1. Malignant diseases

a. Haematologic (Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, amyloidosis)

b. Metastatic (from numerous primary sites)

2. Immunological diseases

a. Crohn’s disease

b. Ulcerative colitis

d. Systemic lupus erythematosus

e. Primary sclerosing cholangitis

f. Sjögren’s syndrome

g. Primary biliary cirrhosis

3. Infectious diseases

a. Viral (EBV, CMV, viral hepatitis, herpes simplex, adenovirus, HIV)

b. Bacterial (Yersina paratuberculosis, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, brucellosis, tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infection)

c. Parasitic (toxoplasmosis, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, filariasis)

d. Chlamydial (lymphogranuloma venereum, trachoma)

e. Fungal (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis)

4. Other disorders

a. Lipid storage diseases (Gaucher’s, Niemann-Pick, Castleman’s disease)

b. Sarcoidosis

c. Familial Mediterranean fever

2 Normal Mesenteric Lymph Nodes

Regional mesenteric lymph nodes are usually detected as the result of a symptom-directed diagnostic work-up, by a variety of imaging techniques, including ultrasound and colour-Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When they are found, the main goal of the diagnostic technique is to suggest whether it is a normal finding or the sign of a past or ongoing abdominal disease, and in this context, to differentiate its benign from malignant nature.

The ultrasonographic criteria of the enlargement of mesenteric lymph nodes have been variably defined as the detection of nodes larger than 4 mm in the short axis (Sivit et al. 1993) and larger than 10 mm in the long axis (Watanabe et al. 1997). This sonographic definition is in agreement with that of a study based on CT studies in an adult population where mesenteric lymphadenitis has been defined as three or more lymph nodes, each 5 mm or greater than 5 mm in the short axis (Macari et al. 2002). However, this size might not be a reliable normal cut-off value in children where it is much more controversial. Karmazyn et al. (2005) showed that mesenteric lymph nodes with a short axis of greater than 5–10 mm are commonly found in children and should be considered a non-specific finding. In this population, a threshold of short axis at least 5 mm for enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes might yield a high percentage (54 %) of false-positive results. In contrast, if a short axis greater than 8 mm was used as a cutoff value, this would yield only a 5 % false-positive rate.

Therefore, the sonographic detection of oval, elongated, U-shaped lymph nodes with a short-axis diameter up to 4 mm in adults and 8 mm in children should be considered a normal finding and should not be misdiagnosed as an early manifestation of a lympho-proliferative disorder.

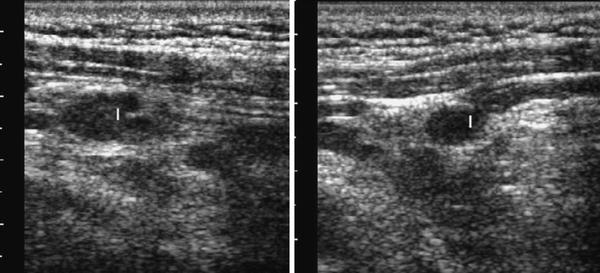

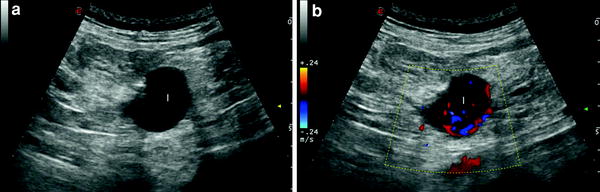

Normal mesenteric lymph nodes may be routinely identified at the mesenteric root and throughout the mesentery, in particular in right iliaca fossa in children (Karmazyn et al. 2005) and at the mesenteric root in adults (Lucey et al. 2005) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Ultrasonographic appearance of normal lymph nodes (l) as incidental findings in adult patients (a, b) and in a child with constipation (c)

Size, site and number of lymphadenopathy detected by abdominal ultrasound may help in suggesting their nature, or atleast in differentiating among their main causes that may be neoplastic, infectious or inflammatory.

3 Neoplastic Conditions

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy may result from metastatic malignancy. The ultrasonographic criteria used to differentiate between benign and malignant cervical nodes, may also be adopted to differentiate benign from malignant enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes. Shape, size and echogenicity can been considered for this purpose. Sonography can determine the long (L) axis, short (S) axis and a ratio of long to short axis. An L/S ratio of <2.0 (namely a round shape of the node) has a sensitivity and a specificity of 95 % for distinguishing benign and malignant nodes. This ratio has greater specificity and sensitivity than measurement of either the long or the short axis alone.

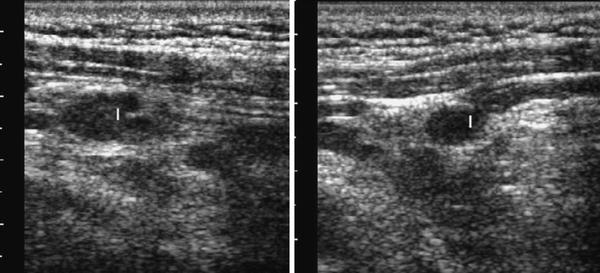

The most common malignancy resulting in mesenteric lymphadenopathy is lymphoma. While lymphoma usually presents as lymphadenopathy of the chest, retroperitoneum or superficial lymph node chains, it is not uncommon to also find mesenteric lymphadenopathy. Enlarged nodes may be seen at the mesenteric root and/or scattered throughout the peripheral mesentery. Early in the course of the disease, the lymph nodes may be small, soft and discrete (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Enlarged lymph nodes at mesenteric root, in a 52-year-old patient with early intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma

As the disease progresses, the enlarged nodes, often coalesce and tend to form a single mass (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Conglomerate abdominal mass formed by multiple coalescent lymph nodes (cm) (l: lymph node)

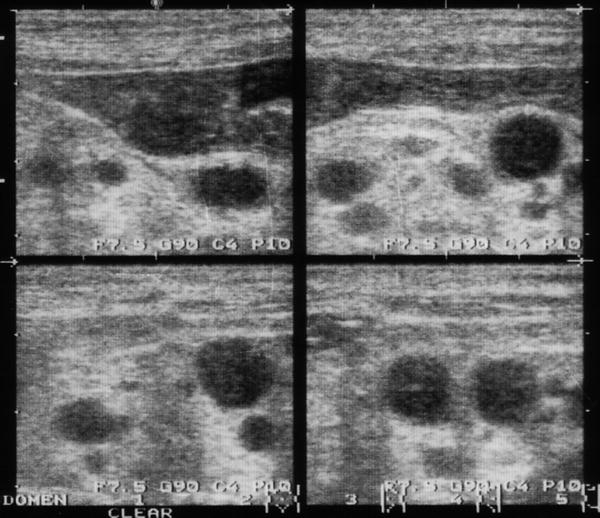

Extensive mesenteric lymphadenopathy due to lymphoma has a characteristic appearance. Mesenteric lymph nodes involved are usually hypoechoic, round and surrounded by hyperechoic mesenteric tissue (Fig. 4). The lymph nodes may also display a cystic appearance (Gorg et al. 1995, 1996a, b; Hollerweger et al. 2008).

Fig. 4

Typical mesenteric lymph node involvement in lymphoma, presenting as hypoechoic, round lesions surrounded by hyperechoic mesenteric tissue

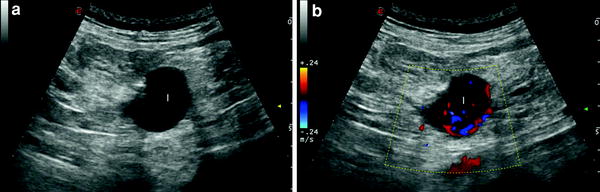

Use of power Doppler sonography or contrast-enhanced ultrasound (Sonovue 2.4 ml) to visualise the nodal vascularity can help in differentiating malignant from benign lymph nodes. Malignant nodes show more frequently avascular foci and aberrant and subcapsular vessels compared to benign lymph nodes which show a uniform vascular pattern confined to the hilar vessel only (Neumann-Silkow and Görg 2010; Fig. 5). However, power Doppler sonography or contrast-enhanced ultrasound are not able to correctly identify the specific malignancy and cannot replace US-guided fine needle aspiration, when feasible, or lymph node dissection (Hocke et al. 2008).

Fig. 5

a Ipo-anechoic round lymph node (l) at the mesenteric root, resembling a cyst at B-mode examination. b The study with colour Doppler ultrasound reveals aberrant and subcapsular vessels, suggesting the malignant nature of the node. After surgical node dissection, the final diagnosis was B-cell non Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Mesenteric lymph node involvement may be also associated with immune proliferative disorders of small intestine (Hermans et al. 2001; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6

Large hypoechoic lymph nodes (l) at the mesenteric root in a 43-year-old patient with immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID)

Primary malignancies that most commonly lead to mesenteric lymphadenopathy include carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract (in particular, carcinomas of the colon, duodenum and ileum), pancreas and less frequently of the lung, and carcinoid (Fig. 7). Most primary malignancies involve local lymph nodes before more distant metastases are detected.

Fig. 7

Regional metastatic lymph node (l) involvement in patients with gastro-intestinal cancer presenting as slight hypoechoic, soft and round lesion

4 Inflammatory Conditions

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy may be secondary to an underlying inflammatory process, either a localised inflammatory disease or a systemic inflammatory condition.

Local inflammatory causes, leading to mesenteric lymphadenopathy, are due to local mesenteric inflammation generally due to appendicitis, diverticulitis and cholecystitis.

Appendicitis is frequently associated with lymphadenopathy, most commonly in the mesentery of the right lower quadrant. Although lymph nodes may be identified in the mesentery of the right lower quadrant in the normal population, these are usually small and few in number. Multiple enlarged right lower quadrant lymph nodes, in the presence of an abnormal appendix, are useful in the diagnosis of appendicitis, although lymphadenopathy is not necessarily present to make the diagnosis.

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy may also be seen in cases of diverticulitis. The nodes are usually identified close to the area of inflamed colon, generally small but, unfortunately, not specific. In fact, diverticulitis may mimic perforated colonic carcinoma where adjacent enlarged lymph nodes may also be present.

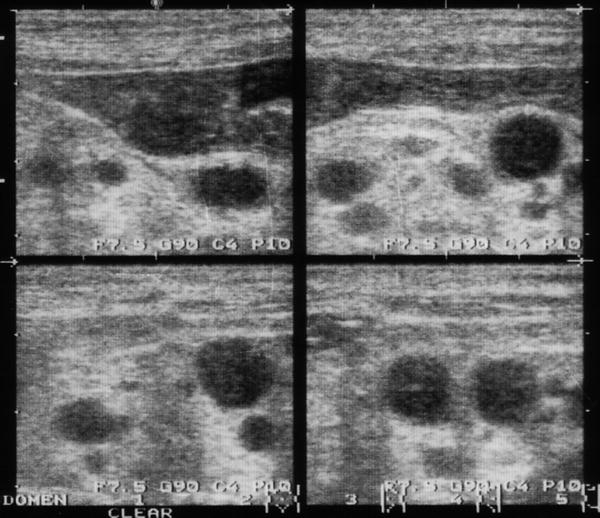

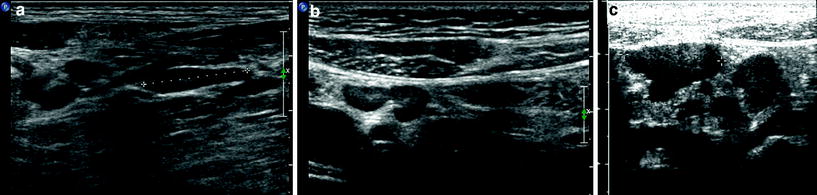

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy is commonly found in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (Maconi et al. 2005), although it is more common in Crohn’s disease. The lymph nodes may be found at the mesenteric root, mesenteric periphery or in the right lower quadrant (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy in a 40-year-old female with Crohn’s disease (a, b) and in a 28-year-old male with early ileal and jejunal Crohn’s disease (c). US images show multiple peri-intestinal lymphadenopathy in mesentery of right lower quadrant

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree