Chapter 82 ABDOMINAL APPROACH FOR THE TREATMENT OF VESICOVAGINAL FISTULA

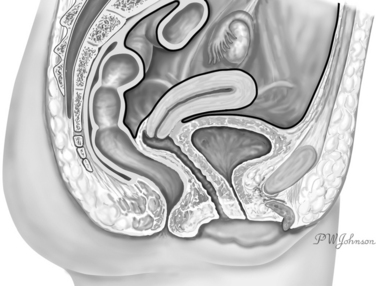

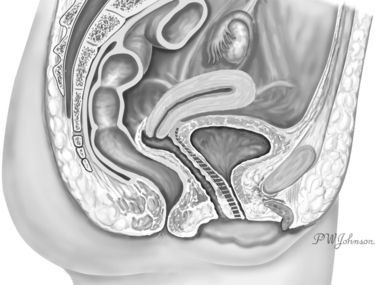

An abdominal approach can be used to repair a vesicovaginal fistula (VVF). A VVF, an abnormal communication between the bladder and the vagina, is located outside the abdomen. The peritoneum reflects over the bladder dome anteriorly and the lower third of the uterus posteriorly (Fig. 82-1). The lamina of connective tissue interposed between the bladder and the vagina, whose destruction is associated with the formation of the VVF (Fig. 82-2), is found well outside the abdominal cavity. From an anatomic perspective, it appears to be more intuitive and, indeed, to reach a VVF through the vaginal route instead of through the abdomen, specific technique for VVF repair originally was mastered by the vaginal approach. Nevertheless, the abdominal approach for treatment of the VVF has its own indications and can offer specific advantages over the vaginal route. The history of the development of this surgical technique can help us understand the part that the abdominal approach plays in VVF surgery.

HISTORY

The first surgeons who tried to correct a VVF did so through the vaginal approach. In 1663, Hendrik van Roonhuyse recommended transvaginal repair with the patient in the lithotomy position. Stiff swan quills were passed to the edges of the wound, and the bladder and surrounding tissues were widely mobilized. Van Roonhuyse’s book was published in 1676.1

The first two successful cases treated with this technique were reported by Johann Fatio in 1675.2 Despite these preliminary and isolated successful experiences, the presence of a VVF was commonly considered an incurable situation in the years that followed. An important innovation was introduced by Antoine Jobert the Lamballe in 1834, when he performed his first operation of transvaginal closure of a VVF by resection of the margins and coverage of the loss of substance with a cutaneous autograft obtained from the labia or the internal face of the thigh.3 The first operation was unsuccessful because of necrosis of the graft, but the patient was successfully cured on the second attempt with the same technique. Further developing the technique, Jobert pioneered later a method of tissue mobilization that widely detached the bladder from the vagina, which he called vesicovaginal autoplasty (autoplastie vesico-vaginale par glissement). He used this approach to avoid traction on the margins before suturing the edges of the fistula, and thereby obtained several successes in difficult VVF cases.4

In 1839, George Hayward5 reported the first cure of a VVF in the United States. He underscored the importance of accurate dissection of the vagina from the bladder before closing the fistula with stitches and pioneered the flap-splitting technique.5 In 1852, James Marion Sims6 published his first report of successful primary repair of a VVF, which was again performed transvaginally. This interesting paper has been recently republished in the medical literature.6 The correct surgical technique, the use of a new speculum designed by him, the search for the optimal patient position for exploration of the vagina, and an understanding of the importance of postoperative bladder drainage led to a high success rate for VVF treatment through the vaginal route and to international popularity for Sims.

This brief historical review shows that the basic principles stated by Sims and his predecessors for correct fistula treatment are still valid and that few modifications have been made by the surgeons who followed.7 However, in 1868, Thomas Addis Emmet, who succeeded Sims as chief surgeon of the Woman’s Hospital in New York, described some cases in which extensive scarring of the vagina and proximal location of the fistula compromised optimal access during transvaginal repair, indicating the need for higher access in these situations.8,9 Some years later, the abdominal approach for the treatment of VVF was introduced. The suprapubic transperitoneal-transvesical route was first described by Friedrich Trendelenburg in 1881,10 and in 1893, Von Dittel introduced the approach extraperitoned suprabubic for access to the VVF route.11 In 1902, Howard Kelly recommended a transperitoneal approach in the treatment of VVFs formed after hysterectomy that were too high in the bladder to be safely reached transvaginally.12 In 1914, Legueu13 described in more detail the transperitoneal-transvesical approach.13 To improve the chance of success in the most difficult cases, the omental graft technique was introduced by Hiltebrant in 1929 and further developed by Bastiaanse in the attempt to cure the challenging cases of postirradiation fistulas.14

In 1951, O’Conor and Sokol15 described the complete range of possible procedures for successful treatment of VVFs, from conservative measures to vaginal or suprapubic closure to urinary diversion.15 They emphasized the importance of careful selection of patients for each procedure. In some patients who had endured repeated previous failures, the fistulous opening was too high and too far from the bladder floor and the vagina too scarred to allow a vaginal approach. In these cases, a suprapubic procedure, preferably extraperitoneal, was described with bisection of the bladder down to the fistula opening and wide mobilization of the bladder from the vagina. A transperitoneal approach was selected when exposure was difficult because of previous operations, a history of cancer, or when the omentum needed to be used. With proper application of this technique, many successes were reported by O’Conor16,17 in the following years. However, the suprapubic approach was not used by O’Conor17 in 35% of his cases, for which a less invasive procedure was chosen.

ABDOMINAL APPROACH

Indications

An abdominal approach for the treatment of a VVF can be chosen for several reasons. Theoretically, the abdominal approach should be used when a less invasive approach is not feasible, but practically, this can have different meanings in different settings. At least four factors enter into the decision: the kind of fistula, the patient, the situation in which treatment takes place, and the surgeon. Fistulas are not all the same, and treatment must be individualized. Case selection is important.18,19 The abdominal approach was developed to treat fistulas that were too high or too far from the bladder floor to be reached transvaginally. Moreover, in some cases, especially after several previous attempts, the vagina can be severely scarred and cannot be used for access to the fistula. Application of this concept depends on the surgeon’s experience. Surgeons who have extensive experience with transvaginal surgery perform most repairs in this way, finding treatment of most fistulas amenable to the transvaginal approach.20,21 Even the most complex fistulas can be repaired with the use of a peritoneal flap.22

The treatment setting also can influence operative decisions. In some tropical countries, for example, general anesthesia is not commonly available, which makes widespread use of the abdominal approach almost impossible.23,24 In this situation, the technical level of hospitals encourages the use of less invasive procedures that can be performed safely under spinal anesthesia.25,26 The surgeons’ preferences are based on general surgical experience, familiarity with the procedure, and personal opinions about the case. Box 82-1 summarizes the indications for the abdominal approach that are consistently reported.

Timing

The best time to intervene and repair a fistula is unknown. Initially, treatment delay was advocated by some surgeons,16,27,28 but later data indicate that immediate treatment is beneficial.26 Treatment decisions are complicated by the fact that fistulas can be completely different pathologic entities, from the small, clear-cut opening produced during pelvic surgery, which is suitable for immediate repair,29 to the large, necrotic loss of substance, which results from hours of ischemic injury to the bladder during obstructed labor.30 Timing should be tailored to the specific situation.31,32

It seems reasonable that a fistula should be treated as soon after diagnosis as possible, with timing modified according to the individual case. In the developed world, there often is no reason to postpone treatment.29,31,33–35 Exceptions include the presence of infection or significant edema or a massive hematoma at the site of the fistula, which should be resolved before surgery. Taking care of coexistent problems usually requires not more than a few weeks, during which regular cystoscopic evaluation may be advisable.36

The possibility of spontaneous closure should be considered, especially for small, clean, postoperative fistulas, because spontaneous closure has been described in several cases after a trial of observation for 3 to 4 weeks.26,37–39 After a conservative trial is started, we avoid using an indwelling catheter during the period, to minimize local infection and edema.

Large fistulas, fistulas recurring after previous attempts at repair, multiple fistulas, or those associated with other conditions that require surgical treatment are not prone to spontaneous closure, and there is no reason to consider a conservative approach. These cases are more often treated with the abdominal approach. Box 82-2 addresses the suggested timing of VVF management.

Preoperative Preparation

The following guidelines for the preoperative preparation of the patient are based on published data and our personal opinions and experience. Preoperative preparation should not delay surgery, unless there is infection, massive hematoma, or significant edema at the site of the fistula (see Box 82-2). The performance status and nutritional status of some patients may require time for improvement. This situation may be more common in countries with a high incidence of VVF among poor patients. In these cases, preoperative preparation to improve the general condition of the patient is indicated, as emphasized in several reports.14,23,30,40 Box 82-3 summarizes the issues concerning preoperative preparation of VVF patients.

As soon as the patient is ready for surgery the issue of antibiotic prophylaxis must be considered. A randomized control trial, which reported the results for 79 VVF in 1998, showed that antibiotic prophylaxis (500 mg of ampicillin IV) at the start of the operation did not produce benefit in terms of success rates, but it seemed to reduce postoperative urinary infections and the need for long-term antibiotic therapy.41 Consistent with this first experience, in a large series from Nigeria Waaldjik, reported a success rate of 98% for 1716 cases of VVF without the use of antibiotic prophylaxis.26 Postoperative wound infection was not never seen, and antibiotic use does not seem to be mandatory according to these data. However, when economic restrains are not severe, antibiotic prophylaxis may be considered and continued postoperatively when necessary or in cases involving surgical manipulation of the intestines.

Another consideration is the use of cortisone. Collins and associates42 reported the use of oral corticosteroids (100 mg, three times daily for 10 to 12 days preoperatively) in the treatment of fistulas to reduce edema and fibrosis. Cortisone use is not widely accepted before surgery for VVF because it may compromise healing. It is difficult on the basis of the available data to justify the use of steroids before fistula repair.

Local application of estrogen creams has been advocated as a preoperative measure.17,43,44 Estrogens can improve the cellular proliferation rate and blood supply of the vaginal wall, which contains estrogen receptors in the epithelial layer. Estrogen receptors are also found in the connective tissue of the female pelvis between the bladder and the vagina. This tissue undergoes atrophy with hypoestrogenism. It therefore seems wise to recommend the local use of preoperative estrogen creams, particularly in postmenopausal or post-hysterectomy patients. Even in premenopausal women, the use of estrogen creams has helped in healing postcesarian VVFs soon after delivery.45 Consistently, the use of tamoxifen, an anti-estrogen drug, has been associated with poor local healing after gynecologic surgery.46 However, the epithelium that lines the fistulous tract itself contains estrogen and progesterone receptors in vesicouterine fistulas.47 Estrogen stimulation in this case could antagonize spontaneous closure of the fistula by maintaining the lining epithelium. Jozwik and Jozwik48 reported spontaneous closure of vesicouterine fistulas with hormonal suppression by induction of amenorrhea, supporting the role of estrogens in the maintenance of this kind of fistula. There are few data on the histology of VVFs. It is not known whether estrogen receptors are present in the epithelium lining VVFs. A case of persistent VVF associated with endometriosis has been reported,49 but endometriotic tissue was not found on histologic analysis of the fistula’s epithelium. In a few cases, estrogens may maintain the fistula’s epithelium, but this seems more common in vesicouterine fistulas and has never been demonstrated in VVFs.

Surgical Technique

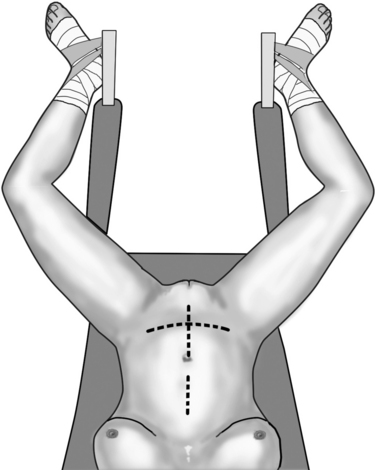

A catheter is placed in the bladder. The surgical instruments are those used during classic pelvic surgery. Autostatic retractors are useful. Laparotomy can be performed by a lower midline incision or by a Pfannenstiel incision, especially when a previous operation used this route (Fig. 82-3). When needed, both incisions can be extended to the upper abdomen to obtain access for omental preparation. The median incision is extended upward, and the Pfannenstiel incision can be integrated with an extra-short epigastric median incision. Sometimes, reaccessing a previous Pfannenstiel incision may not guarantee proper exposure of the pelvis. In this case, the suprapubic cross incision or a suprapubic V-shaped incision, as described by Turner-Warvick and Chapple50,51 and Turner-Warvick and coworkers52 can be a suitable choice. This is particularly valid when the patient previously had surgery by the Pfannenstiel route. An additional midline incision would leave this patient with a double-cross–like scar and a long-lasting memory of the VVF. The suprapubic cross incision allows reopening of the skin though the previous incision, but after dissecting the subcutaneous tissue away from the rectal fascia, it must be transected vertically on the midline up to the umbilicus, not along the previous horizontal fascial incision. The V-shaped incision is a variant, in which after a Pfannenstiel skin incision, the rectus sheath is opened upward and laterally toward the anterior superior iliac spine; distally, the fascial incision is truncated with a 4-cm horizontal tract at the level of the pubic symphysis.

Anterior Transvesical Approach

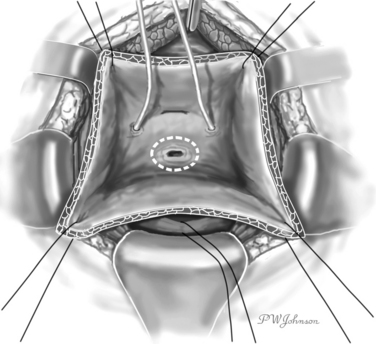

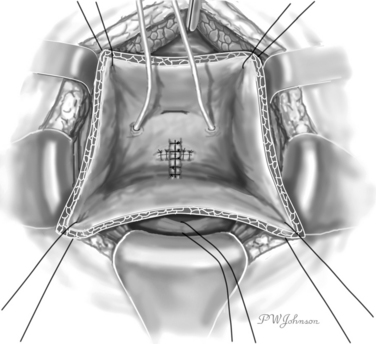

After the fascia is open, the Retzius space is entered. Dissection of the Retzius space allows preparation of the preperitoneal surface of the bladder, separating it from the surrounding structures. A self-retaining retractor can be placed at this point to keep the abdominal wall stabilized laterally. A vertical anterior cystotomy is performed, which allows visualization of the internal surface of the bladder with the fistula and the ureteral openings. If fistula and ureteral openings are close, ureteral catheters can be passed in the ureters at this point. A delicate retractor or suspension sutures can be used to separate the bladder walls (Fig. 82-4).

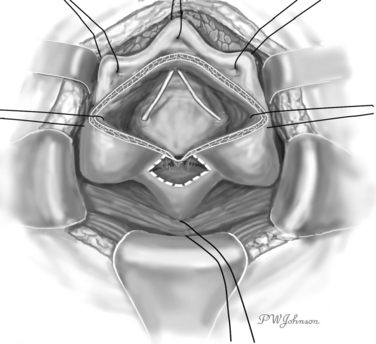

The operation proceeds with a racquet-shaped excision of the bladder wall around the fistula opening in the bladder and of the fistulous tract until clean, well-vascularized margins are obtained (Fig. 82-5). Some methods can help to gain traction on the fistula and facilitate its dissection, including use of a Foley catheter with an inflated balloon44 and specially designed devices passed through the fistula53,54 from the bladder opening to the vaginal opening. Dissection of the bladder from the vagina around the fistula is carried out to obtain free lateral margins, which can be then sutured without traction. Meticulous hemostasis is recommended during these maneuvers, with care taken to avoid ischemic damage to the tissue, which may compromise the repair.

At this stage, sutures are placed, starting deeply from the vaginal site. Interrupted, absorbable, 2-0 or 3-0 sutures are recommended. One layer is enough at the vaginal site. For fistulas located at the bladder neck, it may be feasible to close the vaginal end of the fistula from the vagina, using a combined abdominoperineal approach.55 The bladder end of the fistula is then closed with a double layer (muscular layer and mucosal layer) of interrupted or continuous sutures (see Fig. 82-5). Absorbable sutures should be used. The ureteral catheters are removed, and the anterior cystotomy can be closed in a similar double-layered fashion. A drain is left in the Retzius space, along with a suprapubic cystostomy or a transurethral catheter, or both. The catheter’s balloon is not inflated or inflated with only 4 to 5 mL to avoid balloon compression on the suture lines.

O’Conor Technique

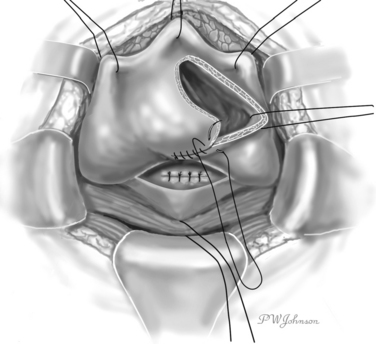

The O’Conor technique is based on complete bisection of the bladder and wide separation of it from the vagina. In its original description, it was performed extraperitoneally, but intraperitoneal access sometimes is required.15,16

The bladder is exposed extraperitoneally with as much dissection as necessary to free its posterior wall. The peritoneum can be opened when the extraperitoneal posterior exposure of the bladder is insufficient, when additional procedures or omental interposition is required, or when the patient has undergone previous operations for carcinoma.17

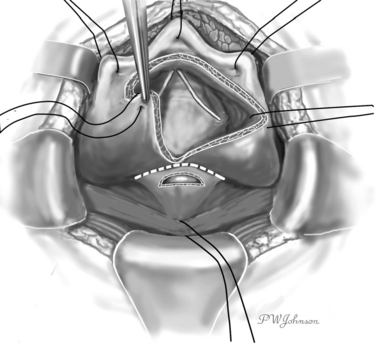

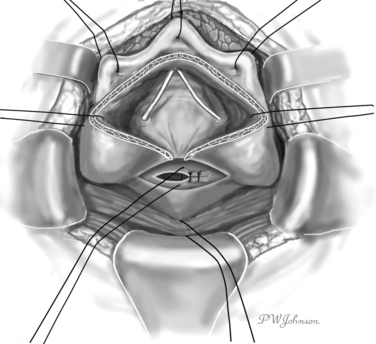

The interior surface of the bladder is inspected, and the ureters can be catheterized. The bladder wall around the fistula is sectioned circularly, and the fistula is excised to obtain free, healthy margins (Fig. 82-6). All necrotic and nonviable tissue is excised; a wide, lateral dissection of the bladder from the vagina is obtained; and the bladder is moved upward and anteriorly, with careful hemostasis to prevent postoperative ischemia (Fig. 82-7). The suturing begins at this point. Transverse vaginal closure is achieved with a single or double layer (double layer in the O’Conor’s description of the procedure15) of absorbable continuous or interrupted sutures (Fig. 82-8). Longitudinal bladder closure is then achieved with a double layer of absorbable interrupted or continuous sutures. The bladder closure starts from the distal apex of the cystotomy and walks upward (Fig. 82-9). Interposition tissue such as peritoneum or fat can be placed over the top of the vaginal suture to reinforce it. Unlike the original description, the vaginal site of the fistula is not always closed, because some surgeons think that closure can prevent drainage of hematomas from the widely dissected intervesicovaginal space.56 A drain is left in the retropubic space before closing the abdomen, along with a cystostomy or a transurethral catheter, or both.