Chapter 79 URETHROVAGINAL FISTULA

Urethrovaginal fistula (UVF) presents a challenging diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma for the reconstructive surgeon. Because of its uncommon occurrence, much of what is known about this entity is derived from small series and case reports. Consequently, most UVFs are seen and treated in specialized centers, whether they manifest alone or in combination with a vesicovaginal fistula. The underlying cause, number of prior repairs, and damage to the continence mechanism are key factors in approaching the patient with a UVF. This chapter reviews the common causes, diagnostic modalities, and therapeutic options for UVFs.

ETIOLOGY

Postoperative Iatrogenic Factors

Traumatic fistulas resulting from obstetric deliveries account for most UVFs in underdeveloped nations, whereas in industrialized nations,1 UVFs occur as a complication of urethral diverticulectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, or other periurethral procedures. Some direct injuries are recognized at the time of the original surgery. In this instance, closure of the urethral lumen without verifying water-tightness, overlapping suture lines, lack of consideration for tissue interposition, insufficient bladder drainage, or a combination of these factors can contribute to the secondary formation of a UVF. Indirect mechanisms are less common but have been reported after periurethral collagen injection2 and an anterior colporrhaphy during which tight suburethral plication resulted in tissue necrosis and secondary fistula formation.3 An unrecognized urethral injury, which can occur during urethrolysis and particularly in the setting of dense periurethral scar tissue after a sling procedure, is another indirect mechanism. Most contemporary series on synthetic slings using tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tape report a low incidence of urethral injuries and secondary urethral erosions, which can result in UVFs.4–6

Other Causes

Vaginal lacerations after pelvic trauma, if ignored or inadequately repaired, can lead to UVF formation. Primary closure of vaginal lacerations is advocated to prevent fistula formation; regardless of the approach, these lacerations are susceptible to wound dehiscence if not properly débrided before repair.1 Although rare, a neoplasm arising from a urethral diverticulum7 can extend locally and manifest as a UVF. Likewise, radiation therapy for urethral cancer can lead to tumor necrosis and a secondary UVF.

DIAGNOSIS

Imaging

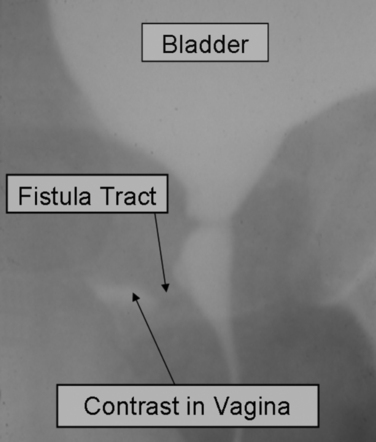

Visualization of the fistula tract may be accomplished by voiding cystourethrography8,9 or by double-balloon urethrography, but these techniques require high resolution to see the tract and true lateral views (Fig. 79-1). Upper tract imaging may be necessary for large or multiple fistulas to exclude ureteral obstruction or an associated ureterovaginal fistula. Urethral magnetic resonance imaging is of limited benefit to identify a fistula tract and is occasionally helpful in case of suspected residual diverticulum pocket associated with a UVF after urethral diverticulectomy.

Endoscopy

Direct visualization of the fistula opening on the floor of the urethral lumen with a short-beaked female urethroscope or a flexible scope can confirm the diagnosis.10 It is important to document the size of the opening and its location in the urethra in relation to the continence mechanism. The status of the bladder neck, trigone, and ureteric orifices should be observed, as well as the condition of the surrounding tissues for changes suggesting inflammation or neoplasm. A biopsy may be indicated for friable and irregular fistula edges or in case of a palpable induration around the fistula site. After vaginal laceration or urethral tear, the urethra may be completely strictured and the UVF located proximal to the site of urethral injury. Transvaginal endoscopy can help accessing the fistula tract and possibly the bladder by advancing a small flexible scope through the tract.

MANAGEMENT

Observation

Small fistulas in the distal urethra may be discovered incidentally and observed if minimally or asymptomatic. Spontaneous resolution of UVF with short-term catheter drainage has been reported.11 Most patients, however, choose surgical repair.

Surgical Repair

The goals of UVF repair are to close the tract, prevent recurrence of the fistula, and restore continence as indicated. In the case of a small distal fistula tract producing a split urinary stream with minimal or no incontinence, a simple marsupialization procedure to create a hypospadiac opening (i.e., Spence procedure) may correct the problem.12 We review two scenarios for transvaginal repair of a UVF, one involving a simple primary closure for a small nonirradiated UVF and the other a larger UVF necessitating more advanced techniques of urethral reconstruction and flap interposition for continence and closure.

Primary Closure with a Vaginal Flap

A primary repair using layered closure was first described by Collis,13 and it is ideal in the setting of a small to medium-sized UVF in nonirradiated tissues. Sterile urine must be obtained preoperatively, and antibiotic administration must be continued perioperatively. Several elements are necessary to facilitate a successful repair, as listed in Table 79-1. Patient positioning varies between advocates of the prone position14 and those preferring a high lithotomy position. Maximum perioperative urinary drainage is best achieved with a urethral and a suprapubic catheter. Exposure is facilitated by a Lonestar retractor (Lone Star Medi-cal Products, Stafford, TX) or other self-retaining retractor, a weighted vaginal speculum, a headlight, and even magnifying glasses if available. Passage of a Teflon guidewire over a 5-Fr open-ended ureteral catheter through the tract can facilitate the dissection of the tract (Fig. 79-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree