Chapter 88 BENIGN CYSTIC LESIONS OF THE VAGINA AND VULVA

Benign cystic lesions of the female external genitalia are frequently encountered in gynecologic and female urologic practices. True cystic lesions of the vagina and vulva originate from vaginal and vulvar tissues, respectively, but lesions arising from the urethra and surrounding tissues can appear as cystic lesions of the vagina and vulva as well. Most cysts of the female genitalia are located within the vagina, and their prevalence has been estimated to be 1 in 200 women; however, this figure is probably an underestimation, because most cysts are asymptomatic and therefore not reported.1 Cysts arising within the vulvar vestibulum are much less common.

Vaginal cysts typically occur in the third and fourth decades and are rarely found in prepubertal females except in countries where female circumcision in performed.2 Pradhan and Tobon reviewed the histology of 43 vaginal cysts over a 10-year period. In their study, the incidence of cyst types in decreasing order was müllerian cysts (44%), epidermal inclusion cysts (23%), Gartner’s duct cysts (11%), Bartholin’s gland cysts (7%), and endometriotic type (7%).3 The remaining types of cystic lesions include those of urethral or paraurethral origin and other rare lesions (Table 88-1).

Table 88-1 Vaginal Wall Cyst Location and Histology

| Diagnosis | Location | Histology |

|---|---|---|

| Müllerian (paramesonephric) cyst | Anywhere, usually anterolateral vaginal wall | Pseudostratified columnar, mucinous |

| Gartner’s (mesonephric) cyst | Same as müllerian cyst | Low columnar, nonciliated, nonmucinous |

| Skene’s (paraurethral) duct cyst | Floor of distal urethra | Stratified squamous |

| Bartholin’s gland cyst | Lateral introitus, medial to labia minora | Transitional or columnar, mucinous |

| Adenosis | Vaginal fornices and upper walls | Columnar, ciliated, mucinous |

| Cyst of canal of Nuck (hydrocele) | Superior to labia majora or inguinal canal | Flat cuboidal |

| Urethral caruncle | Urethral meatus | Loose connective tissue and vessels |

| Urethral diverticulum | Periurethral, anterior vaginal wall | Transitional or squamous epithelium |

| Inclusion cyst | Area of previous surgery | Stratified squamous epithelium around keratinous debris |

| Endometriosis | Anywhere, usually posterior fornix | Two of three: endometrial glands, stroma, hemosiderin-laden macrophages |

| Ectopic ureterocele | Periurethral | Transitional or squamous epithelium |

| Vaginitis emphysematosa | Upper two thirds of vagina | Inflammatory and giant cells |

| Hidradenoma | Interlabial sulcus | Papillomatous |

| Dermoid cyst | Paravaginal | Keratinized squamous epithelium and dermal appendages |

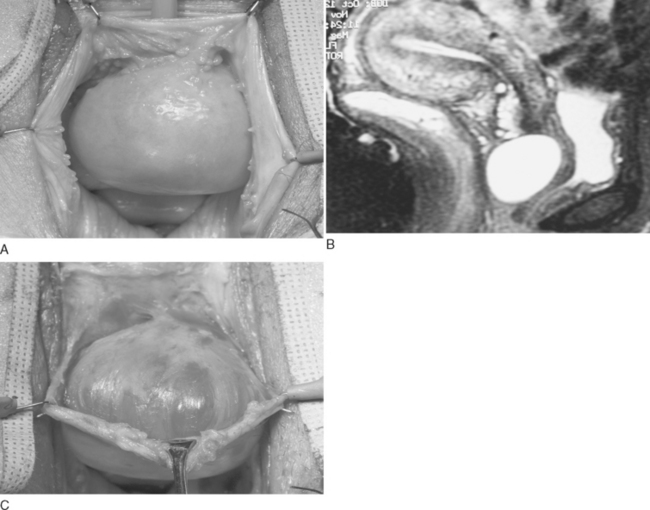

| Aggressive angiomyxoma | Vagina and vulva | Hypocellular, myxoid matrix of collagen and capillary-like vessels |

| Ciliated cyst | Anywhere in vagina, vulvar vestibulum | Müllerian-like columnar ciliated epithelium |

| Pigmented follicular cyst | Vulva | Stratified squamous epithelium with keratinization and pore |

PATIENT EVALUATION

During physical examination, the lesion should be assessed for location, mobility, tenderness, definition (smooth versus irregular), and consistency (cystic versus solid). The presence of malignancy must always be considered. Pelvic organ prolapse, such as cystocele or enterocele, can mimic a vaginal cyst and should be ruled out.

Pelvic imaging by means of ultrasound, voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required to characterize the lesion further (Fig. 88-1). Although each of these modalities has been useful in the diagnosis of vaginal cysts, pelvic MRI is the preferred modality for diagnosing both cystic lesions and a variety of other genitourinary abnormalities, including pelvic organ prolapse, urethral diverticula, ovarian abnormalities, and uterine pathology.

CYSTS OF EMBRYONIC ORIGIN

During the eighth week of embryologic development, the paired müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts fuse distally and develop into the uterus, cervix, and upper third of the vagina, which are lined by a pseudostratified columnar (glandular) epithelium. Wolffian (mesonephric) ducts normally regress in the female, and their remnants include Gartner’s duct, epoöphoron and paroöphoron. Beginning at week 12, a squamous epithelial plate derived from the urogenital sinus begins to grow upward and replace the original pseudostratified columnar epithelium with squamous mucosa. In addition to the lower two thirds of the vagina, the urogenital sinus derivatives in the female are Skene’s glands and Bartholin’s glands.4

Müllerian Cysts

During the process of replacement of the müllerian (pseudostratified columnar) epithelium with squamous epithelium of the urogenital sinus, müllerian epithelial tissue can persist anywhere in the vaginal wall, although it typically rests within the anterolateral wall. Consequently, müllerian cysts tend to be located along the anterolateral aspect of the vagina.5 Müllerian derivatives are the most common type of vaginal cyst; they are lined predominantly by mucinous epithelium but may be lined by any epithelium of müllerian origin: endocervical, endometrial, or fallopian.4,6 Clinically, the distinction between müllerian and mesonephric (Gartner’s duct) cysts is of little importance.

Müllerian cysts range in size from 1 to 7 cm.4 The great majority are asymptomatic and require no treatment. Occasionally, a müllerian cyst may become large enough that symptoms warrant excision.

Gartner’s Duct Cysts

Although it is clinically irrelevant to distinguish Gartner’s duct cysts from müllerian cysts, true Gartner’s duct cysts arise from vestigial remnants of the mesonephric (wolffian) ducts. Gartner’s duct extends from the mesosalpinx via the broad ligament to the cervix, so these cysts are usually located along the anterolateral vaginal wall.4,6 Typically, they are small, with an average diameter of 2 cm, but the cysts may enlarge to the point where they are mistaken for other structures, such as a cystocele or urethral diverticulum (Fig. 88-2A).4 The largest Gartner’s duct cyst reported was 16 × 15 × 8 cm.7

An association between Gartner’s duct cysts and abnormalities of the metanephric urinary system exists, and cases of ectopic ureter, unilateral renal agenesis, and renal hypoplasia have all been reported in association with Gartner’s duct cysts.8–10 Currarino reported on five children with a Gartner’s duct cyst and either ipsilateral renal hypoplasia or dysplasia,9 and Sheih and colleagues found that 6% of female children with unilateral renal agenesis had a Gartner’s duct cyst.10 Although such abnormalities usually present in childhood, awareness of this association should prompt the clinician to image the urinary tract when evaluating adults who present with Gartner’s duct cysts. MRI is especially useful, both for evaluation of the characteristics of the cyst and to rule out communication with the urinary tract (see Fig. 88-2B).

Gartner’s duct cysts are synonymous with simple cysts and are lined by cuboidal or low columnar, nonciliated, nonmucinous cells. They can be distinguished from müllerian cysts by the presence of a basement membrane and smooth muscle layer; however, clear distinction between the two can be made only on the basis of histochemical staining: müllerian cysts are periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and mucin positive, whereas mesonephric cysts are devoid of cytoplasmic mucicarmine or PAS-positive material.5,6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree