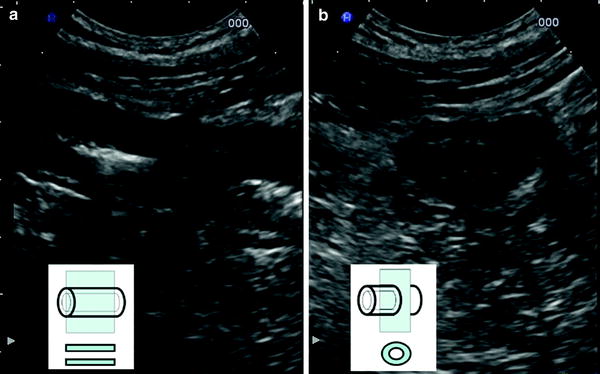

Fig. 1

Normal ileocecal anastomosis in a Crohn’s disease patient. Comparison of convex 3.5–5 MHz probe (a), fundamental imaging (FI) with high resolution 4–8 MHz microcovex probe (b) and tissue harmonic imaging (THI) with the same high resolution probe (c). Although the bowel wall is detectable in all these setting, using higher frequency and switching from FI to THI the delineation of outer contours of the bowel (arrows), the bowel wall echo pattern and mesenteric fat became much more delineated

For routine ambulatory examinations, it is preferable to perform the bowel ultrasound in a fasting condition. In fact, meal and feeding states may increase intraluminal gas and may hamper the evaluation of some abnormal functional features of the stomach, such as delayed gastric emptying. Also the intake of a large quantity of liquid meals and water just before bowel ultrasound should be avoided. In some instances, this may mimic partial small bowel obstruction (e.g. due to adhesions) and malabsorption (e.g. coeliac disease) hampering a correct diagnosis and the exclusion of these conditions. However, the fasting state is not mandatory (e.g. in acute abdomen, bowel ultrasound may be of value despite feeding condition).

Routine bowel evaluation of patients with chronic (or not acute) abdominal symptoms, usually should be systematically performed, e.g. starting from hypogastrium or left iliac fossa (i.e. from the sigmoid colon) and than continued to examine the colon, terminal ileum, appendix, small bowel, up to the stomach. However, other examination sequences may be valid provided the whole gut is assessed. On the contrary, in acute setting, in particular when a well-localised abdominal pain is present, bowel examination should start form the maximum tenderness area complained of by the patient, possibly with the help of the patient, who may put the probe just over the tenderness point. However, even in the acute setting, the bowel examination should assess all parts of the gastrointestinal tract.

In the event of suboptimal visualisation of the bowel wall due to the presence of gas, graded compression of the investigated gastrointestinal segment may help to shift intraluminal gas and thereby to improve visualisation of posterior parts of the bowel, in particular for the anatomical structures in the lower quadrants of the abdomen such as appendix, terminal ileum, caecum and sigmoid colon (Bluth et al. 1979). The patients are examined in supine position but, if necessary, they may be turned on the left or right side or put in an upright position, to move the bowel and its content, to avoid the interference of gas and optimise the visualisation of the features of bowel walls.

3 Normal Bowel Wall

The main features of the bowel walls to be assessed by ultrasound include: thickness, echo pattern, vascularity, flexibility and motility. These features depend in turn on the stretching and diameter of the hollow organs, which are associated with the content and presence of peristalsis that vary site-by-site in the gut. Probe frequency and grade of pressure wield by operators are other relevant parameters that may influence the ultrasonographic aspect of the gut.

Irrespective of the segment examined, as the gastrointestinal tract is a “tube”, ultrasound generally shows a “target” sign when the bowel segment is scanned transversally and as a “track” when it is scanned longitudinally (Fig. 2).

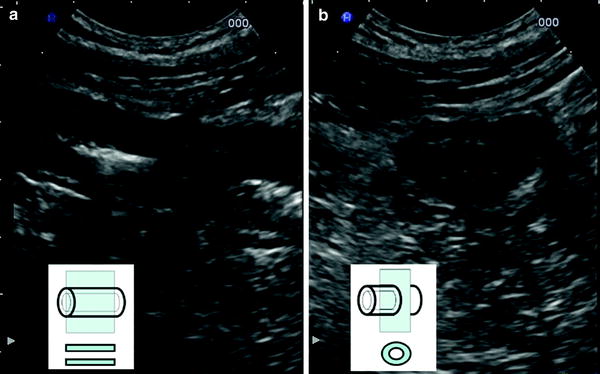

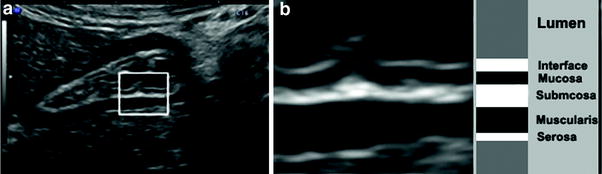

Fig. 2

Graphic representations and sonographic images of longitudinal (a) and transversal (b) sections of the terminal ileum in Crohn’s disease patient

3.1 Bowel Echo Pattern

Echo pattern and thickening are the most important features of the bowel wall, and those commonly considered to detect the diseases of the gut.

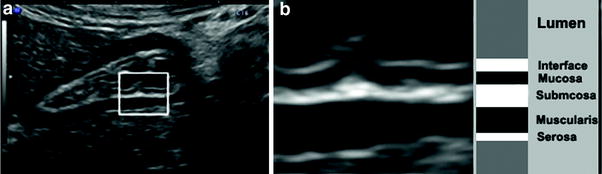

Under good conditions of visualisation, the ultrasographic aspect of the normal bowel wall is stratified, with five layers of different echogenicity. Each layer marks the boundary between two different histological structures. Starting from inside, the first layer is the interface between the lumen (hyperechoic) and the mucosa (tenuously hypoechoic). Between the mucosa and muscolaris propria (both hypoechoic) stands the submucosa (hyperechoic). The muscularis propria is limited by the last layer (hyperechoic), the serous (Fig. 3). Indeed, the wall layers and histology are not exactly matching, and the ultrasonographic image is not “the tissue” but rises from the resolution of different interfaces and reverberation artefacts (Bolondi et al. 1986; Kimmey et al. 1989; Nylund et al. 2008). However, their correspondence is used in the staging of some diseases and loss of stratification, when one or more layers are missing, is suspected or considered a sign of disease.

Fig. 3

Transversal section of gastric antrum (a) and detail of the normal wall (b) showing five layers, with different echogenicity

3.2 Bowel Thickness

The thickness of the bowel wall is regarded as the main ultrasonographic feature of the gut. Among the features of the bowel wall, this is the only quantitative parameter, and almost all studies reported only this value as the criterion to assess the presence of a gastrointestinal disease.

The measurement of wall thickness should be taken using the transducer with as high a frequency as possible, preferable 5 MHz or more or with the transducer that allows to distinguishing different layers of the wall. In fact, the measure of the thickening should be taken from the external hyperechoic layer, corresponding to the serosa, to the internal hyperechoic layer representing the interface between the mucosa and intestinal content. Only when these two interfaces are simultaneously visible in a perpendicular scan of the loop, the measurement should be considered appropriate. Since the dorsal part of the gastrointestinal tract is frequently difficult to image using transabdominal ultrasound, the measurements should be obtained from the anterior wall and repeated in that segment, both in longitudinal and transverse section, avoiding haustration and mucosal folds (e.g. in the colon; Fig. 4) and segments with spasms or contractions of the loop (e.g. in the small bowel and stomach; Fig. 5) to avoid overestimation of the thickness.

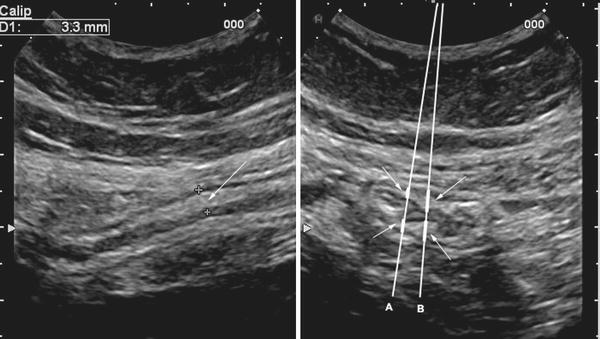

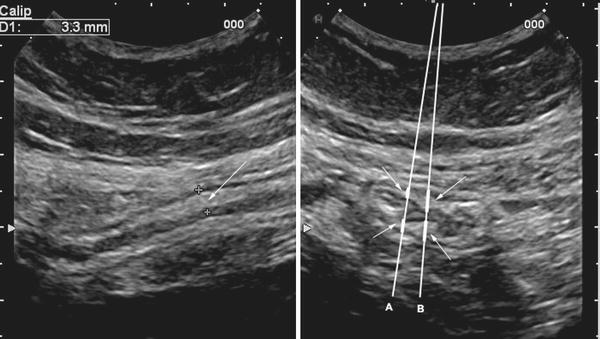

Fig. 4

Longitudinal (left side) and transverse (right side) sonographic section of the sigmoid colon in patient with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Because of the presence of mucosal folds, clearly appreciable of in the transverse section, the thickening of the bowel wall (arrows) in the lungitudinal section may vary according to the angle of insonation (A or B) of the loop

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree