97%, respectively, at a median follow-up of 10 years in a cohort of patients who had unilateral renal tumors and a normal opposite kidney. Furthermore, studies from institutions with extensive experience with PN have found no significant differences in survival between patients who had low-stage, localized RCC treated with either PN or RN. Butler and colleagues noted 5-year cancer-specific survival rates of 97% and 100% for patients treated with RN and PN, respectively, and investigators from the Mayo Clinic noted similar rates of 96% and 92%.

Careful patient selection, which probably contributed to the favorable outcomes demonstrated in these reports, can help determine which patients will benefit from elective PN versus RN. This precaution will ensure that PN is used safely and appropriately, thereby optimizing outcomes and reducing the incidence of tumor recurrence. Preoperative patient characteristics that may predict postoperative renal insufficiency after RN include elevated preoperative serum creatinine level, proteinuria, and hypertension, and a nomogram to predict postnephrectomy renal insufficiency incorporating some of these variables has been developed by investigators at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. In addition, a number of clinical criteria related to low tumor burden seem to be associated with improved patient outcomes following PN, including small tumor size (eg, < 4 cm), low tumor stage, and a solitary lesion. In another study from the Cleveland Clinic, PN performed in patients fitting these criteria resulted in a 5-year cancer-specific survival of 100% with no cases of postoperative tumor recurrence.

A significant concern with the use of PN in RCC is indeed the risk of local recurrence in the ipsilateral kidney. Fortunately, overall rates of local recurrence following NSS in the literature range from 0% to 10%, and when considering tumors smaller than 4 cm (ie, the types of tumors commonly treated with elective PN), the incidence is approximately 1% to 3%. Taken together, these data justify the growing confidence in PN as an oncologically equivalent alternative to RN in patients who have a solitary, unilateral tumor smaller than 4 cm and normal contralateral renal function.

Upper limits of tumor size for elective partial nephrectomy

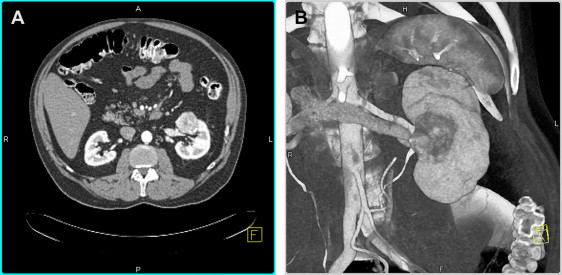

Initial studies assessing the impact of tumor size on treatment outcomes following NSS for localized RCC demonstrated a significantly lower rate of recurrence and improved survival for tumors smaller than 4 cm. Such data provided the rationale for using a 4-cm cutoff as the upper limit for elective PN and a revision of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for confined RCC in 2002. During the last decade, PN has indeed become a standard of care for the treatment of T1a tumors. With the excellent oncologic efficacy displayed by PN and the importance of renal preservation, some institutions now are expanding the indications for elective PN to include T1b tumors (4–7 cm) ( Fig. 1 ).

Several studies have suggested that elective PN in carefully selected patients can achieve oncologic efficacy equivalent to RN in the treatment of stage T1b renal masses. For example, a large multi-institutional study demonstrated no significant difference in the rates of distant or local recurrence or cancer-specific mortality between patients undergoing PN and those undergoing RN for T1b tumors. Similarly, Leibovich and colleagues found comparable cancer-specific and distant metastases-free survival rates for patients treated with either PN or RN for pT1b tumors after controlling for pathologic features such as stage, grade, and histologic subtype. Although such data are encouraging, patient selection almost certainly contributed to the favorable outcomes in these series; patients who underwent PN tended to be younger, and their tumors tended to be smaller as well as of lower stage and grade. Peripheral tumor location also was more common in these series. Elective PN for T1b tumors in a broader patient population remains controversial.

Open versus laparoscopic partial nephrectomy

Significant advances in the field have allowed current laparoscopic techniques to duplicate the essential surgical principles of OPN, including clamping of the renal vasculature to provide a bloodless field when necessary, careful resection of the mass with a rim of normal parenchyma, and intracorporeal suturing to close the collecting system and repair the capsular defect. Nevertheless, LPN can be technically demanding, and certain obstacles remain, including longer warm ischemia times and hemostatic concerns. As such, the decision to perform LPN versus OPN currently may depend more on the experience and comfort level of the surgeon than on oncologic guidelines. Not surprisingly, the practice of LPN has been limited largely to specialized tertiary care centers.

A recent multicenter study comparing OPN and LPN for single renal masses addressed the questions of oncologic efficacy, impact on renal function, and postoperative morbidity and provides useful information about the relative merits of these approaches. This study comprised 1800 patients including 771 undergoing LPN and 1029 undergoing OPN for a single renal tumor smaller than 7 cm. Similar cancer-specific survival (99.3% versus 99.2% at 3 years) and postoperative renal function (97.9% versus 99.6% functioning renal units at 3 months) was demonstrated. Compared with OPN, LPN was associated with decreased operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay but demonstrated longer warm ischemia times and more postoperative complications requiring additional interventions ( Table 2 ). In particular, urologic complications (primarily urine leak and hemorrhage) were more common after LPN (9.2% versus 5.0%, P = .0006), and postoperative hemorrhage was almost threefold more common after LPN (4.2% versus 1.6%, P = .0002). It should be noted that patients treated with OPN were a higher-risk group than the LPN cohort: a greater percentage of patients in the OPN group demonstrated decreased performance status, impaired renal function, and symptomatic presentation. Furthermore, tumors in the OPN cohort more often were malignant, were larger on average, and more were centrally located or involved a solitary kidney (see Table 2 ). These observations suggest that in this study patient selection and tumor biology were substantially different in the two groups, with all comparisons reflecting a higher-risk population for OPN.