Chapter 13 Cannulation of the Major Papilla

Despite advances in imaging and device technology over the past decade, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) continues to be technically challenging and subject to adverse events and procedure failure. To some extent this is accounted for by the knowledge that among the most difficult aspects of the procedure is the very first step: selective biliary cannulation (SBC). Outside of expert high volume centers, failed biliary cannulation occurs in up to 20% of cases.1 Repeated and prolonged attempts at cannulation increase the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), delay definitive therapy, and necessitate alternative therapeutic techniques with inferior safety profiles.2–5

In any patient with a given preprocedural risk profile (based on age, sex, and indication, e.g., choledocholithiasis as compared with sphincter dysfunction), cannulation technique and outcome is the primary determinant of adverse events in most ERCP procedures and is obviously important in achieving success.5 Preceding this and not to be overlooked, the first step in optimizing outcomes and minimizing ERCP adverse events is appropriate patient selection. This is done by avoiding diagnostic ERCP and using other less hazardous imaging modalities such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) when the pretest probability of the need for intervention at ERCP is low. Careful patient selection eliminates the awkward situation that may occur when conventional cannulation techniques fail and the probability of pathology is low. Then a decision must be made as to whether to proceed with a more aggressive and potentially more hazardous ancillary technique (e.g., precut) to achieve SBC. Suddenly the risks of continuing the procedure may dramatically outweigh the clinical benefit of technical success. Therefore all possible cannulation scenarios must be envisaged before ERCP is undertaken, and the endoscopist must be comfortable with an array of techniques. Once under way, the risk profile of the patient and the intent of the procedure must always be factored into the approach. In an elderly patient with jaundice due to obstructive biliary disease and no other anatomic or patient-related risk factors, time can be spent on different conventional access techniques to achieve SBC. Conversely, in younger patients with difficult cannulation, or possible sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), early and repeated access to the pancreatic duct will dictate a change in cannulation strategy and early placement of a pancreatic stent. However, sometimes the best decision during ERCP is to stop the procedure.6

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Establishing the Duodenal Position

(a) The endoscope is gently advanced for 2 to 3 cm with slight counterclockwise torque, the left-right (LR) wheel is then turned right and locked, and then with clockwise torque of the shaft and gentle upward deflection of the big wheel the instrument is withdrawn and the endoscopist has the sense of pulling oneself beneath the papilla. This is my preferred technique, and it minimizes endoscopic insertion length and patient discomfort.

(b) Alternatively, one may pass the tip beyond the papilla to the distal second part and again perform full right lock of the LR wheel and essentially repeat the endoscope withdrawal steps outlined in (a).

On occasions with a mobile second part of the duodenum (e.g., after hepatic lobectomy) or abnormally inferior papilla, technique (b) may be the only means to achieve a satisfactory position. Initially the papilla should be positioned in the center of the monitor for inspection, but since the catheter will emerge from the lower half of the right edge of the screen image, for optimal cannulation the papilla’s monitor position should generally be slightly more superior and to the right (Fig. 13.1). For successful SBC, the duodenoscope position should be stable and the endoscopist must feel as though the scope tip is below or at least adjacent to the papilla (i.e., the papilla is easily positioned above the horizontal midpoint of the monitor). If the endoscope is above the papilla, cannulation will be difficult. Cannulation attempts should not commence until all efforts to achieve a satisfactory position have been exhausted. Occasionally a long scope position will be necessary. This is achieved by pushing the instrument inferiorly with counterclockwise torque on the shaft toward the left-hand wall (as seen on the monitor). The insertion tube of the scope will bow along the greater curve of the stomach, with the tip of the endoscope dipping below the papilla, and then in approximately 80% of cases come back up adjacent to the papilla but in a more favorable infrapapillary orientation.

Devices and Equipment (see also Chapter 4)

Soft-tipped hydrophilic guidewires: usually 0.035 in, occasionally 0.025 or 0.021 in; JAG or Dream wire (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.), Tracer Metro wire (Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, N.C.), or Visiglide wire (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo). When encountering difficult cannulation of the pancreatic duct or for use through a 5-4-3 Fr cannula, a 0.018-in platinum-tipped wire (Roadrunner, Cook Endoscopy) is useful. The 0.035-in loop-tipped guidewire (Cook Endoscopy) is an emerging alternative wire. Many other varieties of specialty wires exist and may have particular advantages in niche situations.

Soft-tipped hydrophilic guidewires: usually 0.035 in, occasionally 0.025 or 0.021 in; JAG or Dream wire (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.), Tracer Metro wire (Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, N.C.), or Visiglide wire (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo). When encountering difficult cannulation of the pancreatic duct or for use through a 5-4-3 Fr cannula, a 0.018-in platinum-tipped wire (Roadrunner, Cook Endoscopy) is useful. The 0.035-in loop-tipped guidewire (Cook Endoscopy) is an emerging alternative wire. Many other varieties of specialty wires exist and may have particular advantages in niche situations.

Triple-lumen sphincterotomes with 20-, 25-, or 30-mm cutting wire: Olympus sphincterotome (Olympus Corporation); DomeTip Fusion, Omni 35 and Omni 21, or Tritome (Cook Endoscopy); or Autotome or Dreamtome RX 44 or 39 (Boston Scientific).

Triple-lumen sphincterotomes with 20-, 25-, or 30-mm cutting wire: Olympus sphincterotome (Olympus Corporation); DomeTip Fusion, Omni 35 and Omni 21, or Tritome (Cook Endoscopy); or Autotome or Dreamtome RX 44 or 39 (Boston Scientific).

3 or 5 Fr pancreatic stents: Zimmon or Geenen Sof-Flex stent (Cook Endoscopy).

3 or 5 Fr pancreatic stents: Zimmon or Geenen Sof-Flex stent (Cook Endoscopy).

Microprocessor-controlled electrosurgical generator delivering alternating cycles of short pulse cutting with more prolonged coagulation current: ERBE VIO 300 (ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany) or Olympus ESG-100 (Olympus Corporation).

Microprocessor-controlled electrosurgical generator delivering alternating cycles of short pulse cutting with more prolonged coagulation current: ERBE VIO 300 (ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany) or Olympus ESG-100 (Olympus Corporation).

Commercially available needle knives (Olympus Corporation, Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific).

Commercially available needle knives (Olympus Corporation, Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific).

Cannulation Technique

Most expert endoscopists opt to cannulate the naive papilla with a sphincterotome (ST), given that almost all procedures are now therapeutic and, compared to a catheter, the ST orientation to the distal biliary tree is favorable and adjustable. High-quality comparative data are limited but indicate superior outcomes with an ST when compared with a standard catheter.7,8 The imprecise technique of impacting the ST into the papilla and injecting contrast should be avoided. This results in papillary trauma and often leads to pancreatic duct opacification. In general, the preferred technique is to selectively insert the ST beyond the papilla and into the bile duct atraumatically. To comprehend the mechanics of biliary cannulation, a useful analogy is to imagine passing your hand up a shirt sleeve that is hanging over the back of a chair. The sleeve may be of variable length and caliber, draped over the chair at varying angles, and either floppy or more rigid. It is not possible to fix the sleeve in place, so gentle manipulation is required and forceful distortion is unlikely to be successful.

Wire or Contrast?

Although long-established techniques were based on initial contrast opacification of the biliary tree, this may result in inadvertent filling of the pancreatic duct (PD) and progressive stepwise opacification to the body or tail from repeated injections to check the position of the cannulating device. The risk of PEP increases with the number of PD injections and the extent of PD opacification.3,5,9 While contrast cannulation (CC) has the theoretical advantage of demonstrating the anatomy with the potential to direct the cannulation strategy based on static images, it often opacifies the PD repeatedly. The inherent limitation of the technique is that in most situations one cannot confirm successful access to the desired duct without contrast injection. Wire-guided cannulation (WGC) has been proposed as a means of enhancing technical success while reducing the risk of PEP. A soft hydrophilic guidewire has the theoretical advantages of facilitating deep instrumentation of the bile duct, confirming duct selection without contrast injection, and in many cases completely eliminating contrast opacification of the pancreatic duct. Even if gently passed into the PD it may not significantly increase the risk of PEP. Accumulating evidence from randomized trials suggests that the wire-guided technique is the preferred approach.10–12

At least two meta-analyses have examined all five fully published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising 1762 individuals.13,14 All studies satisfy at least 4 of 5 standard trial quality measures, such as adequate power or analysis by intention to treat methodology. Pooled analysis of bile duct cannulation success yielded an odds ratio (OR) of 2.05 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.27–3.31) in favor of WGC over CC, with overall primary cannulation rates of 85.3% and 74.9%, respectively. Precut or needle-knife sphincterotomy (NKS) was performed in 91 of 882 (10.3%) and 129 of 880 (14.7%) of the WGC and CC groups, respectively.13 Excluding the two studies with crossover design (which do not allow PEP to be ascribed to a single technique), analysis of the three remaining studies yielded an OR for PEP of 0.23 (95% CI 0.13–0.41) in favor of WGC.13 No study significantly influenced the pooled estimate and heterogeneity between the studies was not detected. The other meta-analysis, which included two smaller studies (published only as abstracts), derived the same conclusions.14 WGC when compared with CC was associated with reduced PEP (3.2% versus 8.7%, relative risk [RR] 0.38, 95% CI 0.19–0.76) and enhanced primary cannulation (89% versus 78%, RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05–1.35). In addition, subgroup analysis showed a significantly lower occurrence of PEP after guidewire entry versus contrast injection of the pancreatic duct (1.1% versus 9.5%, RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.06–0.58).14 A Cochrane review is currently under way.

While the evidence is strong, caution is required. Two of the five studies, accounting for 40% of the patients, were single operator trials. Care should be exercised before generalizing studies involving a single operator to wider practice. Furthermore, a consensus definition of WGC has not yet been promulgated. The techniques used differed somewhat among the various studies. The unifying principle is that the guidewire is used to confirm deep biliary access and thus opacification of the pancreatic duct is generally avoided or minimized.15 At least three variations of this technique exist and their use does and should vary depending on the morphology of the papilla.15

(a) Direct access with the sphincterotome: The ST is used to enter (drop or pop into) the biliary duct (BD) and then the wire is advanced, its direction confirming SBC. This technique is used frequently by experienced biliary endoscopists and will swiftly succeed in more than 50% of cases. It is primarily used when the papilla is of normal size and position and a cannulation challenge is not anticipated. It may also work with a floppy papilla.

(b) Sphincterotome then wire: The ST is advanced 2 to 3 mm beyond the luminal aspect of the papilla in the biliary orientation and then the wire is gently advanced (either by the assistant [long wire] or by the endoscopist or the assistant [short wire]) to achieve SBC. This is useful in a floppy or mobile papilla or when technique (a) fails; this modification can be swiftly applied without withdrawing the ST. The ST can be used to straighten the intramural segment by drawing back on the impaled papilla and applying suction to encourage the papilla down onto the bowed ST.

(c) Wire lead technique: The tip of the wire is positioned approximately 2 mm beyond the tip of the ST and the wire ST complex is then advanced in the biliary direction into the papilla. It may drop or pop into the BD as in technique (a), or the wire can be advanced as in technique (b) to achieve SBC. This technique is especially useful when the papilla is small and the tip of the ST is larger than the papilla. The wire acts as an introducer (Videos 13.1 and 13.2).

These techniques are all somewhat different, although they are unified by the goal of contrast-free SBC. Potentially they all have advantages and risks. For instance, a forcefully inserted guidewire may dissect intramurally within the papilla, creating a false passage. It is likely, although not yet proven, that a given technique may have advantages dependent on patient-related factors, particularly the morphology of the papilla. A large floppy papilla with a long intraduodenal segment of BD would be better suited to initial ST insertion beyond the orifice and then the intraduodenal segment straightened; SBC may subsequently occur with either wire or ST directly. Further trials of WGC more closely reporting on papillary morphology would be helpful.

Papilla Assessment and Basic Technique

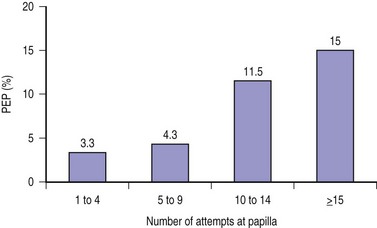

It is useful to ask the assistants to (quietly) prospectively record the number of separate attempts on the papilla and the total cannulation time from the first touch of the papilla. This information can aid in the decision as to when alternative or ancillary cannulation techniques should be considered or the procedure terminated. The number of attempts (and as a corollary, total cannulation time) is an independent predictor of the risk of PEP, with the risk rising substantially after about 9 to 10 attempts (Fig. 13.2).5,12 A cannulation attempt is defined as sustained contact between the cannulating device and the papilla for at least five seconds.

The face of the papilla: This can be compared to the face of a clock. As a reference point, the 12 o’clock position is aligned with the long axis of the papilla and is usually the most superior point on the face of the papilla. However, if duodenal anatomy is distorted (due to a diverticulum, neoplasm, or as can be seen in older patients), the papilla may be rotated anywhere along its long axis (usually to the left) and the true 12 o’clock position may not be the most superior (cephalad) part of the papilla. In these cases, use the position of the long axis as the 12 o’clock reference point. In more than 95% of cases, the biliary orifice is located between 9 and 12 o’clock and often in the 11 o’clock position.

The face of the papilla: This can be compared to the face of a clock. As a reference point, the 12 o’clock position is aligned with the long axis of the papilla and is usually the most superior point on the face of the papilla. However, if duodenal anatomy is distorted (due to a diverticulum, neoplasm, or as can be seen in older patients), the papilla may be rotated anywhere along its long axis (usually to the left) and the true 12 o’clock position may not be the most superior (cephalad) part of the papilla. In these cases, use the position of the long axis as the 12 o’clock reference point. In more than 95% of cases, the biliary orifice is located between 9 and 12 o’clock and often in the 11 o’clock position.

The intrapapillary or intramural segment of the BD: This is the portion of the BD located between the biliary orifice and the BD beyond the duodenal wall. It is variously referred to as the intramural, intraduodenal, or occasionally intrapapillary segment. I will use the term intramural segment. It is of variable length, angulation, and rigidity, largely dependent on the size of the papilla (Fig. 13.3), and may create different cannulation challenges and take a course quite different to that implied by the duodenal orientation of the face (Fig. 13.4), although often it follows the same line (Fig. 13.1). For seamless deep instrumentation, it will often be necessary to eventually align the cannulating device with this axis after the initial 11 o’clock contact position has been achieved. A long intramural segment is easily distorted by forceful attempts.

The intrapapillary or intramural segment of the BD: This is the portion of the BD located between the biliary orifice and the BD beyond the duodenal wall. It is variously referred to as the intramural, intraduodenal, or occasionally intrapapillary segment. I will use the term intramural segment. It is of variable length, angulation, and rigidity, largely dependent on the size of the papilla (Fig. 13.3), and may create different cannulation challenges and take a course quite different to that implied by the duodenal orientation of the face (Fig. 13.4), although often it follows the same line (Fig. 13.1). For seamless deep instrumentation, it will often be necessary to eventually align the cannulating device with this axis after the initial 11 o’clock contact position has been achieved. A long intramural segment is easily distorted by forceful attempts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree