Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease

James E. Novak

Jerry Yee

INTRODUCTION

Anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and kidney transplantation, is a complex condition with important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Anemia is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as hemoglobin (Hb) < 13 g per deciliter in men and < 12 g per deciliter in women, and the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) recommends an evaluation when Hb is < 13.5 g per deciliter in men and < 12 g per deciliter in women.1 Nonetheless, a more precise characterization of anemia in CKD is problematic, and involves consideration of numerous hematologic, gastrointestinal, and hormonal abnormalities. In this chapter, we review the most recent evidence concerning the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of anemia in kidney disease. When applicable, we distinguish among CKD, ESRD, and transplant populations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of stages 1 through 4 CKD in the United States has been estimated at 13.1%, or about 40 million people.2 Anemia is common in CKD, and its prevalence increases as kidney function decreases. Claims data from the 2010 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) include a diagnosis of anemia in 43% of patients with stages 1 to 2 and 57% of those with stages 3 to 5 CKD.3 African Americans have correspondingly higher rates of 48% and 64% for stages 1 to 2 and 3 to 5 CKD, respectively. In contrast, anemia is present in 12% to 14% of subjects at risk for kidney disease (Kidney Early Evaluation Program [KEEP]) and only 5% to 6% of the general population (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES] 1999 to 2004).4

As of December 31, 2008, the combined hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) population in the United States was approximately 381,000 persons.3 Because the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) has decreased (see the following), the mean Hb of incident ESRD patients has fallen from approximately 10.5 g per deciliter in 2006 to 9.9 g per deciliter in 2008. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) target Hb of 11 to 12 g per deciliter, established in 2007, was achieved by only 37% to 38% of prevalent dialysis patients in 2008.3 Even considering 6-month rolling averages, this target was consistently achieved by < 50% of HD patients.5

Hb variability, defined as the spontaneous change in Hb concentration above or below the desired range with time, is common in CKD and ESRD patients.6 In the HD population, the standard deviation (SD) of Hb levels around the mean is 1.1 to 1.3 g per deciliter, and only 8% to 18% of patients maintain stable Hb over 6 to 12 months.7 In contrast, in the general population, the SD of Hb levels is < 0.6 g per deciliter. This variability may8,9,10 or may not11 have important implications for morbidity and mortality in CKD and ESRD patients (see the following). Hb also varies normally with age, sex, and race, as well as under the influence of infection, inflammation, other comorbidities, and HD parameters such as adequacy and water quality.6,12

In patients with CKD, anemia is associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and higher rates of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), congestive heart failure (CHF), major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and progression to ESRD.13 In a cohort of > 1300 men without clinical history of CHF, the presence of both Hb < 13 g per deciliter and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, compared to either anemia or CKD alone, was associated with a significantly higher rate of previously unrecognized LV dysfunction (ejection fraction [EF] < 40%).14 Rates of CHF hospitalization and death were 3 to 5 times higher in the group with anemia and CKD compared to the group with neither anemia nor CKD. Among European HD patients (Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study [DOPPS]), the relative risk (RR) for hospitalization and death increased by 4% and 5%, respectively, with each 1 g per deciliter decrease in Hb within the 10 to 13 g per deciliter range.15 Consistent with these data, in a recent study of HD patients from the United Kingdom Renal Registry, the relative hazard for death increased by nearly threefold with each 1 g per deciliter decrease in Hb within the 9 to 13 g per deciliter range.16 Among U.S. PD patients, the hazard ratio

(HR) for hospitalization and death increased similarly with decreased Hb within the same range.17

(HR) for hospitalization and death increased similarly with decreased Hb within the same range.17

Anemia is increasingly recognized as a major cause of signs and symptoms previously attributed to uremia, including fatigue, weakness, dizziness, cold intolerance, shortness of breath, decreased exercise tolerance, and decreased muscle strength.6,18,19 Anemia in CKD is also associated with functional and mobility impairment, increased risk of falls, and decreased health-related quality of life (QOL).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anemia: Historical Overview

The Bible and ancient medicine portrayed blood as a symbol of life, and most physical and mental disease was attributed to disorders of the blood.20 The first xenogeneic (animal-tohuman) blood transfusion was reported in Paris in 1667. Physician-in-Ordinary to Louis XIV, Jean-Baptiste Denis, and surgeon Paul Emmerez transfused whole lamb blood into a patient who had previously been bled 20 times for fever, whose symptoms of anemia improved markedly following the procedure. The first successful allogeneic (human-tohuman) blood transfusion was reported in London in 1825, when James Blundell transfused a man’s blood into his wife to treat postpartum hemorrhage.20

The idea that the bone marrow is the site of erythropoiesis in response to hypoxia was first proposed in 1823 and gradually expanded during the following century.20,21,22 In 1863, Jourdanet observed that blood viscosity was higher in Mexicans living at high altitudes than in those living at sea level.23 In 1891, Viault extended this observation to red blood cell (RBC) counts in Peruvians.24 Carnot and DeFlandre25 reported in 1906 that serum from bled rabbits, when injected into normal rabbits, stimulated RBC production. They tentatively coined the term “hemopoietine” to identify the presumed erythropoietic substance transferred by the serum. Similar experiments, in which serum or plasma from anemic or hypoxemic rabbits caused a reticulocytosis in recipient rabbits, were conducted from 1932 to 1953.22 Brown and Roth26 determined in 1922 that the anemia of chronic nephritis resulted from hypoactive bone marrow. In 1950, Reissmann27 used parabiotic rats to show that, although only one animal was exposed to low O2 tension, both partners exhibited bone marrow erythroid hyperplasia, reticulocytosis, and polycythemia, again strongly suggesting the presence of a humoral erythropoietic factor acting on the bone marrow. In 1948, Bonsdorff and Jalavisto27a named this factor erythropoietin (EPO).

In subsequent years, the tissue origin of EPO was elucidated. In 1957, it was shown that a bilateral nephrectomy prevented the rise in plasma EPO levels in bled rats.28 Experiments from 1961 to 1974 showed that perfusates from hypoxic rabbit and dog kidneys could stimulate presynthesized EPO release and subsequent reticulocytosis.21,22 In 1983, EPO mRNA from hypoxic rat kidneys, injected into frog oocytes, was translated into EPO, and experiments from 1988 to 1996 demonstrated EPO transcripts and biologically active EPO in the peritubular interstitial cells of kidneys from a number of species.29

More recent discoveries have included the description of EPO physiology and molecular biology, especially pertaining to kidney disease. Erythropoietic activity was quantified from 1955 to 1961 by the measurement of increased 59Fe uptake by RBCs in polycythemic rats and in normal rats that had been injected with plasma from anemic rats.30,31 The inverse relationship between EPO concentration and hematocrit was reported in 1968.32 EPO itself was ultimately purified in 1977 by concentrating 2550 L of urine from patients with aplastic anemia.33 Isolation of the purified protein facilitated the development of an EPO radioimmunoassay in 1979,34 followed by the cloning and expression of the EPO gene in 1985.34,35 Clinical trials of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO), which showed improved Hb in ESRD patients, were conducted from 1986 to 1987, thereby ushering in the era of ESA therapy for the anemia of CKD.36,37

Normal Erythropoiesis

Tissue hypoxia, primarily in the kidney, provides the major physiologic stimulus for RBC production. Importantly, a fall in renal blood flow (RBF) is coupled with a decrease in GFR, which leads to reduced oxygen use by tubule transport proteins. Thus, tissue oxygenation is relatively independent of RBF across a wide range.38,39

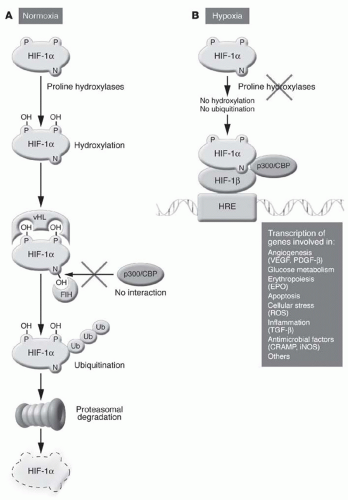

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are helix-loop-helix heterodimeric transcription factors that consist of O2-regulated α subunits and constitutively expressed β subunits.39 In normoxic cells, O2, Fe2+, and ascorbic acid activate prolyl-4-hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins, which catalyze the hydroxylation of key proline residues in HIF-α subunits.40,41 HIF-α then binds the von Hippel-Lindau protein, is polyubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin ligase, and then is swiftly degraded by the proteasome.20,42 Conversely, in hypoxic cells, low O2 tension and high concentrations of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates inhibit PHD proteins, allowing HIF-α to translocate to the nucleus, heterodimerize, and activate hypoxia response elements (HREs) that regulate gene transcription for numerous cellular processes, including erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, and anaerobic metabolism (Fig. 76.1).

Of the three HIF proteins currently known, HIF-2 is the most strongly implicated in the hypoxic induction of EPO.39,42 HIF-2α knockout mice are pancytopenic with bone marrow hypocellularity and attenuated EPO levels; RBC production normalizes with the addition of recombinant EPO.43 In addition, the postnatal deletion of HIF-2 abolishes EPO production by the kidney and liver, and overexpression of HIF-2 causes erythrocytosis.44 HIF-2-mediated EPO transcription may require the cooperative binding of other transcription factors, such as hepatocyte nuclear factor 4, to the HREs.45 HIF-1, on the other hand, is more important in regulating glycolysis, whereas some HIF-3 splice

variants may actually inhibit transcription.39 Interestingly, the HIF proteins activate the transcription of PHD-2 and PHD-3, thereby creating a negative feedback loop resulting in their own degradation.

variants may actually inhibit transcription.39 Interestingly, the HIF proteins activate the transcription of PHD-2 and PHD-3, thereby creating a negative feedback loop resulting in their own degradation.

EPO is a 165-amino acid (AA) glycoprotein hormone with a molecular weight of 30 kDa.39 In adults, 90% of the EPO produced in response to anemia originates from the kidney, specifically from a population of cortical peritubular fibroblasts with neuronlike morphology in the inner cortex and the outer medulla, regions that tend to be especially susceptible to hypoxia.46 EPO expression in other cell types is normally suppressed by transcription factors that bind to the tetranucleotide sequence, G-A-T-A, in the core promoter region of the gene (GATA transcription factors). Mild hypoxia, rather than increasing the transcription of EPO messenger RNA (mRNA), actually stimulates the brisk recruitment of previously quiescent clusters of cells within the kidney, each of which then generates EPO at a fixed rate. Moderate hypoxia, however, fuels additional EPO production by the liver, mainly from hepatocytes near the central veins and, to a lesser extent, from stellate or Ito cells.39,46 EPO transcripts have also been isolated from bone marrow, the spleen, the brain, the lungs, hair follicles, and the reproductive tract, but are unlikely to contribute significantly to plasma EPO levels, because protein expression by these tissues has not been demonstrated.20

The erythropoietin receptor (EPO-R) is a 484-AA glycoprotein with a single membrane-spanning domain that homodimerizes during synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum.20,47 Each EPO-R binds to the tyrosine kinase, Janus kinase-2 (JAK-2), and the entire complex associates with the type 2 transferrin receptor (TfR-2) for trafficking to the cell membrane. TfR-2, a disulfide-bonded homodimer, is required to optimize the sensitivity of the EPO-R complex to circulating EPO and to efficiently synthesize growth differentiation factor (GDF)-15 (see the following).47 Parenthetically, the Friend spleen focus-forming virus glycoprotein (gp55), a very different disulfide-bonded homodimer, can substitute for TfR-2 in facilitating EPO-R homodimerization and trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in EPO-independent EPO-R activation, autonomous erythroid proliferation, and leukemia in mice. Under normal conditions, the EPO-R:TfR-2 complex, upon binding EPO, undergoes a conformational change that allows its cytoplasmic domains to be tyrosine phosphorylated by JAK-2, stimulating signal transduction and activator of transcription (STAT)-5, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI-3K), and protein kinase C (PKC).39,48 The acute effects of EPO last only 30 to 60 minutes, after which JAK-2 and the EPO-R are dephosphorylated and the EPO:EPO-R complex may be internalized and degraded by the proteasome.49 In addition, EPO also activates the phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP-1, which binds to the EPO-R, dephosphorylates JAK-2, and terminates the propagation of the other intracellular signals. However, the primary signaling cascade set in motion by EPO-R activation is critical for the synthesis of erythrocytes.

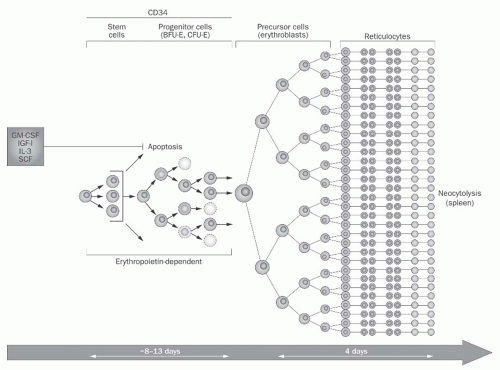

Erythropoiesis takes place in the bone marrow, which is unquestionably the principal target of EPO activity. RBC production begins with the EPO-independent differentiation of the multipotent hematopoietic stem cell into the colony-forming unit granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM), which in turn develops into the burst-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E).50 The BFU-E is the first cell type in the erythroid lineage to express the EPO-R, and EPO is required for its survival and subsequent proliferation into several colony-forming units erythroid (CFU-E), a process that requires 10 to 13 days (Fig. 76.2). Of all the

erythroid precursors, the CFU-E has the highest membrane density of EPO-Rs, albeit < 1000 per cell, and additionally expresses TfR and GATA-1.51 In the presence of EPO, GATA-1 promotes transcription of the antiapoptotic protein bcl-xL, which allows the CFU-E to multiply. Conversely, in the absence of EPO, proapoptotic caspases are activated, and the CFU-E dies. A host of other growth factors, such as interleukin (IL)-3 and IL-9; granulocyte-colony stimulating factors and granulocyte, monocyte-colony stimulating factors (G-CSF and GM-CSF); and stem cell factors (SCFs) are also required for CFU-E proliferation.50

erythroid precursors, the CFU-E has the highest membrane density of EPO-Rs, albeit < 1000 per cell, and additionally expresses TfR and GATA-1.51 In the presence of EPO, GATA-1 promotes transcription of the antiapoptotic protein bcl-xL, which allows the CFU-E to multiply. Conversely, in the absence of EPO, proapoptotic caspases are activated, and the CFU-E dies. A host of other growth factors, such as interleukin (IL)-3 and IL-9; granulocyte-colony stimulating factors and granulocyte, monocyte-colony stimulating factors (G-CSF and GM-CSF); and stem cell factors (SCFs) are also required for CFU-E proliferation.50

Subsequent phases of erythroid differentiation take place within erythroblastic islands.51 Each erythroblastic island is a distinct, erythropoietic unit that consists of one central macrophage closely apposed to several maturing erythroblasts. Cell-specific molecular interactions, such as the binding between β1 integrins and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, are critical to maintain the structure of these islands.52 The CFU-E first differentiates into the proerythroblast, which again requires exposure to EPO to escape apoptosis. The proerythroblast has a large nucleus and expresses numerous membrane adhesion molecules such as CD44, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, and α4β1 and α5β1 integrins.53 During maturation, the nucleus condenses and adhesion molecule expression is greatly diminished. Of note, CD44, the expression of which decreases by 30-fold during the progression from the proerythroblast to the orthochromatic normoblast, may be a more reliable marker of erythroid differentiation than the commonly used TfR, the expression of which remains relatively constant.

Terminal erythroid differentiation occurs as the erythroblast progresses through the basophilic, polychromatic, and orthochromatic normoblast stages. During this sequence, the cell acquires Hb, Rh factor, and the Duffy antigen, as well as skeletal proteins such as α– and β-spectrin, ankyrin, proteins 4.1R and 4.2, and the band 3 glycoprotein, which promotes membrane elasticity and stability.53 The orthochromatic normoblast extrudes its pyknotic nucleus, which is ingested by the central macrophage and digested by deoxyribonuclease II, and becomes a reticulocyte.51 This enucleated, multilobed reticulocyte is transformed into a biconcave erythrocyte during the next 2 to 3 days, initially in the bone marrow and then in the circulation, a process that involves membrane vesiculation, stabilization, and reorganization, as well as decreased cell volume. During erythrocyte maturation, cell membrane concentrations of aquaporin-1 (AQP-1), the glucose transporter (GLUT-4), the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE-1), and the Na+/K+ pump are decreased, whereas the membrane skeletal proteins are retained.54

The Importance of Iron

Iron is essential for normal erythropoiesis. Total body iron is 50 mg per kilogram of body weight, or approximately 3500 mg for a 70-kg man.55 This iron is distributed as about 65% in Hb; 10% in myoglobin (Mb), cytochromes, and enzymes; and the remainder in the reticuloendothelial system (RES), liver, and bone marrow. To meet the daily requirement of 300 billion fresh erythrocytes, differentiating erythroblasts need approximately 20 to 30 mg per day of iron, most of which is obtained from the recycling of senescent RBCs by phagocytic macrophages of the RES.56 Heme from these cells is metabolized by heme oxygenase, and the Fe2+ released is sequestered by ferritin, which itself may undergo lysosomal degradation to hemosiderin.55 The central macrophage of the erythroblastic island, acting as a “nurse cell,” releases ferritin to its satellite erythroblasts, thus facilitating Hb synthesis and uninterrupted differentiation.54

Ferritin is indispensable for concentrating iron to the levels required for iron/oxygen chemistry, including aerobic metabolism, while avoiding the generation of insoluble ferric oxide and toxic oxygen radicals.57 Ferritin is a hollow sphere with an external diameter of 12 nm and molecular weight of 480 kDa, consisting of 24 heavy and light polypeptide chains folded into four-helix bundles.58 The center of the molecule’s cavity has an internal diameter of ˜7 to 8 nm, accessible via eight protein pores, which can accumulate up to 4000 atoms of iron. Iron must be reduced to Fe2+ to travel through the pores to the interior of the ferritin molecule, where it undergoes ferroxidase-catalyzed conversion to Fe3+ for storage.57 Sequestration by ferritin increases the effective solubility of iron by 15 orders of magnitude.

Although only 1 to 2 mg per day of iron is obtained from the diet, gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of iron is required to offset minor losses from epithelial desquamation and microscopic bleeding.56 The typical dietary intake of iron is 15 to 20 mg per day. Only 10% of dietary iron is present as relatively bioavailable heme compounds, which are readily absorbed into enterocytes and degraded by heme oxygenase to release Fe2+. The remaining nonheme iron exists in the relatively unavailable Fe3+ state and must be reduced to Fe2+ by ferrireductase in conjunction with ascorbic acid; iron is then transported into the enterocyte by divalent metal transporter (DMT)-1.55,59

Cytosolic iron, whether present in duodenal enterocytes, macrophages, or hepatocytes, is delivered to the circulation via ferroportin (FP)-1, oxidized to Fe3+, and bound to plasma transferrin.60 In order to provide sufficient iron for reticulocyte production, transferrin-bound iron must be recycled 6 to 7 times daily.7 Iron enters the erythroblast when two transferrin molecules bind TfR-1, which then undergoes endocytosis into a clathrin-coated siderosome.55 The siderosome is acidified, releasing Fe3+ that is again reduced to Fe2+ by ferrireductase and exported to the cytoplasm via DMT-1. The apotransferrin:TfR-1 complex is recycled to the cell membrane and released into the circulation.60 Meanwhile, cytosolic iron enters the mitochondrion, where ferrochelatase catalyzes its insertion into protoporphyrin IX to form heme, the critical component of Hb.55,61

Iron homeostasis is largely regulated at the level of GI absorption. One regulatory model postulates that plasma iron is sensed by duodenal crypt enterocytes via the TfR.55 When iron is scarce, low cytosolic iron induces the transcription of

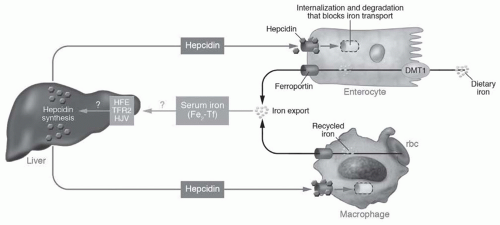

TfR-1, DMT-1, and FP-1 mRNA, all of which stimulate iron absorption. A second, compatible model proposes that iron absorption is downregulated by hepcidin, a 25-AA polypeptide produced by hepatocytes when iron is abundant. Hepcidin binds to FP-1 in enterocytes, macrophages, and hepatocytes themselves, promoting the JAK-2-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation, internalization, and degradation of FP-1; thus, hepcidin inhibits both the efflux of iron from the duodenum into the plasma as well as the mobilization of iron from the RES.62 Hepcidin expression is itself regulated at critical points in the homeostatic loop. Specifically, hepcidin transcription is inhibited by HIF during tissue hypoxia, by soluble hemojuvelin during iron deficiency, and by EPO, GDF-15, and twisted gastrulation (TWSG-1) during erythroblast maturation. Conversely, hepcidin transcription is stimulated by iron-mediated production of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), lipopolysaccharide, and IL-6 in states of systemic inflammation.55,56,63,64 The biology of hepcidin is summarized in Figure 76.3.

TfR-1, DMT-1, and FP-1 mRNA, all of which stimulate iron absorption. A second, compatible model proposes that iron absorption is downregulated by hepcidin, a 25-AA polypeptide produced by hepatocytes when iron is abundant. Hepcidin binds to FP-1 in enterocytes, macrophages, and hepatocytes themselves, promoting the JAK-2-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation, internalization, and degradation of FP-1; thus, hepcidin inhibits both the efflux of iron from the duodenum into the plasma as well as the mobilization of iron from the RES.62 Hepcidin expression is itself regulated at critical points in the homeostatic loop. Specifically, hepcidin transcription is inhibited by HIF during tissue hypoxia, by soluble hemojuvelin during iron deficiency, and by EPO, GDF-15, and twisted gastrulation (TWSG-1) during erythroblast maturation. Conversely, hepcidin transcription is stimulated by iron-mediated production of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), lipopolysaccharide, and IL-6 in states of systemic inflammation.55,56,63,64 The biology of hepcidin is summarized in Figure 76.3.

A third model of iron regulation involves host defense pathways. Under conditions of infection or inflammation, macrophages generate DMT-1 and neutrophils release apolactoferrin and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), all of which remove iron from the circulation and decrease its availability to iron-dependent microorganisms.60 NGAL is a 25-kDa protein, which similarly to hepcidin, sequesters iron during the acute phase response.65 NGAL binds siderophores, high-affinity iron chelators produced by bacteria, and also functions as a nontransferrin pool of circulating iron.66 During the acute phase response, cytokines such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α also stimulate the translation of presynthesized ferritin subunit transcripts.58 Presumably, this ferritin-mediated iron trapping is protective in states of acute inflammation, such as bacterial infection, but maladaptive in states of chronic inflammation, such as CKD.

FIGURE 76.3 Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Dietary iron uptake into the enterocyte involves transit via the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). Iron recycled from senescent red blood cells (rbc) is stored in macrophages. Under conditions of iron sufficiency, increased diferric transferrin (Fe2-Tf) is sensed by the human hemochromatosis (HFE) protein, type 2 transferrin receptor (TFR2), and the hemojuvelin (HJV) protein, and stimulates hepcidin production. Hepcidin binds to its ligand, ferroportin, and internalizes it back into the cytoplasm of enterocytes and macrophages, thereby sequestering iron and inhibiting its export from these cells. (Reproduced with permission from Vaulont S, Lou D-Q, Viatte L, et al. Of mice and men: the iron age. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2079.) (See Color Plate.) |

Lastly, iron availability may regulate its own use via iron-regulatory elements (IREs). When cytosolic iron is abundant, transcription factors known as iron-regulatory proteins (IRPs) are rendered unable to bind their IRE; specifically, IRP-1 is converted into an aconitase and IRP-2 is degraded by the proteasome.39,67 On the other hand, when iron is absent, IRPs bind to 3′- or 5′-regions of specific coding sequences, stimulating or inhibiting transcription, respectively. The IRP/IRE complex increases the transcription and translation of TfR-1 and DMT-1, promoting iron uptake into cells. Conversely, IRP/IRE decreases the expression of ferritin, which prevents iron sequestration; HIF-2α, which prevents EPO synthesis; and δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase 2, which prevents heme synthesis. Thus, scarcity of cytosolic iron blocks erythropoiesis and further iron consumption.68

Mechanisms of Anemia in Kidney Disease

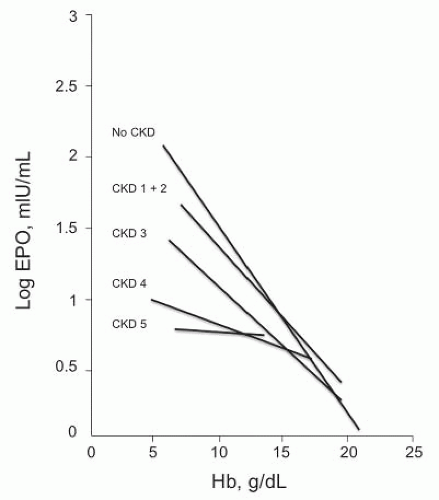

The anemia of CKD and ESRD is the result of a confluence of many pathophysiologic processes. The most well-known of these is a deficiency of EPO relative to the degree of anemia. In subjects with normal Hb and kidney function, the EPO concentration is roughly 3 to 30 mU per milliliter,

which increases by 100-fold as Hb falls.69 In patients with kidney disease, the inverse relationship between EPO and Hb evaporates as kidney function declines, with little correlation at GFR or creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 30 to 40 mL per minute (Fig. 76.4).69,70 In stages 4 through 5 CKD, this sluggish EPO response produces a normochromic, normocytic anemia.

which increases by 100-fold as Hb falls.69 In patients with kidney disease, the inverse relationship between EPO and Hb evaporates as kidney function declines, with little correlation at GFR or creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 30 to 40 mL per minute (Fig. 76.4).69,70 In stages 4 through 5 CKD, this sluggish EPO response produces a normochromic, normocytic anemia.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for relative EPO deficiency in advanced CKD. (1) The diseased kidney adapts to an increased single-nephron sodium load by attenuating tubular sodium absorption. This change decreases O2 consumption, improves oxygenation in the outer medulla, and reduces the stimulus for EPO production.69 (2) EPO secreted into the circulation may be neutralized by soluble EPO-R, a 27-kDa splice variant identified in dialysis patients, the transcription of which is induced by inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6 and TNF-α.71 (3) EPO may be inactivated by desialylation, a process mediated by proteases, the activity of which is increased in uremic patients.72 (4) Even if EPO does reach the bone marrow intact and in sufficient quantity to stimulate erythropoiesis, its action may be blunted by the absence of permissive factors, such as IL-3, calcitriol, and CD4 cells, as well as by the presence of inhibitory factors, such as polyamines, ribonuclease, and parathyroid hormone (PTH).72,73

Iron deficiency, both absolute and relative, contributes significantly to anemia in kidney disease. Absolute iron deficiency is caused by blood loss, such as from repeated phlebotomy, colonic angiodysplasias, and occasionally, uremic bleeding. HD patients can also lose blood in the dialysis circuit, with cumulative iron losses averaging 1 to 3 g per year.64 In addition, oral (PO) iron is poorly absorbed in advanced CKD, both because of hepcidin (see the following) as well as because of concomitantly prescribed medications such as proton pump inhibitors and calcium-, aluminum-, and lanthanum-containing compounds.74

Relative, or functional, iron deficiency occurs when the body is unable to mobilize otherwise adequate iron stores for erythropoiesis, a condition chiefly attributed to hepcidin. Hepcidin accumulates with progressive CKD, from 73 ng per milliliter in controls to 270 ng per milliliter in stages 2 through 4 CKD to 652 ng per mL in stage 5 CKD.75 This increase probably results from a combination of persistent inflammation, frequent iron administration, and decreased renal clearance of hepcidin.61,64 Interestingly, although anemia, hypoxia, the use of ESAs, and clearance by HD would be expected to decrease hepcidin levels, factors that induce hepcidin transcription clearly predominate. As previously mentioned, hepcidin binds to FP-1 and inhibits both the absorption of iron from the duodenum as well as the mobilization of iron from ferritin in the RES. NGAL, as well as hepcidin, is increased in HD patients and may contribute to functional iron deficiency.76

Iron deficiency is associated with reactive thrombocytosis in CKD and ESRD.7 One mechanism to explain this effect involves the sequence homology between thrombopoietin and EPO.77 As iron becomes scarce, EPO levels rise to compensate; in addition, patients may be given ESAs therapeutically. These high concentrations of either endogenous or exogenous hormone may accordingly stimulate platelet production. Thrombocytosis in response to iron deficiency, occasionally > 1,000,000 platelets per microliter, can be complicated by thromboembolic events, such as ischemic stroke, venous thromboembolism, central retinal vein occlusion, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.78,79

In patients with advanced CKD and ESRD, erythrocytes undergo accelerated destruction, a process that involves both young (neocytolysis) and old (senescence) RBC. Ironpoor, hypochromic cells are broken down during nadirs in EPO levels and undergo early phagocytosis because of abnormally high expression of phosphatidylserine.80 The RBC cell membrane in HD patients is poorly deformable and lipid peroxidated, with unusual proportions of spectrin, ankyrin, protein 4.1, and band 3.80

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree