Chapter 7 Adverse Events of ERCP

Prediction, Prevention, and Management

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has evolved from a diagnostic modality to a primarily therapeutic procedure for pancreatic as well as biliary disorders. ERCP alone or with associated biliary and pancreatic instrumentation and therapy can cause a variety of short-term adverse events, including pancreatitis, hemorrhage, perforation, cardiopulmonary events, and others (Box 7.1). These adverse events can range from minor—with one or two additional hospital days followed by full recovery—to severe and devastating—with permanent disability or death. Adverse events may cause the endoscopist significant anxiety and exposure to medical malpractice claims.

Major advances in the approach to adverse events of ERCP have occurred in several areas: standardized consensus-based definitions of adverse events,1 large-scale multicenter multivariate analyses that have allowed clearer identification of patient and technique-related risk factors for adverse events,2–9 and introduction of new devices and techniques to minimize the risks of ERCP.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Definitions of Complications, Adverse Events, Unplanned Events and Other Negative Outcomes

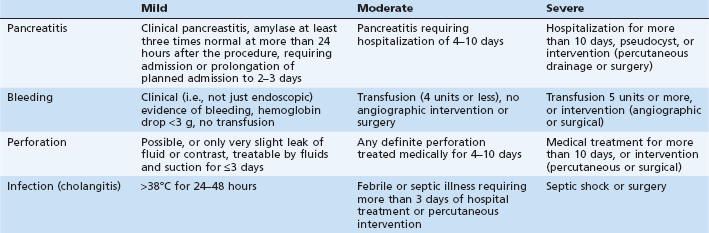

In 1991 standardized consensus definitions for complications of sphincterotomy were introduced1 and are still widely used (Table 7.1). Severity is graded primarily on number of hospital days and type of intervention required to treat the complication. This classification allows uniform assessment of outcomes of ERCP and sphincterotomy in various settings. Beyond immediate complication, there is an increasing awareness of the entire spectrum of negative (as well as positive) outcomes, including technical failures, ineffectiveness of the procedure in resolving the presenting complaint, long-term sequelae, costs, extended hospitalization, and patient (dis)satisfaction. Accordingly, the terminology has evolved from complications to adverse events, and more recently to unplanned events. The term adverse event is used throughout this book. Adverse events must be viewed in the context of the entire clinical outcome: a successful procedure with a minor or even a moderate adverse event may sometimes be a preferable outcome to a failed procedure attempt without any obvious adverse event. Failure at ERCP usually leads to a repeated ERCP or to an alternative percutaneous or surgical procedure that may result in significant additional morbidity, hospitalization, and cost.

Analyses of Adverse Event Rates

Reported adverse event rates vary widely, even between prospective studies. In two large prospective studies, pancreatitis rates ranged between 0.74% for diagnostic and 1.4% for therapeutic ERCP, respectively, in one study7 compared with 5.1% (about 7 times higher) for diagnostic ERCP and 6.9% (5 times higher) for therapeutic ERCP in another prospective study.3 Reasons for such variation include (1) definitions used; (2) thoroughness of detection; (3) patient-related factors; and (4) procedural variables, such as use of pancreatic stents, or extent of therapy. For all of these reasons, it should not be assumed that a lower adverse event rate at one center necessarily reflects better quality of practice.

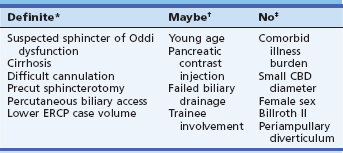

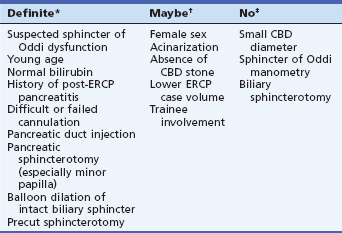

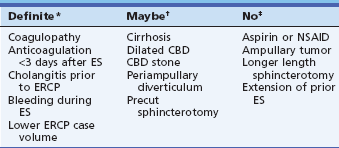

Most recent studies have used multivariate analysis as a tool to identify and quantify the effect of multiple potentially confounding risk factors, but these are not infallible as many potentially key risk factors were not examined in most studies, and some are overfitted (too many predictor variables for too few outcomes). Only a limited number of studies have included more than 1000 patients. Tables 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4 show summaries of risk factors for adverse events of ERCP and sphincterotomy based on published multivariate analyses.

Table 7.2 Risk Factors for Overall Adverse Events of ERCP in Multivariate Analyses

*Significant by multivariate analysis in most studies.

†Significant by univariate analysis only in most studies.

Table 7.3 Risk Factors for Post-ERCP Pancreatitis in Multivariate Analyses

*Significant by multivariate analysis in most studies.

†Significant by univariate analysis only in most studies.

Table 7.4 Risk Factors for Hemorrhage after Endoscopic Sphincterotomy in Multivariate Analyses

CBD, Common bile duct; ES, endoscopic sphincterotomy; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

*Significant by multivariate analysis in most studies.

†Significant by univariate analysis only in most studies.

Overall Adverse Events of ERCP and Sphincterotomy

Most prospective series report an overall short-term adverse event rate for ERCP and/or sphincterotomy of about 5% to 10%.2–9 Traditionally there has been a particularly high rate of adverse events for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (up to 20% or more, primarily pancreatitis, with up to 4% severe adverse events) and a very low adverse event rate for routine bile duct stone extraction, especially in tandem with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (less than 5% in most series).2 Sphincterotomy bleeding occurs primarily in patients with bile duct stones, and cholangitis mostly in patients with malignant biliary obstruction.

Summaries of multivariate analyses of risk factors for overall adverse events of ERCP and sphincterotomy are shown in Table 7.2. Although relevant studies are heterogeneous and sometimes omit potentially key risk factors, several patterns emerge (Table 7.2):

1. Indication of suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction was a significant risk factor whenever examined.

2. Technical factors, likely linked to the skill or experience of the endoscopist, were found to be significant risk factors for overall adverse events. These technical factors include difficult cannulation, use of precut or “access” papillotomy to gain bile duct entry, failure to achieve biliary drainage, and use of simultaneous or subsequent percutaneous biliary drainage for otherwise failed endoscopic cannulation. In turn, the ERCP case volume of the endoscopists or medical centers, when examined, has almost always been a significant factor in adverse events by both univariate or multivariate analysis.2–9

3. Death from ERCP is rare (less than 0.5%) but has most often been related to cardiopulmonary adverse events, highlighting the need for the endoscopist to pay attention to issues of safety during sedation and monitoring.

Notably, risk factors found not to be significant are the following: (1) older age or increased number of coexisting medical conditions—on the contrary, younger age generally increases the risk by both univariate and multivariate analysis; (2) smaller bile duct diameter, in contrast to previous observations; and (3) anatomic obstacles such as periampullary diverticulum or Billroth II gastrectomy, although they do increase technical difficulty for the endoscopist.2–9

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is the most common adverse event of ERCP, with reported rates varying from 1% to 40%, with a rate of about 5% being most typical.2–9 In the consensus classification, pancreatitis is defined as a clinical syndrome consistent with pancreatitis (i.e., new or worsened abdominal pain) with an amylase at least three times normal at more than 24 hours after the procedure, and requiring more than one night of hospitalization (Table 7.1).1 Some events are difficult to classify in the consensus definitions, such as patients with postprocedural abdominal pain and elevation of amylase to just under three times normal, or those with serum lipase more than three times normal with less than three times elevation of amylase, or those with dramatic enzyme elevations but minimal symptoms that are not clearly suggestive of clinical pancreatitis. There are many potential mechanisms of injury to the pancreas during ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES): mechanical, chemical, hydrostatic, enzymatic, microbiologic, and thermal. Although the relative contribution of these mechanisms to post-ERCP is not known, recent multivariate analyses have helped to identify the clinical patient and procedure-related factors that are independently associated with pancreatitis.

Patient-Related Risk Factors for Post-ERCP Pancreatitis

The risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis is determined at least as much by the characteristics of the patient as by endoscopic techniques or maneuvers (Table 7.3). Patient-related predictors found to be significant in one or more major studies include younger age, indication of suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, history of previous post-ERCP pancreatitis, and absence of elevated serum bilirubin.2–9 Women may have increased risk, but it is difficult to sort out the contribution of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, a condition that occurs almost exclusively in women. In one meta-analysis, female gender was clearly a risk,10 and women account for a majority of cases of severe or fatal post-ERCP pancreatitis.2,11

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, most often suspected in women with postcholecystectomy abdominal pain, poses a formidable risk for pancreatitis after any kind of ERCP whether diagnostic, manometric, or therapeutic. Suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction independently triples the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis to about 10% to 30%. The reason for heightened susceptibility in these patients remains unknown. Contrary to widely held opinion that sphincter of Oddi manometry is the culprit, multivariate analyses show that empirical biliary sphincterotomy or even diagnostic ERCP has similarly high risk.3 With the widespread use of aspiration instead of conventional perfusion manometry catheters, the risk of manometry has probably been reduced to that of cannulation with any other ERCP accessory. Most previous studies linking manometry with risk have been from tertiary centers in which manometry is always performed in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, thus losing the ability to separate the contribution of risk from the procedure from that of the patient. Two studies specifically compared risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients having ERCP for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction with and without sphincter of Oddi manometry and found no detectable independent effect of manometry on risk.2,12 Absence of a stone in patients with suspected choledocholithiasis has been found to be a potent single risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients suspected of having stones, thus fitting into the category of possible sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. These observations point out the danger of performing diagnostic ERCP to look for bile duct stones in women with recurrent postcholecystectomy pain, as there is generally a low probability of finding stones in such patients and a high risk of causing pancreatitis. It is an erroneous and potentially dangerous assumption that merely avoiding sphincter of Oddi manometry will significantly reduce risk.

History of previous post-ERCP pancreatitis has been found to be a potent risk factor (odds ratio is 2.0 to 5.4)3,4 and warrants special caution. Advanced chronic pancreatitis, on the other hand, confers some immunity against post-ERCP pancreatitis, perhaps because of atrophy and decreased enzymatic activity.3 Pancreas divisum is only a risk factor if minor papilla cannulation is attempted.

Despite many early studies suggesting small bile duct diameter to be a risk factor for pancreatitis, most recent studies have shown no independent influence of duct size on risk; small duct diameter may have been a surrogate marker for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in the earlier studies using only univariate analysis. ERCP for removal of bile duct stones has been found to be relatively safe with respect to pancreatitis rates (<4%) in multicenter studies regardless of bile duct diameter.2 Neither the presence of periampullary diverticula nor Billroth II gastrectomy have been found to influence risk of pancreatitis.2

Technique-Related Risk Factors for Post-ERCP Pancreatitis

Technical factors have long been recognized to be important in causing post-ERCP pancreatitis. Papillary trauma induced by difficult cannulation has a negative effect that is independent of the number of pancreatic duct contrast injections, which is also a risk factor.2–10 Pancreatitis occurred in one study after 2.5% of ERCPs in which there was no pancreatic duct contrast injection at all.3 Acinarization of the pancreas, although undesirable, is probably less important than generally thought and has not been found to be significant in two recent studies.3,4

Overall, the risk of pancreatitis is generally similar for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP.2–10 Performance of biliary sphincterotomy does not appear to add significant independent risk of pancreatitis to ERCP,3,4 a finding that is contrary to widely held opinion. This is probably not due to the safety of sphincterotomy, but rather to the risk of diagnostic ERCP. Pancreatic sphincterotomy of any kind,3 including minor papilla sphincterotomy4 has been found to be a significant risk factor for pancreatitis, although the risk of severe pancreatitis has been very low (less than 1%), perhaps because nearly all of these patients had pancreatic drainage via a pancreatic stent.

Precut or access papillotomy to gain access to the common bile duct is controversial with respect to risk of pancreatitis and other adverse events. Use among endoscopists varies from less than 5% to as many as 30% of cases.13 There are many variations on precut technique: standard needle knife inserted at the papillary orifice and cutting upward; needle-knife “fistulotomy” starting the incision above the papillary orifice and then cutting either up or down; and use of a pull-type sphincterotome wedged either in the papillary orifice or into the pancreatic duct intentionally. Any of these techniques has the potential to lacerate and injure the pancreatic sphincter, and precut techniques have been uniformly associated with a higher risk of pancreatitis in multicenter studies involving endoscopists with varied experience, with precut sphincterotomy found significant as a univariate or multivariate risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis and/or overall adverse events.2,7 In contrast, many series from tertiary referral centers have found adverse event rates no different than for standard sphincterotomy, suggesting that risk of precut sphincterotomy is highly operator-dependent.14 In one study, endoscopists performing more than one sphincterotomy a week averaged 90% immediate bile duct access after precutting, versus only 50% for lower volume endoscopists, a success rate that hardly justifies the risk of adverse events.2

Comparative studies of precut with standard sphincterotomy are hard to interpret because indications and settings may be very different, with precut preferentially performed in lower risk situations such as obstructive jaundice and prominent papillae. In addition, increasing use of pancreatic stents in series from tertiary centers may have neutralized the otherwise higher risk of precut sphincterotomy.7 Adverse events of precut sphincterotomy vary with the indication for the procedure, occurring in as many as 30% of patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in older studies without use of pancreatic stents.2 Paradoxically, in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, needle-knife sphincterotomy over a pancreatic stent placed early in the procedure has been shown to be substantially safer than conventional pull-type sphincterotomy without a pancreatic stent.15

There has been controversy as to whether increased risk of precut sphincterotomy is due to the technique itself or due to prolonged cannulation attempts that often precede its use. A meta-analysis of six randomized trials with 966 subjects examined this issue.16 The meta-analysis included trials in which patients were assigned to early precut implementation or persistent attempts at standard cannulation. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was significantly less common in the precut group compared with the persistent attempts at cannulation group (3% versus 5%). However, the overall rate of adverse events including pancreatitis, bleeding, cholangitis, and perforation did not significantly differ (5% versus 6%). Hampering relevance of these studies is the fact that few of these studies included patients with high-risk indications such as sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, or involved use of pancreatic stents, which is now considered fairly standard.

Risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis escalates in patients with multiple risk factors.3 The interactive effect of multiple risk factors is reflected in the profile of patients developing severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. In one study predating widespread use of pancreatic stents, females with a normal serum bilirubin had a 5% risk of pancreatitis; with addition of difficult cannulation, the risk rose to 16%; with further addition of suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (i.e., no stone found), the risk rose to 42%.3 In two different studies, nearly all of the patients who developed severe pancreatitis were young to middle-aged women with recurrent abdominal pain, a normal serum bilirubin, and no biliary obstructive pathology.3,11 These observations emphasize the importance of tailoring the approach of ERCP to the individual patient.

One recent study has clearly shown that trainee participation adds independent risk of pancreatitis.4 In contrast, most multicenter studies have failed to show a significant correlation between endoscopists’ ERCP case volumes and pancreatitis rates.2,3,7 It is possible that none of the participating endoscopists in those studies reached the threshold volume of ERCP above which pancreatitis rates would diminish (perhaps >250–500 cases per year). However, most American endoscopists average less than two ERCPs per week,3 and the reported rates of pancreatitis from the highest volume tertiary referral centers in the United States are often relatively higher than those in private practices. All of these observations suggest that case mix is at least as important as expertise in determining risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree