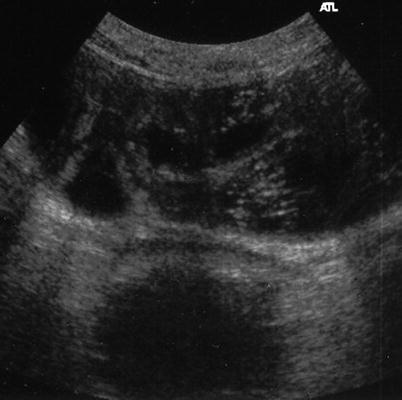

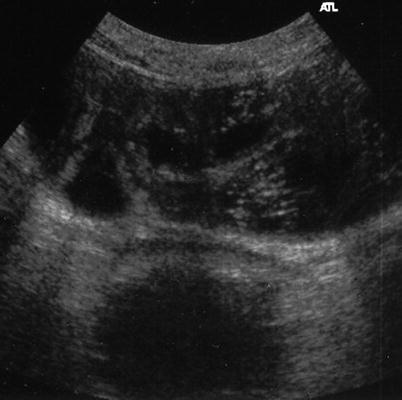

Fig. 1

a US images showing a dilated small bowel loop with increased mixed, mainly echogenic intraluminal fluid content and b diffuse bowel wall thickening with ascites a

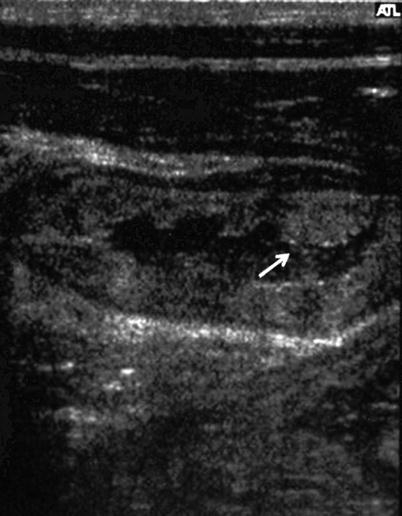

Fig. 2

US image showing a dilated small bowel loop with a thickened bowel wall with plical hypertrophy (arrow), and mesenteric edema

2 Whipple’s Disease

Whipple’s disease is a rare, multisystemic chronic infectious disease (approximate annual incidence less than 1 per 1,000,000 population) that preferentially affects middle-aged white men (Schneider et al. 2008).

Whipple’s disease is a chronic disorder characterized by diarrhea, weight loss, arthralgias and cardiac, and neurological involvement. It is caused by a small gram-positive bacillus, Tropheryma whippelii, a low-virulence but highly infectious action bacterium. The onset can be very insidious and is characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, steatorrhea, and abdominal pain, associated with migratory large joint arthropathy, fever, and ophthalmological and neurological manifestations (Bai et al. 2004).

Whipple’s disease most frequently occurs in middle-aged Caucasian men. Its diagnosis is suggested by the clinical findings, and confirmed by tissue sampling from the small intestine and/or other involved organs (lymph nodes, liver, central nervous system, etc.). The presence of PAS-positive (periodic acid Schiff stain) macrophages containing small bacilli, definitely supports the diagnosis. The treatment is based on a prolonged antibiotic course, with the first-choice regimen being the use of trymethoprim/sulphamethoxazole for 1 year, and the second choice chloramphenicol. PAS-positive bacilli can persist after successful treatment, and their presence outside macrophages is indicative of persistent infection. The recurrence of the disease, especially with dementia, carries an extremely poor prognosis and, in this case, the use of antibiotics crossing the blood–brain barrier can be very useful.

A number of reports on individual cases and a few case series have described the US abdominal findings, which can suggest the presence of the disease even if they are not very specific (Albano et al. 1984; Bruggemann et al. 1992; Carroccio et al. 1996; Castagnone et al. 1991). In particular, most of these studies have identified a moderately dilated and thickened small bowel wall, with the disappearance of normal bowel wall stratification and brilliant hyperechoic luminal contents mixed with a few hypoechogenic parts (Fig. 3), as well as an unusual, distinctive, and diffusely echogenic retroperitoneal lympadenopathy (Davis and Patel 1990), sometimes with concomitant free abdominal fluid or lymph node cavitation (Waziéres et al. 1993). It is interesting to note that the US abnormalities revert with an appropriate long-term antibiotic therapy.

Fig. 3

US image showing dilated and thickened small bowel loops with the disappearance of normal bowel wall stratification and brilliant, hyperechoic luminal contents

3 Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is an uncommon condition of unknown etiology, although it is generally believed to be due to intestinal allergy and affects both children and adults. Its clinical manifestations can be very heterogeneous and the disease may mimic peptic ulcer, subacute (or chronic) intestinal obstruction, gastroenteritis, irritable bowel syndrome, or inflammatory bowel disease.

It is characterized by a selective eosinophilic infiltration of the stomach and/or small intestine. The eosinophil eotaxin and Th-2 cytokines are important in the pathogenesis of the disease. It may be confused with parasitic and bacterial infections, inflammatory bowel disease, hypereosinophil syndrome, myeloprolipherative disorders, periarteritis, vasculitis, scleroderma, drug hypersentitivity, or injury (Oh and Chetty 2008).

Primary eosinophilic gastroenteritis include multiple disease entities depending on the level of histological involvement, and may be mucosal, muscular, or serosal (Lee et al. 1993).

The mucosal form (i.e. the most common variant) is characterized by vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, blood loss, iron deficiency anaemia, malabsorption, and protein-losing enteropathy. The muscular form is characterized by eosinophilic infiltration in the muscular layer leading to the thickening of the bowel wall which may cause bowel obstruction. The serological form occurs in only a minority of cases, and is characterized by exudative ascites and a higher peripheral eosinophil count than that associated with the other forms (Talley et al. 1990; Lee et al. 1993; Rothenberg 2004).

Diagnosis is often difficult, and most cases are only diagnosed after a surgical procedure and histological sampling. The withdrawal of the types of food being supposedly involved by means of skin prick testing (or RASTs Radio-Allergo-Sorbent Test) has variable effects. The treatment of choice is the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs, such as systemic or topical steroids. In those severe cases, when the dietary restriction fails, intravenous feeding or immunosuppressive antimetabolite therapy (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) should be considered (Talley et al. 1990).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree