Chapter 16 Biliary Sphincterotomy

Description of the Technique

Premedication, duodenoscopy, and the approach to the papilla are the same as for diagnostic ERCP, as discussed in Chapters 5 and 13. The use of a therapeutic endoscope is recommended since the large diameter instrumentation channel allows for insertion of large diameter stents and accessories required for therapeutic interventions. The initial use of a sphincterotome for deep bile duct cannulation is recommended for several reasons. First, when it is anticipated that a sphincterotomy will be needed, exchange to a sphincterotome from another catheter is avoided. Second, it allows variable upward tip deflection in order to introduce the tip of the catheter into the biliary orifice; the tip deflection is then relaxed to achieve deep cannulation. Steerable catheters are comparably effective and safe for this technique but their additional use does not seem to be cost effective for routine use.1 Two previous randomized controlled trials showed success rates of 84% and 97%, respectively, for primary cannulation with sphincterotomes, which was superior to the use of standard catheters with no significant differences in safety.2,3

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Failures of cannulation with a standard catheter can frequently be overcome by crossover to a sphincterotome and a guidewire technique.4 Several previous studies and a meta-analysis showed that wire-guided cannulation may increase the success rates and lower adverse event rates.5,6 Recent randomized controlled trials confirmed that wire-guided selective cannulation of the bile duct appears to significantly shorten procedure and fluoroscopy times. However, neither the method nor the type of catheter used resulted in significant differences in either success rate or incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis.7,8 There are few data comparing cannulation with different sphincterotomes.5 Further details of cannulation of the major papilla are described in Chapter 13.

Instruments (see also Chapter 4)

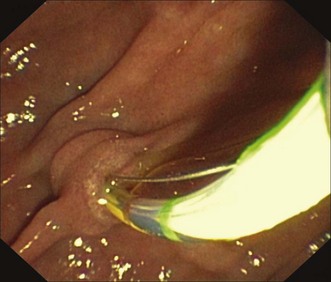

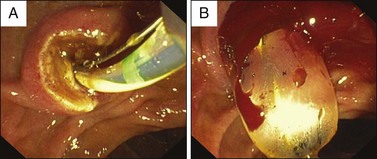

The type of the sphincterotome should be selected according to the individual anatomic situation and the preference of the endoscopist. Sphincterotomes differ in the diameter and length of the tip, length. and characteristics of the cutting wire and shaft stiffness that are described in detail in Chapter 4 and a recent review.5 Tapered devices, which require smaller wires (0.025 in or less), can be easier to insert into the papilla but are also more prone to cause tissue trauma and contrast infiltration than those with a more blunted tip. An ultrasmooth tapered rounded polished tip may overcome this potential problem (Fig. 16.1).

Modern sphincterotomes provide a lumen for insertion of a guidewire and an integrated hub for contrast injection. These devices allow repeated injection of contrast media without the need for guidewire removal. This approach can be very helpful in difficult cannulation or in targeting ductal strictures with the wire under cholangiographic guidance. Sphincterotomes with a preloaded guidewire are convenient for the assistant and may accelerate the cannulation. Devices that allow the use of short wires are additionally helpful since they reduce the over-the-wire exchange to a short part of the total device length while locking the wire, which may reduce the risk of losing access. In addition, they offer the option of guidewire manipulation by the endoscopist, which can be advantageous depending on the expertise of the operator and the assistant. A short, 15- to 20-mm cutting wire can be precisely controlled but it tends to draw the cutting direction toward the 2 o’clock position. Contact with the sphincter may be inadequate, thus making the cutting difficult in some situations. However, the advantage of shorter cutting wires over a 30-mm wire device is the reduced risk of an uncontrolled large cut when inserted too deep into the bile duct. In addition, the proximal part of a long cutting wire may come into contact with the elevator of the duodenoscope or overhanging duodenal folds; the former causes wire breakage when electrocautery current is applied. This problem can be overcome by use of a sphincterotome that is coated on the proximal part of the cutting wire. However, a recent prospective randomized controlled trial showed no significant differences between a partially covered and an uncovered sphincterotome in terms of bleeding rates or other adverse events.9 A thin monofilament wire provides a clean, sharp cut but may break more easily than a braided wire during application of electrocautery. On the other hand, braided wires are rarely used because they may induce more thermal injury. There are no formal trials that compare the efficacy and safety of these different devices. As experience grows, each endoscopist will develop preferences for a limited array of standard accessories depending on expertise, skill of assistants, and patient selection. The use of special sphincterotomes can be limited to particular cases. A thin device with a 4 Fr ultrataper tip is useful after failed cannulation using standard techniques in the setting of a small papilla, suspicion of a narrow ductal orifice, or difficulty in achieving proper cutting orientation. The latter problem can be overcome by the use of a rotatable sphincterotome. This instrument uses a specially designed handle that allows for controlled tip rotation. Sphincterotomes with a tip length of more than 5 mm can occasionally be helpful when there is difficult access to the papillary orifice as seen in patients with a juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum or altered surgical anatomy. Push-type or sigmoid-shaped sphincterotomes have been developed for ES in patients with Billroth II anatomy. Malfunction of sphincterotomes can infrequently occur but usually can be managed without major adverse events.5

Procedure

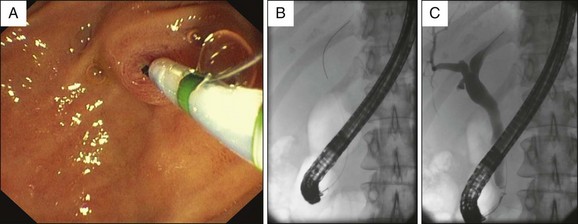

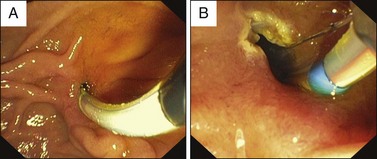

The papilla is usually approached with the sphincterotome from a distance so that its precurved distal part is evident upon exiting the endoscope. Alternatively, the tip of the sphincterotome is gently introduced into the papillary orifice. A short, straight position of the duodenoscope facilitates precise control of the device. Subsequent bowing of the tip usually allows its insertion toward 11 o’clock into the opening of the common bile duct (Fig. 16.2). Straightening the tip and gently withdrawing the endoscope results in further anchoring the tip of the device within the common bile duct. It can be then further advanced to achieve deep cannulation. Such a smooth, direct approach may fail and the procedure can become difficult and frustrating. Careful injection of contrast may allow visualization of the biliary anatomy for targeted guidance of the tip of the sphincterotome or insertion of a guidewire. However, repeated injections may induce edema of the papilla and increase the likelihood of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Alternatively, a guidewire can initially be gently passed in the direction of the bile duct under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance without contrast injection. For this approach, guidewires with a soft tip, preferably hydrophilic, should be used to reduce the risk of ductal injury (Fig. 16.3; Video 16.1). Cannulation of the bile duct with a sphincterotome with or without use of a guidewire should succeed in approximately 90% of cases. Failures are caused mainly by a difficult access to the papilla because of anatomic variations or previous gastroduodenal surgery. Ampullary tumors or impacted stones creating a bulging papilla can also impair the approach to the papillary orifice or deep ductal cannulation. For these cases, lifting the roof of the papilla with the adjustable tip of the sphincterotome and use of a hydrophilic guidewire are helpful in selective cannulation and controlled cutting.

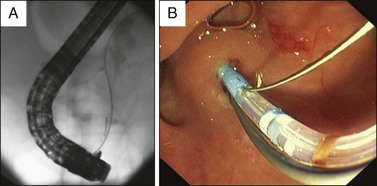

When cannulation fails, a variety of additional techniques have been established. In a case of unintended repeated cannulation of the main pancreatic duct, a guidewire with a hydrophilic tip can be inserted in the pancreas that may facilitate to straighten an angulated course of a common channel or the distal part of the common bile duct (Fig. 16.4; Video 16.2). The wire can then be locked for removal and reinsertion of the sphincterotome alongside the pancreatic duct wire for further attempts to cannulate the bile duct. Alternatively, a 5 Fr pancreatic stent can be placed to facilitate the biliary approach. If these techniques fail, a transpancreatic or precut sphincterotomy and, as a last option, a rendezvous procedure should be considered. Their appropriate use allows access to the biliary system in nearly all cases. However, the risk of adverse events increases in particular when “access” papillotomy is performed, which should therefore be limited to experienced endoscopists. Availability and local expertise will determine how long to persist in difficult biliary cannulation and when to switch to precut techniques. A recent meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials showed that in skillful hands the early implementation of precut and persistent cannulation attempts have similar overall cannulation rates. Early precutting seems to reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis but not the overall adverse event rate.10 Details are described in Chapters 7 and 14.

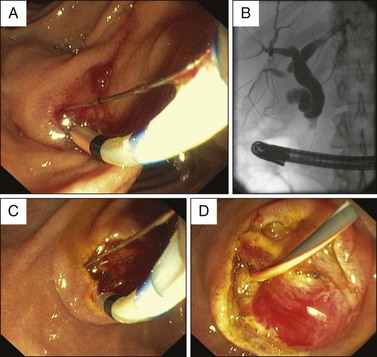

After deep cannulation has been confirmed by contrast injection, a guidewire should be advanced to the proximal biliary system in order to secure ductal access for subsequent maneuvers and exchange of accessories. The short wire technology allows locking the wire with the locking device attached to the duodenoscope. The tip of the sphincterotome is then slightly bowed so that it is in contact with the roof of the papilla. It should be considered that a stiff shaft of a deeply inserted guidewire can limit the extension of bowing of the cutting wire. This infrequent problem can be overcome by pulling the guidewire back until the flexible tip approaches the papilla without losing biliary access. Not more than 5 mm of the cutting wire should be inside the papilla so that only a small amount of tissue will be cauterized (Fig. 16.5, A). This approach improves the cutting action and avoids a rapid large incision (“zipper”), which can occur when pure cutting current is used. The use of newer electrosurgical generators has largely eliminated this adverse event. Most sphincterotomes have endoscopically visible markers at the distal part of the catheter that allow one to determine the depth of insertion of the cutting wire into the bile duct (Fig. 16.1 and 16.5, A). It is generally believed that orientation of the cutting wire in the range between the 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions reduces the likelihood of bleeding and perforation. In spite of great efforts by the accessory manufacturers to develop sphincterotomes with cutting wires that automatically cut along these directions, the devices may sometimes still orient in the 3 o’clock direction. A new modification of a rotatable sphincterotome seems to be helpful but needs further evaluation. For appropriate cutting direction, the papilla has to be placed on the left side and along the 10 or 11 o’clock position. This maneuver can be achieved by rotating the left-right dial to the left while advancing the duodenoscope slightly into the “long” endoscope position (Fig. 16.5, A and B; Video 16.1). Alternatively the endoscope can be carefully withdrawn, also with rotation to the left side.

The choice of electrosurgical current for ES is a source of controversy.11 The combination of high cutting current blended with a low coagulation current is most frequently used. Creation of edematous, extensively whitened or blackened tissue during ES is evidence of suboptimal cutting and may predispose to postprocedural pancreatitis or sphincter scarring. This problem increases when too much cutting wire is inside the papilla and/or the contact to the tissue of the papillary roof is inadequate. Previous trials suggested that pure-cut electrocautery current is safer than blended current in terms of post-ERCP pancreatitis without increasing the bleeding rate.12,13 However, a recent meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed the rate of post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients who underwent sphincterotomy when using pure current was not significantly different from those when mixed current was applied. Pure current was associated with more episodes of bleeding.14 In less experienced hands there may be an even higher risk of bleeding and perforation when a longer part of the cutting wire is inside the papilla, which can lead to a very fast uncontrolled large cut (“zipper” cut) when using pure current. A combined technique of beginning the incision using cutting current and finishing the incision using blended current was not associated with a decrease in the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis in a small trial.15 An alternative electrocautery option is the use of the “ENDO CUT” mode of the ERBE electrosurgical generator in which cutting and coagulation current are alternated by the intrinsic software. A similar technology has been introduced by other companies as well. A potential advantage of this method is a stepwise cutting action that allows precise control of the direction and length of the incision. This replaces the technique whereby current is applied in short pulses controlled by foot pedal activation, which is recommended for pure-cut or blended current to reduce the risk of a “zipper” cut. A large retrospective analysis suggested that microprocessor-controlled ES is associated with a significantly lower frequency of intraprocedural bleeding but had no impact on clinically evident hemorrhage.16

The size of ES can vary and depends on the diameter of the distal portion of the common bile duct as well as the indication for sphincterotomy. During cutting, pressure on the papillary roof is provided by upward lifting of the slightly bowed sphincterotome or its lifting by maneuvering the tip of the duodenoscope. ES should be continued only when the wire can be clearly seen and when it is directed between the 11 and 1 o’clock positions. Guidance and repositioning of the device should be mainly controlled with the tip and the shaft of the endoscope, which is maneuvered with the right hand of the operator like the handle of a knife. A small incision seems to be appropriate for placement of an endoprosthesis in malignant biliary obstruction, whereas complete splitting of the sphincter should be attempted for treatment of bile duct stones and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) to decrease the risk of recurrences and ES-related stenosis of the papilla (Fig. 16.5, C and D; Video 16.1). However, the correlation between the length of cutting and the incidence of early or late adverse events of ES has not been determined in formal trials. Biliary sphincterotomy should be limited to the junction between the duodenal wall and the intraduodenal portion of the papilla of Vater, which is sometimes difficult to determine since there is no reliable endoscopic “landmark.” The incision also should be finished if the inner lumen of the bile duct is completely visible or the bended tip of the sphincterotome can be pulled through the papilla without any resistance (Fig. 16.5, D). In view of modern techniques of lithotripsy and the option to combine ES with sphincteroplasty, a large hazardous ES is no longer required. If a wide opening to the common bile duct is needed, it may be safer to perform a small to moderate-sized incision and then dilate the orifice with a balloon catheter rather than to increase the size by cutting (Fig. 16.6; Video 16.3; see Chapter 17). Compared with other indications, the risk of adverse events of ES is usually low in patients with a dilated common bile duct and in the presence of ductal stones, especially when the papilla is large and protruding due to an impacted stone.

Extension of a previous biliary sphincterotomy may be required for the treatment of recurrent bile duct stones or recurrence of symptoms after SOD. The technique of ES in this setting does not differ from that when ES is performed initially (Fig. 16.7). Data from anecdotal reports and small case series were controversial regarding the risk of hemorrhage after extension of a previous ES and suggested that the incidence of bleeding was increased during a postsphincterotomy period of approximately 1 week due to a resultant increased vascularity. However, large prospective studies did not find that extension of a previous ES is an independent risk factor for hemorrhage.17,18 Nevertheless, the risk of severe bleeding or duodenal perforation should be considered. Although it may not be related to previous ES, the extension of the incision should be carefully and stepwise performed. Sphincteroplasty could be a safer alternative, at least in cases with a difficult orientation and control of the cutting wire.

ES in Patients with Difficult Anatomy

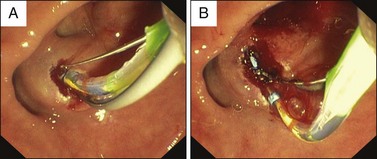

Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula are found in 10% to 15% of patients undergoing ERCP. Depending on the location of the papilla, cannulation of the bile duct can be difficult and may require special techniques such as insertion of the tip of the endoscope into the diverticulum, use of sphincterotomes with a long nose, or pulling the papilla out of a diverticulum with biopsy forceps or a second catheter. After successful deep cannulation it is strongly recommended that ES is performed over a guidewire. This approach facilitates cutting in the direction of the bile duct, which may otherwise be difficult to determine due to the altered anatomy. Moderate bending of the tip of the sphincterotome with a few millimeters of the cutting wire inside the papilla exposes the papillary roof to allow for a controlled incision. Any direction of the cutting wire toward the base of the diverticulum should be avoided (Fig. 16.8; Video 16.2). Data from a large, retrospective analysis suggested that bleeding after ES was an independent risk factor associated with juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula.19

Fig. 16.8 A, ES of a papilla inside a duodenal diverticulum (same case as Fig. 16.4); the sphincterotome is inserted over a guidewire to facilitate the cutting direction to the intradiverticular part of the papillary roof. B, Cutting could be extended for a few millimeters; depending on the indication for ES, combination with sphincteroplasty should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree